Course:CONS370/Projects/Indigenous community engagement and associated turtle marine conservation efforts in Ostional, Costa Rica

| Country: Costa Rica | |

| Province/Prefecture: Ostional | |

This conservation resource was created by Course:CONS370. | |

Sea turtles are one of the earth's oldest, most treasured species, but due to human-caused extinction threats six out of the seven species/populations are now in danger. Ostional, Costa Rica known as being one of the largest turtle nesting sites in the world, sees tens of thousands of sea turtles come to nest ashore its beaches annually. Local communities have relied heavily on turtle eggs for subsistence and traditional livelihood practices and, as a result, egg harvesting has significantly impacted the turtle populations. In 1983, the Ostional National Wildlife Refuge (ONWR) was established on traditional Matambú territory, the unceded and ancestral home of the Chorotega people. The refuge is designated as a Combined Property Refuge, jointly owned by the state and communities residing within its jurisdiction where management and community involvement targets the sustainable harvesting of sea turtle eggs and simultaneous species protection. Development of the Council of the National Interagency Wildlife Refuge Ostional (CIMACO) has aimed to increase community participation, input, and cooperative management regimes and includes a variety of stakeholders from government, academic institutions, and local communities. Although the management approaches and methods used in Ostional sea turtle conservation have been primarily effective, it still has its barriers to overcome. Moving forward, sea turtles' intrinsic importance to the environment and local Indigenous Peoples will become increasingly important in perpetuating this community-based conservation project, whether by consumption or other activities.

Description

This case study examines the local community in Ostional, Costa Rica and their relationship with marine turtle egg conservation on the site. The community of Ostional is located in the village of Ostional near one of the world’s nine known mass sea turtle nesting sites[1]. An 800m stretch of beach along the Pacific coast on the Nicoya peninsula is where Olive ridley turtle mass nesting occurs. Although many marine turtle species nest in Ostional, only Olive ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea) sea turtles congregate for mass nesting[1]. These mass nesting periods are referred to as arribadas, arribada being the Spanish word for ‘arrival’. During monthly arribadas, between 20,000 and 160,000 turtles nest together over a 3-10 day period[1].

The community of Ostional was founded in 1902 and depended primarily on animal husbandry and agriculture[2]. The community’s livestock would feed on sea turtle eggs along the beach and some marine turtle eggs would be harvested for human consumption and trade[2]. Sea turtle egg harvest became illegal in the 1970s, resulting in a loss of legal consumptive-use of marine turtle eggs for local Ostional populations[2].

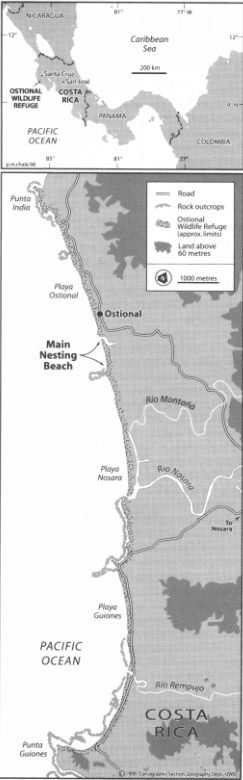

In 1983, the Ostional National Wildlife Refuge (ONWR) was established to protect turtles nesting in the area[2]. The ONWR spans 14 kilometers along the Pacific coast of Costa Rica on the Nicoya peninsula and includes the 800m stretch where the Olive ridleys congregate for monthly mass nesting (See Ostional Wildlife Refuge in Figure 1). The goals of the ONWR are to manage sustainable use of the beach and its resources while gaining community support via participation, planning, research, protection, control, ecotourism, and environmental education[3]. The community of Ostional appealed to Dr. Douglas Robinson at the University of Costa Rica to begin a legal egg harvesting program at Ostional[3]. This egg harvesting program would provide several community benefits and further conservation efforts at the ONWR. The first legal marine turtle egg harvest took place in 1987[1], and the egg harvesting program continues its operations today.

