Course:EOSC311/2023/Minsu's Term Project - Geology and My Major

Statement of connection and why you chose it

Module 2: 'What's in my cell phone?', focusing explicitly on essential geological resources and the locations of their main producers, directly relates to my major: Interdisciplinary Studies in Economics and Political Science. Within this module, the sub-module on Metalliferous Mineral Resources, particularly Mineral Resources and Mineral Reserves, aligns perfectly with my academic interests.

Political and economic relationships

In today's interconnected and resource-driven world, the significance of metalliferous mineral resources cannot be overstated. Among these resources, neodymium, one of REE (the rare-earth elements), holds a pivotal role due to its various applications in cutting-edge technologies such as electric vehicles, renewable energy systems, electronic devices, and advanced manufacturing. As a student pursuing a major in economics and political sciences, I am deeply intrigued by the intricate linkages between mineral resources, particularly neodymium, and the realms of economics and political sciences. This project aims to explore the multifaceted connection between metalliferous mineral resources, neodymium in particular, and its implications for economic systems, political landscapes, and international relations.

REE (rare-earth elements)

What is REE (rare earth elements)?

Rare earth elements (REE) consist of a set of 15 elements (lanthanum (La), cerium (Ce), praseodymium (Pr), neodymium (Nd), promethium (Pm), samarium (Sm), europium (Eu), gadolinium (Gd), terbium (Tb), dysprosium (Dy), holmium (Ho), erbium (Er), thulium (Tm), ytterbium (Yb) and lutetium (Lu)) known as the lanthanide series, which are positioned alongside scandium (Sc) and yttrium (Y) on the periodic table of elements.[1] REEs are key components in many electronic devices that we use in our daily lives, as well as in a variety of industrial applications. Over 200 products across various applications, particularly in high-tech consumer goods, including cellular telephones, computer hard drives, electric and hybrid vehicles, and flat-screen monitors and televisions, have rare-earth elements. Moreover, rare earth elements have a significant role in defense, encompassing electronic displays, guidance systems, lasers, radar systems, and sonar systems.[2]

| Rare Earth Element | Use | Rare Earth Element | Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lanthanum (La) | Catalysts, lighters, lamps, optics, alloys | Holmium (Ho) | Magnetic fields, lasers, colorant |

| Cerium (Ce) | Alloys, polishing, colorant, catalyst, lighters, turbine blade coating | Erbium (Er) | Laser surgery, fiber optics |

| Praseodymium (Pr) | Magnets, colorant, lasers, flints | Dysprosium (Dy) | Lasers, nuclear reactors, magnets, computers |

| Neodymium (Nd) | Lasers, magnets, computers, electric motors, generators, lighting, alloys | Thulium (Tm) | X-ray technology, lasers |

| Promethium (Pm) | Paints, nuclear batteries | Ytterbium (Yb) | Lasers, nuclear medicine, seismology, alloys |

| Samarium (Sm) | Magnets, lasers, nuclear reactor control rods | Lutetium (Lu) | Catalysts, positron emission tomography (PET) |

| Europium (Eu) | TV screens, nuclear reactors, lasers, fluorescent lamps | Scandium (Sc) | Aerospace alloys, light bulbs |

| Gadolinium (Gd) | Neutron shielding, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), lasers, computers | Yttrium (Y) | Lasers, TVs, superconductors, LEDs, light bulbs, cancer treatment |

| Terbium (Tb) | Magnets, lasers, fluorescent lamps, alloys, sonar technology, fuel cells |

Table 1: Uses of Rare Earth Elements, (Virginia Department of Energy, n.d.)[3]

How are rare earth elements formed?

