Course:CONS200/The story of Canada's digital dumping ground

| This conservation resource was created by Alyssa Hunt, Makenna Bailey, Mark Buglioni, and Megan Berry. |

Introduction

Electronic Waste

Every year we contribute exuberant amounts of waste to our landfills. One of the largest global contributors to that waste comes from our electronics, also known as e-waste. In 2016 alone approximately 44.7 million metric tonnes of e-waste were created[1]. By 2020, it is predicted that that amount will increase by 17% and we will create approximately 52.2 million metric tonnes of e-waste annually throughout the world[1]. Canada is a large contributor to this e-waste problem. A report released by Statistics Canada stated that, in 2012 we contributed 14.3 million tonnes of waste to the global e-waste problem [2].

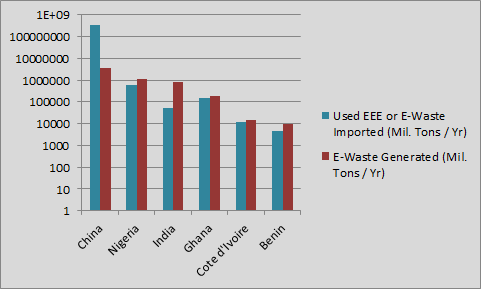

Besides the accumulation of waste, a larger issue resides within the disposal of electronics. How Canada, and other developed nations, are dealing with these waste products is causing major environmental problems.The disposal of e-waste is a delicate matter. If improperly disposed of, e-waste can contribute to the release of environmental toxins that are linked to the development of cancer and neurological disorders [3]. These dangerous by-products are most often noticed in developing countries, as developed countries like Canada and the United States are known for shipping their e-waste to places such as West Africa, India and China [4].

Measures have been taken to reduce the transboundary, unsafe disposal of electronic waste from Canada and other countries. In Canada, Environment Canada’s Waste Reduction and Management Division (WRMD) works with and represents the country on affairs regarding electronic waste [5]. Canada has also signed the 1992 Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal, a United Nations Treaty to protect the environment and humans alike from transboundary dangerous waste [6]. Even with measures in place, electronic waste continues to be smuggled out of Canada to developing countries [7].

Nature of The Issue

E-waste has been an ongoing issue for many years now. Due to the fast growing nature of new technology, we are seeing more and more e-waste production. The environmental implications of throwing away an old cellphone, television or laptop are often not common knowledge. It is estimated that in 2016, only 20% of global e-waste was collected and recycled properly[1]. When e-waste is broken down and recycled in a safe and controlled environment, it can have minimal negative impacts. Environment Canada is responsible for ensuring this is done so in as much of the country as possible [8]. As of 2014, 9 provinces in Canada were required to meet Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) guidelines when dealing with their recycled e-waste [8]. A wide variety of electronics, appliances and accessories can become e-waste. Common things such as televisions, cellular phones, refrigerators, modems and batteries are all at risk of contributing to e-waste [9]. When we properly recycle our electronics, they are sent to refurbishing and recycling centres across the country [8]. These centres follow specific protocols and considerations to disassemble the devices and ensure the different materials are properly recycled and disposed of [8]. However, when devices are improperly disposed of, they enter landfills. This is where they pose the greatest environmental and health risks to society. Although there are countless landfills across the country, Canada has been recognized as one of the developed nations that contributes to international dumping of waste [10]. In 2013, Canada sent 50 shipping containers to a port in Manila, in the Philippines [10]. These containers were mostly plastic waste and represent just a fraction of the total waste that is sent across international waters every year from Canada [10].

