Course:CONS370/2019/ Title and land rights of the Guarani peoples of Paraguay and Bolivia, South America.

The Guarani people are a group of South American Indigenous people who live in the subtropical forests of Paraguay and Bolivia[1]. The Guarani People’s culture, livelihoods and theology are deeply rooted in the forest and they consider themselves a part of the forest, rather than just users or inhabitants of the forest[2]. The Guarani people have been in contact with modern society since Spanish explorers travelled to South America in the 16th century[1]. Although initially allies with the Spanish, over time more outsiders infiltrated the forest in search of exploitable resources such as timber or oil; this created socio-economic changes to the Guarani way of life[3][1][4].

Bolivia and Paraguay both have strong legal obligations under Constitutional decrees and ratified international laws, that on paper, give Indigenous Peoples additional cultural rights and ownership to ancestral land[5][6]. However, in practice, Guarani view compliance with this framework as flawed and still face high levels of discrimination and exclusion from economic and political spheres[7]. In this wiki page we discuss the complexity of the Guarani peoples' forest-based theology and their roles and relationships in modern land tenure regimes in an urbanized world in the face of large scale development[1][5].

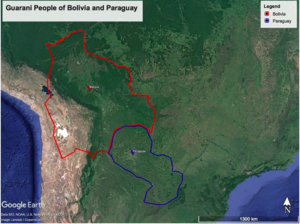

Location

The Guaraní People of South America can be found in Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, Bolivia and Paraguay, but this wiki page focuses on the tribes living in the Chaco lowland regions of South America in Bolivia and Paraguay (Figure 1) [8][9]. Within this region the Guaraní form the Tupi-Guaraní group which is further split into local groups that have distinct cultural and linguistic differences[1]. The Paraguayan Guaraní live in over 300 communities [1], while communities in Bolivia are made up of around 600 families [7], all of which are made up of different numbers of kin groups that comprise a village with its unique cultural identity[1]. Some of the descendants of the Guarani people within these communities who intermarried with Europeans are called mestizos or criollos and still live within the historic indigenous ranges [1].

History

Pre-reforms:

In the early history of South America Indigenous people in many countries including Bolivia and Paraguay lacked formally recognised property rights and land was controlled as de facto as communal lands[6]. Households could be granted individual rights to cultivate small plots, but in essence the forest resources were state owned and controlled by the government [6]. For decades Bolivia and Paraguay both faced problems of privatization of their national forests as a result of government granting long term tenure rights in the form of licences to international corporations [9]. Another prominent problem before the constitutional reforms in Paraguay that created problems for Indigenous land tenure was the notion that the Guarani people were a "threat to security" and relations with the government were all handled by the military[1].

- 1500s: European colonisation first occurred (Europeans intermarried with the Guaraní of the region, producing descendants called mestizos or criollos) [1]. During this century many Guarani died due to introduction of new diseases and the new colonizers forced this Indigenous group to work as labourers [1].

- 1600s: Jesuit and Franciscan missionaries began, converting Guarani people to Christianity/Catholicism and building churches in their territory [1].

- 1700s: Brazilian slavers forced the Guarani People of Brazil and Paraguay to become slaves on sugar plantations[1]. This ended when Paraguay won its freedom from Spain in 1812.

- 1967: Paraguayan Constitution created. Outlined Paraguayan citizens' fundamental rights, but did not address the Guarani peoples' rights. The Constitution allowed the expropriation of not "rationally" used land (this was often ancestral land belonging to indigenous groups).[10]

- 1981: Law 904; Indigenous Communities Statue of Paraguay was passed to recognize legal rights of land to Indigenous groups[5].

Post-reforms (1990s):

Within Latin America with international pressures to recognize human rights, Bolivia and Paraguay began to adopt new reforms within their constitutions that allowed for recognition of the unique rights of their Indigenous populations [5]. The reforms and laws passed in the 1990s began to given legal rights to the Guarani communities and were a stepping stone to gaining rights to ancestral territories [1]. Paraguay also helped to improve relations with its indigenous peoples by moving relations from the military sector to the Ministry of Agriculture and Ranching[1].

- 1987 FUNAI (Federal Indigenous Agency) identified Indigenous land for Guarani in neighbouring Brazil[11]

- 1988 lands in Brazil were recognised and processed as Indigenous with a plan known as demarcation (Guarani tribes could occupy land, but ownership still belonged to Federal government) [11].

- 1989 (Paraguay) Stroessner 's presidency ended and General Andres Rodriguez came into control. This change lead to a wave of land occupations and the creation of Campesino organisations that advocated for land for the landless and investigations of human rights violations[10].

