Course:EOSC311/2022/Alberta’s Fossil Fuel Industry: a Paradox of Plenty

Introduction

The economic wellbeing of Alberta has been dependent upon its plentiful, easily accessible, and internationally coveted commodity: oil. Since the beginning of mass scale oil extraction starting in the mid 20th century, Alberta has utilized their abundant natural resources through crude oil extraction and international export to rapidly build up the economy and grow the population[1]. However, the relatively predictable historical success from extracting and exporting crude oil may not remain a dependable, sustainable source of income and economic growth for the province in the long run. This is mainly due to Alberta heavily and selectively investing in this production sector without much diversification into other forms of energy or non-commodity based industries unrelated to oil.[2] Looking at the current activity of Alberta’s oil industry from the most recent decade, it is evident that Alberta has taken a step back from investing in other sectors related to utilizing crude oil in secondary and tertiary local industries, not going beyond simple extraction and export of crude oil. If Alberta’s economy remains mostly dependent upon international external demand for crude oil, the economy will become increasingly volatile to booms and busts of international supply and politics. This will leave the industry and entire economy vulnerable to extreme periods of prosperity and bankruptcy.

Relationship to My Major

As an economics major, my topic of choice for the UBC wiki is the Alberta oil industry and its impacts on the economic prosperity of the province based on how the extracted oil is utilized in primary and secondary industries. This topic ties together the geological study of oil formation and extraction based on module 3 and the economic phenomena of supply and demand apropos to Alberta’s oil industry. Through this topic, I wanted to explore the ramifications of Alberta’s economy being mostly reliant upon the export of a single unrefined commodity and what this means for future economic sustainability. I have specifically chosen this topic because I am very passionate about resources curse economics within the context of Canadian commodities such as crude oil. I enrolled in this course to learn more about how geological formation and later extraction occurs from a non-economic standpoint.

Alberta's Oil Industry

Alberta's Oil Sands

Oil sand is a naturally occurring combination of sand, clay, minerals, water, and bitumen.[3] Bitumen can be extracted using two methods, depending on how deep the deposits are below the surface. Canada’s oil sands are the third-largest proven oil reserve in the world, accounting for 166.3 billion barrels (or 97%) of Canada’s 171 billion barrels of proven oil reserves.[4]

The Athabasca oil sands are the largest segment of Alberta’s economy, making up roughly 30% percent of the annual provincial gross domestic product (GDP).[5] The Alberta government reported that “synthetic crude oil and bitumen royalty [from oil companies] accounted for about $5.2 billion or almost 55 per cent of Alberta’s $9.6 billion non-renewable resource revenue” in the 2013–2014 fiscal year.[6]

The economic benefits of Alberta's oil sands extend beyond the province. Alberta is one of the leading importers of crude oil into the world’s largest consumer of oil; the United States. The oil sands currently contain enough oil to produce 2.5 million barrels of oil per day for 186 years. In 2015, the U.S. consumed 19.4 million barrels of oil per day, making Alberta an resourceful supplier for many years to come.[5]

Oil Extraction and Minor Processing

In Alberta, bitumen, a form of crude oil, can be extracted from the oil sands using two methods depending on how deep the deposits are below the surface: in-situ production or open pit mining.[4] After extraxction, the bitumen is still very slow moving, referred to as having a high-viscocity, and must be upgraded or diluted to be properly pipelined to a refinery.

In-situ Production

In-situ extraction methods are utilized to extract bitumen that is deposited very deep beneath the surface and is not accessible through normal mining, starting at 75 metres or deeper underground.[4] 80% of Alberta’s oil sands reserves are accessible through in-situ techniques with Steam Assisted Gravity Drainage (SAGD) as the most widely used method. This method consists of drilling ttwo horizontal wells, one slightly higher than the other, in the deposit. Then, steam is continuously injected into the top well to raise the temperature in a steam chamber that makes the bitumen have a lower viscosity flow to the well positioned lower.[7] The bitumen is then pumped to the surface.

Open Pit Mining

Open-pit mining is implemented where oil sands reserves are located closer to the surface of the ground, any depth less than 75 metres. Currently, 20% of Alberta’s oil sands reserves are accessible through this mining method.[4] This method utilizes large shovels that scoop the oil-rich sand into trucks which then move it to crushers where the sand is processed through crushing. Hot water is added to the curshed oil sand so it can be pumped through a pipe to an extraction plant. At the extraction plant, additional hot water is added to this mixture in a large separation vessel. The sand-water mixture is then given setting time to allow the various components to separate to allow the bitumen to rise to the surface. After seperation, the bitumen is removed, diluted, and refined further.[8]

Upgrading

Recovered bitumen from open pit mines and in-situ extraction is still too thick for transportation, so it must be upgraded in order to be pipelined and used in refineries. Upgrading transforms bitumen into synthetic crude oil which can be refined and marketed as fuels and can be further processed into other products.[7] The upgrading process involves either adding hydrogen or removing a carbon from the bitumen to create synthetic crude oil, altering the heavy molecules of bitumen into lighter and less viscous molecules.[4]