Costa Rica has 24 indigenous territories inhabited by different indigenous and non-indigenous peoples. The Ostional National Wildlife Refuge (ONWR) is located on traditional Matambú territory, home to the Chorotega people[4]. Unfortunately, Indigenous territorial rights are constantly violated in Costa Rica and over half the area of some territories are occupied by non-indigenous settlers[5]. Rights to land and self determination are challenging aspirations for the country’s indigenous population[5]. Those who hold political and economic power in Costa Rica have been actively resisting indigenous rights to land and the self-determination of indigenous peoples, resulting in major inequalities in the country[5].

Project Aim

Sea turtles have existed on Earth for more than 100 million years, but their survival is now in jeopardy. Human-caused extinction threatens six of the seven sea turtle populations, due to bycatch in fisheries, coastal growth, plastic contamination, and the consumption of sea turtles and their eggs[6]. The ultimate goal of community and Indigenous based sea turtle conservation efforts is to meet a previously unmet global need for sea turtle protection through community led sea turtle conservation programs[7]. The project aims to partner, involve, and facilitate an exchange of information between local people and organizations to produce critical conservation efforts for sea turtle survival. In bringing together local values and knowledge with science and conservation, the project can create a sustainable future for sea turtles in Ostional and all around the world for that matter[3].

Tens of thousands of turtles come ashore to nest on Ostional’s tiny stretch of beach, and out of the millions of eggs laid, fewer than one in a thousand result in a turtle hatchling making it to the ocean, even with no human intervention[8]. Some are dug up by natural predators such as coyotes and vultures, but still more are killed when subsequent waves of turtles arrive on following nights. Surprisingly, human inflicted death, predation, and even mass collection has a negligible effect on overall success rates of turtle hatchlings. Just about a quarter of the nests that survive the entire incubation period establish and hatch baby turtles[1]. Knowing these facts, scientists can carefully monitor collecting part of the excess turtle eggs. This project is able to tie together traditional Indigenous knowledge and practices with modern day scientific knowledge in order to come to common ground; the sustainable use of sea turtle eggs which are inventoried and certified for legal sale providing income for the locals and for future conservation efforts[8].

Locals, including Indigenous groups, are passionate about protecting the turtle’s habitat, nests, and hatchlings as they migrate to the Pacific. The project, in raising awareness has virtually eliminated the local egg black market in this area, reduced questionable fishing practices by foreign fleets (due to conservation pressure financed with profits), and improved the quality of the beach by removing waste, runoff, and ATVs, among other things[9]. The project in Ostional has and will continue to strive for fluidity between local Indigenous traditions and conservation goals. Turtle eggs available for consumption from the project in Ostional are collected legally and under the guidance of wildlife biologists with the income from the sales going towards future turtle conservation projects[9]. Ultimately, the project has the ability to deepen community connectedness and place value in traditional Indigenous values, all while emphasizing environmental conservation.

Project Challenges

Since the 1970s, sea turtles have been protected by national and international legislation, but illegal and unsustainable sea turtle harvesting continues, especially in Indigenous communities as a source of food[2]. In coastal communities, sea turtles are seen as a valuable but fragile source of food, which is a source of disagreement and conflict. However, there are now few areas on the planet that allow the use of any sea turtle product, and where it is legal, use and trade are limited to rural Indigenous communities near nesting beaches[2]. As a result, communities are discouraged from eating sea turtles by alternative livelihood strategies which raises the question as to whether or not it is right to interfere with traditional values[2].

Monthly mass nesting of olive ridley sea turtles occurs at Ostional on Costa Rica's Pacific coast. Often, the local population takes advantage of these mass nesting's by harvesting eggs for consumption and sale. The egg harvesting project at Ostional is the only outlet for a legal nationwide supply chain of sea turtle eggs, in contrast to restricted non-commercial use of sea turtle eggs[2]. Millions of turtle eggs are legally collected and sold/consumed by the residents of the community of Ostional every nesting season under the supervision of rangers and biologists at the refuge. Although many outsiders believe this to be unjust or a “turtle massacre”, there are many good aspects to come from legally harvesting sea turtle eggs and it is believed that the good far outweigh the bad[6].