- 1991 (Bolivia) & 1993 (Paraguay) ratified The Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989, No. 169 (also known as ILO 169) [7].

- 1992: Paraguay adopted a new constitution that allowed for the legal allocation of land to Indigenous Groups on lands with ancestral claim[5][12].

- 1992: (Bolivia) formation of Central Organization of Native Guarayos Peoples (COPNAG) to help give political power to Guarani communities[6].

- 1994: Bolivia undergoes constitutional reform to give recognition and give legal right to ancestral territory of Indigenous communities[5]

- 1996: Bolivia formulates the National Agrarian Reform Service (INRA) Law [5]; the tenure reform law recognised Guaraní territory or Community Land of Origin (TCO). INRA law offered rights and decision-making powers to indigenous populations[6]

- 2007: Paraguay voted in favour of United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP)[12].

Pedagogy & Theology

Although Spanish is also spoken in Paraguay and Bolivia, the 1982 census found that Guarani was the primary language spoken in rural households, despite most of the population identifying

as non-indigenous[10]. The Guarani communities are usually made up of 10-25 households that are built into the forest; each household has its own plot of land and garden surrounded by grasses and trees to provide physical privacy among neighbours [1]. Despite this physical privacy, households are all closely tied by kinship, as well as religious and economic networks in the tapyí (community) [1]. Kinship is the basis of internal land rights within the Guarani; although couples usually spend a year with the bride's family after marriage, later on households can choose to establish themselves among any tapyí in which they have close relatives [1].

The Guarani people have accommodated to the national system and become a part of the larger economic market and greater society in general, but still maintain their ethnic and cultural independence[1]. Guarani Pedagogy is described by one member of the Guarani people as an integrated approach that takes into account the cosmos, life cycles, time and universal balances [11]. Another member in Paraguay explains that “We are the forest. It is our life” [2]. The soul is described to have two elements, the human part and the forest part, that comes in animal form that is inherited when the individual is only a child [1] . Within each community (also called tapyí by the Guarani) there is the Paje or shaman (spiritual leader), there are the farmers, women who weave, and elders who sing; every one is a teacher and everyone is a student[11]. There is also a heavy focus on art and dancing, as they believe that through art one becomes more connected to the Earth and the true essence of life [11]. They gather non-timber forest products (NTPs) to be used in their art such as feathers as well as plants to dye these feathers. NTP’s such as plants, citrus oil and special ceremonial wood are used in rituals and medicines as well [11].

Guarani religion sees the world as flat (Yvý) in which the water acts as a barrier between the spiritual realm and the physical world[1]. Their religion and creation stories also largely incorporate cosmology [1][13]. The creation story has four stages in which first the supreme deity Namandú or "Our Great Father", is self-created in a process and imagery that is described represents the forest in which Namandú's arms are the branches, and the fingers are the leaves. The secondary Gods are then made, for example Karai is the master of fire and sun, Jakairá, the master of for and mist, and Tupâis, the master of water and storms. Finally, in the last stage, the land is created[13].

Tenure arrangements

Bolivia:

Within Bolivia all forests were owned by the government but the government grants 4 different type of tenure that give harvesting rights and long-term communal title:

- Forest Concessions: 40 year grants given to large companies involved in the timber industry that are renewable every 5 years[14].

- Local Social Associations (ASL): 40 year grants given to groups of local people that have resided on the land for a minimum of 5 years [14].

- Indigenous Lands (TCO): Granted to Indigenous groups that can prove long term traditional rights to the land[14].

- Private Lands: Purchased or granted for free to individuals or groups[14].

The Guarani Peoples are involved in a communal tenure agreement that involves co-management arrangements of Indigenous communities with the government [6]. The Guarani tenure agreement, titled TCOs (tierra communitar de origen), were created specifically for ethnic and indigenous groups to give legal and secure access and rights to communal private lands [6][14]. To gain this tenure, communities much first prove their traditional and historical rights and use of the forest, after which the government performs a territorial assessment of the potential management unit [6][14]. Once granted, the tenure then becomes “inalienable, indivisible, non-reversible, collective, [non-mortgageable, and tax exempt]”[6], thereby on paper giving the land back to the Guarani Peoples. The bundle of rights within this private tenure arrangement include the right to access, withdraw, manage, and exclude, but does not include the right to alienation and therefore cannot be transferred or leased to other groups for further economic benefits[6].

Paraguay:

The land tenure regime found within Paraguay is less well managed and documented than Bolivia, and because of such, operates in practice as an open-access tenure regime[15]. However on paper legally there are 3 tenure types available:

- Private Lands: Granted to individuals and corporations for access and use for natural resource extraction and cattle ranching[15].

