Course:ENGL419/Books/Vocabolario

Introduction to the Vocabolario degli Accademici della Crusca

Volume 1 is the first of 6 volumes in the 1741 private reprint of The Vocabolario degli Accademici della Crusca (vo-cab-o-lar-ee-o di-gli A-cad-em-each-ee di-la cr-oo-sca), which was published in Naples. The Vocabulary of the Academics of the Crusca is a repeatedly reprinted Tuscan dictionary printed in Italy by an organization known as the Accademia della Crusca, also known as the Academy. First published in 1612, the Vocabolario continued to be printed until the mid-19th century as a resource for the original Tuscan language. Volume 1 of the fourth edition was produced in Naples in 1741 by Guiseppe Ponzelli and is the only edition from the Accademia della Crusca to have been published outside of Venice and Florence. [1]The fourth edition was the first to be divided into 6 separate volumes: A-C, D-I, L-P, Q-S, T-Z.

History

History of the Vocabolario

Volume 1 of the 1741 Vocabolario was published in Naples under a private reprint contract with a publisher named Guiseppe Ponzelli. Published 5-10 years after the Academy released the fourth edition of their Vocabolario, Ponzelli's stays true to the strict Crusca's fourth edition format by being published in six volumes and containing the same acceptable words with which adhere to the Academy's guidelines. While the reason for the private reprint is unknown, it can be suggested that it was done to spread the pure Tuscan language further than those who lived in Tuscany. The Vocabolario was later published again in Naples in 1746 and in Venice in 1763 but this edition was the first to be published outside of Tuscany, showing the Academy’s drive to spread the Tuscan language. The first Italian dictionary was published in 1516, showing that the Academy was quick to become involved in the compiling and distributing of the Italian language. For more information on the history of the Vocabolario, click here: Vocabolario History)

Physical Description and Contents

Volume 1 of the fourth edition of the Vocabolario delgi Accademici della Crusca is quite different than that of the previous editions published, both private and large scale. For starters, this edition is about twice the size of the 1746 edition; measuring 28.5cm long, 46cm high, and 6.5cm wide. The outside of the book is rather plain: it’s binding made out of semi-flexible material covered in what appears to be a dark purple leather that was stretched around both the front and the back. Once that cover was securely placed on, the Academy placed two pieces of multi-colored cloth on the front and the back covers over-top of the original leather material, leaving only the corners and the side binding visible. This thin piece of cloth is decorated in purple-pink, white, yellow, and brown colors in a wavy pattern from left to right. On the side binding are the words "Vocabulario de la Crusca" in faint gold lettering on the top of the binding written on a piece of black leather, with the roman numeral "I" on another piece of black leather leather on the bottom.

Now, I will describe of the physical look of the book, as well as the contents within.

Beginning Pages

The inside to this particular volume is rather interesting, as it varies greatly from other editions, but also from the other volumes in the fourth edition. The pages of the dictionary are of a dark beige color, which could be due to deterioration and time, and vary in content based on where in the book the reader is. The first page of the dictionary is mostly blank, with the words Vocabolario Degli Accademici Della Crusca. Tomo 1.” in large black capital letters. Flipping to the title page, one can see the use of different fonts and styles evident, such as bold and italics. Also, there is the use of both all capital font, and standard sentence structure – the beginning of the first word and of nouns are capitalized with the remaining letters being lower case. Instead of using numbers to list the date,it is displayed with roman numerals: MDCCXLVI. This is the only time throughout the first volume where roman numerals are used. The title page also contains a picture, of which I will outline later on.