In general, the tension between conservation and growth goals leads to inevitable compromises in the efficacy of integrated interventions[2]. As a result of a high reliance on external funding, low local involvement, non-devolved management rights, and elite capture of project revenues and benefits, current initiatives have had minimal success in achieving their multiple goals of wildlife protection, stakeholder engagement, revenue generation, and growth[2]. Community-based conservation, on the other hand, specifically incorporates development goals, seeking to maximize resource exploitation for long-term sustainability and knowledge to achieve conservation goals, and has been shown to build capacity to adapt to global change through trust and collaboration networks[2].

There is other potential downside to the locally led conservation efforts in Ostional. It has been proposed that the availability of legal turtle eggs on the market provides protection for the sale of illegal turtle eggs in bars and restaurants[10]. This may be valid to some extent, but it's a good idea to put the income gained from this trade into poaching elsewhere and promoting turtle conservation locally and globally. It would be a different story if people were collecting turtle shells, but that isn't the case. It's a fantastic example of how humans and animals can coexist and even flourish.

Despite the fact that consumption of wildlife is frowned upon in industrial communities, projects like the egg harvesting project show how regulated and legalized use of wildlife resources can incentivize and meet conservation goals. Globally, the socioeconomic advantages of resource utilization have resulted in favorable conservation outcomes. Sea turtles and the arribada phenomenon were considered a special feature of respondents' community identity and heritage in this research. Their refusal to consider a fortress conservation scenario is in line with global proof of inclusive conservation's benefits. As the egg harvesting project's economic and dietary dependency fades, the turtles' intrinsic importance to the environment will become increasingly important in perpetuating this community-based conservation project, whether by consumption or other activities[2].

Tenure arrangements

The Colonial period in Costa Rica began in the early 1500’s when first contact was made between the Spanish and Indigenous Peoples from across the region. Since then, legislation within the Costa Rican government has failed to favour Indigenous autonomy over their traditional and unceded lands[5]. No treaties currently exist within the country of Costa Rica between the government and any of the eight Indigenous groups that exist within the region[5]. The United nations Universal Periodic Review of Costa Rica in 2018 on Cultural Survival explained that “Colonization of Indigenous territories by non-indigenous individuals is a troublesome phenomenon that has not yet been solved in Costa Rica…[the] Costa Rican government, which fails to provide clear judicial, political, or administrative processes for evicting these non-indigenous people from these colonized indigenous territories”[3].

The Ostional National Wildlife Refuge is located in the province of Guanacaste in Costa Rica on traditional Matambú territory, the ancestral home of the Chorotega people[4]. The Ostional National Wildlife Refuge is designated as a National Protected Area (NPA) within the Tempisque Conservation Area spanning distances across both land and sea[3]. For many years, the protected area was solely owned by the Costa Rican government. More recently, the Ostional National Wildlife Refuge has been designated as a Combined Property Refuge and owned by the state and community. Egg harvesting is monitored and authorized by the Ministry of Environment and Energy (MINAE) through the National System of Conservation Areas (SINAC)[2].