- Protected Areas: Government owned areas varying in use and access restrictions that are dedicated to land protection and may contain groups of individuals relocated for residency[15].

- Indigenous Lands: Granted to Indigenous Groups that can prove ancestral claim to the land[15].

The Guarani people of Paraguay are involved in resource management of their forests for shifting agriculture (ex. Figure 5), hunting & gathering (ex. families rely on meat from the forest such as deer and armadillos) and commercial forestry purposes [1]. Similar to Bolivia, Paraguay offers a land tenure agreement that gives the Guarani rights to communal lands that are inalienable, unmortgageable, and imprescriptible[5]. The bundle of rights held by this group include the right to access and are state protected but they lack the to right to use for commercial purposes (other than for survival), manage, and alienate or lease the land, which is drastically different from the Indigenous Land tenure held by Guarani in Bolivia[15]. Furthermore, Paraguayan law states that indigenous peoples such as the Guarani, can only reclaim ancestral lands if the following conditions apply: (a) it is state-owned land, or (b) the current owners are not making rational use of the land, and (c) the current owners are willing to sell the land to the state [16].

Administrative arrangements

Within Bolivia the institutions and management authorities that oversee the management unit of the TCO are:

- The National Institute of Agrarian Reform (INRA) is a government sector designed to govern decisions on land tenure titles, management unit boundaries, and implementing the agrarian laws of Bolivia [7][6]

- State Forest Superintendents are state appointed officials that control the access, fees, and management plans of the management units within their state [6].

- Regional community organization The Central Organisation of Native Guarayos Peoples (COPNAG), is a group of elected provincial leaders that verify Guarani land claims and protect contested rights of the Indigenous communities [17][6].

- The Community Forestry Management Organization to which the TCO has been granted is made up of Guarani members in charge of decisions regarding management plans on the land[6].

The acquisition of TCO tenure within Bolivia first starts with regaining the rights to their traditional lands and require forming management organizations to gain rights to the management units by providing documentation of their traditional and historical residence in the forest[6]. These claims are submitted to COPNAG along with an inventory and management plan, that then undergo review by the government before they can be validated[6]. Once the lengthy process of validation occurs INRA then demarcates and approves the TCO boundaries [6]. Once they have been granted rights the reporting system of the TCO requires the community organizations to submit their annual management and operating plans to the Forest Superintendents for approval in order to be allowed to harvest[6]. In the case of land disputes the community organization reports disputes to Forest Superintendence, and in the case they are unable to rectify land claims, INRA then investigates [7][6].

Similar to Bolivia, Paraguay has national government agencies that oversee land tenure, but the reporting and granting system is not as organized. The institutions overseeing the indigenous lands in Paraguay are:

- The National Forestry Institute (INFONA) is responsible for dealing with land use plans for land conversion, forest management, and implementation of national forestry laws[15].

- The National Institute for Rural and Land Development (INDERT), formerly the Social Welfare Institute, works with INDI to help determine legal status and claims of Indigenous groups[12].

- The government agency of The National Institute for Indigenous Affairs (INDI) is responsible for issues of land claims and rights to the Indigenous groups of Paraguay [12][15].

- Institute of Rural Wellbeing (IBR) the agrarian reform agency capable of distributing land to marginalized and local communities[5].

To gain rights to land Guarani Peoples must make claims to INDI and IBR to help verify the ancestral claims of the Indigenous groups[18]. Once land rights have been granted, together INDI and INDERT help to monitor and protect the lands and the natural resources, and will rectify any land claim disputes or intrusions[12]. INFONA is then responsible for monitoring and keeping track of the land boundaries and claims in all Paraguayan states[18]. Typically INFONA is also responsible for approving land conversion forest management plans, but since Indigenous lands are intended to be used for subsistence use, management plants are not provided[18].

Affected Stakeholders

Within Paraguay there are 19 different Indigenous Peoples in 5 linguistic families (Guarani, Maskoy, Match Mataguayo, Zambuco, and Guaicurú)[12], while in Bolivia there are 37 Indigenous Peoples belonging to a vast array of linguistic lineages (Guarani, Quechua, Aymara, Chiquitano, Mojeño)[7]. These Indigenous groups are considered to be affected stakeholders within these nation states because they are forest-dependent communities that have developed a long ancestral traditional relationship with the land. In our case study, the Guarani People of both Bolivia and Paraguay are the affected stakeholders within the forests of South America that we focus on. This Indigenous group is affected because they value their forests for more than just its economic benefits but for its inherent intrinsic value and have a strong traditional and historical tie to the land[2]. Their theogony and culture is so strongly rooted in their ancestral lands that they possess a deep connection with the land that makes them feel “one” with the forest[2]. Not only is this group forest-dependent for direct sustenance, they also use it for natural resource extraction through timber harvest to help supplement their sustenance through income generation[4][6].