Current Exports

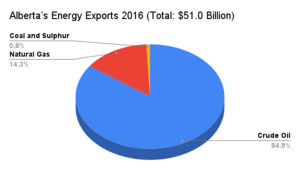

The export of unrefined, crude oil is responsible for a significant amount of Canadian, and specifically Albertain, GDP.[9] In 2016, energy resource exports totaled $51 billion, accounting for almost two-thirds of Alberta’s total commodity exports that year.[5]

Canada produces more oil than it consumes, and as a result, is a significant net exporter of crude oil. In 2016, Canada exported 2.85 million barrels per day of crude oil. Of this, 97% went to the United States and the remaining 3% went to Europe and Asia.[4]

In 2016, Alberta's total energy exports consisted of 86.1% crude oil valuated at approximatly 48.36 billion.[5]

Environmental Ramifications

Oil sand mining has a significant impact on the environment. In Alberta, forests must be cleared for both open-pit and in situ mining. Some pit mines can expand more than 80 metres depth with the removal of up to 720,000 tons of oil-rich sand per day. [6]

Due to the large amounts of energy required to mine and separate oil from the harvested sand, oil sand extraction produces more greenhouse gas emissions than any other form of oil production. The Athabasca mine produces roughly 20 million tons of greenhouse gases in a year resulting from both oil and electricity production for mining.[6] Approximately every barrel of crude oil produced results in the sequential production of 86-103 kilograms of carbon dioxide.[6] The current estimate for the amount of oil within Alberta’s sands that is economically recoverable is approximately 171 billion barrels in 2021.[10] If this oil were to be extracted and converted for energy, it would produce roughly one hundred and twelve billion tons of carbon dioxide, or 28% of the remaining international carbon budget set to meet the climate sustainable goals outlined in the Paris Agreement. [10]

Paradox of Plenty

Resource Curse

A resource curse, also referred to as the paradox of pleanty, occurs when a staple reliant economy fails to maintain stable growth despite having an abundance of natural resources; fossil fuels in this instance.[11] By focusing most production efforts on the natural resource dependent sector, the local economy becomes very reliant on the price of their commodity, becoming volatile to supply and demand fluctuations. In the long run, the curse produces an inverse relationship between natural resource abundance and economic growth, often bringing about poor political, social, and environmental outcomes.[12]

Staple Theory of economic Growth

The staple theory of economic growth suggests that development of early societies, specifically colonial ones, placed a significant emphasis on acquiring and exporting the land’s local commodities, also known as staple goods, to where demand for these commodities was very high and not abundant.[13]According to the staple theory, a commodity-dependent economy will never achieve a position of complete economic self sustainability obtained from industries apart from raw commodity exportation.[13] Neglecting the establishment of additional commodity processing facilities, expansion into other local industries from staple generated revenue, and fully establishing a sustainable economy that can remain stable are all symptomatic of staple resource mismanagement.[2]

To avoid this reliance upon a single commodity as a source of most of the GDP, a staples-reliant economy must diversify beyond exclusively investing most of its labour, time, and money into selective resource extraction and export.[1] The solution is that additional industries need to develop in the region, as a result of the exported staple resource, to support and grow the local economy to the extent to which it is self sustainable, a marker of true economic success.

Alberta's Oil Industry and its Resource Curse

Alberta's staple economy characteristics

Characteristics of Alberta’s current crude oil extraction and export are beginning to bear a very similar resemblance to the symptoms associated with economies that have fallen to the resource curse. [11]Within the context of the paradox of plenty, Alberta is naturally abundant in fossil fuels which should result in the economy progressively growing, yet the wellbeing of the economy alongside the price of oil per barrel drastically and often fluctuates in accordance with the demand for Albertan oil by other countries.[9] With Alberta's total energy exports consisted of 86.1% crude oil. [5] In addition, out of Alberta's total merchandise exports of $78.8 Billion in 2016, 43.2 billion came from crude petroleum.[5] Based on Alberta having such a large segment of their exports and GDP depending on international trade of a single commodity, any change in demand from importers in this volatile market, whether good or bad, will greatly impact the overall economy.

