Course:EOSC311/2025/The Biological Relevance of Hydrothermal Vents

Hydrothermal vents are tectonically-associated cracks or holes on the seabed which produce jets of hot water, most frequently found near mid-ocean ridges or hotspots.[1] The water expelled from the vents carries with it plenty of elements and other nutrients, which support chemosynthetic organisms that reside by the vents. These organisms in turn support a community of larger organisms as the base of its food chain.[2] In addition to their role in supporting modern marine communities, hydrothermal vents are thought by some to have helped provide the conditions for the creation of life on Earth.[1] The idea is not without contention, however, as some scientists have expressed doubt over the ability of vents to support the creation of life.[3]

Statement of connection

I already knew that extremophiles lived by hydrothermal vents prior to taking this course, and the bridge between Geology and Biochemistry is very clear here, with a geological phenomenon directly responsible for supporting life. My initial goal was to lean more towards how extremophiles use the resources provided by hydrothermal vents to survive, but in researching the topic I learned about the hypothesis of hydrothermal-assisted abiogenesis. This greatly intrigued me, and I decided to shift the scope of this project to include the abiogenesis hypothesis. There is still a section on the extremophile microorganisms and the community they support, though, as those are also relevant connections between Geology and Biochemistry.

Hydrothermal Vents

Hydrothermal vents are cracks in the seafloor which expel jets of superheated water. They are formed in volcanically active areas, such as hotspots and mid-ocean ridges, when seawater gets deep into the crust by way of fissures on the seabed.[1][4] The water is then heated to high temperatures by the magma below, causing it to rise rapidly back to the surface and form a jet on the seabed. These jets of water can be as hot as 400 ℃, a stark contrast to the typical temperature of seawater around their depth, at roughly 2 ℃.[2] Due to the pressure at the bottom of the ocean being as high as 300 atmospheres, water ejected from hydrothermal vents is typically in liquid state. However, some vents are hot enough to surpass the critical point of seawater (407 ℃ at 298 bar),[5] causing ejected water to display traits of both liquids and gases.

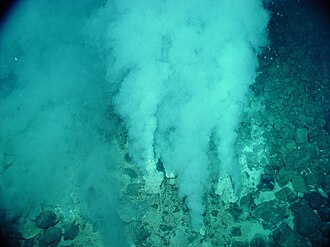

When seawater is heated deep within the crust, it dissolves minerals from the surrounding rock, which are then carried back to the surface as the water is expelled.[6] The minerals then precipitate when the geothermally-heated jet comes into contact with cold seawater at the surface, which can form chimney structures as high as 60 meters tall.[1] Precipitation of minerals also gives jets of water an opaque, cloudy appearance, and vents that produce cloudy jets are known as smokers. Smokers come in two categories, defined by the colour of the minerals they eject: black smokers, which are rich in metal sulfides such as the black-coloured iron sulfide, and white smokers, which are sulfate-rich and contain barium, calcium, and silicon.[1][4][6] In addition to their chemical differences, black and white smokers also differ in terms of temperature and pH. White smokers are generally more distant from their heat source than black smokers, and can be as cool as 40 ℃ whereas black smokers can be as hot as 400 ℃.[1] The pH difference between the two types of smoker is also quite large, with black smokers being very acidic at pH values as low as 2.8, while white smokers are basic with a pH above 9.[1][2]

Black smokers play an important role in supporting nearby life, with entire ecosystems capable of forming around a vent.[2] Extremophile bacteria can live in the hot, acidic environment around vents, and they make use of the expelled elements to produce energy in a process known as chemosynthesis. These bacteria make up the base of the food chain that supports plenty of larger organisms, such as octopi and tubeworms.[1][2] Bacteria can also contribute to hydrothermal vent communities as symbionts, living in the tissues of tubeworms and giant clams and providing them with organic nutrients.[2]

Hydrothermal vents have been suggested to have played a part in creating life on earth, with their unique environments potentially being suitable for the creation of organic molecules that are necessary for life as we know it.[1] Catalytic metals ejected by vents, as well as temperature, pH, and chemical gradients, have been proposed to aid in the creation of amino acids. Creation of amino acids has also been proposed to have occurred deep within the crust, with water bringing them up to the surface via hydrothermal vents.[7]

