Course:ENGL419/Books/Education Books of New England

By Liam Scanlon

Come take a journey through the educational series of schoolbooks from America's most crucial era. Just what did these kids learn about life through them? Just what will you learn? Just what will you learn about yourself?

Some of the most monumental shifts in thought occurred during the late colonial and early Republican period, and much of this change is registered in the four education books here. Through examining them, we can find fundamental shifts in modes of thinking about education, liberty, patriotism, religion, and what it means to be a 'normal' American child.

This wiki can be approached from any order and any fashion, although it is recommended that you begin with "the Books Used" and "New England Primer" sections by way of framing the material, and ending with the "Reflection." Beyond that, explore to your heart's content, and with your personal, Lockean natural freedom, using your personal, Lockean rational brain.

The Books Used

Isaiah Thomas’s A Little pretty pocket-book, intended for the instruction and amusement of little Master Tommy, and pretty Miss Polly, 1787

- Founder of the American Antiquiarian Society in his hometown of Worcester, Thomas is considered to be “one of America’s greatest printers” from the time (Rosenbach xlii). Thomas helped to circulate some of New England’s most popular children’s books, including Pilgrim’s Progress and abridged versions of Clarissa and Robinson Crusoe.

- Probably the most intriguing aspect of the book is the opening letter from Jack the Giant Killer, in which he tells Little Tommy and Little Polly that “that you was a good boy; that you was dutiful to your Father and Mother,” but that sometimes “you did bad” (Thomas 15). In some ways, the use of Jack, as a beloved childhood hero for the time, could almost be similar to the use of movie mascots of today (where, in say Pixar and Dreamworks movies, the characters are still used in somewhat not-so-canonical ways in order to teach kids valuable lessons).

- A couple clues about the fashion in which the book has been written leads me to conclude that Thomas intended the book to be read aloud to children, and not alone. First, the opening letter from Jack directly integrates the children’s ‘Nanny’ into the story, with Jack telling the kids (in that beautiful meta-theatrical way which is always easier to do in children’s books) that their Nanny will given them a ball to play with (so that the Nanny would probably have to be there in order to give it). Secondly, there isn’t an alphabet included in this one, something which, by 1787, would have been highly circulated thanks to the Primer. Thomas, with his knowledge of the publishing industry, must have intended the book to be a communal experience, intended for the bonding of the child with his family.

The United States pictorial school primer, designed as a child's first book. (Date Unknown, sometime in the nineteenth century)

- This book was clearly greatly inspired by (if not completing ripping-off) The New England Primer, with a similar use of the alphabet and simple pictures. However, the book reflects a much more secular approach to pedagogy, with only very rare instances of God, thus moving towards a vision of life which is not necessarily organized around religion.

- Fischer and Brother, run out of Philadelphia, seems to have been a fairly flourishing printing company for its time, with many of their books available for online perusal. Some of these enjoyable books include The Fairy World, Grandpa’s Forget-me-not, The Lincoln and Hamlin Campaign Songster, or, the Continental Melodist, and Christy’s Plantation Melodies (okay, so some are cute, some not-so-much).

Noah Webster’s An American Selection of Lessons In Reading and Speaking. Calculated to Improve the Minds And Refine the Taste of Youth.

- Although Webster today is one of the most widely known early Republicans thanks to his dictionary, his own life was often unstable (both financially and emotionally), and subject to upheaval (perhaps representing, in some ways, the upheavals of his age). Joseph Ellis says of Webster that he, as a true man of the Enlightenment, brought “the intellect of a philosophe, the cupidity of a capitalist… and the compulsiveness of a young man on the make” (165). It’s these characteristics which lead him to further conclude that the man “embodied the conflicting characteristics of the emerging nation”; indeed, it was precisely his concerns about those very ‘characteristics’ of that very ‘nation’ which so empowered him, throughout these long periods of upheaval in his life (165).

- Webster’s book, published in 1802, reflects many of these concerns. While he never explicitly says what age he intends the book for, the tone he takes implies that the book is intended for school boys around the age of twelve. This makes the book different than the other three covered here in two crucial aspects: in the age range it’s interested in, as well as a focus on a more generalized, systematic education intended for entire groups of boys (versus the focus on the individual children of the family in the other three).

The New England Primer

No children’s pedagogical work from the period had anywhere near the impact that the New England Primer did. Paul Leicester Ford, as our nineteenth century editor of the work wrote in his 1899 introduction that the work was “the Little Bible of New England” (1). Truly, it can be said (and will be seen) that all the works analyzed here have stemmed in some way from the Primer. And, like all good things colonial American, it had its beginning in Britain. Its likely creator Benjamin Harris had already been a publisher of children’s books in Britain, where an early edition is believed to have already been produced (though no copy exists today) (Roberts 499). Once being threatened by the law for his virulent anti-Catholicism after the rise of King James II, Harris escaped to America, and The New England Primer began to appear in Boston.

Kyle Roberts notes how Boston, with its 12 000 residents and four printing shops, was the ideal starting ground for the book, and its popularity ensured that, by the 1740’s, Philadelphia and New York were printing hundreds, then thousands of copies, a year to be circulated across the colonies (499). Bibliographers estimate that between three and eight million copies of the Primer were made, and Roberts admits that even these margins have dubious reliability (Roberts 492). By the end of the eighteenth century, the book was available in a geographical range of London to Pittsburgh, Portland Maine to Lexington Kentucky, and could be bought from bookbinders, booksellers, printers, or town peddlers (Roberts 494).

Its enormous popularity ensured that there would be many books which would try to copy the book’s structure. Roberts says of the Primer that “in one sense, the publishing history of [the book] is a history of printing in early America”: beginning its life as a reprint of an English text, only to pierce its way into the interior of the country over the course of the century, following revolutions and republics (518).

The fundamental purpose of the primer is to instill religious piety in the children it is teaching to read. Leicester speaks highly of the book’s power for moral improvement, spurred on precisely because the book never pretended such spirituality would be easy. “Here was no easy road,” he writes, “to knowledge and to salvation; but with prose as bare of beauty as the whitewash of their churches, with poetry as rough and stern as their storm-torn coast, with pictures as crude and unfinished as their own glacial-smoothed boulders,” the children would be taught in such a way that “they were afraid they ‘should goe to hell,’”; but “no earthly or heavenly rewards were offered to its readers” (Ford 2).