A Global Issue

This e-waste problem is not only a Canadian issue, but a global one. Developed and high-income countries have the ability and resources to properly manage and deal with their e-waste [11]. However, developing and low-income countries don’t have that luxury. [11]. The lack of resources to properly manage this issue comes at a cost [11]. Countries such as India and the Philippines are at greater risk for the hazardous side effects that come with improper e-waste disposal[11]. In 2011, the world became more globally aware of the scale of the e-waste problem and organizations began to take action[12]. The International E-Waste Management Network (IEMN) was created through the collaboration of the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Environmental Protection Administration Taiwan (EPAT) [12]. The organization was created to give global officials the ability to exchange techniques and practices with each other for appropriate e-waste management [12]. The severe negative impacts of e-waste are also globally felt [13]. In southeastern China, at one of the world’s largest e-waste recycling centres, health problems such as bone issues and respiratory ailments have occurred[13]. However they haven’t just been noticed close to the e-waste centre, these toxins are being released in the air and are travelling with the wind to other nearby regions, causing very similar health problems there[13]. The severity of the e-waste problem is immense and it is still growing.

If we fail to take action towards this global issue it will affect some more than others. Although the effects would likely be felt internationally, due to recycling program status, medical care availability and quality of life in an area, the effects will be worse for some compared to others. In nations such as Canada, health, safety and the environment are at the forefront of all considerations made in the e-waste industry [8]. This ensures that all decisions and initiatives taken are done so with the nation and its individuals best interests in mind. However, places such as India don’t have the same guidelines or strict criteria. The first e-waste law wasn’t implemented in India until May 2013 [14]. This law was designed to reduce the amount of waste that was incoming to the country, by creating collection centres where electronics can be taken back by the manufacturers to ensure they stay out of landfills[14]. In the event that action isn’t taken, developing nations will get the worst of the negative effects. They are often the countries with the more primitive laws and regulations and unfortunately are subject to the harm caused by developed nations.

Evidence of the Problem

Electronic Waste Management in Canada

Electronic waste has been a focus of the Canadian government for almost 19 years [15]. It is recognized as a major source of pollution, and can often have toxic components [16]. As Canadians continue to buy more electronic devices, e-Waste accumulates. In 2010, around 224,000 tonnes of e-waste was created in Canada [15]. Environment Canada is the controlling power managing e-waste although the government co-manages electronic waste with many organizations [15]. E-waste management has been divided into different levels of administration. The Federal, Provincial, and Municipal governments, as shown below, all handle different aspects of e-waste management [15].

| Examples of Duties | |

| The Federal Government | Managing Canadian-International E-Waste Affairs [15] |

| The Provincial Governement | Managing the transfer of E-Waste through provinces [15] |

| The Municipal Government | Managing Local Recycling Services [15] |

Canadian organizations such as EPRA or Electronic Products Recycling Association handle the physical management of electronic waste. EPRA claims to keep “100,000 metric tons of old electronics out of landfills every year.” [17]. The organization works by collecting electronic waste at approved sites, then recycling products while recollecting raw materials [17]. Toxic materials in the electronic waste are also handled through EPRA recycling methods [17]. Other not-for-profit organizations influencing Canada’s E-Waste Management include the EPSC, or Electronics Product Stewardship Canada. This organization works to apply “sustainable solutions” [18]. in Canadian E-Waste management. Both organizations, and others similar to them, work alongside the Canadian government, co-managing the issue of electronic waste.

Challenges and On-Going Issues

Even with many levels of Canadian government and organizations working together, electronic waste management is an ongoing issue. The exportation of dangerous E-Waste to developing countries continues, often in illegal forms. investigation of multiple Metro Vancouver companies, PC Max and E-Tech, exporting illegal E-Waste in 2014 highlight the ongoing struggles to contain the problem [19]. International laws continue to be broken, as dangerous E-Waste handling can be a profitable criminal activity [19] Another example of the exportation of illegal waste is the fines given to Surrey, British Columbia based company, Electronics Recycling Canada for violating international law in 2015 [20]. The company made multiple shipments of “cathode-ray-tube monitors and batteries” to China in 2011[7]. Instances such as these prove illegal E-Waste exportation still exists, hidden under Canadian management. The management of Electronic Waste has improved in Canada since the Basel Convention became effective in 1992[15]. Although, as displayed by the evidence of the continued illegal exportation of electronic waste, not enough is being done to eliminate the problem.

