Course:ETEC540/2009WT1/Assignments/ResearchProject/photocopier

The photocopier

History

In the thousands of years leading up to the invention of the printing press in 1454, copies of texts were predominately made by hand. For example, Monks would take months, and sometimes years, to duplicate a single text; this process was both tedious and prone to errors (Kendall, p. 222). The printing press made possible the ability to create exact and multiple copies of originals, however, it was still not possible to create a copy of an existing document (ibid, p. 222).

Following the invention of the printing press, copying machines were invented. In 1780 Watt created a machine that copied letters by pressing thin paper over handwritten text that had been written with special ink. This process created a reverse copy of the original. Because the paper was so thin, it could be turned over and read. Again this process, although much faster than scribing, was tedious and the resulting paper was very fragile. Today, letterpress copies are still found in archival research (Carlisle, p. 415). Other tools for copying included a stencil machine invented by Thomas Edison and the mimeograph invented by A. B. Dick in 1884 (ibid, p. 416).

A machine used to create multiple, good quality, paper copies of documents was not made until, in 1938, Xerography was invented by Chester F. Carlson, an American inventor/physicist and his assistant Otto Kornei, an Austrian physicist (Owen, p. 29). Carlson’s reason for inventing, what would later be known as the photocopier, was simple practicality. At the age of twenty-six, Carlson held a university degree in physics, but during the Great Depression in 1933, he was only able to retain work as a clerk for an electrical company (Kendall, p. 222). Similar to the physicist, Albert Einstein, Carlson worked with patents (Owens, p. 26) and made copies of technical diagrams and documents by hand. Carlson noted that, in order to create a copy of a drawing or blueprint, it “might be a wait of half a day or even twenty-four hours to get it back (Carlson in Owens, p. 26).” This not only cost the company time and money, it also involved a costly external company. Carlson recognized the need to create a machine “where you could bring a document to it, push it in a slot, push a button, and get a copy out (Carlson in Owens, p.24).”

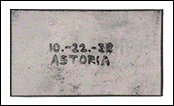

“The result was the biggest thing in imaging since the coming of photography itself (Owens, p. 27).” Xerography, the method discovered, involved “employing electrostatic charges, a dry powdered ink, and heat that would fuse the print and heat that would fuse the print onto paper (Carlisle, p. 416).” On October 22, 1938, Carlson and Kornei completed their first successful image transfer. Carlson wrote “10-22-38. Astoria” on a piece of paper and laid it on his Xerography machine. In less than a minute it produced a copy identical to the original. Carlson chose the name xerography because it stems from Greek words meaning dry writing (Kendall, p. 223).

In 1942 Carlson applied for a patent by providing diagrams and describing, in great detail, every aspect of xerography (Owens, p. 28). On October 6, 1942, Carlson, was given patent #2, 297, 691: electrophotography. Carlson's invention was “the first method of making images by dry copying (Hernandez, 2001).” However, it was not until 1944 that Carlson was able to garner interest in his invention when he signed a contract with a small science research firm, the Bauelle Memorial Institute in Columbus, Ohio (Kendall, p. 223). The institute licensed Carlson's copier to a small local photographic firm, named Haloid, that took an interest in Carlson’s product and, after making improvements, changed its corporate name to what has become synonymous with the photocopier, Xerox. The Xerox machine was invented in 1951 and a plain paper model was introduced in 1959 (Carlisle, p. 417, Owens, p. 30).

Impact in mainstream institutions

During the first decade after the Xerox machine was invented, over a half-million were sold. By 1969, Xerox copiers were making a staggering 75 billion copies a year (Kendall, p. 223, 224). Although the main purpose of the Xerox machine was to make copies, Fayard and Weeks conducted a study that revealed another effect that it has on the workplace. Their study involved the observation of a photocopy room used in a typical office environment. One of their principal findings was that the photocopy room was visited “by people at all levels of the organization (though some people spent much more time in the room than others) and at all times of the work day (Fayard & Weeks, p. 612)”

Furthermore because photocopying is a fairly routine and mundane task, it invites conversation to take place during its operation: “people would talk with whomever was using the photocopier as they entered the room to negotiate access to the machine or to use the fax machine or pick up office supplies from the cupboard there (Fayard & Weeks, p. 613).” People passing the room would also start a conversation with friends and colleagues using the machine as they passed by. Fayard and Weeks conclude by stating that “photocopier rooms afford informal interaction to the extent that they bring people into contact with each other (propinquity), allow people to control the boundaries of their conversation (privacy), and provide legitimate rationalizations for people to stay and talk to each other (social designation) (p. 626).”

Photocopiers, therefore, do not only provide a place to copy documents, they also provide an area in which colleagues can converse and consequently creates a more social work environment.