Indeed, the book is almost entirely devoted to religious instruction informed by the grim Calvinist worldview, but what makes this interesting is the variety by which such philosophy can be found, despite its religious determinism: from Bible passages, official prayers, prayers made up for the book, scenes from martyrs, and even a kind-of mock-kids psychomachia where the Devil and Jesus battle for the soul of a “Youth” (67). Apparently, despite the evident belief in Divine Absolution, the writer (Harris or others) tries to help the child towards salvation through ‘any option necessary.’ This ‘any option necessary’ approach to teaching children can be seen more and more in other books as the era progresses.

Crucial to this moral reform was the unfailing belief in the reformatory power of reading. Ford points out how Protestants understood better than most at the time the immense value of reading:

- “no mass or prayer, no priest or pastor, stood between man and his Creator, each soul being morally responsible for its own salvation; and this tenet forced every man to think, to read, to reason… Unless man could read, independence was impossible, for illiteracy compelled him to rely upon another for his knowledge of the Word; and thus, from its earliest inception, Puritanism, for its own sake, was compelled to foster education” (4).

This explains why the book, despite its high diction and minimal use of pictures, takes great care to teach the children how to read, from the alphabet to its use of pictures beside key scenes. Stephanie Schnorbus notes how, thanks to their rarity, pictures are only given to parts of the book which the editor of the Primer deems important, and the only two places which gain consistent illustrated attention in different editions are the alphabet and the martyrdom of John Rogers (262). The alphabet, often the most interesting part of the book for scholars, is one of the rare places in the Primer itself which seems to reflect Locke’s understanding of child education (see 3.1), as it combines spiritual instruction with educational instruction, finally supplementing the two aims with a series of pictures.

The martyrdom of John Rogers, however, places the book firmly within Puritan tradition, as it gives emphasis to the pain and suffering of Christianity rather than any of its benefits. Rogers comes to be known to Protestant society by way of John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, but Ford notes how Rogers was a Catholic priest before conversion. Somewhere between the Book of Martyrs and The New England Primer, he then argues, English Protestants must have added a wife and ten kids (ten kids!) to his legend (Ford 100). Many scholars have also noted how the Rogers martyrdom never changes, despite just about every other aspect of the book going through significant rewrites and edits. Apparently, when all the rest of New England saw tremendous evolution over the course of the century, the Rogers martyrdom was placed, symbolically always in the middle of the book, to remind the colonists about the ideological ‘core’ of the community.

The Subtle Revolution(s)

Meanwhile, some of the most dramatic changes of the era are evident in the alphabet. Indeed, these transforming couplets most clearly recognized the changing ideologies of its surrounding era. The only stanza which, symbolically, does not change is the one relating to Adam and original sin (Ford 58). But then, the letter K transformed in major editions six times:

- Original: “King Charles the good/No Man of Blood”

- 1727: “Our King the good/ No Man of Blood.”

- 1791: “Kings should be good/Not men of blood.”

- 1797: “The British King/ Lost States thirteen.”

- 1819: “Kings and Queens/Lie in the Dust.”

- 1825: “Queens and Kings/ Are gaudy things.” (Ford 59-61)

In a single letter, an entire transformation of a system of belief can be registered. The couplet of the initial edition might be accepted as a somewhat innocuous assertion of royalty, but each update registers a shifting push: by 1797, the book takes on a tone almost like bragging, and by the editions of 1819 and 1825, it’s all royalty who are negative. Significantly as well, only the first edition chooses to give a name to said monarch; after that they were (apparently) not worth the trouble.

Perhaps even more intriguingly, the book begins to replace the ideology-free animal couplets with patriotic phrases of approval, as in the case of W:

- Original: “Whales in the sea/God’s voice obey”

- 1794: “By Washington/ Great deeds were done.”

- 1825: “Great Washington brave/ His country did save.”

The 1794 version, while clearly expressing admiration, could just be read as a quote of instruction for children in their first forays into reading. By the 1825 version, however, Washington’s heroic status has been gratified: not only was he ‘brave,’ but he also ‘saved’ the country. The word ‘save’ implies two things: that the country was in desperate need of saving (as opposed to words surrounding ‘independence,’ which more implies a disagreement), and that Washington was so valiant he saved the country alone (and if not alone, certainly at the helm of things—there is never, for example, a Jefferson or Franklin couplet). By the 19th Century, we see an increasing trend for books to idolize the American patriots, both in couplets as above and in pictures.

Ford, however, finds other revolutions surrounding the book’s production less praiseworthy. He notes, with some disgust, that the changes made after 1790 declare that “‘the Naughty Girl… was to have none of the ‘orange, apples, cakes, or nuts’ promised to ‘pretty Miss Prudence,’ and the naughty urchin was only threatened with beggary while the good boy was promised ‘credit and reputation.’” (Ford 100). This cause-and-effect outcome, he asserts, is markedly different than the divine retribution-or-damnation approach which marked the initial editions. Most seriously, the penalties for being unable to read have changed: in earlier editions, the rule would connect illiteracy with being unable to read the Bible (which would, in turn, connect with damnation), whereas the new edition states that “He who ne’er learns his ABC/Forever will a blockhead be./ But he who learns his letters fair/ Shall have a coach to take the air” (Ford 100). Such a shift registers the growing connection between literacy and wealth but also (more importantly) the tremendous good such a wealth brings, enough so that it takes the place in the Primer of any greater salvation—“it should have made the true Puritan turn in his grave,” Ford opines (100).

This adaptability to the times would ultimately lead to mixed results of success. Roberts argues that it was precisely this “fluid and open nature” of the book which allowed its longevity and relevance (496). In the early republican years, the book only became more popular—while the outbreak of the American revolution forced men and women to rethink everything, “they still embraced The Primer as a text on which to build the new nation’s literature” (Roberts 519).

For Ford, however, it was precisely this feeble push to adapt to the changing times that would spell the Primer’s doom: “the printers having one found how much more saleable such primers were, and parents having found how much more readily their children learned, both united in encouraging more popular school-books, and very quickly illustrated primers, which aimed to please rather than to torture, were multiplied” (109).