Electronic Waste Health Risks

Overview

Electronic Waste can contain toxic pollutants and materials such as lead and mercury [21]. These materials can be safely recovered, but may not always be handled properly. With a countless number of disposed of electronics, sometimes carrying over “five pounds of lead” these toxic materials are a major hazard [21]. Lead can be shown to cause numerous problems in humans such as anemia, nausea, insomnia, among others [21]. Not only can these materials harm humans and other organisms they can degrade the environment, hurting organisms indirectly [21]. When electronic waste is transported out of developed countries, this transfers the problem to others handling the waste. Often this harmful waste handling lands upon people “on the margins of society” [21].

Studies and Findings

Studies have shown humans around electronic waste recycling sites can expose humans to high levels of dioxin-related compounds (DRC) [22]. Dioxins are persistent environmental pollutants or (PEPs) [23]. In one study, the pollutants inhaled at an E-Waste recycling centre in Vietnam may have resulted in high levels of dioxin-related compounds in breast milk samples from women [22]. The DRC in the milk can then be fed to infants at “an order of a magnitude higher than a WHO tolerable dose” [22]. Dioxins accumulate in human bodies for an estimated “7 to 11 years” [23]. They are extremely toxic and can cause cancer, developmental and immune system problems alongside other damaging problems[23]. Infants are among the most sensitive groups of dioxin exposure [23].

Another study in Nigeria tested toxic metal levels by “standard electrothermal atomic absorption spectrometry” in humans/workers exposed to E-Waste [24]. Humans working with and around electronic waste showed elevated blood levels of metals such as lead, mercury, and arsenic[24]. These toxic metals can cause cancer and other extremely harmful effects[24].

Options for Remedial Action

While e-waste is a growing issue in developed and developing countries, there are many remedial actions that can be taken to comply with the different needs of each nation. Multiple technology advances are occurring every year, introducing newer versions of telephones, computers, televisions, cameras, video games, keyboards, etc., that people feel inclined to purchase, ultimately leading to more e-waste. Even though there are various options for disposing of e-waste, a much simpler solution is for the inventors behind such advances, is to stop creating newer, yet very similar, versions of what is already made. Computer keyboards, for example, in 1992 had a lifespan of about 4.5 years, whereas now, a lifespan consists of about 2 years if lucky [25]. The idea that we need to update our electronic devices every couple of years is a societal norm enforced by most industries, specifically telephone companies, who give out new phones (at a discounted price) at the end of three-year phone contracts. Reducing the amount of e-waste in Canada can merely be done by not purchasing electronics until absolutely necessary (i.e. broken).

Extended producer responsibility (EPR) is a program that follows the same guidelines as the polluter-pays principle, ensuring that a nation is responsible for the pollutant effects they put on the environment. EPR makes manufacturers responsible for taking back their products once there is no more use for them [25]. This EPR program is run by nations with more knowledge on the e-waste issue such as the European Union, Switzerland, Japan, United States, and Canada [25]. Multiple municipalities in Canada voted that their manufacturers should be responsible for e-waste production and so, by the end of 2010, the government of six Canadian provinces, Alberta, British Columbia, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Prince Edward Island and Saskatchewan, agreed to take back only seven electronic items, including computers, monitors, printers, “peripherals” (i.e. keyboard, mouse), televisions, DVD players, and CD players [25]. EPR provides a source of disposal for e-waste, instead of it going to our landfills where toxic materials can threaten our environment.