Preface

The beginning of the dictionary starts with a 10 page prefazione, or preface, which is divided into 9 lengthy sections. If the reader is not able to read or understand the Italian or Tuscan language, then the content of the preface is unknown. Although, it can be seen in this edition, due to the sheer size of the edition and volume, that the Academy included numerous new words into their strict guideline of acceptable words in the dictionary. This is because in the 18th century, there was a rise in the study of everyday language, or what became known as “language with no authority”. [2] This caused dictionaries to include these “everyday” words alongside their traditional or archaic terms, which the Academy focused on. Therefore, the preface outlines the reasons for the additions into the Vocabolario since the first edition was released, due to it going against their goal of purifying the Tuscan language. The preface ends with a note that the additional words are ones of “non-routine” and that the reader and society at large should speak and write the Tuscan language with style and grace, leaving the decision to include the “everyday” language up to the speaker. It should be noted that there are no page numbers for the preface, with “Page 1” indicating the beginning of the actual dictionary entries.

Guiding Features

On the bottom of the each page, The Academy included the first couple letters of the next word that appears first on the following page. This was done as a guideline for the publisher in order to maintain the order of the pages during the publication process. Coinciding with that of other dictionaries and books of this time period, the bottom of each page contains the beginning 2-5 letters of the first word on the next page. The variation on length is due to whichever word was coming up next, depending on the commonality or definition of that particular word. The reason for this was to make sure the order of the pages for printing and publishing was accurate and to allow the reader and publisher to know what page or word should come next. This guideline assisted in lengthy publications and prints, such as this one, as the mix-up of pages occurred frequently during the publication process with which it is expensive and time-consuming to fix mistakes.

Multi-Definitions

Much like modern-day dictionaries, this volume contains multiple definitions for certain words. These range from variations of the word and its definitions, but also includes the phrases and examples in which these variant meanings could be used. These are marked by a double-S shape and are indented below the original definition. Beside the double-s shape are the roman numerals to help indicated the number of extra definitions there are for this particular word, as well as added references to various works by famous authors who were deemed acceptable by the Academy. Throughout the dictionary, the majority of words contain no added definitions, but those that do have them tend to vary anywhere between one to five extra definitions. For example, in the picture on the right, the word "A bada" translates into "at Bay" and then each sub-definition outlines the various contexts that this word can be used with that are not the same as its standard definition; the first says "Tenere a bada" which means Keep at Bay; the second says "Stare a bada" which means Stay at Bay; the third I am unsure what the words are; the fourth states "Stare alla bada d'uno" which means Stay at the Bay of One. Beside each of these are references to various authors and there works where these sub-definitions can be found.

These add added depth and knowledge to the Tuscan language that the Academy is attempting to purify.

Entries

The entries themselves show the breadth and detail that the Academy went into when researching, compiling, and publishing this volume and edition. Not only are the definitions themselves lengthy, but they contain large amounts of information in just a few sentences. Included with the word and the definition, are references to authors such as Dante and Galileo. [3] This contrasts from the Academy's previous editions due to the inclusion of authors who are not from Tuscany, as well as modern authors, as previous editions made note to include strictly traditional Tuscan authors. In these references are specific passages from their works, such as passages in Dante's Divine Comedy. Furthermore, in these definitions are translations for the same words into Greek and Latin. The order of the entries vary throughout the entire dictionary, with some words being classified as a noun, verb, or adjective; some being described as a masculine or feminine word; some are adjectives or definitions of other words found in the dictionary. There appears to be no uniform listing for the entries throughout the dictionary, however the words do contain some basic qualities throughout: the translations, references to authors, and, of course, definitions. This lack of “unity” shows the depth and breadth of the Tuscan language but also is a bit confusing as one would assume that the Academy would wants to have the same structure throughout the entire Vocabolario in order to maintain the unity and purity.

The detail of the definitions shows the increasing ability to print and the variations of print available in the 18th century, at the time of this volumes publication. Each entry has included in it the styles of italics, all capital letters, and regular typeface throughout the definition: italics are saved for the translations of the word into Greek and Latin as well as some definition purposes such as classification of noun/verb/adjective/adverb, and references to specific authors; all capital lettering is used for the word that is being defined; and regular sentence structure for description of the word as well as reference to other works. The mixture of italics and regular sentence structure illustrates the care and detail put into the compilation, but also the variety of typefaces available.