Cultural influence outside of non-institutional environments

Despite the incredible number of Xerox Machines that were sold in the 1960s, they also developed a use in non-institutional environments. Today, many small interest groups and grass roots movements gather interest for their cause by publishing a blog or creating a forum on the World Wide Web. In the 1970s, there was another movement in which individuals or small interest groups published what are known as zines: “self-published, low-budget publications produced predominantly by people between the ages of fifteen and thirty-five (Poletti, p. 85).”

Zines did exist before photocopiers, however, “the number of 'zines in circulation today is largely connected to the increasing availability of this technology [the photocopier] (Eichhorn, p. 122).” As well as increasing the circulation of zines, photocopiers were fast and relatively cheap. Furthermore, as the printing press enabled texts to be accessible to a much wider demographic, the photocopier provided a much more democratic method of distribution in that it “enabled writers to by-pass the authority invested in conventional printing processes (Eichhorn, p. 123).”

Consequently, in the 1970s and 1980s, the photocopier provided a medium through which non-professional publishers could write their opinions in public (Cox, 2000). This was especially popular in the late 1970s amongst Punk and Rock “fueled by the hostility of mainstream music magazines to the new music (Ginsberg and Savage in Wright, p. xliv).” Similar to the intellectual freedom that the Internet provides today, photocopiers did so (to a lesser extent) in the 1970s and 1980s.

Impact on Literacy and Education

Many changes that have occurred in education have not been due to educational research instead, they have been influenced by other factors (Shanahan & Neuman, p. 205). According to a U.S. Department of Education survey “84 percent of America's teachers consider only one type of information technology absolutely ‘essential' to their work - a photocopier with an adequate paper supply (Negroponte in Anson, 1999, p. 264).” Today, this opinion may have shifted towards a need for computers, but there is no doubt that photocopiers still play a huge role in education.

According to Abbott, print technologies, such as the “the spirit copier, then the ink duplicator and finally and most crucially the photocopier changed for good the relationship between teacher, text and technology (p. 4, 5).” Abbott believes that these changes are irreversible because teachers no longer depend on a single authoritative text to teach students. Instead, the photocopier gives them the opportunity to choose from a variety of different texts and “differentiate the learning activities they give to pupils in their care (Abbott, p. 5).”

Conclusion

The computer has, in many situations, replaced the photocopier. In a modern workplace, documents are likely to be created electronically and sent as an attachment and printed directly to a printer. Activist groups and grassroots organizations use the World Wide Web to voice their opinions and gather support. Educators are moving away from photocopying sections of texts for their students. Instead, they are teaching their students how to conduct their own research online. Universities are subscribing to online journals, e-books, government documents, and other digital collections. Consequently, university students do much of their research online.

However, the photocopier will continue to be used to create copies of documents, hand written notes, hand-drawn images and illustrations, magazines, newspapers, and books. Furthermore, the modern-day photocopier has evolved into a multipurpose machine that functions as a networked printer, a scanner, and a facsimile machine. Because of these innovations, the photocopier will continue to play a huge role in all of the above institutions.

References

Abbott, Chris. (2000). ICT: Changing Education. Routledge Falmer.

Anson, Chris, M. (1999). Distant voices: teaching and writing in a culture of technology. College English, 61 (3), 261 – 280.

Carlisle, Rodney (2004). Copy Machine. In Scientific American Inventions and Discoveries. (p. 415 – 416). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Cox, David. (2000, October 30). Notes on Culture Jamming. [Web log message]. Retrieved from http://sniggle.net/Manifesti/notes.php

Eichhorn, Kate. (1996). Cyborg grrrls: new technologies, identities, and community in the production of 'zines. (Masters thesis, B.A., Trent University, 1996). Retrieved October 25, 2009 from http://ir.lib.sfu.ca/bitstream/1892/8377/1/b18055540.pdf

Fayard, Anne-Laure & Weeks, John. Photocopiers and water-coolers: the affordances of informal interaction. Organization Studies, 28(05), 605 – 634.

Haven, Kendall (2006). Photocopier. In 100 Greatest Science Inventions of All Time. (p. 222 – 224). Libraries Unlimited. Place of Publication: Westport, CT. Publication.

Hernandez, Maria V. (2001, October 5). Patent for Xerox Technology Issued October 6, 1942. Retrieved October 25, 2009, from the United States Patent and Trademark Office website: http://www.uspto.gov/news/pr/2001/01-43.jsp

Owen, David (2004). Copies in Seconds. Simon & Schuster, Inc., New York.

Poletti, Anna. (2008). Auto/assemblage: reading the Zine. Biography, 31(1), 85 – 102.

Shanahan, Timothy & Neuman, Susan B. (1997). Conversations: Literacy Research That Makes a Difference. Reading Research Quarterly, 32(2), 202 – 210.

Wright, Frederick, A. (2001). From Zines to eZines: electronic publishing and the literary underground. (Doctoral dissertation, Kent State University, 1991). Retrieved October 28, 2009 from http://www.zinebook.com/resource/wrightdissertation.pdf