In hopes of limiting the amountof e-waste that ends up in landfills, Canada has introduced another program called the Electronic Product Stewardship (EPS). This program looks to further extend producers responsibilities (EPR) at both federal and provincial levels by pushing electronic manufacturers to start making more ecofriendly devices without the use of any toxic materials [26]. Nine of the provinces in Canada including British Columbia, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Ontario, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador and Alberta are all under the effects of this EPS program [26]. Since 2004, this organization has prevented 380,000 tones of e-waste from entering our landfills through reusing and recycling methods [26].

Preventing electronic products from entering landfills and incinerators by proper disposal, it saves the environment from the toxic materials that they release and from taking up space in landfills. Proper disposal of electronics starts by sifting through e-waste and using the viable leftover materials to be “recover[ed] and re-introduc[ed] into the manufacturing process” [27]. This process ties together with the phrase of reduce, reuse, recycle, however, not all recovered materials can be used in the production of new electronics [27].

Canada has several organizations at both federal and national levels to deal with the collection and recycling processes of electronic waste [28]. Listed below are all nine organizations located in Canada:

- Returnit

- ElectroRecycle

- Switch the ‘Stat

- LightRecycle

- AlarmRecycle

- OPEIC

- Call2Recycle

- Recycle My Cell

- Rethink It

These programs are there for collecting of e-waste which then gets transferred out for further recycling processes. These e-waste programs are available throughout Canada and are available to all provinces. British Columbia uses all but one program (Rethink It) in efforts to reduce as much e-waste as possible [28]. There are drop-off locations all around the country making it easily accessible for citizens, while also preventing cross-contamination by each person sorting their own e-waste [28].

Conclusion

Dear Environment Canada,

The purpose of discussing the topic of Canadas digital dumping ground is to bring awareness to the misuse of e-waste across the nation (S). With Canada having greater access to heal care resources, we have the ability to help developing countries with their growing concerns of indirect harmful effects of e-waste, rather than continually dumping waste in their communities. [4] While actions have already been put in place to reduce the transboundary, unsafe disposal of electronic waste (Waste Reduction and Management Division, and the 1992 United Nations Treaty, Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movement of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal) Canadas e-waste continues to be an ongoing environmental concern. With approximately 44.7 million metric tones of e-waste being creating in 2016 alone [1], this is becoming a growing environmental concern across the nation with a projected increase of 17% by 2020 [1].In 2016 it was recorded that only 20% of global e-waste was recycled correctly [1] showcasing the need to find alternative methods and practices of disposal [15]. Environment Canada's role has entailed managing these e-waste products, with the government co-managing alongside other organizations [13], and through the proposed actions can continue to uphold a positive role in Canada's digital dumping ground.

Rationalization of Preferred Option

With your sector of the government controlling toxic substances, and fostering environmentally sound management [29] you have the ability to foster the posed remedial actions, benefiting the nation, and the world as a whole. The preferred option for the remedial actions posed above is to impose the Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), following the same guidelines as the polluter-pays principle [25]. Through this action, manufacturers will be responsible for taking back their products once no longer needed or used, reducing the amount of excess e-waste [26]. The government, at all levels, can promote implementation through rule-making. As seen previously in Thailand, a Policy Engagement and Communication Program (PEC) was held with the purpose of engaging and sharing within a policy space to generate future positive influences to change current trends [22]. In combining both of these strategies, the public sector can encourage both strategies indirectly through organizing an agenda to implement strategies and commence a dialogue. The role of environment Canada should be to provide welfare for both citizens, community, and environment. Through the proposal below, steps are outlined that can be taken to ensure this success.

Proposal for Policy Level Actions

Environment Canada can encourage environmentally friendly alternatives such as EPR through provisions of qualitative guidance and recommendation by creating a guideline plan or breakdown or through education-based programs [26]. In order for Environment Canada to initiate the proposed action, the public must adhere to the following given set of principles.

- Provide qualitative information, and education opportunities. Environmental Canada must initiate programs, such as the one created in Thailand, to inform potential consumers about the effects their purchased products could have on the environment if not handled, and disposed of correctly, and follow up information about what to do after they have purchased items.