This group holds low relative power within their traditional forests of Bolivia and Paraguay regardless of the strong legal framework created through ILO 169 ratification and Constitutional reforms that were designed to give more strength to Indigenous groups[5]. Within their respective countries, Guarani hold little power and are subject to lengthy battles for tenure that result in discrimination and inadequate land rights[7][6]. However, because each country has ratified ILO 169, Guarani People hold some power as they are able to attend international platforms to lobby for support for land tenure rights and recognition[7].

Interested Outside Stakeholders

Interested stakeholders are social actors or user groups who play a role in the systems charged with administration of the forests in Bolivia and Paraguay but they, themselves are not dependent on the forest in order to live [19]. Since the Guarani cross political boundaries of South America, each community faces unique interested stakeholders that they interact with and the relative political and economic influence and power of stakeholders varies between Paraguay and Bolivia.

Table 1: Bolivian Interested Stakeholders:

| Stakeholder | Objectives | Relative Power |

|---|---|---|

| National Institute of Agrarian Reform (INRA) | Responsible for dealing with issues surrounding land titles and addresses and evaluates contested claims [6]. Officials in this department are indirectly tied to the forest as a source of income for their salaries. | High level of power |

| State Forest Superintendence (government) | Award timber concessions, approve or reject land claims, control access and collect forest fees[6]. State officials indirectly use the forest as a source of income. | High level of power |

| Regional Organizations(COPNAG) | Advocate for local indigenous communities and represent their forest-related interest as well as help validate Indigenous villages land claims to forest management units [6]. These individuals care about the land for its economic benefits as well as for providing social equality for the Guarani in Bolivia. | Limited power (Medium) since they can not fully control decisions made by gov. agencies. |

| Industry (ex. agro-industries, timber etc.) | Large scale commodity production (ex. soybean), cattle ranching, or timber harvesting are the main objectives[6]. Companies are economically driven to use the forest for land conversion and resource extraction. | High level of economic and influential political power |

| International and Local NGO's | To gain management rights, indigenous communities in the Guarayos TCO had to seek assistance from NGOs that provided technical support and subsidised the costs of creating management plans [6]. Many NGOs are also interested in preserving and enhancing biological and social diversity of the Paraguayan and Bolivian lowlands [20]. | Limited power (Medium power) |

| Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) | Independent, international organization that promotes the sustainability of forest harvesting that is socially, economically, and environmentally sound [17]. Forest concessionaires must pay fees/taxes and acquire FSC certification by meeting FSC standards [21]. As of 2015, 890,529 ha of land was certified (total of 11 certifications)[21]. Members of this organization indirectly use the forest for income as well has have a high degree of care for the well being of the forest. | Medium-High power |

| Inter-American Court of Human Rights | Deals with Indigenous rights cases and supports the principles outlined in the United Nations 2007 Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples[16]. This organization is tied to the forest indirectly by providing assistance to local individuals that face human rights violations against them by their national government [7]. | High Power. |

| Smallholder farmers (non-indigenous) | These are non-indigenous individuals who are often a mix of different ethnicities whose livelihoods are forest-dependent[8]. These individuals use the forest as a source of income and to supplement sustenance. | Low power (need policies and land tenure in order to improve access to natural capital in forest that their livelihoods depend upon)[22] |

Table 2: Paraguayan Interested Stakeholders:

| Stakeholder | Objectives | Relative Power |

|---|---|---|

| The National Institute for Rural and Land Development (INDERT) | The government agency working above INDI in the government hierarchy that is responsible for the process of returning land and land title[12]. Individuals in this agency use the forest indirectly as a source of income generation for their salaries. | High political and economic power |

| INDI (Paraguayan Indigenous Institute) | The government agency also responsible for issues of land claims and rights to the Indigenous groups. This department cares about the forest for its economic benefits as well as for providing the Guarani with social equality in their ancestral lands[12]. | Medium-High power |

| Institute of Rural Wellbeing (IBR),

and Paraguayan Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock |

The central government agencies responsible for mandates to plan colonization programs, issue land titles to farmers, and provide support services to rural communities such for markets, roads, and other social services [5][1]. These members indirectly use the forest for a source of economic benefit and also have a relatively high degree of care for the biodiversity and social welfare of the forests. | High political and economic power |

| Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) | Independent, international organization that promotes the sustainability of forest harvesting that is socially, economically, and environmentally sound [17]. Forest concessionaires must pay fees/taxes and acquire FSC certification by meeting FSC standards [21]. As of 2015, 890,529 ha of land was certified (total of 11 certifications)[21]. Members of this organization indirectly use the forest for income as well has have a high degree of care for the well being of the forest. | Medium-High power. |

| Inter-American Court of Human Rights | Deals with Indigenous rights cases and supports the principles outlined in the United Nations 2007 Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples[16]. This organization is tied to the forest indirectly by providing assistance to local individuals that face human rights violations against them by their national government[7]. | High Power. |

| International and local NGO's

(ex. Fundación Moisés Bertoni (FMB) a Paraguayan NGO, Survival International and WFF (international NGO's). |