Rare-earth elements can originate from volcanic activity, but a significant number of them were initially synthesized during supernova explosions that occurred in the early stages of the universe, predating the existence of Earth.[4]

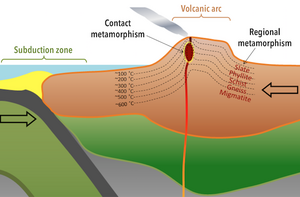

Most rare earth elements are found on two major mined minerals: Bastnasite and Monazite.[5] Bastnasite is found in the contact metamorphic zones, a form of metamorphism that takes place in the vicinity of intrusive igneous rocks, as a consequence of elevated temperatures caused by the intrusion of hot magma into the surrounding rock.[6] Monazite is a type of accessory mineral that can be found in igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary rocks. Furthermore, Monazite is distributed worldwide, including in placer deposits and beach sands.[7]

Features of Bastnasite and Monazite

Bastnasite occurs in three varieties, namely bastnasite-Ce, bastnasite-La, and bastnasite-Y. The distinguishing suffixes signify the predominant rare earth element found in each type. Bastnasite predominantly contains lighter rare earth elements compared to Monazite. Also, Bastnasite is generally preferred as the primary source of rare earth elements due to the radioactive nature of Monazite. Proper management of the radioactive by-products generated during monazite processing is a significant concern that needs to be addressed.[8]

Monazite exists in four primary variations: monazite-Ce, monazite-La, monazite-Nd, and monazite-Sm. Monazite can also contain thorium, which imparts a radioactive quality to it. This mineral is relatively uncommon and is typically found as an accessory mineral in specific granitic rocks and pegmatite veins. However, it is more commonly concentrated in streams and beach sands. Unlike Bastnasite, Monazite encompasses a broad spectrum of rare earth elements, ranging from lighter to heavier ones.[8]

Where can we get rare earth elements? (Reserves and Production)

According to the U.S. Geological Survey’s latest report on rare earths[9], China tops the list for reserves and mine production. While the U.S. has 2.3 million tons in reserves, it still depends on China for refined rare earths. Also, Vietnam has the second most reserves, aiming to increase rare earths production for clean energy. Brazil, Russia, India, Australia, the United States, and Greenland also have notable rare earth reserves. These countries are exploring various strategies to strengthen their rare earth sectors and enhance their role in the global supply chain.

| Country | Reserves | Country | Reserves | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | 44,000,000 | Australia | 4,200,000 | |

| Vietnam | 22,000,000 | Greenland | 1,500,000 | |

| Russia | 21,000,000 | Tanzania | 890,000 | |

| Brazil | 21,000,000 | Canada | 830,000 | |

| India | 6,900,000 | South Africa | 790,000 | |

| United States | 2,300,000 | Other countries | 280,000 |

Chart 1: Rare Earth Reserves (in MT) Highest to Lowest, (US Geological Survey, 2023)[9]

These are more information about reserves and production[10]

- China: China holds the highest reserves of rare earth minerals globally, with 44 million MT. It was the top producer in 2022, with an output of 210,000 MT. China has implemented measures to maintain and increase reserves while improving regulation and supervision.

- Vietnam: Vietnam has reserves of 22 million MT and experienced a significant increase in rare earths production from 400 MT in 2021 to 4,300 MT in 2022. The country is focused on expanding its clean energy capacity and has signed agreements with South Korea and Canada to strengthen cooperation on rare earths.

- Brazil and Russia: Both Brazil and Russia have reserves of 21 million MT. Brazil's rare earths production was minimal at 80 MT in 2022, while Russia produced 2,600 MT. Russia aims to invest in the industry to compete with China, but concerns arise due to its invasion of Ukraine.

- India: India holds reserves of 6.9 million MT and produced 2,900 MT in 2022. The country benefits from the significant beach and sand mineral deposits, serving as important sources of rare earths.

- Australia: Australia, the third-largest rare earths-mining country in 2022 with 18,000 MT of production, has reserves of 4.2 million MT. Lynas Rare Earths is the largest non-Chinese rare earths supplier.

- United States: The US reported the second-highest rare earths output in 2022, reaching 43,000 MT. It holds reserves of 2.3 million MT and has taken steps to review and secure domestic supply chains for rare earths.