Another interesting detail to the entries is the inclusion of the abbreviation V.A. This is seen throughout the dictionary beside specific words and it is meant to classify words that the Academy saw as inadvisable to use in Tuscan speech and writing. [4] They included these words because even though the Academy had a focus on archaic words, these V.A words were seen as “too archaic” and therefore deemed inadvisable. [5] However, nowhere in the this edition of the Vocabolario is this information mentioned, unless it is somewhere in the lengthy preface, with which a non-native speaker would not have understood.

The entries are split according to alphabetical order, as with the trend in dictionaries, in order to easily locate a specific word. In the Vocabolario degli Accademici della Crusca, each page has the word headings on the top of the page in order to show the order of the words and which section the reader is in. Upon the end of one section and the beginning of a new one, the new section is shown in large, bold capital letters. This is consistent throughout the dictionary as each section of letters is only divided as such by their first two letters. For example, there is a new heading for AS and AT, but there isn't one for ASP or AST. However, the top of the pages show the progression of the words (AT -> ATA -> ATE, etc) giving the reader an understanding of where in the AT section of words there are in inorder to navigate through the Vocabolario.

List of Errors

A unique factor about this volume is that it has a list of errors in the back of the Vocabolario after the lists of entries are completed. Entitled "Errori Di Stampa" or Printing Errors, the list includes numerous different kinds of mistakes made while printing.These largely include simple spelling mistakes where they mixed up an “n” for an “m”, or forgot an accent, to bigger errors where they put in the wrong translated Greek or Latin word in. This is interesting because one would assume that that being a Vocabolario, the Academy would make sure there are no errors before publishing the book. However, this illustrates the difficulty in printing books in the 18th century; how despite how careful the publisher is when putting together a book, the process is complicated, especially with the various machines needed to do so. The smallest of errors are included in the list, which shows the Academy’s dedication to preserving the integrity of the language. These pages are not numbered and are listed in alphabetical order of word entry.

Collected Works

At the end of the book is a list of works by authors which the Academy approved of prior to publication. Called the "Guinta di Vocaboli" or Guinta Vocabulary it starts off with a long letter written by the publisher Guiseppe Ponzelli, before listing off the authors works. The list is organized by the word in which the author is associated with or referenced to. Organized this way and with the lack of page numbers, the reader has to look for the specific word they are interested in. Starting off at AB and ending at CU, the list makes evident the authors approved by the Academy. Alongside the authors and their works is the place in the work that the word is used and the significance behind it. This allows the Academy to continue their role in preserving Tuscan writers and their works by showing how significant they are in the purification of the Tuscan language.

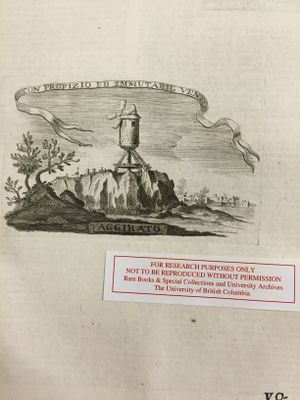

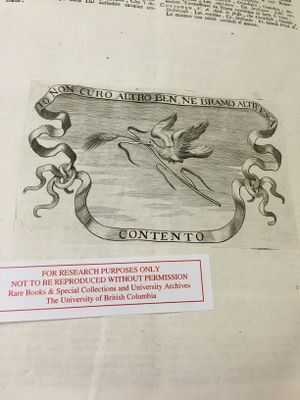

Pictures

Throughout the Vocabolario, there are pictures placed at the end of each section of A, B, and C. These pictures are traditional imprints which can be seen by the pressing marks surrounding the pictures. This is because in order to put the picture on the page, the publisher needed more force from a separate machine, causing the mark to occur. I would assume these pictures are made out of wood engravings which was soaked in ink before being placed on the page.

The pictures at the end of the sections are very much different from eachother. The first one, at the end of the A section, shows a small windmill situated on top of the cliff , with the outline of city buildings in the background and three small trees on the left side of the foreground. On the top of the page are the words "Con Propizio Ed Immutabil Vento" or With Favorable and Unmovable Winds in a wavy banner, and on the bottom is the word "Aggirato" in which I do not know the translation of.