And so, by the 1850’s, the New England Primer was a relic of the recent-past, as it could no longer keep up with the growing trend to (gasp!) make children’s books fun. The Primer, after all, would always depict the martyrdom of John Rogers, and kids no longer wanted to read such a dire account. But while the book would be succeeded by more enjoyable books (such as ones to be examined here), the Primer would always be recognized as the mother of children’s books in the Thirteen Colonies.

Sidenote: The Revised Edition

“The New England Primer made a brave fight, but it was a hopeless battle. Slowly printer after printer abandoned the printing of editions of the little work, in favor of some more popular compilation. It was driven from the cities, then from the villages, and finally from the farm houses. Editions were constantly printed, but steadily lost its place as a book of instruction… The New England Primer is dead, but it died on a victorious battle field, and its epitaph may well be that written of Noah Webster’s Spelling book: ‘it taught millions to read, and not one to sin’” (Ford 113).

Paul Leicester Ford writes what he sees as a fitting epilogue (if not eulogy) for the Primer, yet in doing so says as much about himself and his own beliefs as it does about the Primer. Unfortunately, little could be found of Ford himself, though his extremely vocal commentary surrounding the Primer’s evolution gives one much to go off of. Speculatively, I imagine Ford to be some cranky academic in some old college in New England, shut up in his grand library, poring over a series books too-old even for him. Staring into the book, he imagines with glee what pre-Revolution America might have been like—even though it was only a century before him, the transformations wrought by iron and industry are so great the country is almost unrecognizable. Peering into the older copies, he gets a vision of a pre-Industrial society which posited God and not gold as its guiding goal.

Ford would likely have played into the trend Roberts charts in his own paper, of this growing need in the nineteenth century to memorialize and in turn revitalize the appeal of the Primer. It reflected many conservative American’s concerns with the open market ideologies which dominated Golden Era America, and in turn decided to look back towards what they saw as a ‘golden era’ of spiritual community (Roberts 517). However, in the move to create a ‘proper’ version (with correct typefaces, standard-press thanks to industrial measures), the very act of making this new edition “made it something foreign and unknown, a curious relic of the past” (Roberts 518). In this sense, the revised edition itself comes to be an example of changing perceptions of the nation in tandem to the growing need for the process of memorializing (or even mythologizing) the origin story to a still-very-young country.

Pedagogy and Ideology

What can be seen over the course of the eighteenth century in America is a change in how children could (and should) be instructed. In this transformation, John Locke, particularly through his 1693 text Some Thoughts Concerning Education, has been referenced by countless children’s literature scholars as the fundamental theorist for the transformation (if not the beginning) of children’s literature in America and Britain. Indeed, Gillian Brown would argue that changing modes of education would also come to form changing modes of philosophical understanding.

A new appreciation for Locke’s educational strategies began to take favor over dominant modes of Calvinism. The writings of John Calvin and his belief in divine absolution was the fundamental tenant of Puritan philosophy. Calvinists, as an advanced literate society, saw a constant a tension between knowledge and faith, as even though knowledge (instilled through reading) was crucial to forming a conception of God, only God Himself could give that person an understanding of His true form (as any misrecognition would only result in idols) (Schnorbus 256). Overwhelmingly, any knowledge gained must always be brought back towards furthering oneself towards salvation. Therefore, while knowledge alone was unreliable, “the combination of this knowledge and God’s redeeming work in a person allowed true knowledge” (Schnorbus 257). This leads Schnorbus to conclude that a pedagogical text centered around Calvinist theology would show explore key religious doctrines while emphasizing the child’s needs for salvation and the consequences of evil deeds; pictures would be rare, and God would not be depicted at all (257). Early editions of the Primer present such features in abundance.

Locke’s ideas opposed such a bleak outlook and religious determinism. Rather, he saw the mind as a blank slate where one acquired knowledge through their five senses (Schnorbus 258). Children learned by example, and as such books should teach children through stories and their morals rather than by oppressive doctrinal phrases and commandments (Schnorbus 258). This transformation saw a shift from Calvinist ideologies, that childhood “was just corrupted adulthood,” to Locke’s vision of childhood being a separate stage of life with its unique promises and limitations (Schnorbus 252). The Lockean approach saw the child as an “active partner” who would “respond to the text, evaluate text and image together, and compare written information with past experience” (Schnorbus 253).

Understanding that shift from Calvinist modes of education to Lockean is crucial, as where the former saw “depraved, fallen, willful little beings,” the latter saw “blank slates who learned everything (including the capacity to do evil) through their senses” (Schnorbus 286). Such a shift in some ways comes to explain the mania with which eighteenth century Americans viewed education: a child being born into tabula rasa presents tremendous promise and tremendous danger—no longer guaranteed a place in Heaven, it now was left to the parents and the educators to instill in the child both a love of learning and a love of God, before it was too late.

Loving Learning

For Locke, having the child come to love learning was of crucial importance in the entire education project (Schnorbus 263). If the child wasn’t given a love of learning at such a young age, they would never love it, and such a catastrophe, Locke asserts, would be the greatest failure of an educational system. As such, children should be taught in a variety of ways which shows the fun in learning, be that through games or pictures (Schnorbus 264).

So while The New England Primer only relies on pictures for its alphabet, many education books which would follow it demonstrate a great deal of intellectual debt to Locke’s ideas. The United States School Primer illustrate just that: in many ways the book is greatly influenced by The New England Primer, especially in its attention paid to breaking down the alphabet and phrases at the beginning. However, the book has hundreds more pictures than the New England one, and also seeks to use new industrial methods of book coloring to further catch the children’s eyes. Children need to learn, yes, but in the case with books like The United States School Primer, they probably had fun with it as well.

Isaiah Thomas, when crafting his Little Pretty Pocket Book, recognizes that children need to play, but creates a book full of games so as to “teach [children] to play all the innocent games the Good boys and Girls divert themselves with” (16). Thomas tells the parents that when teaching their child, “take care to do it in such a manner, as to forward his enquiries, and pave this his grand pursuit with pleasure” (10). Learning must be made fun from the earliest of ages.

His book, then, makes games educational at the same time that he’s making education a game. With such considerations, it’s not surprising that Thomas was one of the most popular New England book publishers for children.