- Greenland: Greenland possesses reserves of 1.5 million MT but has faced challenges in bringing them into production. The government canceled a rare earths-mining project, and the company's request for interim orders was declined.

Neodymium

What is Neodymium?

Neodymium, classified as one of the rare-earth elements, is a shiny silvery-yellow metal. It exhibits high reactivity and readily tarnishes in the presence of air, with the resulting protective coating unable to prevent further oxidation. Neodymium ranks as the second most abundant rare-earth element and is nearly as plentiful as copper. It is present in minerals containing all lanthanide minerals, such as monazite and bastnasite. Major neodymium-producing regions include Brazil, China, the USA, India, Sri Lanka, and Australia. Neodymium reserves are estimated to be around 8 million tonnes, and the global production of neodymium oxide amounts to approximately 7,000 tonnes annually.[11]

Why is Neodymium a matter?

The production of permanent magnets stands out as the primary and most significant utilization of rare earth elements (REEs), constituting 43% of the total demand in 2021. Permanent magnets hold a crucial position as indispensable components within modern electronic devices, including cell phones, televisions, computers, automobiles, wind turbines, jet aircraft, and various other consumer goods and industrial applications.[12] Samarium Cobalt (SmCo) magnets and Neodymium Iron Boron (NdFeB) magnets are significant rare earth permanent magnets. However, Neodymium Iron Boron magnets have a significantly stronger magnetic field, boasting the highest BH Max (maximum energy product) among all currently available permanent magnets. Additionally, NdFeB magnets are more cost-effective than SmCo magnets.[13] Based on these economic and scientific reasons, Neodymium is one of the most important rare earth elements now.

Neodymium in Economy

Economic importance of Neodymium

Neodymium is quite common and abundant, as mentioned above. However, Neodymium holds substantial economic significance as it finds extensive use in various industries and applications. Its primary role lies in the production of high-strength magnets called Neodymium Iron Boron (NdFeB) magnets, which are essential components in numerous sectors. Specifically, Neodymium magnets are integral to the functioning of electric motors, making them crucial in industries like electric vehicles, wind turbines, consumer electronics, medical equipment, and defense/aerospace. These Neodymium Iron Boron (NdFeB) magnets enable efficient power generation, enhance device performance, and support technological advancements.[12]

1. Electric Vehicles (EVs) and Renewable Energy: The increasing global demand for electric vehicles has significantly boosted the need for neodymium magnets. These magnets provide the necessary power and efficiency for electric motor systems, making Neodymium a critical element in the automotive industry's transition toward sustainable mobility. Also, Neodymium magnets play a pivotal role in the renewable energy sector, particularly in wind turbines. Their utilization of generators enhances power generation and expands wind energy capacity worldwide. Neodymium's presence facilitates the economic growth of the renewable energy industry.[14]

2. Consumer Electronics and Medical Equipment: Neodymium magnets are widely used in consumer electronic devices, including headphones, speakers, hard disk drives, and smartphones. Their compact size, lightweight nature, and strong magnetic properties improve device performance, ensuring superior sound quality and enhancing user experience. These features drive their economic importance in the consumer electronics market. Furthermore, Neodymium magnets find applications in various medical devices, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machines, magnetic therapy devices, and research equipment. These magnets deliver precise imaging and diagnosis capabilities, supporting advancements in medical technology and contributing to the growth of the healthcare industry.[15]

Overall, Neodymium's economic significance stems from its diverse applications across industries. Its utilization drives technological innovation and economic growth in electric mobility, renewable energy, consumer electronics, and healthcare sectors. Not even for the usage of alloy magnets, moreover, but also the process of making this strong and economical magnet can be the reason for the economic importance of Neodymium, which is job creation and economic growth. For example, the production, processing, and utilization of neodymium magnets create employment opportunities across the value chain, from mining and manufacturing to research and development. This fosters economic growth in countries involved in neodymium production and contributes to local and national economies.