- Create long-term incremental approaches to a more sustainable practice of electronic recycling. Statistically speaking, incremental change is the most successful way to put in place a long-term practice [27]. Therefore, the implementation of programs and educational options should be encouraged over years or even decades, for best possible results.

- Facilitate Access to Environmentally Friendly Options. The notable obligation of a government, specifically environment Canada is to implement environmentally friend alternates, and recommendations, extending beyond education and program resources. It should be ensured that all Canadian citizens will have aces to these alternatives.

- Involve Like-Minded Groups. By involving other groups with similar goals, the policy level actions will likely be more successful through the support, and efforts involved.

Though there are barriers to implementing recommendations within the public sector – such as cost, and political obstacles, including pressure from Canada wide manufacturers, and retailers, whom believe they would be adversely affected if environmentally friendly alternatives were imposed, and consequently affecting them economically if consumer purchasing patterns were to change. Government environmental subsidies could add to this, by encouraging the production of less environmentally friendly alternatives. In order for these concepts to be followed through, and pursued, the efforts must also be present in both legislative and executive branches at federal, state, and local levels.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Leary, K. (n.d.). The World's E-Waste Is Piling Up at an Alarming Rate, Says New Report. Retrieved April 10, 2018, from https://www.sciencealert.com/global-electronic-waste-growth-report-2017-significant-increase

- ↑ Statistics Canada. (2016, May 24). EnviroStatsTrash talking : Dealing with Canadian household e-waste EnviroStatsTrash talking : Dealing with Canadian household e-waste. Retrieved April 11, 2018, from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/16-002-x/2016001/article/14570-eng.htm

- ↑ Needhidasan, S., Samuel, M., & Chidambaram, R. (2014). Electronic waste – an emerging threat to the environment of urban India[PDF]. Journal of Environmental Health Science & Engineering

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Pinchin, K. (2009, June 23). UBC j-schoolers expose digital dumping ground. Retrieved April 11, 2018, from http://www.macleans.ca/education/uniandcollege/ubc-j-schoolers-expose-digital-dumping-ground/

- ↑ Environment Canada. (2017). Basel convention on the control of transboundary movements of hazardous wastes and their disposal. Canada.ca. Retrieved 12 April 2018, from https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/managing-reducing-waste/international-commitments/basel-convention-control-transboundary-movements.html

- ↑ Basel Convention. (2011). Overview. Basel.int. Retrieved 12 April 2018, from http://www.basel.int/TheConvention/Overview/tabid/1271/Default.aspx

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 McClearn, Matthew. (2013). Illegal diversion of e-waste is commonplace. Canadian Business - Your Source For Business News. Retrieved 12 April 2018, from http://www.canadianbusiness.com/companies-and-industries/where-computers-go-to-die/

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 VanderPol, M. (2014, July). Overview of E‐waste Management in Canada[PDF]. Environment Canada

- ↑ About E-Waste and E-Waste Management. (n.d.). Retrieved April 13, 2018, from http://www.nea.gov.sg/energy-waste/3rs/e-waste-management/about

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Kielburger, C., & Kielburger, M. (2017, June 16). Canada's Dumping Its Trash in Another Country's Backyard. Retrieved April 13, 2018, from https://www.huffingtonpost.ca/craig-and-marc-kielburger/canada-manila-recycling_b_5452730.html

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Heacock, M., Kelly, C. B., Asante, K. A., Birnbaum, L. S., Bergman, A. L., Brune, M., . . . Suk, W. A. (n.d.). E-Waste and Harm to Vulnerable Populations: A Growing Global Problem. Retrieved April 12, 2018, from https://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/15-09699/

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 International E-Waste Management Network (IEMN). (2017, November 27). Retrieved April 13, 2018, from https://www.epa.gov/international-cooperation/international-e-waste-management-network-iemn