Learning for enjoyment’s sake comes to represent a profoundly different school of thought from those of John Calvin. The children’s books of the early nineteenth century come to represent exactly how much American society had changed since the Mayflower.

Associations and Determinations

The ultimate goal of such instruction would be that, eventually, the child could teach himself, in his individualist way, all that needed to be learned. In A Little Pretty Pocket Book, for example, the country boy “learned his book to that surprising degree that his Master could scarce teach him fast enough,” the book says with great praise (Thomas 74). “Learning,” he concludes. “is a most excellent thing, and easy to be acquired too, when little boys set themselves earnestly about it” (Thomas 74).

On this path towards individual determination, Brown argues, the child needed to learn through association, where “children must examine those ideas that they find linked together in their minds” (qtd. in Brown 30). As such, books force children to associate concepts with characters and characters with concepts beyond their immediate physical scope; books force the child to move beyond their immediate surroundings.

For example, the opening of the Primer alphabet reads “In Adam’s Fall/We sinned all,” which teaches the child about Adam at the same time that the insertion of the picture of Adam brings his story into the present—with Adam in the moment of action, it’s “an encounter, still in progress” (Brown 37). In this way, Adam’s sin becomes the child’s sin; rather than something which occurred at the dawn of time, original sin is one committed every day by children like the reader.

With a similar idea but different process, fables were important because they inserted morals which were not directly related to the story, and as such forced the child to think beyond the present scope of the story. One story Brown relates is worth telling here in order to really understand this.

In an Aesopian Fable from Dilworth’s A New Guide to the English Tongue, a man takes pity on a dying snake, and so brings the snake into his home, but once the snake wakes up he bites one of the man’s children and the child dies. The moral of the story reads, “Ingratitude is one of the blackest crimes that a man can be guilty of” (Brown 64). Brown (quite humorously) retorts that “ingratitude is not the first term that comes to mind when one encounters a killer snake. Indeed, a much more immediate and plausible meaning to take from the fable would be do not trust snakes” (65).

But the power of fables is that, in supplying an unexpected interpretation to a seemingly straight-forward story, fables force the children to evaluate “not just the relation between themselves and a text, but also the relations within a text,” between fable and moral (Brown 61).

This can be most distinctly seen in Thomas’s games, which take up the majority of his book. Through his forced interpretation:

- flying a kite shows “soon as though seest the Dawn of Day, to God thy Adoration pay” (25)

- dancing around the maypole: ““Leave God to manage, and God to grant/ That which is his Wisdom sees thee want” (26)

- Chuck-Farthing: “Chuck-Farthing, like Trade,/ Requires great care;/the more you observe,/The better you fare.” (24)

- Thread the need: Talk not too much; fit down content,/That your discourse be pertinent” (29)

- Fishing: “Learn well the motions of the Mind; /Why you are made, for what designed” (30)

- Leap Frog: “Just so ‘tis at Court;/Today you’re in place;/Tomorrow perhaps,/You’re quite in Disgrace” (46)

Throughout this (very extensive) list, Brown’s point about abstraction becomes reinforced.

Teaching kids, through fables and picture tales, to make assertions for themselves was highly important for the workings of American society. But there’s a flipside to this connection: in the forcing of the child to associate with Adam, Brown argues, that child “becomes aware of his own capacities,” capacities of which can be evil (in terms of original sin) but also great in consequences (Brown 39). Getting the child to make his own assertions was very useful to the Puritan educator, but that very encouragement of association would, perhaps, one day go too far: just how far could religious determinism take the critical individual?

Sidenote: Revolutionary Ideologies

In The Consent of the Governed, Gillian Brown makes an intriguing argument about the impact of children’s books on early American society which is worth considering here.

Brown argues that, over the course of the eighteenth century, new ideas about childhood were being informed by new ideas about consent. The Lockean notion of consent posits that all humans are born in a state of natural freedom, but consentingly give up some of those natural freedoms (openly or tacitly) to a sovereign in order to enjoy certain basic rights and comforts. In different works, Locke compares this consent given towards a sovereign to the consent a child gives to its parents for similar kinds of comforts. While this is an analogy of Locke’s, Brown creatively takes it to be real as, she argues, such notions of consent and childhood really comes to inform Locke’s (and by proxy future American’s) views on education.

This activity of informing consent “inaugurates the modern information age” for her, as it showcases the tensions between individual freedom and the different informational modes of the growing consumer society (43). In a world where consumer goods are expanding at such a rapid rate, parents showed increasing concern about what a child would learn, the Puritans of the late colonial period were always at a risk that these practices of self-determination meant that the child may choose to find salvation outside of the spiritual community (especially when salvation might be increasingly found in money).

But as these kids grew up, notions of consent not only informed that subject’s relation with their parents, but also form their relations with their king—and if that king was no longer deemed worthy of respect under rule, then such consent was liable to be withdrawn. Brown argues that “It might be said that the ideal of consent of the child stands as the origin story of the American republic.” (23). Such an education of an individual to be discerning, Brown concludes, would be carried with them as they grew up, where with each generation children would be more individualist, more Lockean in their own assertion of consent (and the power to remove it) until they finally chose to ‘remove’ their consent of the British crown permanently.

Brown’s thesis is a provocative one, but one which tends (in relying on this notion of ‘consent’ and child agency) to simplify an extraordinarily complex movement—how does this figure in, for example, with geopolitical relations (against France), or the changing religious climate of newer immagrants to the thirteen colonies later in the eighteenth century, or the rising urban population, or the populations relationship with the Indigenous groups they interacted with? In short Brown, as a literary scholar, undermines key movements that ultimately makes her argument two-dimensional at best.

However, the argument can come to work on a symbolic level in explaining the dramatic shifts in ideology over the course of the eighteenth century, as New England transformed from a close-knit, traditionalist community culture, to a rapidly industrializing mercantilist vision looking towards modernity. In giving children the power of consent—to choose what and how they read, forcing them to make assertions of their own about what they’re reading—an entirely new class of Americans were born.