Hydrothermal Vent Ecosystems

Hydrothermal vents are much more biologically active than the rest of the ocean at their depth, where the lack of sunlight prevents photosynthetic organisms from surviving.[2] The elements and molecules expelled by hydrothermal vents provide an alternate energy source, allowing microbes to survive via chemosynthesis. Chemosynthesis is the creation of organic molecules from single-carbon molecules, using energy from the oxidation of inorganic materials or other single-carbon molecules.[8] Iron and Sulfur, two elements common in black smokers, are examples of nutrients used by chemosynthetic microbes, as are hydrogen gas and methane, which are also expelled by hydrothermal vents.[9] In addition to the production of organic compounds, some chemosynthetic organisms also fix nitrogen, providing another important service to hydrothermal vent communities.

The high temperature and low pH of black smokers make for typically uninhabitable conditions directly on the vents, but some organisms known as extremophiles are able to thrive there. Multiple species of chemosynthetic archaea live on the chimneys of black smokers, with their optimal living temperatures at around 100 ℃.[10] In addition to the heat, they are also adapted to living in acidic conditions and resistant to toxic molecules such as hydrogen sulfide. In order to survive in such harsh conditions, extremophiles have made a variety of adaptations. Extremophile proteins have unique structures and sequences that fare better under much higher temperature, acidity, and/or metal ion concentrations than normal, and hyperthermophilic archaea in particular have differences in DNA repair to better fight against heat-induced damage.[11][12]

The seafloor around a hydrothermal vent is dominated by mats of chemosynthetic bacteria.[2] These mats are the base of their community’s food chain, being eaten by amphipods and copepods, as well as larger animals such as limpets, clams, and mussels. Predators such as octopi feed on these bacteria-eaters in turn. A number of other organisms are also present in hydrothermal vent ecosystems, including fish, shrimp, crabs, and tubeworms. All of these animals are supported by chemosynthetic bacteria, but this isn’t all because of the bacteria’s role in the food chain. Hydrothermal vent ecosystems display a very high level of symbiosis, and the bacteria are often necessary to the host organism’s survival.[9] The environment around hydrothermal vents is very toxic due to the large amounts of sulfides and heavy metals produced by the vents, but organisms are protected from these toxins by chemosynthetic bacteria living in their gills.[13] The bacteria in return get greater access to their nutrients as they’re drawn through the gills.

Bacterial endosymbiosis also helps some organisms with their feeding.[2] Giant tubeworms receive the entirety of their nutrients from chemosynthetic bacteria living in their tissues, and they have no mouth, gut, or anus. Nutrients for the bacteria are absorbed into the tubeworm’s tissues. Tubeworms have a special adaptation in their hemoglobin that prevents sulfides from inhibiting the transport of oxygen, allowing them to uptake sulfides for their bacteria without suffering adverse effects themselves.[14] Tubeworms gain nutrients from endosymbiotic bacteria by farming them, allowing them to proliferate and then eating them.[15] Similar symbiotic relationships are found in other organisms in hydrothermal vent communities, such as giant clams and mussels.[2][15]

Hydrothermal Origin of Life Hypothesis

The conditions in hydrothermal vent environments are chemically suitable for the creation of organic molecules, suggesting that they may be able to support abiogenesis, the creation of life.[1] A hydrothermal origin of life was first proposed shortly after the discovery of black smokers, but has since turned to white smokers as the most likely source of hydrothermal abiogenesis.[16] An early proponent of the hydrothermal origin of life hypothesis was Günter Wächtershäuser, a chemist who also proposed the iron-sulfur world hypothesis, which would suggest that the iron sulfide-producing black smokers are responsible for abiogenesis, and supported the metabolism-first hypothesis, which states that a controllable energy-releasing cycle of chemical reactions occurred prior to the creation of genetic material.[17]

