Course:ASIA355/2023/Unearthing Humanity in Turmoil: A Comprehensive Examination of Red Sorghum

Unearthing Humanity in Turmoil: A Comprehensive Examination of Red Sorghum on Visual Power and Cultural Significance

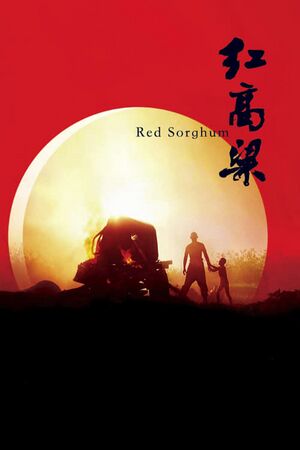

《红高粱》Red Sorghum (1988)

Group Members' Contributions

| Category | Contributors |

|---|---|

| Introduction | D W |

| Stories Behind the Film | R W (Major), D W(Partial) |

| Histories of the Film’s Reception | D W(Major), R W(Partial) |

| Scholarly Literature Review | D W(Write all the summaries into Scholarly Literature Review)

Y X(Intermedial Performativity: Mo Yan's Red Sorghum on Page, Screen, and In-Between) R W(Red Sorghum: A Search for Roots) |

| Comparative Analysis | Z W, S Q |

| Alternative Interpretation | D W |

| Conclusion | Y X |

Introduction

Synopsis

Red Sorghum is a 1988 Chinese film directed by Zhang Yimou and starring Gong Li and Jiang Wen. It is based on the first two parts of the novel Red Sorghum by Nobel laureate Mo Yan. The film's story unfolds during the Second Sino-Japanese War in a rural village in Shandong province, told through the eyes of the protagonist's grandson, recollecting his grandmother, Jiu'er. Originally a poor village girl, Jiu'er is arranged to marry an elderly leper, Li Datou, who is the owner of a sorghum winery.

On Jiu'er's wedding day, the wedding procession is ambushed by bandits while crossing a field of sorghum. Luckily, one of the worker manages to fend off the bandits, ensuring Jiu'er's safe arrival at the winery. However, on Jiu'er's way home, a masked bandit emerges attempting to kidnap her. When he removes his mask, Jiu'er recognizes him as the worker who saved her earlier, and she ceases to resist, beginning to harbor feelings for him. Returning to the winery, Jiu'er finds Li Datou has died under mysterious circumstances. The workers suspect foul play, but no evidence is found. With no heir, the ownership of the winery falls to Jiu'er. She spurs the workers to embrace the wine-making with new vigor. Her lover, the narrator's grandfather, drunkenly declares his affection for Jiu'er to everyone, leading to an awkward expulsion from the room and subsequent confinement in a wine barrel for three days. Soon after, Jiu'er is kidnapped by a band of bandits who demand ransom from the winery workers. After his three-day confinement in the barrel, the narrator's grandfather witnesses a maltreated Jiu'er. He courageously confronts the bandit leader, asking if he violated Jiu'er. The leader denies it, as Jiu'er revealed her relations with Li Datou. Upon his return, the narrator's grandfather urinates in four barrels of wine, which are discovered by Luo Han to surprisingly taste better, boosting the winery's business. Yet, Luo Han decides to leave the winery.

War breaks out, and the Japanese troops invade. Luo Han is tortured and killed by Japanese soldiers. Jiu'er rallies the workers to avenge Luo Han. They hide in the sorghum fields, planning to ambush a Japanese military vehicle. Due to hunger, they send Jiu'er with food for everyone. As she arrives at the field, the Japanese troops also arrive, and she is shot down. The workers detonate the vehicle, killing almost everyone. Only the narrator's grandfather and father survive.

The film premiered at the Berlin International Film Festival on February 12, 1988, where it won the Golden Bear Award.

Roadmap

- An introduction and synopsis of the film

- Stories behind the film looks at the production history and anecdotes related to Red Sorghum, providing context for the film.

- Histories of the film's reception traces how the film was initially received in China and abroad, and how its meanings have evolved over time.

- The scholarly literature review summarizes key themes that scholars have studied in Red Sorghum, including:

- Visual symbolism: Zhang Yimou's use of visual symbols like color, rituals, and imagery to convey deeper meanings and critique society.

- Portrayal of female characters: How the film portrays Jiu'er as an independent woman who rebels against traditional gender roles and patriarchal oppression.

