Course:ENGL211/Deconstruction

Deconstruction is a critical outlook on the relationship of text to meaning created by Derrida. Derrida took inspiration from Ferdinand de Saussure and structuralism. Its aim is not to destroy. Rather, deconstruction is "always a double movement of simultaneous affirmation and undoing."[1]

Origins and Influences

Jacques Derrida

Derrida was a French philosopher, born in Algeria to a Jewish family.[2] He is best known for developing the critical strategy of deconstruction and is seen as one of the major figures of post-structuralism and postmodern philosophy. [3]

Academic Career

In 1952, Derrida attended the École Normale Supérieure, where he met Louis Althusser and completed his master's degree in philosophy on Husserl. He also studied at Harvard from 1956-1957. Three years later, he taught philosophy at the Sorbonne for four years, and proceeded to collect honorary degrees from many schools around the world.

He co-founded and was elected the first president of Collège international de philosophie, an institution intended for philosophical research that could not be completed elsewhere.

Derrida taught at University of California, Irvine, until shortly before his death.

Structuralism

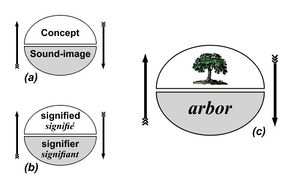

Deconstruction takes inspiration from structuralism and the ideas of Ferdinand de Saussure, in particular his theories of language as systems of signs and of meaning as derived from differences between those signs. [4]

High deconstruction

Roland Barthes

Barthes was a French literary theorist, philosopher, linguist, critic, and semiotician who began his criticism with a structuralist perspective. Helater shifted to a post-structuralist one with the rise of Derrida’s deconstructionist movement.

Paul de Man

Paul Adolph Michel de Man was a Belgian born literary critic & theorist and was considered as a member of the Yale school of Deconstruction. He completed his Ph.D. at Harvard University, then taught at Cornell University, Johns Hopkins University and the University of Zurich. In 1966, de Man attended a conference held at Johns University where Derrida delivered his celebrated essay "Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences".

Key Ideas and Definitions of Terms

Deconstruction

According to Derrida, deconstruction is not a method, critique, or analysis (in the traditional sense of taking a piece of work and finding units of meaning.) Deconstruction is grounded in the idea that "the written signifier is always technical and representative [and] has no constitutive meaning." [5]

Although Derrida was reluctant to elaborate on a definition of the term, others have made their own suggestions. Paul de Man has said that "[i]t's possible, within text, to frame a question or undo assertions made in the text, by means of elements which are in the text, which frequently would be precisely structures that play off the rhetorical against grammatical elements". [6]

Niall Lucy, an Australian writer and deconstructionist, has provided an alternative “definition” for what deconstruction is. He says that ”while in a sense it is impossibly difficult to define, the impossibility has less to do with the adoption of a position or the assertion of a choice on deconstruction's part than with the impossibility of every 'is' as such. Deconstruction begins, as it were, from a refusal of the authority or determining power of every 'is', or simply from a refusal of authority in general. While such refusal may indeed count as a position, it is not the case that deconstruction holds this as a sort of 'preference’”.

The notion that deconstruction undoes concreteness, understanding, and provokes more questions than answers is famously depicted in Henry Melville’s short story “Bartleby, the Scrivener”. Bartleby, the mysterious office worker whose response to every question is a variation of “I would prefer not to”[7], embodies the function of deconstructive interpretation in a text.

In Melville’s story, the elusive Bartleby cracks into the predictable, mechanic, highly structured office environment, which relies heavily on spoken and written language to convey meaning. While the other employees at the office possess distinctive personality traits and behavioural patterns, little is known about Bartleby’s true intentions. His repetition of the word “prefer” only increases the ambiguity in the story and leaves the reader feeling unsettled and likely confused. As the story progresses, Bartleby’s answer remains consistently the same, but the interpretation of it changes as the narrator and the reader find themselves in different contexts. The “I would prefer not to” phrase may seem like an insolent statement one moment, but under different circumstances, it could indicate that there is a different task Bartleby would rather attend to. Because of this uncertainty, the reader never gets a firm grasp of who Bartleby is. The title character, contrary to the readers expectations, is the paridoxically absent centre of the story, one who cannot be fleshed out.