One important factor in the hydrothermal origin of life hypothesis is the existence of proton and electron gradients across the chimney walls of a hydrothermal vent.[16] Proton gradients could be a source of energy, much like they are in mitochondria, and electron gradients could aid in producing larger organic compounds from small molecules. A proton gradient could have formed due to the difference in pH between the slightly acidic seawater (pH 5-6) and the basic white smoker (pH 9-10), resulting in the outside of the chimney having a proton concentration roughly ten thousand times greater than the inside.[18] Black smokers could have proton gradients as well, although they would run in the reverse direction and wouldn’t be as powerful, as the most acidic black smokers have a pH of just below 3.[2] Both types of smoker can support an electron gradient, with hydrogen gas and methane on the inside of the chimney transferring electrons with carbon dioxide on the outside.[16]

Living organisms are composed of many complex organic molecules, such as proteins and nucleic acids, so the creation of such molecules must be possible for abiogenesis to occur. Aside from electron gradients, the minerals expelled by hydrothermal vents have been indicated to catalyze the creation of simple organic molecules from carbon dioxide dissolved in seawater.[19] Supercritical carbon dioxide, which has been found at some hydrothermal vents, is even more potent, capable of synthesizing amino acids with the presence of sufficient nitrogen.[20] It can also prevent hydrolysis and allow for dehydration synthesis of organic molecules, which are common issues with aquatic environments in the theoretical creation of life.[21]

While there are plenty of arguments in favour of the hydrothermal origin of life hypothesis, it is by no means the consensus agreement among scientists as the ultimate source of abiogenesis. Some have expressed doubt at some of the arguments, such as the ability of a proton gradient along chimney walls to have been a realistic source of energy.[22] Additionally, some people find terrestrial freshwater environments to be a more plausible place for abiogenesis, allowing for wet-dry cycles to aid in the formation of complex organic molecules.[3]

Conclusion

Hydrothermal vents are a great example of the intersection between Geology and Biochemistry. The chemosynthetic archaea and bacteria that live by hydrothermal vents allow for an ecosystem to thrive solely because of a tectonic phenomenon, and it’s difficult to find more of a direct connection than that. However, there is one: abiogenesis, also related to hydrothermal vents. I’m very pleased with the topic I chose for this project, as I think the relevance is very strong and researching it was very interesting, having learned about the hydrothermal origin of life hypothesis while doing so.

The origin of life is a contentious topic, as there are competing explanations as to both how and where life began. I found the supercritical carbon dioxide argument to be pretty convincing, as well as the idea that the minerals expelled by the vents could act as catalysts. I’m not as convinced by the proton and electron gradient arguments, as although they are not my area of expertise, they seem held together by a bit of wishful thinking, being reliant upon a tower of precipitates to act as a membrane and the cross-membrane interactions to be turned into something useful. I did not do much research on other potential locations of abiogenesis such as terrestrial freshwater pools, so I can’t comment on whether I find that to be more believable than hydrothermal vents.

The hydrothermal origin of life hypothesis is heavily aligned with the metabolism-first hypothesis, which states that cycles of energy-producing reactions occurred before genetic material. While this is the first time I’ve heard about the metabolism-first hypothesis, I’ve learned about a competing view in prior classes before, the RNA world hypothesis. The RNA world hypothesis states that self-replicating genetic material was the first step in early life. While the RNA world hypothesis may not be incompatible with hydrothermal abiogenesis,[18] it’s certainly less favoured than metabolism-first. As far as choosing between the two hypotheses goes, I think I’ll have to abstain here as well. It would take far more research than what I’ve learned about either hypothesis to form a well-thought-out opinion, and even then it’s a debated subject among well-established scientists.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 Colín-García, M., Heredia, A., Cordero, G., Camprubí, A., Negrón-Mendoza, A., Ortega-Gutiérrez, F., Beraldi, H., & Ramos-Bernal, S. (2016). Hydrothermal vents and prebiotic chemistry: a review. Boletín de La Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, 68(3), 599–620. https://doi.org/10.18268/bsgm2016v68n3a13

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 Botos, S. (2015). Hydrothermal Vent Communities. Retrieved from https://www.botos.com/marine/vents01.html

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Damer, B. & Deamer, D. (2020). The Hot Spring Hypothesis for an Origin of Life. Astrobiology. 20(4), 429–452. https://doi.org/10.1089/ast.2019.2045

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 NOAA. (2024). What is a hydrothermal vent? National Ocean Service website, https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/eutrophication.html

- ↑ Koschinsky, A (2008). Hydrothermal venting at pressure-temperature conditions above the critical point of seawater, 5°S on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Geology. 36(8). https://doi.org/10.1130/G24726A.1

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Cowan, A. (2023). Deep Sea Hydrothermal Vents. Retrieved from https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/deep-sea-hydrothermal-vents/

- ↑ Tunnicliffe, V. (1991). The Biology of Hydrothermal Vents: Ecology and Evolution. Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review. 29. 319–408.