Organizations that work in partnership to protect the voices and rights of Indigenous and tribal people of Paraguay, while also managing for conservation objectives[23][20]. | Limited power (Moderate) |

| Multinational companies/ enterprises (ex. Cargill, ADM and Bunge) | Large corporations that mostly own large-scale soy bean plantations, but also conduct other natural resource extraction and land conversion practices[15]. These companies are driven by market demand, with the main objective being wealth and economic benefit. [24] | High economic and influential political power. |

| Smallholder farmers (non-indigenous) | These are non-indigenous individuals who are often a mix of different ethnicities whose livelihoods are forest-dependent[8]. These individuals use the forest as a source of income and to supplement sustenance. | Low power (need policies and land tenure in order to improve access to natural capital in forest that their livelihoods depend upon)[22] |

Discussion

Both Bolivia and Paraguay are countries that on paper have a good legal framework to allow for land rights of Guarani People to be recognised and enforced[5]. Both countries have made good progress of incorporating Indigenous rights into their constitutions through reforms in the 90's that legally recognized Indigenous ancestral claims to land[5]. It is evident in Paraguay that Guarani rights to land in theory are protected through many National laws (i.e.: Indigenous Communities Statue, Law 904, 1981), International law ratification (ILO 169) and in the Paraguayan Constitution (Article 64), but in practice it has proven to be a different story[5][12]. The same situation for Guarani is present within Bolivia where similarly, International law ratification (ILO 169), Constitutional reforms, and National laws (Forestry Law of 1996) have set legal framework for Guarani to gain legal rights to their ancestral lands that have been found to be flawed and unsuccessful in practice[14][5].

The common success of the legal frameworks in these countries for the Guarani people is the willingness of the National Governments to adopt Constitutional changes and ratify International laws that acknowledge the additional rights these groups possess. However, the application and monitoring of these legal frameworks is where the system begins to degrade. Partially due to inadequate tenure systems, many countries in South America, including Bolivia and Paraguay, experience high levels of land grabbing through coercion, violence, and lack of protection from the government[18]. Within Bolivia and Paraguay, even though Guarani people and other Indigenous groups make up a substantial portion of the population, there are still high levels of racism and discrimination that leave them alienated from society and reduce their political and economic power[7][12]. To help increase the political power of marginalized indigenous groups there have been rallies held within both countries to incorporate Indigenous departments within their governments[9]. These demonstrations historically have proven to be successful and the government organizations of COPNAG and INDI within Bolivia and Paraguay respectively, have given a voice to the Guarani, and have made progress in considering the rights of indigenous groups [9].

Some of the common downfalls of these systems are the governments' lack of restriction and protection of Indigenous lands from illegal access, slow titling and land dispute monitoring process, prioritization of titling being given to large forest concessions, and lands given are fragmented small parcels that do not encompass the entire ancestral land[12][5][6][9]. Historically a large problem these countries face is the reclamation of land back from large multinational organizations that have caused a form of privatization of the land and do not wish to give up tenure rights[5]. Therefore, although the national governments have set up a strong legal framework for returning land rights to the Guarani, they have overlooked how they will regain access to these lands to allow for redistribution to the traditional tenants[5]. Within Paraguay, the major problem lies in regaining land back from large international forest concessions that do not wish to renounce their tenure rights to the land[12][5]. In Paraguayan law the private land owner must be willing to sell land back but INRI in recent years has had funding cuts and therefore finding funds to reclaim land for the Guarani has been difficult[16][5]. To try and rectify this problem many local NGO’s, such as the Fundación Moisés Bertoni (FMB), have be founded to work with Guarani communities to provide financial and political support to regain tenure rights to ancestral land[20]. These NGO’s have proven to be successful since they have allowed for land reclamation and have established a strong local-global collaboration to increase economic and political power[20].