Current Demand and Supply of Neodymium in the Market

More than 90% of EVs use brushless DC (BLDC) motors, which are made up of rare earth: Neodymium Iron Boron (Nd-Fe-B) magnets. As mentioned above, Neodymium is not solely used in the industry. It is used as the alloy, the Neodymium Iron Boron (NdFeB) magnets, which is mandatory for EV cars. During the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference, major countries and automakers agreed to a new goal of achieving full electrification by 2040. This declaration includes commitments from numerous nations to transition to zero-emission vehicles. The aim is for all new car and van sales to be zero-emission globally by 2040, with leading markets targeting 2035 as the deadline. Participating nations include Austria, Azerbaijan, Cambodia, Canada, Cape Verde, Chile, Croatia, Cyprus, Denmark, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Finland, Ghana, Kenya, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Mexico, Morocco, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Paraguay, Poland, Rwanda, Slovenia, Sweden, Turkey, United Kingdom, and Uruguay.[16]

There is a direct correlation between the EV market and the use of Neodymium in the automotive industry. The increasing demand for electric vehicles (EVs) is a driving factor behind the growing use of Neodymium since Neodymium magnets are essential components in the motors of electric vehicles since they provide the necessary power and efficiency for the electric motor, contributing to the overall performance and range of the EV. As the adoption of electric vehicles continues to rise, the demand for Neodymium is also expected to increase.[14]

Based on the large reserve of Neodymium, China commands approximately 84% of the global market for neodymium magnets, which is a near monopoly in the market. China is the world's largest supplier and exporter of Neodymium, which is dominating the neodymium market and supply chain.[17]To be specific, in 2021, China successfully exported 6,656.81 tons of rare earth permanent magnets to the United States, constituting approximately 13.69% of the total export volume for such magnets that year. These exports held a value of US$328 million, accounting for around 11.74% of the total export value. Additionally, China exported 6,497.34 tons of rare earth permanent magnets to Germany, which represented about 13.36% of the total export volume. The export value to Germany amounted to US$397 million, contributing approximately 14.24% of the total export value.[18]Japan, meanwhile, has about 15% of the neodymium magnet, but more is needed to compete with China.[17]

Why China has control of the Supply and Demand of Neodymium

There are multiple reasons why China has become a monopoly in the Neodymium market: the lower environmental standards and low-cost workers. In 1985, China implemented a policy that provided partial tax refunds to domestic rare earth producers, effectively reducing costs for Chinese mining companies. Combined with relaxed environmental regulations and low-cost labor, this policy bolstered China's competitiveness in the rare earth industry. As a result, China experienced a remarkable 464% increase in rare earth production between 1985 and 1995. In contrast, the Mountain Pass Mine in California struggled to compete with Chinese producers due to economic and regulatory challenges. Stringent environmental regulations placed additional burdens on the mine, hampering its ability to remain competitive. Consequently, the United States share of rare earth production declined from 34% in 1985 to 6% in 2000, eventually ceasing entirely in 2002.[19]

Neodymium in Politics

Weaponization of Neodymium

As mentioned above, China has a strong power in the supply of Neodymium in the market. Based on this, China has weaponized its country's rare earth elements for a threat. As the primary global supplier, China provides approximately 80% of the rare earths that the United States depends on. These rare earths are utilized in a wide range of applications, including smartphones, electric vehicles, and military equipment. Among the various rare earth elements, Neodymium, which is essential for the production of magnets, is one of them.[20]

In 2018, during the trade war, China weaponized the supply of REE, especially Neodymium and Praseodymium, to react the Trump's tariffs.[21] To be specific, starting in 2018, the United States and China have been involved in a trade dispute triggered by the United States' utilization of Section 301 provisions, which address foreign trade barriers to protect the national industry. As a consequence, multiple rounds of tariff increases have been implemented. The United States has imposed a 25% tariff increase on $250 billion worth of Chinese products. China, on May 29, cautioned that if the United States continues to engage in a trade war against China, there is a significant risk of losing access to essential materials such as Neodymium, which is necessary for sustaining its technological strength through Xinhua, the official state-run press agency of the Chinese government.[22]