Three local communities of Ostional, Peladas and Guinoes Sur currently reside within the borders of the Protected Area and are closely tied to the refuge. ONWR corresponds to the marine-terrestrial zone (MTZ) of Ostional, Nosara, Peladas, and Guinoes beaches. As of 2016, following the proclamation of Law 18939 “Ostional Wildlife Refuge Law'', tenure of the Ostional National Wildlife Refuge now allows private properties to be duly registered within the refuge, transferring away from being government owned[11]. Until recently, individuals residing within jurisdiction of the wildlife refuge did not legally own their lands and homes[11]. The Ostional Wildlife Refuge Law aims to provide fair and sustainable use of natural resources through the participation of local communities that reside within its jurisdiction[12]. However, there is still much controversy regarding its potential loopholes into private development in the area. Debates and controversy regarding coastal development xxxx[11]. There has been a long-term land dispute between locals and the Environment Ministry regarding land rights and ownership, as many families have resided within the area before establishment of the wildlife refuge back in 1983[11]. As the Ostional Wildlife Refuge is located within the Maritime Zone, the first 50 meters from a high tide mark belongs to the municipality[12]. No prior consent or consultation regarding the establishment of the Ostional National Wildlife Refuge was carried out, causing many locals to suffer economically and emotionally as they were no longer allowed to gather turtle eggs from the Olive Ridley Sea Turtle[12]. In many cases, individuals living in the area did not know that the refuge had been declared[12]. Since then, farther xxx. Although many land disputes have been resolved in recent years, there is still more work to be done[13]. However, through community based management approaches within the wildlife refuge, more trusting and engaged relationships have been created between government and local communities[14].

Institutional Arrangements

Since the harvest of marine turtle eggs at Ostional has been legalized, there are several rules in place to ensure sustainable egg harvest at the ONWR. The first of these rules maintains the Olive ridley sea turtle eggs may only be harvested during the monthly mass nesting periods called arribadas[3]. Each month a document is produced indicating the date and time the the arribada began, as well as the arribada’s location[3]. This document initiates the legal collection and marketing of marine turtle eggs in Ostional. The harvesting period for Olive ridley turtle eggs begins at the time of the arribada declaration document, and continues for the daylight hours until noon on the third day of the arribada. Exploitable nests must be located through scoring of the sand with one's hands and/or feet during this time period. Another rule requires that the Ostional Development Association (ADIO) appoints a permanent monitoring group to protect turtle nests outlined in an approved management plan (ADIO must also conduct restorative activities which improve the site’s habitat). Along with this, egg collection for experimental purposes is prohibited at certain locations. Finally, communication strategies for marine turtle management and conservation is the responsibility of those institutions involved in the turtle conservation project itself[3].

The packaging and transportation of Olive ridley sea turtle eggs is another aspect of the egg harvesting project at Ostional which is heavily regulated. ADIO sealed and stamped boxes are to be filled with ten synthetic fiber bags, each containing ten eggs grouped by grade[3]. The eggs may only be transported from beach to market in vehicles regulated by the Costa Rican Institute of Aquaculture and Fisheries (INCOPESCA) and the National Service of Agri-Food Health and Quality (SENASA)[3]. Since egg harvesting is monitored and authorized by INCOPESCA and the National System of Conservation Areas (SINAC), both institutions must be notified about all updates concerning sales, dealers, egg transportation information, and permits[2][3]. These measures ensure maximum benefits for both marine turtle conservation and for the local community.

Stakeholders

Rights Holders, Stakeholders, and User Groups: Their Impacts, Main Objectives and Relative Power

The Ostional National Wildlife Refuge (ONWR) was established in 1983 by the Ministry of Environment and Energy (MINAE) with the primary goal of protecting sea turtle nesting at Playa Ostional, Costa Rica[3]. Marine and National Protected Areas represent the front lines of tension between conservation and the development within the increased growing trends towards sand, sun, and sea tourism development[3]. Since 2008, there has been a development in the management of ONWR through an inter-institutional advisory council called the Council of the National Interagency Wildlife Refuge Ostional (CIMACO)[14].

The council board is composed of members from within the local communities, The University of Costa Rica (UCR) —specifically researchers from the School of Biology, representatives from local associations, the National Fishing Institute, and members of the local municipal governments[3]. The council aims to encourage participation of communities in the conservation, management, and sustainable use of natural resources within the wildlife refuge[14]. Through CIMACO, the reserve is aiming to lead towards a more eco-touristic approach for both conservation and communities by providing legal extraction of turtle eggs and —acting as a provisioning service for local community members[14]. However, due to power indifferences that exist between government agencies and community members, there leaves room for unequal power sharing in the realms of, decision making, policy, and management operations[15]. In addition to the stakeholders and user groups who are involved in CIMACO, additional stakeholders include: Ostional Development Association (ADIO), Costa Rican Institute of Aquaculture and Fisheries (INCOPESCA), the National Conservation System, and Tempisque Conservation Area (ACT), and the Ostional Guides Association (AGLO)[3].