Shifting Beliefs: The Rise of Rational Self-Interest

Such a fundamental shift in the notion of consent has repercussions in the religious dimension of the texts; indeed, Paul Leicester Ford’s fear about the shifting of morality in texts away from God toward more ‘worldly concerns’ is probably fairly well-placed. In The United States Pictorial School Primer, for example, the actions of children are phrased in a distinctly more cause-and-effect fashion than the New England Primer. In assertions like:

- “Bow wow, barks the Dog, as he runs past us. We will not vex him. Some of the bad boys tie tin-cups to his tail, and then he runs till he drops down dead” (p. 28)

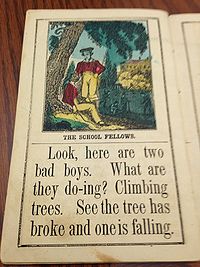

- “Look, here are two bad boys. What are they do-ing? Climbing trees. See the tree has broke and one is falling” (p. 34)

- Charles and Jane are good kids, “They often received presents form those who loved them, as good children always will. they are very much amused with the donkey which they got from their uncle” (p.33).

Nonsensical as some of these consequences may be (a donkey—really?), what’s important is that the kids are not directly going to Hell (or in the third case, Heaven) because of their actions; their actions, rather, have immediate impact in the world around them. This subtle shifts reveals a fundamental new way of configuring the world: the land where children live is no longer just a proving ground for the heavenly life beyond it, but rather salvation—or at the very least, joy—can now be found right here, right now.

The United States Pictorial School Primer, make no mistake, makes mention of God, but those references to Him are squeezed near the back of the book on two facing pages. In the first, “Three Happy Children,” the story reads, “Come, little girl, you must not cry, because the bird is dead, we all must die… The name of God is great, His anger is terrible” (p. 30). This terrifying closing message certainly calls back to the more ‘fire and brimstone’ approach of early American society, and yet on the facing page is Grandpa’s “Moral Lessons,” where a child is told that “God is the parent of all… if he bid us live, we live, if he bid us die, we die” (p. 31).

While still adopting the grim absolutism of divine ordination, the resulting message is one of far greater optimism than that which would be found in the New England Primer: God’s love is everlasting—he created you, didn’t he—and that love can only be something to be rejoiced about. Secondly, if God can “bid us to die,” at any time, then what’s the point of worrying about when that will be? Que Sera Sera. The fact that the grandpa, of all people, is telling the child this just shows that the matter is not particularly important for daily life.

A scene such as the one with the grandpa and the dead bird denotes the immense complexity of faith in Antebellum America, which increasingly saw itself rooted in worldly concerns, but which still paid a (however superficial) deference to a Lord above. The countryside setting of the book (as will be explained in 'normalcy') gives a strong possibility that the book was made by Puritans or at least other old American families, meaning that this shift is unlikely to be because of new immigrant families with different religious beliefs. Rather, it’s a shift that shows a fundamental transformation in how faith is viewed and used.

A Little Pretty Pocket Book, though published decades before the above mentioned Primer, goes one step further. Jack the Giant slayer gives Little Tommy “a Ball, the one Side of which is Red, the other Black, and with it ten Pins… for every good action you do a pin shall be stuck on the red side, and for every bad action a pin shall be stuck on the black side. And when by doing good and pretty things you have got all the ten pins on the red side, then I will send you a Penny… but if ever all the pins be found on the Black Side of the Ball, I will send you a Rod, and you shall be whipped, as often as they are found there” (Thomas 17-18).

Rather than rely on God, Thomas instead forces the guardian to create the physical consequences of action: it does not stem from God alone. In speaking to parents in his forward, Isaiah Thomas tells them, “let him study mankind; shew him the springs and hinges on which they move; teach him to draw consequences from the actions of others” (10). At no point is the Bible mentioned. The end of the eighteenth century, then, shows a growing recognition from pedagogical booksellers that the pretense of God’s judgment alone will not be enough; material objects are needed to create that incentive (indeed, the use of the penny, it seems, would position the child for a life of seeking reward through money, and so here would come industrialized capitalism). It’s also significant to note that the person giving these children instruction is not God or one of the saints but Jack the Giant Killer, a secular fantastic hero who has no outward connection to Christian ideology.

By Webster, God has been taken out of the picture almost entirely. Webster expressed on many occasions his disdain for religion, finding it “only a milder form of tyranny” and “an insult to humanity, a solemn mockery of all justice and common sense” (qtd in Ellis 170). Further, his declaration that the people should “leave sacred things for sacred purposes” leads Ellis to conclude that Webster created, in his writings, “the first secular catechism to the nation state” (175).

An American Selection of Lessons illustrates this in many ways. His schoolbook, not reflecting any specific dogma or framework, uses liberal humanist approach to culture, borrowing from Shakespeare, Milton, and Machiavelli (yes, in a book probably intended for twelve year olds). Sometime these passages are quite Christian, but many are not (one wonders what lessons children are supposed to learn from the final “Signifying Nothing” soliloquy from Macbeth). He takes Thomas’s commandment to “show children the workings of mankind” to a new level, placing man’s achievements on the kind of pedestal which would have brought Harris to the point of Puritan despair.

The secularization of American culture is often seen as a nineteenth century phenomenon in response to the revolutions, both industrial scientific and social, which so transformed society. But careful examination of the children’s textbooks demonstrate minor transformations which would have tremendous consequences in coming generations. Webster lies on the dramatic far end of that spectrum, and indeed, most of his works (including his dictionary) were not widely adopted until decades after he died (Ellis 211). For most, such an openly secular approach would have been seen as far too radical, and even less would have been comfortable teaching their children such lessons.

But the 1723 edition of The New England Primer ends with the decree to “sow the seeds of grace while young,” so that “when thou com’st to die,/Thou mayst’ sing that triumphant song/Death where’s thy victory” (80). Such a long reward can no longer guarantee a child’s attention by the end of the eighteenth century: new incentives were required in the here and the now; pennies to be given, balls to be thrown. And when those children of revolution grew up, they would become the men of the early industrial era, using all the same tactics for acquiring the incentives that they would have learned as children.