In 2021, amid heightened China-U.S. tensions, due to arms sales by Lockheed Martin, Boeing, and Raytheon to Taiwan, the self-governed island that China considers to be its sovereign territory in the previous year, China actively evaluated the option of implementing export limitations on rare earth minerals, which are essential for the manufacturing of advanced weaponry, including the American F-35 fighter jets, which heavily rely on rare earth minerals for crucial components like electrical power systems and permeant magnets such as Neodymium Iron Boron (NdFeB) magnets and other highly sophisticated armaments.[23]

Against China's monopoly; React from other countries

In 2023, in response to recent restrictions imposed by Washington on the export of high-end semiconductors to China, China considered the implementation of an export ban on rare earth metals such as Neodymium and Praseodymium again.[24] Moreover, China has imposed trade restrictions on countries like Japan and Australia due to political conflicts. To prepare for potential similar situations, during the recent G7 summit on May 20th, there were extensive discussions regarding economic security and the importance of enhancing supply chains for essential minerals. The participating nations were committed to decreasing their dependence on China for semiconductors and rare earth elements. The G7 expressed significant concerns regarding the impact of "economic coercion," which involves producing nations exerting pressure through export restrictions. China holds significant importance in the supply chain for electric vehicles, solar panels, and other products crucial for achieving a decarbonized society, as these items rely on essential minerals produced in China. Other countries aim to diversify sources of procurement. However, the G7 acknowledges the challenges in building supply chains that exclude China and intends to urge China to engage in fair trade practices.[25]

Future of Neodymium

Overview of previous contexts

Neodymium is a crucial element within the realm of economics and political sciences, specifically as part of the rare earth elements (REEs). Its significance stems from its extensive utilization of technologies like electric vehicles, renewable energy systems, and defense applications. The predominance of China in Neodymium production has sparked concerns regarding supply security and over-reliance on a solitary source, which carries the risk of weaponizing a specific resource. However, many countries diversify their resources of Neodymium and support each other against China's threat.

Diversifying of resources of Neodymium

The United States of America

In the context of rebuilding a domestic supply chain in the U.S, efforts are underway in several states, including Wyoming, Texas, and California, to extract rare earth minerals. To be specific, MP-Materials acquired the mine and resumed production in 2017. The company aims to become the lowest-cost producer by focusing on Neodymium and Praseodymium, essential components in various industries. Also, the U.S government tries to enhance domestic capabilities by giving grants and contracts to the company, which aims to fully restore the rare earth supply chain in the U.S. by 2025 to fulfill the growing demand in the domestic electric vehicle market.[26]

Australia

Australia is a significant player in the production and supply of Neodymium, a crucial rare earth element. The country's Mount Weld deposit, operated by Lynas Rare Earths, is one of the largest sources of Neodymium globally. Australia's role helps diversify the supply chain and reduce reliance on China, the dominant producer. The government supports the industry through policies and investments, recognizing the economic potential of Neodymium. Australia's contributions ensure a stable supply of Neodymium in the face of increasing demand.[27]

Removal of Neodymium from EVs

Toyota

Toyota has made advancements in magnet technology for electric motors, with the goal of decreasing reliance on Neodymium by up to 50%. The company has developed a new type of magnet that reduces the need for Neodymium while maintaining performance. By innovating in this area, Toyota aims to address concerns about the limited availability of rare-earth elements, ensuring a more sustainable and secure supply chain for electric vehicle production.[28]

Tesla

The recent declaration by Tesla, a major global electric vehicle (EV) company, about their development of a permanent magnet electric vehicle motor that excludes rare earth elements. The announcement by Tesla highlighted the growing importance of reducing reliance on rare earth elements in EV production since China is a major global supplier of these materials. However, the materials that Tesla will utilize as replacements for rare earths are currently unclear.[29]