Both countries are also ignoring the Guarani traditional institutions and values, and are imposing their countries' management practices onto these communities. Within Bolivia the TCO is constrained to municipal boundaries but many communities do not conform to these political borders. To rectify this Bolivia has has allowed for Guarani to form Indigenous Municipal Districts (DMI) to allow for cross municipal management, but this system does not allow for finances to be shared in the communal cultural way and are subject to legal restrictions on sharing the wealth[9]. The framework that was created did not take into consideration the values and customs of the Guarani Peoples and has proven to be troublesome in implementation for these communities that lack knowledge of their nation's legal and economic systems[6][9]. Within Bolivia the solution for this problem has been to move away from the creation of DMI groups and to incorporate NGOs in these initiatives to remove the restrictions on communal sharing that has began to allow for customary ways of living within these communities [9].

Power Analysis

The major interested stakeholders involved in the title and land rights of forested areas of the Guarani people (affected stakeholder) are described in Table 1 and Table 2 above. Each stakeholder has various levels of care and power. For example the Guarani people have a high level of care for the forest and land, but due to a long history of colonialism and oppression, are left with the lowest degree of power in both Paraguay and Bolivia [12][7]. Although the Guarani and small-holder farmers have the lowest level of power in both countries, as discussed above, some of this power is slowly being returned through the ratification of international laws and the titling of land back to indigenous peoples (including the Guarani) by the state [25][5][12]. For example, in Paraguay almost two-thirds of the recognized Guarani communities now have title to some of their ancestral land, and this proportion continues to rise[1]. In contrast to the Guarani, the state has the highest level of power because although companies, international NGO's, and the public may influence or push for decisions, it is ultimately the state that makes the final determination of who gets land returned and in what location[16]. Within government there is a hierarchy of agencies involved in Indigenous rights in which INDERT is above INDI (table 2)[12]. This multi-level system makes coordination and communication among agencies difficult and Indigenous rights often suffer because of this; if INDI were awarded a higher level of power by becoming the Ministry for Indigenous Peoples, it would result in more transparency in roles and efficient funding[12]. It is important to note that in Bolivia and Paraguay the Inter-American Court of Human rights has the power and jurisdiction to order the government to return ancestral land to the Indigenous or tribal peoples [16]. The Inter-American Court of Human rights would be an example of an interested stakeholder with both high levels of care and power.

In both Paraguay and Bolivia, international corporations and investors involved in the large-scale commodity production have a high level of power because they hold so much wealth. That being said, money and production are their main objectives, and Indigenous land rights, forest health and ecosystem integrity often come secondary[9]. For example, in 1984 foreign investors caused conflicts due to developing a forested area in Paraguay inhabited by communities of Mbyá-Guaraní [1]. The government proposed a 400,000 hectares development project called Proyecto Caazapa, that would be funded by the World Bank. That was an example of the dismissal of Guarani land rights and consultation that lead to the destruction of Guarani forests for the construction 400 km of roads[1]. This case study displays how much power and influence international investors have on the actions that occur on the ground in Bolivia and Paraguay[1]. Private and public NGO's attempt to use their moderate level of power to resolve this injustice, through partnering with Guarani communities to protect their voices and help support their small-scale agriculture and forestry activities. These include both international and local NGO's such as FMB, World Wildlife Foundation (WWF) and Survival International [20]. Although these organizations have well-educated and caring staff, they have less power because most of their funding relies on donations from the public and is therefore limited[1]. In conclusion through this power analysis it has become apparent that similar to other developing countries those that care the most about the land are also those with the least amount of power to manage it[22]. In the next section we will discuss our recommendations surrounding the ingrained power inequality occurring on the ancestral land of the Guarani people.

Recommendations

The struggle for land tenure acknowledgement and equality of the Guarani People of Bolivia and Paraguay is a similar situation that many other Indigenous Groups of Latin America have found themselves in. Since the 1980s there has been a global trend for more democratic frameworks as well as democratic decentralization that shifts power and resources from federal departments to local municipalities that tend to be more accountable to the local peoples[6]. Our recommendations for this case study is a continued push for devolution of land rights to the Guarani themselves as well as the implementation and adoption of guidelines to aid in proper tenure restoration and monitoring of the Guarani land rights. We believe that by creating local organizations to deal with Guarani land claims this will remove the problems of inconsistencies in regional and national government agencies that lack a cohesive framework that increases inequality of small communities. To try and achieve this, in 2012 the United Nations Committee for Food Security created the Voluntary Guidelines on Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries, and Forests (TGs) to protect, promote and restore tenure rights to marginalized local stakeholders, that we believe outline the framework necessary to achieve a successful tenure regime[18]. Both Paraguay and Bolivia in 2015 at the Special Meeting on Family Farming (REAF) agreed to implement TGs into their tenure reforms and have made progress in rectifying legal shortcomings[18]. For these community forest projects our recommendation is that both state governments follow through and use these guidelines as a means of identifying the problems within their legal frameworks. Since both countries have a strong legal framework for promoting human and tenure rights to Guarani the purpose of TGs would be to help increase the ability of state agencies to follow a set guideline of how to deal with issues of overlapping tenure disputes and how to restore land to Guarani communities [18].

