Course:EOSC311/2020/Archaeology & Geology

Historic Earthquakes through Archaeology & Geology

"In recent years, considerable progress has been made in ‘archaeoseismology’ and there is a greater awareness of the need for collaboration between archaeologists, geologists, engineers and workers in other disciplines, to evaluate the traces of earthquakes in excavations, both for understanding their effects at the site and for the information they can provide about the nature of the earthquake implicated."[1]

Statement of Connection

I chose to look at the connection between archaeology and geology through these examples of historic earthquakes because they demonstrate why this interdisciplinary approach is so important. Both archaeologists and geologists look at events that from the past (geology just usually looks at a much larger scale of events!) and so it makes sense that they often overlap and intertwine. In these examples, historic earthquakes are looked at and analyzed using both disciplines. What results is a greater understanding of the events.

In order to prepare for possible earthquakes in the future, data about past earthquakes is very important.[1] However, seismic data has only been taken for around a century.[1] Given that the geological time scale is so vast, that data is not representative of overall trends in earthquakes.[1] For example, an area that has not experienced major seismic activity in the last 100 years may not be the quiet zone that we think it is as it could actually be an area where a major earthquake will take place, it's just that earthquakes usually take place every 500 years there[1] Therefore, looking at the historical and archaeological record is helpful because it can help extend back that seismic record even further, helping to predict earthquakes in the future. [1]

Umm-El-Qanatir site

The Umm-El-Qanatir site in Northern Israel shows signs of occupation until the mid-8th century.[2] Through archaeological and geological methods, it can be proven that the abandonment of this site is related to the earthquake that took place on January 18th, 749 CE.[2] This site is located 10 km east of the Dead Sea Transform (DST).[2] This transform fault has been the site of many large earthquakes with magnitudes of up to 7.5 with the latest, large earthquake being in 1837 CE.[2] These earthquakes have caused damage to the archaeological sites in the region, which means that past seismic activity can be seen in the archaeological record.[2]

The village is made of several buildings, including the synagogue, which is the largest in the region.[2] In the synagogue are several buried farm tools underneath the rubble.[2] None of the tools or other artifacts (like masonry) are from after the 8th century.[2] This indicates, using the archaeological record, that Umm-El-Qanatir was abandoned after the 749 CE earthquake.[2] These artifacts can be definitely dated to the 8th century due a political shift from the Ummayad Caliphate to the Abbassid Caliphate.[2] The capital shifted from Syria to Baghdad, Iraq.[3] This would have heralded a new artistic and architectural style that would have been distinctive enough to be detected in the archaeological record.[3]

The village also includes a spring area where a spring fed into a water pool.[2] Due to the earthquake, this was displaced by approximately 1 metre.[2] Given that the water pool was never fixed, it can be determined that the site was abandoned soon after its destruction. The likely cause of damage is a landslide because of the steepness of the slope of the spring area, the weakness of the red clay that it was built on, and the water present.[2]

By calculating Newmark displacement, which is an index value that determines how the soil slope is likely to react during seismic activity, Weschler et. al were able to determine the distance and magnitude needed to cause the landslide.[2] This showed that the magnitude needed to be quite high. Even if the epicentre of the earthquake was just 5km away, a magnitude of around 6 would still have been necessary to cause the landslide.[2] At a further distance of 15 km away, the magnitude would have needed be around 7.[2] Therefore, it can be concluded, using geological methods, that Umm-El-Qanatir landslide was caused by an earthquake with a magnitude of 7 or possibly even higher.[2]

The village was likely abandoned due to a landslide that spring area of the village.[2] This was important to the economy of Umm-El-Qanatir as it supported flax and textile industries that supplied trade goods.[4] So, its destruction likely motivated its abandonment. This landslide would have been triggered by a large earthquake and given that the Dead Sea Transform (DST) is the only fault in the area that could cause such a large earthquake, it can be determined that an earthquake from the DST was the cause of the abandonment of the village.[2] While the landslide could be attributed to a number of earthquakes over times from the DST, with the archaeological evidence tied to the dating of the artifacts, it can be determined that the 749 CE earthquake is the cause of the landslide that led to the abandonment of the Umm-El-Qanatir site.[2] This is significant in that it shows the value of using both archaeological and geological methods in determining past earthquake activity.