- ↑ Enrich-Prast, A., Bastviken, D., & Krill, P. (2009). Chemosynthesis. Encyclopedia of Inland Waters, 211–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012370626-3.00126-5

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Jannasch, H. & Mottl, M. (1985). Geomicrobiology of deep-sea hydrothermal vents. Science. 229(4715), 717–725. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.229.4715.717

- ↑ Smithsonian Ocean Team. (2018). The Microbes That Keep Hydrothermal Vents Pumping. Retrieved from https://ocean.si.edu/ecosystems/deep-sea/microbes-keep-hydrothermal-vents-pumping

- ↑ Kumar, A., Alam, A., Tripathi, D., Rani, M., Khatoon, H., Pandey, S., Ehtesham, N. Z., & Hasnain, S. E. (2018). Protein adaptations in extremophiles: An insight into extremophilic connection of mycobacterial proteome. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology, 84, 147–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcdb.2018.01.003

- ↑ Grogan, D. (2015). Understanding DNA Repair in Hyperthermophilic Archaea: Persistent Gaps and Other Reasons to Focus on the Fork. Archaea. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/942605

- ↑ Kadar, E., Costa, V., Santos, R., & Powell, J. (2006). Tissue partitioning of micro-essential metals in the vent bivalve Bathymodiolus azoricus and associated organisms (endosymbiont bacteria and a parasite polychaete) from geochemically distinct vents of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Journal of sea research. 56(1), 45-52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seares.2006.01.002

- ↑ Flores, J., Fisher, C., Carney, S., Green, B., Freytag, J., Schaeffer, S., & Royer, W. (2005). Sulfide binding is mediated by zinc ions discovered in the crystal structure of a hydrothermal vent tubeworm hemoglobin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 102(8), 2713–2718. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0407455102

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Sogin, E., Leisch, N., & Dubilier, N. (2020). Chemosynthetic symbioses. Current Biology. 30(19), R1137–R1142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.07.050

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 New Study Outlines “Water World” Theory of Life’s Origins. (2014). NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/new-study-outlines-water-world-theory-of-lifes-origins/

- ↑ Wächtershäuser, G. (1990). Evolution of the first metabolic cycles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 87(1), 200–204. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.87.1.200

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Martin, W., Baross, J., Kelley, D., & Russell, M. (2008). Hydrothermal vents and the origin of life. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 6(11), 805–814. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro1991

- ↑ Roldan, A., Hollingsworth, N., Roffey, A., Islam, H., Goodall, J., Catlow, C., Darr, J., Bras, W., Sankar, G., Holt, K., Hogartha, G., & de Leeuw, N. (2015). Bio-inspired CO2 conversion by iron sulfide catalysts under sustainable conditions. Chemical Communications. 51(35), 7501–7504. https://doi.org/10.1039/C5CC02078F

- ↑ Shibuya, T. & Takai, K. (2022). Liquid and supercritical CO2 as an organic solvent in Hadean seafloor hydrothermal systems: implications for prebiotic chemical evolution. Progress in Earth and Planetary Science. 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40645-022-00510-6

- ↑ Deal, A., Rapf, R., & Vaida, V. (2021). Water–Air Interfaces as Environments to Address the Water Paradox in Prebiotic Chemistry: A Physical Chemistry Perspective. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 125(23), 4929–4942. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpca.1c02864

- ↑ Jackson, J. (2016). Natural pH Gradients in Hydrothermal Alkali Vents Were Unlikely to Have Played a Role in the Origin of Life. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 83(1-2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00239-016-9756-6

| This Earth Science resource was created by Course:EOSC311. |