Conclusion

As a key component in permanent magnets for most notably renewable energy, electric vehicles, and technology, Neodymium has proven to be an indispensable resource with significant economic and political implications. However, the concentration of Neodymium supply in China has significant economic and political implications. Heavy reliance on a single country for this critical resource raises concerns about economic vulnerabilities and geopolitical dynamics. Disruptions in Neodymium supply can impact industries such as renewable energy, electric vehicles, and technology, leading to price fluctuations and supply uncertainties. Diversifying supply sources and investing in domestic mining are crucial to reduce dependence and mitigate economic risks. Furthermore, controlling the Neodymium supply gives China a significant influence, creating potential diplomatic challenges and conflicts for countries heavily reliant on Neodymium imports. International cooperation and strategic alliances are essential to diversify supply chains and reduce geopolitical influence. Collaborative efforts can ensure a stable and secure Neodymium supply, reducing the risk of supply disruptions and mitigating the dominance of any single country. Addressing these concerns is crucial for the sustainable development of industries and to promote a more balanced and resilient global Neodymium market.

References

- ↑ Geoscience Australia. (2023, June 7). Rare earth elements. Geoscience Australia. https://www.ga.gov.au/scientific-topics/minerals/mineral-resources-and-advice/australian-resource-reviews/rare-earth-elements

- ↑ Hvrmag. (2021, October 22). What are rare earth elements & how are they used?. HVR MAG. https://www.hvrmagnet.com/blog/what-are-rare-earth-elements-how-are-they-used/

- ↑ Virginia Department of Energy. (n.d.). Virginia Energy - Geology and mineral resources - rare earth elements. https://energy.virginia.gov/geology/REE.shtml

- ↑ Woodward, A. (n.d.). China could restrict its export of rare-earth metals as a trade-war tactic. here’s what they are and why they’re so crucial. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/rare-earth-metals-elements-what-they-are-2019-6#rare-earth-elements-can-be-formed-by-volcanic-activity-but-many-were-first-created-in-supernova-explosions-at-the-dawn-of-the-universe-before-earth-existed-3

- ↑ Gasdia-Cochrane, M. (2016, May 26). Rare earths update. Advancing Mining. https://www.thermofisher.com/blog/mining/rare-earths-update/

- ↑ Tikkanen, A. (n.d.). Bastnaesite. Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/bastnaesite

- ↑ M. Hoshino, K. Sanematsu, Y. Watanabe (2016). Handbook on the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths. Elsevier. pp. Pages 129-291. ISBN 978-0-444-63699-7.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Tilley, D. (2020, June 17). Rare earth elements. Geology for Investors. https://www.geologyforinvestors.com/rare-earth-elements/

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 U.S. Geological Survey. (2023, January 31). Mineral Commodity Summaries 2023 (pp. 147-148). Mineral commodity summaries 2023 | U.S. Geological Survey. https://www.usgs.gov/publications/mineral-commodity-summaries-2023

- ↑ Kelly, L. (2023, April 9). Rare earths reserves: Top 8 countries (updated 2023). INN. https://investingnews.com/daily/resource-investing/critical-metals-investing/rare-earth-investing/rare-earth-reserves-country/

- ↑ Chemical properties of neodimium. Lenntech Water treatment & purification. (n.d.). https://www.lenntech.com/periodic/elements/nd.htm#Environmental%20effects%20of%20neodymium

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Natural Resources Canada. (2023, February 14). Rare earth elements facts. Natural Resources Canada. https://natural-resources.canada.ca/our-natural-resources/minerals-mining/minerals-metals-facts/rare-earth-elements-facts/20522

- ↑ Ideal Magnet Solutions. (2019, June 12). Samarium cobalt vs neodymium magnets. Ideal Magnet Solutions. https://idealmagnetsolutions.com/knowledge-base/samarium-cobalt-vs-neodymium-magnets/