The second picture is of a plant of what appears to be corn with a bird on one of the branches. Nothing is around the plant, but in the background are some mountains and a couple buildings placed at the bottom of one of the mountains on the left hand side. On the top of the page in a banner ,similar to the on at the end of A letters, are the words "Secondo Lei Convien Mi Regga E Pieche" of which I do not know the translation of, and on the bottom is the word "Posato" which means "Placed".

The third and final picture of the sections is of a bird, identical to the one in the previous picture, carrying a branch of the plant in its mouth as it flies in the sky. There are no buildings or mountains, and the entire border is made up of a banner. The top of the banner reads "Io non curo altro ben, ne bramo altr'esca" which loosely means "I am not healed well, nor I crave other the lure" and the bottom reads "Contento" which means "Happy".

Another picture that is inside the Vocabolario is on the title page, which illustrates naked angles - identified by their wings - completing various tasks: wheel spinning, pouring ingredients into the vat, the sifting of ingredients, and the catching of the final product. The angels appear to be in an open room with a city view. On the top of the page are the words "Il Piu Bel Fior Ne Coglie", which loosely translates into "The Most Beautiful it Grasps".

The meaning behind these pictures is uncertain to me due to the lack of literature and knowledge about these dictionaries and their history. The above is just a outline of the contents of the picture as I am not an art historian or scholar on old Italian lexicographers and illustrators.

Historical Significance

The Vocabolario is an important work for both the history of the Italian and Tuscan languages for many reasons. For one, it signified the rise of literacy and publishing in Italian society, as well as showcasing the increase in education. The Vocabolario was created not only to purify the Tuscan language, but it symbolized the growth of the language and Italian printing. With the Vocabolario being published during what was known as the "Age of Dictionaries", it allowed Italy to flourish and grow as force in the book world, specifically where dictionaries were concerned. While dictionaries were being printed elsewhere in the world such as England before Italy began to produce them, the Vocabolario shows the popularity of languages and printing in society, as well as the vast amount of technique, time, and style needed to print something of this caliber. The Vocabolario shows the combination of different styles, texts, and formats used during the publication process. It is one of the most important works of the history of the Italian dictionary due to other dictionaries, both at the same time and after the Vocabolario, following what became known as the "Crusca format", imitating not only the layout, but the ways that the Academy compiled and organized the Vocabolario; It quickly became the standard way to publish a dictionary.

Works Cited

- ↑ Accademia della Crusca http://www.accademiadellacrusca.it/en/accademia/history/fourth-edition-vocabolario-1729-1738-and-suppression-accademia-1783

- ↑ Beltrami, Pietro G. and Simone Fornara. "Italian Historical Dictionaries: From the Accademia della Crusca to the Web." International Journey of Lexicography, 17.2 (2004): 364.

- ↑ Ibid., 362.

- ↑ Ibid., 362.

- ↑ Ibid., 362.

The following are the works I have cited both on this page and the Vocabolario History page:

“Accademia della Crusca.” Encyclopedia Britannica. The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica, n.d. Web. 19 April 2015.

Accademia della Crusca. Vocabolario degli Accademici della Crusca. Naples: Guiseppe Ponzelli, 1741. Print.

Accademia della Crusca. Web. 19 April 2015. http://www.accademiadellacrusca.it/en/accademia/history

Belgrami, Pietry G. and Simone Fornara. “Italian Historical Dictionaries: From the Accademia Della Crusca to the Web.” International Journal of Lexicography, 17.2 (2004): 357-384. Web. 19 April 2015.

Carmichael, Montgomery. In Tuscany: Tuscan Towns, Tuscan Types and The Tuscan Tongue. London: John Murray, 1901. Print.

Coluzzi, Paolo.” Endangered Minority and Regional Languages (‘dialects’) in Italy.” Modern Italy, 14:1 (2009): 39-54. Web. 19 April 2015.

ouLearn on YouTube. “The Age of the Dictionary – The History of English (7/10).” Online video clip. YouTube. YouTube, 24 June 2011. Web.