- Counterculture spirit: How the film's themes of individualism and defiance reflect the counterculture spirit that challenged authority in 1980s China.

- The comparative analysis focuses on comparing Red Sorghum with the film Dragon Seed in terms of cinematography techniques, camera angles, and color symbolism.

- The alternative interpretation presents an alternate reading of two scenes that challenges common scholarly interpretations of the film.

- The conclusion summarizes the main points of the film review and overall assessment of Red Sorghum.

Stories Behind the Film

Cast and Crew

Zhang Yimou first emerged into the international cinematic scene with his stunning directorial debut. Before stepping into the director's shoes, Zhang was well-known for his work as a cinematographer, collaborating with prominent fifth-generation directors such as Chen Kaige and Tian Zhuangzhuang. Zhang's transition from cinematographer to director was the novellas of acclaimed Chinese author Mo Yan. The intricate narrative details and insightful depictions in these works inspired Zhang to conceive his own film.[1]

The film was also Gong Li's first leading role. She was a student at the Central Academy of Drama when Zhang Yimou discovered her and cast her as the female protagonist, Jiu'er. She later became Zhang's muse and collaborator in many of his subsequent films, such as Ju Dou, Raise the Red Lantern, The Story of Qiu Ju, and To Live.[1]

Shooting

The film was shot in the rural town of Gaomi, located in Shandong province. Gaomi was both the setting of Mo Yan's novellas and his hometown. The filmmakers constructed a fully operational winery from the ground up, and even planted expansive fields of sorghum, ensuring that the physical setting mirrored the rich and vivid world described in Mo Yan's literature. Adding another layer of authenticity to the film, local peasants were hired as extras. Zhang and his crew guided these locals, teaching them how to act and integrating their naturalistic performances into the film. .[2]

The film faced many difficulties during the shooting process, such as bad weather, a lack of funds, equipment failures, and censorship issues. The filmmakers had to improvise and adapt to the changing situations. For example, they used real blood from slaughtered pigs to create realistic effects for the scenes of violence and war.

Original & Adaptation

The films screenplay was based on the novel of the same name by Chinese author Mo Yan. In 2012, Mo Yan was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. The Swedish Academy awarded him the prize as an author "who with hallucinatory realism merges folk tales, history and the contemporary".[3]

In creating the film, director Zhang Yimou transformed minor novel details into major on-screen moments. He also reduced a 60,000-word script to a 20,000-word narrative, encouraged by author Mo Yan's endorsement to reimagine the source material boldly. Notably, Zhang turned a brief 'palanquin shaking' event into a memorable five-minute cinematic sequence from the novel.[4]

Censorship

The film was initially banned by the Chinese authorities for its depiction of sexuality, violence, and anti-Japanese sentiment. It was only after it won the Golden Bear in Berlin that it was allowed to be screened in China. However, it still faced criticism from some conservative critics who accused it of being vulgar, sensational, and unpatriotic.[5]

Histories of the Film’s Reception

Commercial Success and Initial Reception

The film was a commercial success in China and abroad. It broke box office records in China at that time and earned more than 40 million yuan (about 5.5 million US dollars). Based on the estimated price of movie tickets at the time, about 200 million (times) viewers went into the cinema and watched the movie. It also received rave reviews from international critics and audiences, who praised its artistic style, emotional impact, and cultural significance.

Positive Reception and Impact in China

The reception of Zhang Yimou's Red Sorghum has been overwhelmingly positive, though it has evolved and become more nuanced over time. Red Sorghum's Chinese premiere in 1987 was met with enthusiasm. Audiences were thrilled by its visual style and unconventional storytelling, in stark contrast to the socialist realism of the time. Zhang's vivid portrayal of rural China and the use of the sorghum field as a symbol of resilience and national spirit resonated deeply with audiences who were recovering from the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution. Therefore, it was lauded as a pioneering work that revolutionized Chinese cinema. Contemporary reviews praised Zhang's "lavishly colorful mise-en-scène" and "virtuoso manipulation of theatrical spectacle."[6]

Criticisms and International Recognition

Some exiled Chinese intellectuals, however, were more critical. They argued the film promoted nostalgic escapism rather than meaningful political commentary, with its simplistic celebration of rural life clashing with China's socialist reality.[7] Despite criticisms, Red Sorghum was an undeniable commercial success. Its 1988 premiere at the Berlin Film Festival, where it won the Golden Bear, further boosted its international profile. Western critics applauded Zhang's "highly original and imaginative blend of aesthetic and political revolt." Some, however, viewed the film through an exoticizing Orientalist lens that objectified Chinese culture.[6]