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Onstad, E. (2021, July 19). China frictions steer electric automakers away from Rare Earth magnets. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/business/autos-transportation/china-frictions-steer-electric-automakers-away-rare-earth-magnets-2021-07-19/

- ↑ Neodymium magnets: Magnet suppliers. Magnet Assemblies | Magnet Information, Companies, Manufacturers & Suppliers. (2023, April 12). https://www.magnetassemblies.com/neodymium-magnets/

- ↑ Lambert, F. (2021, November 10). Countries and automakers agree to go all-electric by 2040 in weak new goal set at COP26. Electrek. https://electrek.co/2021/11/10/countries-automakers-agree-go-all-electric-by-2040-weak-new-goal-cop26/

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Oki, S. (2023, April 6). China plans to ban exports of Rare Earth Magnet Tech. The Japan News by The Yomiuri Shimbun. https://japannews.yomiuri.co.jp/world/asia-pacific/20230405-101753/

- ↑ Research and Markets. (2023, January 27). China Rare Earth Permanent Magnets Export Report 2023-2032: Permanent magnets represent the bulk of Chinese exports. GlobeNewswire News Room. https://www.globenewswire.com/en/news-release/2023/01/27/2596753/28124/en/China-Rare-Earth-Permanent-Magnets-Export-Report-2023-2032-Permanent-Magnets-Represent-the-Bulk-of-Chinese-Exports.html

- ↑ Bhutada, G. (2021, December 3). Rare earth metals production is no longer monopolized by China. Elements by Visual Capitalist. https://elements.visualcapitalist.com/rare-earth-metals-production-not-monopolized-china/

- ↑ Rogers, J. (2019, May 29). China Gears up to Weaponize rare earths in trade war. Science and Technology | Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2019/5/29/china-gears-up-to-weaponize-rare-earths-in-trade-war

- ↑ Stevenson, A. (2018, July 11). How rare earths (what?) could be crucial in a u.s.-china trade war. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/11/business/china-trade-war-rare-earths-lynas.html

- ↑ Sutter, K. M. (2019, June 28). Trade dispute with China and rare earth elements. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/IF11259.pdf

- ↑ Sevastopulo, D., Mitchell, T., & Yu, S. (2021, February 16). China targets rare earth export curbs to Hobble US defence industry. Subscribe to read | Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/d3ed83f4-19bc-4d16-b510-415749c032c1

- ↑ Pilkington, P. (2023, April 11). What China’s rare earth metal ban means for the West. UnHerd. https://unherd.com/thepost/what-chinas-rare-earth-metal-ban-means-for-the-west/

- ↑ Shimbun, Y. (2023, May 21). G7 discuss enhancement of supply chain for essential minerals. The Japan News by The Yomiuri Shimbun. https://japannews.yomiuri.co.jp/politics/g7-summit/20230520-110885/

- ↑ Subin, S. (2021, April 19). The new U.S. plan to rival China and end cornering of market in rare earth metals. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/04/17/the-new-us-plan-to-rival-chinas-dominance-in-rare-earth-metals.html

- ↑ Holmes, F. (2019, November 6). Australia may be the saving grace for the Rare Earth Metals Market. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/greatspeculations/2019/11/06/australia-may-be-the-saving-grace-for-the-rare-earth-metals-market/?sh=12caae3e41cd

- ↑ Toyota Motor Corporation. (n.d.). Toyota develops new magnet for electric motors aiming to reduce use of critical rare-earth element by up to 50%: Corporate: Global newsroom. Toyota Motor Corporation Official Global Website. https://global.toyota/en/newsroom/corporate/21139684.html

- ↑ Global Times. (2023, March 2). Tesla’s announcement it is removing rare earths from its evs sends relevant Chinese stocks tumbling. Global Times. https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202303/1286516.shtml

| This Earth Science resource was created by Course:EOSC311. |