Course:ECON371/UBCO2009WT1/GROUP6/Article5

Group 6: Carbon Tax in Canada

Article 5: Costly push for carbon neutrality comes at time of penny pinching for schools

Cited Reading:

- CCPA - Is BC's Carbon Tax Fair?

- Suzuki Foundation - Pricing Carbon, Saving Green

- Canadian Government - Taxation and Economic Efficiency: Results from a Canadian CGE Model. Finance Canada Working Paper (Enter Email Address To Receive)

Summary

Last spring all 60 school districts in British Columbia signed the Climate Action Charter promising to become carbon-neutral by 2010. To help schools make better decisions on how to reduce emissions, the Charter requires intensive measuring and reporting, and the province is proposing that this be accomplished through the utilization of a computer software program called SmartTool. School districts are complaining, though, as the SmartTool contract costs 82 cents per student to use the program; in Vancouver alone the cost is being estimated to be as much as $45,000. This programs implementation is at a time when school district budgets are simultaneously being slashed by the provincial government. School officials also question the efficiency of the program in the level of extensive detail required and also its high administrative costs. In response to these problems, some districts have decided against the program and opted to find less costly means of measuring emissions, knowing that eventually SmartTool will most likely be forced upon them.

To become carbon neutral, school districts will also be further required to purchase carbon offsets; and to help, the provincial government will refund what districts spend on the carbon tax on gasoline. It is suggested, however, that the refund will fall short of what is needed to purchase offsets, furthering the financial hardship on school districts.

Analysis

Introduction

This article in the Vancouver Sun brings up an important current issue with the carbon tax and that is how to recycle the revenue generated from the tax. It was reported that school districts will be refunded the money they spent on the carbon tax on gasoline to purchase offsets to help achieve public sector carbon neutrality by 2010. In analying this concept of using carbon tax revenue to aid in the offsetting of other emissions two papers will be referenced as informational aids and a third just for a minor but important contribution. The first paper is from the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA) titled, Is BC's Carbon Tax Fair? and will be referred to as the CCPA paper and the second is from the David Suzuki Foundation it's titled, Pricing Carbon, Saving Green; this paper will be referred to as the Suzuki paper. The third is a working paper fom the federal government titled, Taxation and Economic Efficiency: Results from a Canadian CGE Model, and due to its authors will be referred to as the B.& B. paper.

The analysis will begin by looking at the current situation in British Columbia of the carbon tax being revenue neutral, including the double dividend hypotheses and any problems of fairness that may arise, and then will proceed to evaluate different methods of revenue recycling, methods similar to the one envisioned in the article. It will conclude with the finding that using carbon tax revenue for offsets for school districts can be cost-effective, but in the current context might possibly harm the education system.

The Double Dividend

A carbon tax puts a price on emissions. It is a market-based incentive policy that allows individual emitters to cordinate their polutting behaviour with economic outcomes. Also known as a type of Pigovian tax, by levying a charge equal to the negative externality of pollution, it seeks to internalize the true marginal cost into the market.

In BC the carbon tax is revenue neutral, it was implemented with the decision that all revenue taken in from the tax would be used to fund other tax cuts, in particular cuts to the income tax. Such revenue neutral applications of the carbon tax have been theorized to produce a double dividend. It should be noted that nn cases where negative externalities are present, the existence of a tax can actually increase economic efficiency. Now the first dividend, results from the reduction in emissions (a lessening of the damage caused by the negative externality and a move toward the socially efficient level of emissions) which increases environmental benefit. The second dividend results from the use of carbon tax revenue to decrease other more harmful taxes; this decrease reduces the excess burden or deadweight loss of those other taxes, and increases net social benefit by providing gains in economic efficiency.

The Suzuki paper differentiates between two kinds of double dividend hypotheses, strong dividends and weak dividends. Both types result from a carbon tax that reduces emissions and decreases deadweight losses caused by other harmful taxes; however the strong dividend actually produces a net economic gain, making the economy on the whole better off with the carbon tax. On the other hand, when using revenue from a carbon tax to lower other taxes, if the prevented deadweight loss does not make up for the damage caused by the carbon tax, it is said to result in a weak dividend. It is important to note though, that even with a weak dividend, at least some economic inefficiency that would otherwise take place is reduced. This point seems to be neglected in the CCPA paper.

Revenue Neutrality and the Fairness of BC's Carbon Tax Questioned

The double dividend arises from revenue neutrality, however as stated in the Vancouver Sun article, at least in regard to school district expenditures on gasoline, the carbon tax's revenue will no longer be used to reduce income tax, it will be used instead to aid schools in purchasing carbon offsets. In its report the CCPA argues against revenue neutrality and can be cautiously interpreted as providing support for the BC government's alternative use of carbon tax revenue for school districts.