Changing Reception Over Time

Over time, the film's reception has evolved. By the 1990s, post-Tiananmen China had moved into a more nationalistic era, and the once-celebrated themes of individual struggle began to seem at odds with the new cultural climate. Nevertheless, the film retained its significance for its groundbreaking role in Fifth Generation cinema.[8]

Recent Reevaluation and Scholarly Interpretations

In recent years, the film has been reevaluated, scholarly appreciation of Red Sorghum has deepened. The film is now widely considered a landmark work that showcased Zhang's talents.[9] Scholars have provided nuanced interpretations of its politically charged themes. Red Sorghum is seen as representative of the counterculture spirit that challenged social norms in 1980s China, albeit in an indirect fashion.[9] The portrayal of Jiu'er as an independent "new woman" has also come to be seen as a radical statement for its time, with her defiance of tradition resonating with contemporary feminist thought.8[10] The film's symbolism and ritual performances have likewise garnered new scholarly attention.

In summary, while initially seen as aesthetically groundbreaking, Red Sorghum is now appreciated for its complex social critiques and cultural symbols. Though critiqued for political vacuousness in its early reception, the film's ambiguous treatment ofhistory and tradition is now interpreted as a mode of artistic dissent within a repressive sociopolitical environment.[9] Red Sorghum's status as a Chinese cinema classic has thus been cemented even as its meaning has evolved and grown more nuanced over time.

Scholarly Literature Review

Zhang Yimou's 1987 film Red Sorghum has been widely studied by scholars. The film is seen as an example of Zhang's visual and aesthetic style that utilizes folk culture and rituals to portray rural Chineseness.[11] Scholars have analyzed how the film appropriates symbols and rituals from the source novel to create powerful visual effects through color and images.[12] Red Sorghum has also been examined in the context of China's counterculture movements in the 1980s and the portrayal of new, independent women in rural areas.

Visual Style and Use of Ritual

Some scholars focus on Zhang's visual style in Red Sorghum and his use of rituals, color, and images. Some argues that ritualistic scenes in the film "can entertain, as if Zhang were putting his camera in front of a real stage, recording some performance." and analyzes how visual and aural components convey meaning and metaphor in the film, for example through the use of suona horns and drums in key scenes.[13] They discusses how Zhang appropriated and visualized symbols from the novel, like the image of yellow earth instead of black earth in the novel.

The Use of Color

The use of color, particularly red, is a key theme in analyses of Red Sorghum. For example how red takes on different meanings, from sorghum and wine to symbols of passion and vitality, how the color of Red Sorghum changes to correspond with plot and mood. Scholars also argues that Zhang infused emotional tones into a rich red atmosphere to show vitality and free spirit.[13]

Portrayal of New Women

Some analyses focus on the portrayal of Jiu, the main female character, and how she represents a new image of rural Chinese women. Such as calls Jiu "an embodiment of new women's subjectivity" who initiates the male gaze and rebels against oppression, notes that Jiu takes over as winery owner, seeking independence like men, situates Jiu within discussions of new Chinese women in the 1980s.[9]

Relation to 1980s Chinese Counterculture

Red Sorghum has also been examined in relation to China's counterculture movement in the 1980s. Some argues the film promotes individualism that resonated with the rise of individualism in the 1980s.[9] How the film's critique of patriarchy and feudalism awakened audiences to their primal instincts. The folk songs in the film reflect a spirit of defiance and individualism.[13]

In summary, scholarly analyses of Red Sorghum have focused on Zhang Yimou's visual style, appropriation of rituals from the novel, use of color symbols, portrayal of female characters, and relation to China's 1980s counterculture. The film has been seen as searching for "grass roots" Chineseness through folk culture and rituals that challenge traditional notions of Chinese culture.

Comparative Analysis

Why We Choose These Two films?

In the modern history of China, Chinese generations have experienced various remarkable wars, social transformations and national independence. Even in the midst of all the unknown, Chinese people never stopped s working hard to pursue national rejuvenation. All sorts of dramatic social changes are meant to happen so fast that younger generations nowadays gradually forget a lot of significant historical events. Consequently, many directors are working on the creation of ambitious war films as an alarm bell to remind the future generation to reflect on our nation’s past, so that we can build a better future. The film Dragon Seed and Red Sorghum both depict kind-hearted Chinese peasants who live in small villages against the Japanese devil during the anti-Japanese war period, and their Chinese fearless spirit is the main characteristic the directors would like to praise. In terms of the selection of the films, both films highlight the miserable cruelty of the war. Besides, audiences may have different views from East and West perspectives.