Deconstruction, and Bartleby, can also be explained in the following analogy of a spoon in a glass of water. The critic uses the spoon, deconstruction, to stir the water, the text, to create a whirlpool. Even after the removal of the spoon, the effects of the stirring motion are still visible. The centre of the whirlpool is really a hole, and is the representation of the absence of meaning. In this scenario, the critic is not focusing on how quickly the funnel collapses or how to close up the "hole"; the movements, the swirling around the void is where interest lies. In short, deconstruction is a philosophy that “stirs up trouble" both in the text and in the process of reading. Every time the critic disturbs the water's surface, a different image is produced and increases the possibilities for interpretation.

Différance

Différance is "the observation that the meanings of words come from their synchronity with other words within the language and their diachronic between contemporary and historical definitions of a word". [8] The concept of différance is the absent center of deconstruction, as différance is the inevitable and never-ending gap between signifiers and signified that keeps all meanings unstable.[9]

Double reading

A double reading is a two-stage reading that deconstruction interpretation frequently follows.[10]

In the first stage of a double reading, the reader provides a seemingly stable interpretation with a singular meaning and no deconstruction. It is often an interpretation that a structuralist critic might propose. In the second stage, the deconstructionist critic undermines this seemingly stable interpretation and reveals the multiplicity of meanings. However, the first reading cannot be an unconfident interpretation. [11] It must be a reading that presents what appears to be a convincingly stable interpretation.

The purpose of the double reading is to open an avenue of exploration in a pluralistic Text. Derrida asserts that "The Text is not a co-existene of meaning but a passage, an overdressing; thus it answers not to an interpretation, even a liberal one, but to an explosion, a dissemination" [12]

Multiple meanings

Deconstruction argues that meanings that seem singular or stable give way to a play on language that reveals multiple meanings. [13] These multiple meanings appear in the second stage of double reading, where it is revealed that "[t]here is not a single signified that escapes, even if recaptured, the play of signifying references that constitute language" [14]

Trace

Since the meaning of a sign comes from its differences from other signs, the sign contains traces of what it does not mean. The trace is the meaning that is brought to mind along with the meaning of the word. For example, if a text features masculine characters, a deconstructionist might begin by questioning the exclusion of women.

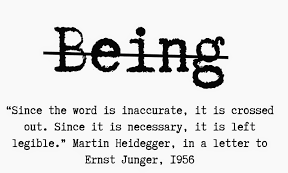

Sous nature (Under erasure)

The concept of erasure or bracketing is a philosophical device that was first developed by Martin Heidegger [15] and was used by Derrida. To put a word under erasure, the writer would cross it out usually with an "X" to signify that the term is provisional [16]. Derrida put words under erasure to show that while he must use the word to explain a concept, he does not endorse it as a representations of a concrete or stable concept. The image on the right is an example of putting a word under erasure.[17]

Logocentrism

Speech is centre of language, not writing as is presumably thought. "The voice is the closest to the signified" [18], whereas writing is only representative. Writing requires the individual to filter thought through the hand and on to the paper, rendering the written medium more manufactured than speech, which is a direct projection of thought from the interior of the mind outwards.

References

- ↑ www.iep.utm.edu/deconst/

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jacques_Derrida#Life

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jacques_Derrida

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deconstruction

- ↑ Derrida, "The End of the Book and the Beginning of Writing" in Critical Theory: A Reader for Literary and Cultural Studies. Ed. Robert Dale Parker. p.102.

- ↑ De Man, in Moynihan 1986, p. 156.

- ↑ Melville, "40 Short Stories: A Portable Anthology". Ed. Beverly Lawn, pg. 29

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deconstruction#Diff.C3.A9rance

- ↑ Parker, in How to Interpret Literature, p. 95.

- ↑ Parker, in How to Interpret Literature, p. 89.

- ↑ Parker, in How to Interpret Literature, p. 89.

- ↑ "From Work to Text" Barthes, p. 117

- ↑ Parker, in How to Interpret Literature, p. 85.

- ↑ Derrida, "The End of the Book and the Beginning of Writing" in Critical Theory: A Reader for Literary and Cultural Studies. Ed. Robert Dale Parker. p. 99

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sous_rature

- ↑ Parker "How to Interpret Literature" pg. 91

- ↑ from Gayatri Spivak, Translator's Preface to Of Grammatology

- ↑ Derrida, "The End of the Book and the Beginning of Writing" in Critical Theory: A Reader for Literary and Cultural Studies. Ed. Robert Dale Parker. p. 102