The Normal Child, the American Child

Scenes of Normalcy

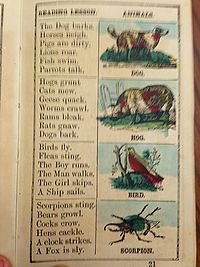

The United State Pictorial School Primer takes place somewhere in the countryside, and seems to expect its audience to live there as well. Images run throughout it which give name to the things the child would see in its immediate surrounding: squirrels, goats, frogs, tortoises, snakes, pigs, and different types of birds. Occasionally there will be a strange moment of the exotic (like the ever-perplexing addition of elephants and scorpions), but overwhelmingly these images seem to have been created to allow a child to understand their immediate world. The children are given at the same time a series of declarations about life: “horses neigh; pigs are dirty; lions roar; fish swim; parrots talk; hogs grunt; cats mew; the boy runs; the man walks; the girl skips” (image 2, p. 21).

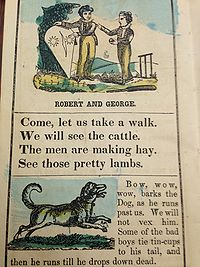

These images are further augmented by more complicated scenes of rural life: farming, fishing, shoemaking, and the school. In one scene, Robert tells George, “let us take a walk./We will see the cattle./The men are making hay./See those pretty lambs” (image 1, 28). The book is telling the child the same thing: come, see the pretty farm, come and see the world as it stands around you. In learning to read, the child also learns to appreciate his own place and context. Created at some point during America’s transformation through the industrial revolution, the book refuses to acknowledge rapid urbanization or any modern tools of society such as the steam engine or the factory.

(With, however, one major exception: The Steamship, which is pictured more than once and is also described to takes the produce of one country to be disposed of in another” (p. 32). Apparently ships are crucial to telling kids about global capitalism, but why the ship is discussed and other modes of transport are not I could never quite grasp the meaning of).

These scenes of the countryside come to portray an image of the idyllic, where children can play and learn in peace. The very fact of it being the countryside, however, gives immediate assumptions about class: these children probably belong to old American families who have enacted the pastoral lifestyle for generations, so different from the Irish, Polish, and Italian children coming in droves at the very same time to settle in the crowded, messy, dangerous cities. Living in their bubble, these children must know none of that. Such classist notions are reinforced by the children’s aristocratic habits, of petticoats, felt jackets, caps, and dress pants, so they resemble something close to the mini-aristocracy of the Victorian era.

A Little Pretty Pocket Book, for example, tells the story of the stork and the crane, where the crane leads the stork so amiss that he eventually ends up in Hell. “You see my Dear,” the moral of the story reads, “the sad effects of bad company; if the poor harmless stork had not been in company with the wicked Crane, he probably have lived till this day,” and it’s easy to see how such a moral would be employed by parents to make sure their kids stay out of ‘bad company,’ bad company which may have come from a ‘bad family’ (a Catholic one, perhaps?) (p. 69).

Book and Gender

These assertions of what is ‘normal’ and what is ‘foreign’ come to play greatly into assertions of gender. The aforementioned declarations about life in The United States Pictorial School Primer concludes with, “the Boy runs./The man walks./The Girl skips” (p. 21). The assertion is tiny, minor even perhaps, but the very subtlety of makes it so totalizing: it is assumed that the boy (in his giddiness) will run around, it is assumed he will one day grow up and learn to walk in an orderly fashion, meanwhile the girl must skip (implying a sense of utter frivolity, as opposed to the boy running which, while being overly energetic, still gives a sense of ambition).

Significantly, the mother is not mentioned at all (she would probably just be sitting—who wants to read about someone sitting?). In the same fashion, Webster does not make the distinction between boys and girls because he is only writing to the boys: girls would not attend the types of schools he’d intend to read his book.

Power is the dominating value for boys at the same time that subservience is for women. In the “A Walk in the Fields” picture from The United States Pictorial School Primer, for example, a boy, holding a riding crop, points out to the cornfield while the girl looks on with dismay (image 3). Although there are no words beyond the title given to the scene (and as such it’s impossible to ever really tell what’s going on), there’s a very clear sense of power involved: the boy with his riding crop is ordering something to the girl with her flowers. One holds the power, one holds the beauty.

In A Little Pretty Pocket Book, while the boy is praised for his intuitiveness and sense of adventure (as mentioned in 'pedagogy'), the little girl is praised for being “extremely dutiful to her Parents and Governess, kind to her School-fellows, and obliging to everybody… works well with the needle” (Thomas 75). It’s this kind of meekness and subservience, Thomas concludes that “made everyone fall in love with her” (75). Boys are valued for their ambition, while girls for the very opposite.

In the aforementioned letter Jack gives to little Tommy (see 'shifting ideologies'), he gives the identical letter to Polly, only this time the object which becomes the one of moral guidance is not a ball but a pincushion (Thomas 21). In taking pains to reprint an entire letter on valuable paper in order to only change the object of reward, Thomas makes a point of delineating the masculine and feminine spaces: the ball, as a symbol of the outdoors, is intended to be played with by Tommy, while the pincushion, as the symbol of the indoors, is intended to be used by Polly. And thus, the nineteenth century separation of the public and domestic spheres was born.

Tommy and Polly can come to stand for the dual symbols of the ‘normal children’: that there is only a single name for each gender implies that there is only a single class of people the work is addressing; that there is a distinction between boy and girl shows that, despite their classist similarities, their differences cast a wide gulf between them. Children reading these books would learn these distinctions and be told to follow them. And while their parents would have likely made similar assertions of gender, to have it printed in writing makes the distinction that much firmer. The book forces them to become.

The American Child

After a child’s place in the family and his surroundings have been confirmed, it was crucial to have their sense of the nation reaffirmed. Patriotism is the last lesson to be learned by the end of the eighteenth century. “Through the process of learning to read and the experience of certain reading materials,” Brown writes, “the colonists came to think to themselves as Americans” (Brown 3). From the revolution onwards, the “project of American identity within children” would be instilled through “distinctly American” textbooks and references, along with “dictionaries, spellers, readers, geographies, histories, and arithmetics” (Brown 57). So what does it mean to be American in the antebellum period? What kind of values must be inculcated for the proper American citizen?

Much of what gets to be known as the ‘American’ lifestyle would be asserted through the aforementioned images of what is ‘normal’ for ‘An American Kid,’ but sometimes more outright declarations of patriotism would be required. Pictures of different American heroes are interspersed throughout The United States Pictorial School Primer, such as this terrifying picture of Benjamin Franklin, and a bust of George Washington which resembles a Roman one (pg 12 and 33).