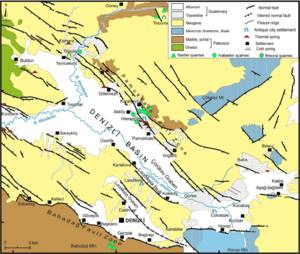

Denizli basin earthquakes

This example looks at how using archaeological and geological data can be used to analyze past earthquakes and predict the potential for future seismic events. The archaeological findings at Laodikeia and Hierapolis confirm geological estimations of magnitude for historical earthquakes in the Denizli Basin, approximately 6.8 or higher.[5] This is important for the future of the basin as well, as it helps to determine what future earthquakes there might look like.[5] The horizontal displacement of the fault line in Hierapolis is between 10 cm and 1 metre and vertical displacement is approximately 65 cm.[5] This correlates to a magnitude of 6.5 or larger as magnitude is dependent on both the area of the rupture surface as well as how much displacement occurs.[6] These destructive earthquakes would have occurred throughout history in years such as 60 AD, 494 AD, and in the early 7th century AD.[5]

In Hierapolis, earthquake damage has left a mark in various ways such as damaging irrigation channels as well as structures.[5] For example, a latrine building was completely destroyed due a powerful earthquake.[5] Through archaeological excavation, 6th century coins were found, which means that the earthquake that knocked down that particular structure was the one that occurred in the 7th century.[5] Additionally, the North Byzantine Gate was also harmed by strong earthquakes. The presence of 6th century coins also dates this natural disaster to the 7th century earthquake.[5] These examples demonstrate the importance of an interdisciplinary approach as through both geological and archaeological methods, these events can be specifically located within both geological and historical context.

Additionally, with the collapse direction of many of the columns and walls trending in the NE or SW direction, this indicates that the Pamukkale Fault, a NW or SE facing fault, is responsible for the larger, more powerful earthquakes in the region. This shows how an archaeological artifact can determine and influence geological conclusions and be beneficial for predicting future seismic activity.

Conclusion / Your Evaluation of the Connections

In these examples, it is clear that approaching these earthquakes from both an archaeological and a geological perspective resulted in a better understanding of the events. This shows how, even though we tend to think of issues through the lens of individual disciplines when dealing with real research topics in your career you're much more likely to take a collaborative approach with people and methods from other disciplines. This is especially important for university students to understand and take advantage as we mostly tend to otherwise focus on our faculties and majors. Especially with regards to archaeology and geology which are two disciplines that deal very much with past events and so the exchange of methods and research is much greater. This project has shown me how you can get a much more complete and interesting research topic by exploring other disciplines in relation to your own.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Ambraseys, N.N. “Earthquakes and Archaeology.” Journal of Archaeological Science, vol. 33, no. 7, 2006, pp. 1008–1016., doi:10.1016/j.jas.2005.11.006.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 Wechsler, Neta, et al. “Estimating Location and Size of Historical Earthquake by Combining Archaeology and Geology in Umm-El-Qanatir, Dead Sea Transform.” Natural Hazards, vol. 50, no. 1, 19 Nov. 2008, pp. 27–43., doi:10.1007/s11069-008-9315-6.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 “The Art of the Abbasid Period (750–1258).” Metmuseum.org, www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/abba/hd_abba.htm.

- ↑ “Ein Keshatot, the Golan Heights' Hidden Archaeological Gem Opens.” The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com, 22 Oct. 2018, www.jpost.com/israel-news/culture/ein-keshatot-the-golan-heights-hidden-gem-opens-to-the-public-569111.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 Kumsar, Halil, et al. “Historical Earthquakes That Damaged Hierapolis and Laodikeia Antique Cities and Their Implications for Earthquake Potential of Denizli Basin in Western Turkey.” Bulletin of Engineering Geology and the Environment, vol. 75, no. 2, 2015, pp. 519–536., doi:10.1007/s10064-015-0791-0.

- ↑ Panchuk, Steven Earle. Physical Geology . 2nd ed., BCcampus, 2015, opentextbc.ca, opentextbc.ca/geology/.

| This Earth Science resource was created by Course:EOSC311. |