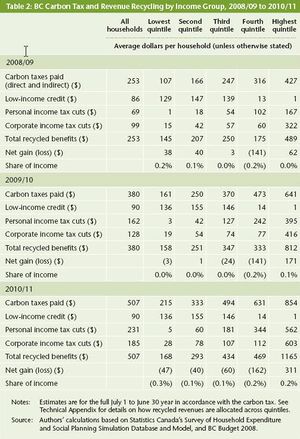

The Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives in its report divided BC residents by income into quintiles and calculated the cost and benefits of the carbon tax for each year of its tax increases. Table 2 (See right) describes the reports findings; it illustrates that only in the first year is the tax progressive to the lower quintiles, afterwards it is shown to be regressive. In 2009/10 the carbon tax increases for the lower quintiles more than their corresponding income taxes decrease, this occurs while the carbon tax performs the opposite operation for the highest quintile. The tax incidence proportionately falls more on those of lower incomes.

From its findings, the CCPA argues that lower income earners deserve a larger decrease in income tax, not only because they have a smaller carbon footprint than higher income earners, but so they can have equal opportunities to invest in green technologies and innovations in order to reduce their emissions. The CCPA goes even further and argues against revenue neutrality. The CCPA paper suggests first, that there is little reason to believe that a double dividend for carbon tax exists and second, that the BC provincial government's decision for the carbon tax to be revenue neutral was but a mere political one. Instead the CCPA plead that the revenue from the carbon tax should only go to income tax cuts for the lower income British Columbians and to building transportation infrastructure, investing in green technologies, and aiding in energy efficiency.

The CCPA report makes no mention of purchasing offsets as a preferred alternative to revenue neutrality; however it does make reference to the idea that the public sector should be made more energy efficient. On page 21 of the CCPA paper it states:

There is a risk that public services will be undermined by environmental objectives. This should be addressed by recycling some of the revenues back to public sector entities, but more importantly, launching a major capital campaign to improve energy efficiency and reduce the carbon footprint of those entities, making them less financially vulnerable to rises in the carbon tax.

Requiring school districts to offset their emissions would be a more decentralized method of motivating them to become energy efficient. However as the above quotation noted, in requiring offsets the provincial government runs the risk of subjugating the quality of education to the quality of the environment.

Though there is a potential threat to the quality of education in having school districts divert funds to purchase offsets for their emissions, the longterm benefits of energy efficiency may prove to outweigh any risk. The CCPA paper points out such risk, but also highlights the importance of energy efficiency in the public sector. The BC government's plan however has not evaded criticism just yet, for though the CCPA paper offers support for similar alternatives to revenue neutrality, there is evidence to suggest some alternatives may not to be preferred.

Reuse, Recycle, and, Unfortunately, Reduce Revenue

Pricing Carbon, Saving Green analyzes revenue neutral methods of dealing with carbon tax revenue as well as some alternatives similar to the ideas proposed by the CCPA report. The six options that are evaluated are:

- Recycling to reduce personal income tax

- Recycling to reduce payroll taxes

- Recycling to subsidize economic output

- Recycling using lump sum rebates for households

- Recycling to subsidize low-emission technologies, subsidize economic output, and reduce payroll taxes

- Recycling to subsidize residential energy efficiency and renewable energy, and reduce payroll taxes

The first four of these options are revenue neutral in the sense that the money the government collects from the tax is returned in kind to the tax payers. The last two options are not revenue neutral and involve using at least portions of the carbon tax revenue to invest in green technologies, energy efficiency and renewable energy; these two options are similar to the CCPA proposal and the current BC government strategy for school districts.

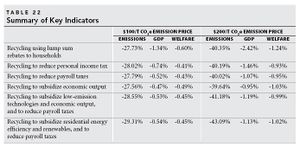

Table 22 (See right) lists the six options analyzed and compares their effects on emissions, GDP, and welfare with the price on a tonne of CO2e being $100 or $200. It is of interest to look at the four revenue neutral options and their effects on GDP, as none produce a net gain, and therefore possibly provide evidence that there is no strong double dividend, at least with these prices. In comparing all the options it is clear some are to be preferred over others. For instance lump sum rebates to households is the worst option, having one of the lowest effects on reducing emissions and the worst effect on welfare and GDP. Though it remains unclear which option is to be the most preferred, the last two options do seem to fare quite well. In fact other than a very small difference in effects on welfare, the last two options, both of which are not revenue neutral seem to perform better than the current revenue neutral carbon tax which has its revenue recycled through income tax cuts.