Both pictures are inserted into their surroundings without context or seeming reason: Franklin exists around a series of useful household words, while Washington is interposed over a story about “Charles and Jane” being very kind to each other.

Their random inclusion implies a kind-of afterthought, as if the publisher suddenly realized at the end that they needed—somewhere—a couple pictures of the nation’s heroes. Perhaps the very randomness of their busts are placed there in the hopes of inculcating a sense of curiosity in the child, so that they will go and ask their parents what it might mean.

At the same time, these images play, contextually, into the various scenes of American country life. Washington ‘exists’ facing a bird, while Franklin builds himself a cocoon of images of household affection. In this sense, the patriots exist within the natural American landscape of the child.

Noah Webster’s own American Selection of Lessons seeks outright to fashion an American ideology. Webster, Joseph Ellis writes, “saw himself as a founding father with an unprecedented opportunity to shape popular attitudes” (165). Understanding, more so perhaps than most of his contemporaries, that the end of the independence war was just the beginning of the real revolution, saw that forging a national culture distinctly separate from Britain was imperative (Ellis 164).

Of fundamental importance to this national project was the education of children, for “the impressions received in early life usually form the character of individuals” (qtd. in Ellis 165). His 1802 text An American Selection of Lessons demonstrates just that. Intended for young schoolchildren, the work tries to encompass all that a child will ‘need to know’ as they become citizens of the new republic. “In the choice of pieces listed here,” he writes, “I have been attentive to the political interests of America… the writings that marked the revolution, which are perhaps not inferior to the orations of Cicero and Demosthenes, lie neglected and forgotten” (2). Webster attempts to set this right.

The work is a disorganized scattering of clips and quotes from various genre and subject, occasionally interspersed with Webster’s own beliefs. Despite the sense of chaos which comes from a perusal of the work, certain patterns emerge, as Webster attempts to create something close to a genealogy of knowledge and the arts over the centuries leading towards the apex of independence. His writing was always informed by the belief that “American was destined to succeed Greece, Rome, and more recent European powers as the capital of civilization,” and this meant simultaneously that America must understand the greatest moments of these civilizations at the very same time they would overcome it (Ellis 170).

This scope stretches from The Republic, to Cicero, to Shakespeare. America, though a young nation, is the inheritor of that ancient tradition, and Webster is the architect of what gets placed in it and what does not. In one section is a description of Iceland; in the next is a passage from Paradise Lost; in the next is a history of the independence war. There can’t be much in the way of a logical connection between the three, but their very juxtaposition of forces children to read (or at the very least acknowledge the presence) moments of great patriotism at the most random moments. Like the visual cues in The United States Pictorial School Primer, the kids can’t quite seem to escape the ever-floating spectre of their patriotic hero—whether they want to know about the war, or they just wanted to read about Iceland.

Webster’s approach in creating a national narrative might seem amateur and uneven by today’s standards (especially when, through the twentieth century, national images have become so successful and total in their manipulation), but the important idea is the evidence of the desire to create a mythos which links people across vast spaces, combined with the knowledge that the best targets are those too young to discern the outcome of such an education.

Fifty years after Webster’s book on education, “Patriotic Series for Young Boys and Girls” implemented the national project with a thoroughness and rigor which would far exceed Webster’s attempts. Aided by new tools of industrial expenditure, the Patriotic Series gave children books about the great patriots like Andrew Jackson and Arthur Brown, as well as giving the “heroic story” of the birth of the Liberty Bell.

Pioneer Mothers of the West in particular cites the power of the book in inculcating nationalism: in describing the valiance of the women in fighting off the “bloodthirsty savages” who attack their families during westward expansion, the book simultaneously manages to demonize the land’s First Nations while at the same time creatively justifying an America which spanned the entire continent. In only fifty years, an entirely new conception of America can be witnessed through such books, and yet at the same time it’s precisely those books that helped to cast the spell of the myth of the nation in the first place. America, in many ways, was born through such pedagogy.

Reflection

Talking to various Peers of 419, I’ve come to see that for almost all of us, there comes (after months and months of searching for just the right one) that moment: love at first sight with their rare book. Mine came with that now-infamous (to our class, at least) page of The United States pictorial school primer, depicting the “Three Happy Children” who learned (with scarce-contained glee) that they were all going to die and that God was really terrible. There’s just something so bizarelly blatant about its construction that (to a Twenty-First Century reader) it approaches Monty Python-levels of satire. From then on, I knew that educational textbooks were the way to go.

Little did I know that this happy drawing would become a big monster of a project which grew far beyond me being capable of handling it all (kind of like Webster’s vision of America: with horror, by his 1843 death, the country had already grown so far beyond any kind of ideal republic, instead becoming a “nightmare of liberalism”) (Ellis 178). It meant researching and cutting, cutting and researching, until more portions of the work studied was left out than left in. It was, in the end, an undertaking that makes a fitting end to one helluva degree.

But it managed to cover so many educational realms I’d never been able to dive into before now. There’s something peculiarly tantalizing about the late Puritan period: to imagine the transformation of a close-knit sectarian society centered around duty, obligation, and piety, towards the boisterous, explosive, and unfailingly confident society that suddenly looks a lot more like the America we know today. As with France in the same period, the dramatic upheavals inaugurate the modern era, and as such so much of the modern age can be informed by such transformations of ideology.

This project has shown me how far some of the roots of these ideologies go. In looking at children’s educational books from the era, I’ve been able to see how the most powerful nation in the world was born—naturally, it was born in the minds of children. Thanks to the rigorous scholarship of Gillian Brown, I’m able to see how, even as early as The Primer, children, in being taught to assert, to connect, to grow, would grow up to be the rational critical individuals that would see so well the sense of Locke’s ideas, and who would in turn begin to teach their kids in an even-more Locekan way.