Beach guides have helped to guide safe and respectful ecotourism engagement with visitors to protect Ostional sea turtle habitat while educating visitors. Currently, two groups of tour guides exist within the Ostional National Wildlife Refuge[16]. The Ostional Development Association (ADIO) has fifteen guides, as does the Ostional Local Guide Association[16]. Visitors to the beach are only permitted to enter if accompanied by licensed guides from one of the two guide groups. Two groups of tour guides within the ONWR: one with ADIO and a private local association, each with fifteen guides[16].

Three local communities currently reside within the borders of the National Protected Area (NPA): Ostional, Peladas, and Guinoes Sur[17]. Many conflicts have arisen over the years between stakeholders[17]. Local community members lacked trust in the government to adopt a cooperative plan to manage the area in a way that would have social, economic, and ecological benefits to the region[3]. Residents living within jurisdiction had poor living conditions and did not legally own their land and homes. Prior to 2004, there was no legal framework, management plan, public border, or budget management to help guide effective and just management to the wildlife refuge[16]. In 2003, the Minister of Environment and Energy and other stakeholders including the fisheries agency (INCOPESCA), local communities, the University of Costa Rica (UCR), local guides, and fishermen commenced the actions of the Participatory Environmental Management Plan (PEM)[14]. The main goal of the management plan was to include diverse knowledge sourcing from traditional, scientific, technical, and administrative knowledge[3]. In order to address concerns regarding the livelihoods and wellbeing of community members, in 2012, the refuge permitted the sale of turtle eggs and encouraged eco-tourism[3]. Proper management of the protected area would not have been possible without the participation from civil society in the decision making process[17]. The best approaches to conserve wildlife come from giving communities more control over the management and environment in which they live everyday[3]. Across most of the tropics, conservation reserves and management function through a top-down process[16]. Major actors include the government, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) —and are often seen as foreign intervention. Due to the lack of inclusion towards local communities, members are frequently hesitant to support restrictions and guidelines “on the means of their livelihoods in the name of biodiversity protection”[3]. “Local communities often live along beaches where sea turtles come ashore to lay their eggs. Protection of those beaches, therefore, either involves removing the people from a new protected area or involving the people in the protection itself.”[3]. However, through the establishment of CIMACO and PEM, many local communities have grown to support ONWR through this more democratic approach to conservation management[3].

Project Governance

As with any project that involves political, cultural, and social influences of power, the case of the Ostional turtle conservation project involves significant power implications. The local Indigenous communities (the Ostional, Peladas, and Guinoes Sur), local and national government, along with international and local conservation groups, are all involved parties in the influence of power on the region.

On an international scale, increased and widespread impacts in areas outside national control (ABNJ) have prompted calls for better management of high seas fisheries, the use of marine genetic resources, deep-sea mining, and species conservation[18]. The sustainability of the global ocean commons will have an effect on all humans; however, this diversity is rarely expressed in UN processes and negotiations. Government officials take part in discussions according to existing protocols, with UN agencies, non-governmental organizations, and, on occasion, academia providing active feedback. Indigenous peoples and local populations, on the other hand, have been disproportionately underrepresented[18].

In the case of Ostional and sea turtle conservation, the Refuge is a Combined Property Refuge, jointly owned by the state and the community. Egg harvest in the area is authorized by the Ministry of Environment and Energy through the National System of Conservation Areas, and the egg trade by the Costa Rican Institute for Fisheries and Aquaculture[2]. To trade eggs across the country, the distribution system includes licensed distributors and resellers, government-issued permits and licenses, and specialized packaging[2].