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Mcallister, L. (n.d.). The Human and Environmental Effects of E-Waste. Retrieved April 13, 2018, from https://www.prb.org/e-waste/

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 India introduces first e-waste laws. (2011, June 20). Retrieved April 11, 2018, from https://www.recyclinginternational.com/recycling-news/3695/research-and-legislation/india/india-introduces-first-e-waste-laws

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 15.7 15.8 VanderPol, Michael. (2018) Overview of E-waste management in Canada. Environment Canada. Retrieved 12 April 2018, from https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2014-08/documents/canada_country_presentation.pdf

- ↑ Irani, A. K., Shirazi, F., & Bener, A. (2016). A critical interrogation of e-waste management in canada: Evaluating performance of environmental management systems. Journal of Leadership, Accountability and Ethics, 13(3), 50-63. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/docview/1888686722?accountid=14656

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 EPRA. (2014) Who We Are. Electronic Products Recycling Association. Retrieved 12 April 2018, from http://epra.ca/who-we-are

- ↑ EPSC. About EPSC. Electronics Product Stewardship Canada. Retrieved 12 April 2018, from http://epsc.ca/aboutepsc/

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Vancouver Sun. (2014). Metro Vancouver companies investigated for unlawful export of e-waste to Asia (with video). Vancouver Sun. Retrieved 12 April 2018, from http://www.vancouversun.com/technology/Metro+Vancouver+companies+investigated+unlawful+export+waste+Asia+with+video/8458219/story.html

- ↑ Vancouver Sun. (2015). Surrey firm and president fined a total of $40,000 for illegal export of electronic waste. www.vancouversun.com. Retrieved 12 April 2018, from http://www.vancouversun.com/news/metro/surrey+firm+president+fined+total+illegal+export+electronic/11112865/story.html

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 Kimono, Joan W. (2009). Hi-tech Yet Highly Toxic: Electronics and E-Waste. Journal of Language, Technology & Entrepreneurship in Africa. Retrieved from https://www.ajol.info/index.php/jolte/article/view/41771/37130

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Nguyen Minh Tue, Kana Katsura, Go Suzuki, Le Huu Tuyen, Takumi Takasuga, Shin Takahashi, Pham Hung Viet, Shinsuke Tanabe. (2014). Dioxin-related compounds in breast milk of women from Vietnamese e-waste recycling sites: Levels, toxic equivalents and relevance of non-dietary exposure, Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. Volume 106, Pages 220-225. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0147651314001973

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 World Health Organization. (2016). Dioxins and their effects on human health. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs225/en/

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Igharo, G. O., Anetor, J. I., Osibanjo, O. O., Osadolor, H. B., & Dike, K. C. (2015). Toxic metal levels in nigerian electronic waste workers indicate occupational metal toxicity associated with crude electronic waste management practices. Biokemistri, 26(4)

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 Kiddee, P., Naidu, R., Wong, M. (2013). Electronic waste management approaches: An overview. Waste Management, 33(5), pp. 1237-1250. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2013.01.006

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 Vakilian, B. (2014). Canada’s trade flows of electronic waste: Maps and trends. ProQuest. Retrieved from https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/docview/1845327579?pq-origsite=summon

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Dewis, G., & Wesenbeeck, P. (2016). Trash talking, dealing with Canadian household e-waste. Statistics Canada. p. 3. Retrieved from http://publications.gc.ca.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/collections/collection_2016/statcan/16-002-x/14570-eng.pdf

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Kumar, A., & Holuszko, M. (2016). Electronic waste and existing processing routes: A Canadian perspective. ProQuest, 5(4). doi:10.3390/resources5040035

- ↑ Environment Canada. (2017). Environment and Climate Change Canada - Sustainable Development - Roles And Responsibilities. Canada.ca. Retrieved April 11, 2018, from https://ec.gc.ca/dd-sd/default.asp?lang=En&n=2B69A14A-1