A second recommendation for the tenure regimes of Bolivia and Paraguay would be to improve the municipal districts that must conform to the legal framework of the state and do not recognize the importance of Guarani institutions to their culture and wellbeing. These restrictions placed on the indigenous municipal districts reduce the power of the traditional kin leaders of the community and are a form of integrating the Guarani into the state system that dilute the cultural relevance of the community systems that have been in development for centuries [20][1]. We recommend that the national governments follow Free Prior Informed Consent guidelines and allow the Guarani Peoples to set the terms for which they are to create organizations to manage their land and dictate the way funds are shared communally[26].

Both Paraguay and Bolivia are countries that experience high levels of deforestation for land use conversion for agriculture and cattle ranching, and we suggest that along with the implementation of TG guidelines for monitoring, both countries should begin to legally adopt a form of mixed agroforestry similar to ones present within the Guarani communities [12][6][1]. We believe that adopting these new forestry practices could give recognition of Guarani knowledge and help to give this group more relative power and influence by emphasizing the importance of these communities to national wellbeing. On a small scale within Paraguay, organizations such as The Natural Conservancy and the FMB have began to implement management strategies incorporating Guarani developmental and management techniques within their protected areas to help conserve the flora and fauna of the lowland regions[1]. The Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) provided by Guarani Yerba collectors has began to be formally recognized by many NGOs in these areas and has created an open dialogue that has allowed for new colonists to begin to learn and implement the sustainable techniques of the Guarani People [1]. These small cases provide evidence of the value of incorporating Guarani communities into decision making processes. By implementing TEK it could help reduce the land conversion in Bolivia and Paraguay and provide the government with a new framework of sustainable natural resource use, while understanding the importance of these indigenous groups.

Conclusion

The Guarani People of Bolivia and Paraguay in South America are a resilient indigenous community and despite centuries of European colonization and contact have managed to retain their ethnic and cultural integrity[1]. However, through the 20th as multinational organizations began to gain tenure rights on large portions of Latin America the ancestral land of the Guarani was appropriated and the indigenous title rights to these lands were not recognized[6]. To help rectify this problem the nation states of Bolivia and Paraguay created superior legal frameworks by amending many state laws, constitutional reforms, and ratifying international agreements to recognize the additional rights the Guarani possess[5]. We believe that the steps taken by the governments are in the right direction to help return ancestral land, and we also recommend that with the implementation of TGs[18], acknowledging FPIC[26], and adopting the Guarani form of agro-forestry[1] that Bolivia and Paraguay can improve their tenure regimes and restore tenure rights back to the Guarani Peoples again.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 1.27 1.28 1.29 1.30 1.31 1.32 1.33 1.34 Reed, R. (2008). Forest Dwellers, forest protectors: indigenous models for international development. (D. Maybury-Lewis, T. . Macdonald, & C. Survival, Eds.) (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Brown, S. L. (2009). Guarani shamans of the forest by Bradford Keeney, Kern L. Nickerson and Rolando Natalizia: Ropes to God: Experiencing the bushman spiritual universe by Bradford Keeney, Paddy M. Hill and Bradford Keeney. Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions, 12(3), 128–132. https://doi.org/10.1525/nr.2009.12.3.128

- ↑ Luthrap, D. W. (1968). The “hunting” economics of the tropical forest zone of South America: an attempt at historical perspective. In R. B. Lee & I. DeVore (Eds.), Man the hunter (1st ed., pp. 24–30). New York, NY: Routledge.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Ballengee-Morris, C. (2019). Cultures for sale: perspectives on colonialism and self-determination and the relationship to authenticity and tourism. Studies in Art Education, 43(3), 232–245. https://doi.org/10.2307/1321087

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 5.19 5.20 5.21 Ortega, R. R. (2004). Models for recognizing indigenous land rights. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 6.17 6.18 6.19 6.20 6.21 6.22 6.23 6.24 6.25 6.26 6.27 6.28 6.29 6.30 Larson, A. M., Barry, D., & Dahal, G. R. (2010). Forest for people: community rights and forest tenure reform. (A. M. Larson, D. Barry, G. R. Dahal, & C. J. Pierce Colfer, Eds.). New York, NY: Earthscan.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR). (2009). Captive communities: situation of the Guarani Indigenous People and contemporary forms of slavery in the Bolivian Chaco (OEA/Ser.L/V/II., Doc 58). Washington, DC. Retrieved from https://www.oas.org/en/iachr/indigenous/docs/pdf/captivecommunities.pdf