Perhaps they’d give their child Isaiah Thomas’s (Lock inspired) pocket book: look here now, it’s little, it’s fun, it’s got Jack, son, your favorite hero! That child would learn to expect a penny for every time he did well, and when he grew up and the British denied (or at least, took a large portion of) that penny, well then, he’d take to the streets and demand self-rule. Then maybe his son would go to a school molded by Webster, who would learn about a new sense of destiny given by God to all the little children: this land is great, but you, you are greater, the product of all the greatest moments of the West and subject to none of their folly; you will create a new Republic.

Of course, there’s a major caveat for each of these commandments given, and that is that the American child was a white Protestant boy. My greatest regret with this project is that it’s already too large to discuss at all the underbelly of this new vision for childhood: the plantation melodies. Or about bodies such a nation would be made off from, and how a book like Pioneer Mothers of The West would glorify the deaths of millions in the name of westward progress. For those of the caveat, there would be no place in this new rational republic.

For women, there would certainly be a place for them, although it would be one which would always be ‘placed; in the shadows: indoors, under the guidance and gaze of her future husband. Early modern considerations of gender have never hit me quite so hard as when I read through these children’s books: from a very young age, girls—running around outside—would be brought in and forced to read this; they’d be given a pincushion and a needle and told to sit still and stay. For the next century thousands of the books I’ve described or others like them would be bought and taught to the young and impressionable lady. Seeing all these young women in petticoats and bonnets, the girl’s place in her own world would be sanctified.

In the end what stays, unsettled, in my mind is image 3, “Walk in the Fields,” wherein the boy forces the girl to watch the cornfields. She looks a little uneasy around the boy, but finds she can’t help but listen. The boy holds the riding crop out towards her. Just how would the girl and the boy grow up then? Would kids reading this book learn to interact in the same way with each other?

And it’s fitting that on the last day of my undergrad (writing this, no less, from an abandoned classroom in the education building) that I would look at the kind of books that started kids (like they started me) out on some sort of wild, rompin’ education adventure. (Indeed, it’s hard not to turn this reflection into less about Americans and more about myself, the way I’ve been transformed by all that I’ve learned at UBC in the last four years—more than anything, probably, since those early impressionable years).

So what kind of power did those books have on American children at the dawn of the Republican era? Through this project I have tried (however superficially) to trace those connections through notions of spirituality, gender, processes of normalization, and nationalism. That’s great, yeah, but then: what kind of power do books ‘like that’ have on me?

It’s scary to think, upon reflection, about how little of those books I actually remember. When I do I remember flashes of them—Good Night Moon, The Little Engine that Could some Robert Munsch book or another—those flashes are fleeting, and even then I wonder if it’s not just the memories I have of revisiting those works once I was a little older, say seven or eight. By then I’d gained some Lockean powers of discretion and assertion, and was able to say proudly that I could read Harry Potter, and so therefore those little kids books were ‘stupid.’

But really now, what kind of imprint did that make on my psychology—the castles upon hills molded in my head through the process of reading or being read to? Going back to Locke again, the notion of the blank slate individual, however many times it’s since been debunked, still has enormous sway over our culture, as we think we can change kids through books and products and games and people. Maybe we can.

And I think about my gorgeous, golden-curled nieces, born in the Age of the Apple, and I wonder what messages they’re getting and what they’re getting into—every day from every angle, their parents allow them the I-Pads, their teachers use smart boards. The world of the internet (and its blackened heart, somewhere around the seventh-circle of 4Chan) is only a click and a misclick away for them.

And I think about my own process of growing up and the messages that destroyed and rebuilt me: growing up gay in the early-2000’s and still finding there’s still no space for you in a world that’s not R-Rated; growing up a little artsy and a little weird in a culture that sees profit margins before it sees people—all those messages in all those different ways, at the same time that my Mom’s bringing me to theatre productions and my first grade teacher is letting me do forty page stories that she has to edit herself in order for me to see my creativity through (meanwhile by brother’s grade one teacher being so horrid that he still doesn’t pick up a book without shuddering in revulsion). So what about them? Will they be okay, after the age of information chews them up and spits them out the other side?

Of course, this rambling on goes somewhat part and parcel with my age. Pretty soon I’ll be the man in the rocking chair, horrified (like Webster) at what the state of the world has become.

But then again, what’s said and taught to kids matters, it matters perhaps a little more than anything else. Some of the most attentive and critical minds of the early modern era understood that (none, of course, more so than Locke). And they set to work on these impressionable minds and transformed America. Whether it was in the move from a colony to a republic, a republic to a nation, or a Puritan colony to a bustling capitalist economy, these children’s textbooks were there from the get-go, charting that evolution like some kind of primitive-fortune teller. And in 2015, maybe understanding those roots, and everything that grew out of it, is more important now than ever before.

Works Cited

Brown, Gillian. The Consent of the Governed: The Lockean Legacy in Early American Culture. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2001. Print

Ellis, Joseph. After the Revolution: Profiles of Early American Culture. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1979. Print

Rosenbach, A.S.W. Early American Children’s Books. New York: Dover Publications, 1933. Print

Roberts, “Kyle R. Rethinking The New-England Primer”. The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, Vol. 104, No. 4 (December 2010), pp. 489-523. Web

Schnorbus, Stephanie. “Calvin and Locke: Deuling Epistemologies in the New England Primer, 1720-1790.” Early American Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, Volume 8, Number 2, Spring 2010, pp. 250-287. Web

Thomas, Isaiah. A Little pretty pocket-book, intended for the instruction and amusement of little Master Tommy, and pretty Miss Polly. With two letters from Jack the giant-killer; as also a ball and pincushion; the use of which will infallibly make Tommy a good boy, and Polly a good girl. To which is added, A little song-book, being a new attempt to teach children the use of the English alphabet, by way of diversion. Worcester: 1787. Print

Webster, Noah. An American selection of lessons in reading and speaking, calculated to improve the minds and refine the taste of youth. To which are prefixed rules in elocution and directions for expressing the principal passions of the mind. Being the third part of a grammatical institute of the English language. Hartford: Hudson and Goodwin, 1802. Print

The New England primer : containing the Assembly’s Catechism, the account of the burning of John Rogers, a dialogue between Christ, a youth and the Devil, and various other useful and instructive matter : adorned with cuts, with a historical introduction. Worcester : S. A. Howland, 1723

The United States pictorial school primer, designed as a child's first book. Philadelphia, 18?, Print