Recommendations

An analysis of published literature, informative articles, and local interviews of past and present studies surrounding sea turtle conservation efforts in Ostional, Costa Rica has brought about the following recommendations:

- Indigenous peoples and local populations must be included in future Ostional conservation decisions as a primary stakeholder.

- International policy decisions that directly affect Indigenous Peoples (such as species conservation decisions) need to consult and take into better consideration the values of Indigenous Peoples, specifically, traditional, cultural, and spiritual values.

- Non-Governmental-Organizations (NGO’s) have and will continue to play a major role in shaping the Ostional turtle conservation efforts. It is recommended that further government funding (both national and international) go towards helping these organizations and their conservation goals.

- Make room for more collaborative opportunities between government/official stakeholders with local and Indigenous. Must work towards breaking down barriers of power (allow for more power sharing) and allow for ongoing and collaborative adaptive strategies for conservation management in the refuge

- Adopt a co-management framework that emphasizes power sharing, governance sharing, co-production of knowledge

- Continue to/encourage more transparency in decision making with communities through consultation and FPIC

- Farther resolution of land disputes and claims within the wildlife refuge, as well as recognition of Indigenous territories, land rights, and farther recognition of UNDRIP

- Create and/or strengthen existing policy or legislation which recognizes Indigenous rights and supports and empowers Indigenous self-determination

- Provide education, training, and employment opportunities for Indigenous community members

- Fund, establish, and/or support alternatives and incentives for marine habitat conservation

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Cambell, L (1998). "Conservation and the consumptive use of marine turtle eggs at Ostional, Costa Rica". Environmental Conservation. 25(4): 305–319.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 Sardeshpande, M; MacMillan, D (2019). "Sea turtles support sustainable livelihoods at Ostional, Costa Rica". Fauna & Flora International. 53(1): 81–91.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 3.21 Orrego, C; Rodriguez, N (2018). "The positive relationship between the Ostional community and the conservation of olive ridley sea turtles at Ostional National Wildlife Refuge in Costa Rica". Marine Protected Areas: Interactions with Fishery Livelihoods and Food Security. 69.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Nativeland (2020). "Nativeland".

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 "Indigenous Peoples in Costa Rica". 2020.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 CLI Nature Conservation (2020). "ANAI".

- ↑ Arauz, R; Naranjo, I (2000). "Conservation and research of sea turtles, using coastal community organizations as the cornerstone of support-Punta Banco and the indigenous Guaymi community of Conte Burica, Costa Rica". Eighteen International Sea Turtle Symposium: 238–240.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Costa Rica guide (2021). "Sustainable Harvest of Sea Turtle Eggs".

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Klopfer, K (2014). "Sustainable Community-run Development: Experiences from the ADIO Project in Ostional, Costa Rica". School of Geography, Environment and Earth Sciences Victoria University of Wellington New Zealand.

- ↑ Pritchard, P (1980). "The Conservation of Sea Turtles: Practices and Problems" (PDF). American Zoologist. 20(3): 609–617.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Morales, H; Garcia, H (2018). "New Ostional law allows private properties Within Refuge".

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Guillermo, L (2018). "SOLIS: The Ostional law does not say that all restrictions are lifted so that they can start building hotels".

- ↑ NAOO (2014). "Olive ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea) 5-year review: Summary and evaluation".

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 Campbell, L; Haalboom, B; Trow, J (2007). "Sustainability of community-based conservation: Sea turtle egg harvesting in Ostional (Costa Rica) ten years later". Environmental Conservation. 34(2): 122–131.

- ↑ Carlsson, L; Berkes, F (2005). "Co-Management: Concepts and Methodological Implications". Journal of Environmental Management. 75(1): 65–76.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 "Olive Ridley Turtle". 2021.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Chu, V (2015). "What's It Like Saving Endangered Baby Sea Turtles in Costa Rica?".

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Vierros; et al. (2020). "Considering Indigenous peoples and local communities in governance of the global ocean commons". Marine Policy. 119. Explicit use of et al. in:

|first=(help)