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Bonomo, Mariano; Angrizani, Rodrigo; Apolinaire, Eduardo; Noelli, Francisco (2015). "A model for the Guaraní expansion in the La Plata Basin and littoral zone of southern Brazil". Quaternary International. 356: 54–73.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 Stocks, A. (2005). Too much for too few: problems of Indigenous land rights in Latin America. Annual Review of Anthropology, 34, 85–104. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.33.070203.143844

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Nagel, B.Y. (1999). ""Unleashing the Fury": The Cultural Discourse of Rural Violence and Land Rights in Paraguay". Comparative Studies in Society and History. Cambridge University Press. 41: 148–181.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 Morris, Christine; Mirin, Kaira; Rizzi, Christina (2000). "Decolonialization, Art Education, and One Guarani Nation of Brazil". Studies in Art Education. 41: 100–113. doi:10.1080/00393541.2000.11651669.

- ↑ 12.00 12.01 12.02 12.03 12.04 12.05 12.06 12.07 12.08 12.09 12.10 12.11 12.12 12.13 12.14 12.15 12.16 Tauli-Corpuz, V. (2015). Report of the special rapporteur on the rights of indigenous, Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, regarding the situtation of indigenous peoples in Paraguay (Vol. 1513734). Retrieved from http://unsr.vtaulicorpuz.org/site/index.php/documents/country-reports/84-report-paraguay

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Saguier, R.B. (1990). "Guarani Genesis; the intricate cosmogony of South America's 'forest theologians'". The UNESCO Courier: a window open on the world. (XLIII ed.). 5: 18–21.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 Quevedo, L. (2006). Forest certification in Bolivia. In B. Cashore, F. Gale, E. Meidinger, & D. Newsom (Eds.), Confronting Sustainability: Forest Certification in Developing and Transitioning Countries (pp. 303–336). New Haven, CT: Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies Press.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 15.7 Veit, P., & Sarsfield, R. (2017). Land Rights, Beef Commodity Chains, and Deforestation Dynamics in the Paraguayan Chaco. Washington, DC: USAID Tenure and Global Climate Change Program.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 Pasqualucci, Jo M. (2009). "International Indigenous Land Rights: A critique of the jurisprudence of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in light of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous PeoplesI" (PDF). Wis. Int'l L.J.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 De Pourcq, K., Thomas, E., & Van Damme, P. (2009). Indigenous community-based forestry in the Bolivian lowlands : some basic challenges for certification. International Forestry Review, 11(1), 12–26. https://doi.org/10.1505/ifor.11.1.12

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 18.6 18.7 Brent, Z. W., Alonso-Fradejas, A., Colque, G., & Sauer, S. (2018). The ‘ tenure guidelines ’ as a tool for democratising land and resource control in Latin America. Third World Quarterly, 39(7), 1367–1385. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2017.1399058

- ↑ Ackermann, Fran; Eden, Colin (2011). "Strategic Management of Stakeholders: Theory and Practice". Long Range Planning. 44 (3): 179–196.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 Jamal, T., Kreuter, U., & Yanoisky, A. (2007). Bridging organisations for sustainable development and conservation : a Paraguayan case. International Journal of Tourism Policy, 1(2), 93–110. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTP.2007.015522

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 "Forest Stewardship Council: WHO WE ARE". FSC Worldwide.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Larson, Anne; Pacheco, Pablo; Toni, Fabiano; Vallejo, Mario (2007). "The Effects of Forestry Decentralization on Access to Livelihood Assets". The Journal of Environment & Development. 16: 251–268.

- ↑ "What We Do". Survival International. Retrieved 04/03/2019. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Elgert, Laureen (2015). "'More soy on fewer farms' in Paraguay: challenging neoliberal agriculture's claims to sustainability". The Journal of Peasant Studies. 43: 537–561.

- ↑ A.M., Larson; Barry, D.; Dahal, G.R. (2010). "New rights for forest-based communities? Understanding processes of forest tenure reform". International Forestry Review. 12: 76–96.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2016). Free prior and informed consent manual. Retrieved April 4, 2019, from http://www.fao.org/3/a-i6190e.pdf

| This conservation resource was created by Georgina and Kelsey. It has been viewed over {{#googleanalyticsmetrics: metric=pageviews|page=Course:CONS370/2019/ Title and land rights of the Guarani peoples of Paraguay and Bolivia, South America.|startDate=2006-01-01|endDate=2020-08-21}} times.It is shared under a CC-BY 4.0 International License. |