Acknowledging the problem of extrapolation, a comparison can at least be presented for consideration, and that is that the BC government's plan of recycling carbon tax revenue to subsidize school districts purchases of offsets could be seen as falling somewhere within the last two options. As having school districts required to purchase offsets, they are given an incentive to find ways to reduce their emissions, and to achieve reductions green technologies, energy efficiency, and perhaps even renewable energy may be adopted. With more certainty however Table 22 of the Suzuki paper seems to justify the CCPA's proposal of abandoning revenue neutrality and instead investing in cleaner innovations.

Revenue Neutrality, Double Dividend, And Capital Taxes

Though both the CCPA and the Suzuki papers come to conclusions that cast doubt on the benefits of having a carbon tax that is revenue neutral, there is an option that is revenue neutral that may just have such a strong double dividend effect that it would be greatly preferred.

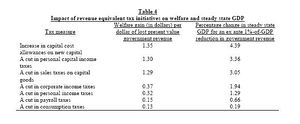

In discussing the double dividend hypotheses the Suzuki paper touches upon evidence that suggests that the capital tax is perhaps the most distortionary of taxes. This is of importance, because the larger the distortion created by the capital tax, the greater the benefit incurred when that tax is reduced. Thus if the capital tax was so distortionary that a small reduction would create large benefit, carbon tax revenue could be used to offset the capital tax and actually provide a net gain.

Table 4 (See right) from the B & B paper lists a variety of taxes and their corresponding effect on general welfare for every dollar they were reduced. Near the top of the list, one dollar in a cut in personal capital income taxes is shown to render a $1.30 in welfare. This is startling when one compares that amount to the amount of welfare generated from a cut in personal income taxes or payroll taxes, where one dollar of revenue reduced only provides $0.32 and $0.15 respectively. According to this table the capital income tax is four times as distortionary as income taxes and 12 times as distortionary as payroll taxes. In reviewing Table 22 of the suzuki paper, if such a relationship held, it could be possible that using carbon tax revenue to offset capital income taxes would produce a net gain.

The Suzuki paper however rebuffed such an idea. While not denying the possibility of a strong double dividend when capital income taxes are cut with carbon tax revenue, the paper suggests that more research was needed. Perhaps though a bigger problem is that the capital income tax is paid by those of higher incomes, and since carbon tax revenue would be used to offset a cut in capital income tax, the beneifts would would most likely be conferred upon the wealthier, making the policy almost impossible politically to implement.

Conclusion

In summation evidence suggests that as the carbon tax exists now, lower income earners are bearing more of the tax incidence, thus suggesting changes are needed. In addition it is also seen that there could potentially be greater economic benefit if the carbon tax was not revenue neutral and instead had its revenue recycled to subsidize transportation infrastructure, cleaner technologies, and energy efficiency programs.

In context of the recent situation reported by the Vancouver Sun concerning school districts and offsets, though offering an incentive for public sector entities to become carbon neutral enables possible economic gains, it is unclear whether the risk of lowering the quality of education is worth requiring school districts to divert funds to purchase offsets, to use SmartTool, and to increase administrative capacity. The recycling of carbon tax revenue to subsidize school districts to purchase offsets is a decentralized policy, that allows the relative individual bodies to find what's best for them, but as noted, in the process the educational services they provide may be negatively affected.

SmartTool and the totality of the emission recording program does present an informational opportunity that could increase energy efficiency. The article notes that Education Minister Margret MacDiarmid is of the position that SmartTool is valuable in seeing where improvements need to be made to decrease carbon emissions; however, due to macroeconomic conditions, some education administrators believe this will only be an unnecessary use of already limited resources.

In facing this situation where there is a possible short-term tradeoff between the quality of education provided by the provincial government and some environmental benefit in terms of energy efficiency, one solution could be offered to protect against unintended harmful consequences. If some form of measurement on the quality of education were instituted, school districts could still be required to purchase offsets, but with monitoring of the level of education provided, any degradation on the learning process could be mitigated or even prevented. Granted this monitoring would incur its own additional costs and could potentially stress school district budgets even further if they were to pay for their own monitoring, but in a society where education and the environment are of such great importance, it might prove necessary to ensure the improvement of one does not cause harm to the other.

It would seem prudent to investigate the benefits of measuring educational quality to ensure that the cost to society from any impact does not outweigh the benefits gained from diverting money directly spent on education to measuring emissions and purchasing offsets. It may also be difficult to detail such a form of measurement on the quality of education, but certainly not out of the realm of possibilites for economists.

Prof's Comments

Nice job on going beyond the article. I think you could have discussed a bit more of the article itself though, as you seem to have used it more as a jumping off point to the issue of double dividend.