Secondary and Tertiary Industries and the future of Alberta oil sands

Expanding past simply exporting crude oil can lead to secondary and tertiary industries within Alberta and other Canadian provinces that can further process the oil and help balence this issue of unrefined export reliance. Examples of products that can be derived from crude oil include solvents, fibres, plastics, pesticides, kerosene, liquefied petroleum gas, and coatings.[3] Alberta had begun investing in a local petrochemical industry based mainly around turning Alberta’s crude oil and other fossil fuel products into intermediate goods such as ethylene, propylene, butylene and benzene in between 1980-1990, but this investment eventually stagnated in growth. Alberta still remained mostly dependent upon external international demand for oil. [2]

While the petrochemical industry generates more work opportunities than simply exporting crude oil, an economy founded upon the exported commodity is not much better off than a pure resource exporting economy. This is due to the fact that such industries tend to initially provide too few jobs for the amount of investment required and still undergo normal booms and busts. This phenomenon and lack of incentive to branch out into additional industries related to oil after it is extracted from oil sands has led to this illusion of economic diversification.[2]

The size of the domestic market in the staple resource economy is one of the most important and accurate ways to determine the sustainability of the economy, specifically regarding the recycling of income domestically rather than being mostly generated from crude oil trade abroad.[13] It is crucial to transition into this state of stabilization through investing into the initial cost of oil industry diversifiction in order to mitigate the negative reprecussions of the turbulant international supply and demand of oil.[14]

Environmental Impacts of oil industry diversification

Although the industry diversification strategy of crude oil would generate a more stable, self-sustaining economy and through the generation of more jobs alongside secondary and tertiary industries, it does not come without impending environmental ramifications for Alberta, Canada, and the world.[2] Going beyond the risk of commodity depletion and eventual scarcity, crude oil industry diversification leads to environmentally-destructive extraction and upgrading processes as a necessity to achieve a more stable economy.[11] GDP-stimulating endeavours unavoidably produce businesses and workers whose economic interests are invested in mitigating the development of climate-preserving solutions that intrinsically go against climate preservation actions such switching to energy alternatives such as wind, solar or deep geothermal, or reducing the demand for oil altogether.[10] Diversification into the proposed extended industries would draw Alberta and all of Canada into supporting the initial investment sunk costs of recruiting refinery workers, upgrading, and further expansion, ensuring the continuation of oil sands mining activity for decades.[2] Such actions in turn defend the carbon-emitting, conservation-redundant status quo of the current oil sand activity, moving away from transition to a new green economy. Additionally, industry diversification would be enacted on the assumption that the world’s fossil fuel dependency age will undoubtedly continue, and that we can endlessly continue to generate carbon without limit.[10]

Refrences

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Gelb, A. (2014, January 12). Should Canada Worry about a Resource Curse? The School of Public Policy Publications (SPPP), 7 (2): 1-28. https://doi.org/10.11575/sppp.v7i0.42453

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Laxer, G. (2014). Alberta's Sands, Staples and Traps. The Staple Theory @ 50: Reflections on the Lasting Significance of Mel Watkins’s A Staple Theory of Economic Growth. Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, 53-57. Retrieved from https://policyalternatives.ca/publications/reports/staple-theory-50

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Chastko, P. (2004). Developing Alberta's Oil Sands: From Karl Clark to Kyoto. Calgary: University of Calgary Press, (pp. 72-93). ISBN: 1-55238-124-2, 978-1-55238-124-3

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Government of Canada. (n.d.). Oil Sands Extraction and Processing. Retrieved June 22, 2022, from https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/our-natural-resources/energy-sources-distribution/fossil-fuels/crude-oil/oil-sands-extraction-and-processing/18094

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Government of Alberta. (2017, May 13). Highlights of the Alberta Economy: 2016. Alberta. Government.https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/10989a51-f3c2-4dcb-ac0f-f07ad88f9b3b/resource/513eef5f-aa53-4cde-888d-8e52822b6db4/download/sp-eh-highlightsabeconomypresentation.pdf

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 NASA Earth observatory. "Athabasca Oil Sands". NASA. Retrieved June 21, 2022.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Gow, A.B. (2005). Roughnecks, Rock Bits and Rigs: The Evolution of Oil Well Drilling Technology in Alberta, 1883-1970. Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 38-56. ISBN: 978-1-55238-067-3

- ↑ Macfadyen, A., & G. Watkins. (2014). Petropolitics: Petroleum Development, Markets and Regulations, Alberta as an Illustrative History, 19–34. University of Calgary press. ISBN 978-1-55238-769-6

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Heyes, A., Leach, A., & Mason, C. F. (2018). The economics of canadian oil sands. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy, 12 (2), 242-263. https://doi.org/10.1093/reep/rey006

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 McKibben, B (July 28, 2021). "We Love You, Alberta—Just Not Your Tar Sands". The New Yorker.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Toni, Z. (2020). Conflict, Capture, and Inequity: A Case for the Resource Curse in Alberta. On Politics,13 (2), 53-69. ISSN 1718-1011

- ↑ Keay, I. (2014;2015;). Immunity from the resource curse? the long run impact of commodity price volatility: Evidence from canada, 1900–2005. Cliometrica, 9 (3), 333-358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11698-014-0118-6

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Innis, H.A. (1999). The Importance of Staple Products. Canadian Economic History: Classic and Contemporary Approache, edited by M.H. Watkins and H.M. Grant, 15–18. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- ↑ Dubé, J., & Polèse, M. (2015). Resource curse and regional development: Does dutch disease apply to local economies? evidence from canada: Resource curse and regional development. Growth and Change, 46 (1), 38-57. https://doi.org/10.1111/grow.12064