Awakening of Feminine Consciousness

Dragon Seed is a war film produced in America, it discusses WWII-era circumstances in which the Japanese attacked Chinese villages. A young woman named Jade Tan, who has her own steadfast belief and independent spirituals, leads the whole village to survive from the enemy. In the film, Jade lives in a male-traditionalist society, where women are never offered opportunities to attend school for studying since the old traditional concept insists that women are originally supposed to stay at home, do the needlework and cook for their husbands and children. However, Jade is provident; she defies others and keeps acquiring knowledge to enrich herself and even taught herself how to use all kinds of weapons properly. She is both physically and mentally well-prepared for a great victorious battle , and that is also why there is no fear in her eyes when the enemy threatens her. Meanwhile she is also the only one who stands up and has the courage to fight for her country . Especially under the American director Jack’s camera, Jade has successfully shaped a figure of fearless Chinese female peasant . Yet it is those details in facial expressions that makes Katharine Hepburn accessible to the audiences because the director makes her more like us.

Red Sorghum is also a war film which illustrates a historical heroic act that occurred in a small village in China. Just like Dragon Seed, Red Sorghum also has a brave female character — Jiu Er, who has her own feminine consciousness and is not likely to follow the rules of the old society. In the film, the Japanese enemy killed Jiu’Er friend Luohan who used to work for the sorghum wine distillery. Jiu’Er leads all her workers to take revenge on the Japanese enemy. Director Zhang depicts a strong-willed Chinese woman who is audacious about anything. In both films, female characters are using their own way to prove that women are not worse than men, they have the ability to independently thinking, and they can be in control of their own destiny. The beginning of the awakening of feminine consciousness during the war period is completely expressed.

Film Setting

In terms of the film set, Dragon Seed and Red Sorghum greatly restore the feudal society of China, including furniture, clothing, farming methods and a lot of traditional Chinese elements in the house, such as couplets, window paper-cut and chopsticks. In Dragon Seed, there are a few scenes that show the Chinese characters. For example, the book that Jude read is a Chinese book named “All people are brothers,” which even appears as the ancient China traditional upright reading method. Also, when the Japanese soldier arrived, the patriotic manifesto was everywhere in the village. Compared to Dragon Seed, director Zhang uses very close-to-life Chinese traditional elements in his film. For example, at the beginning of the film, there is the red sedan which ancient Chinese used to carry the bride, window paper-cut which signified an expression of enthusiasm for the events or new year. These seem causal decorations naturally blend into the film, which easily brings audiences into the character.

Voice Over

Additionally, the narrative techniques used in both films are quite similar. In Red Sorghum, the director uses the voice-over sound effect to narrate from the perspective of the protagonist’s grandson. Using such sound effects to tell his grandparents’ story creates a sense of cordiality in the audience, besides, From the point of view of the protagonist’s grandson, which brings the message to the audience that after killing the Japanese soldiers, the narrator’s grandfather and father are well-lived and raised the several generations. Dragon Seed also uses voice-over in the film. The narrator is introducing the current situations in the film. Because the storyteller always explains the film set, the audience can empathize with the characters in the film.

In order to deeper compare two films, the difference between them are worth to explore as well.

Color

The first one is about color use. In Red Sorghum, Zhang Yimou used bold colors while the film Dragon Seed is black-and-white. Red is the primary color in Red Sorghum. It reflects on some traditional props with meaningful reasons. For instance, the red sedan and red marriage costumes are essential in an ancient Chinese wedding. They represent the auspicious and festive atmosphere, the most beautiful memory of the red color handed down from ancient China.

On the other hand, this representative color can be the double-sided meaning. As the color of human blood, red also represents cruelty, blood and despair. In the film, due to Japanese aggression and bloodlust, innocent Chinese farmers died under their cruelty. Corpses that had been skinned alive were stained with red blood, which become a symbol of terror. At the same time, as Jiu 'er died on the way to deliver food to Yu Zhanao and others, read here is not only the color of blood but also represents the enthusiasm of the Chinese peasant people for the revolution and national integrity in the war of resistance.

Compared to the film Dragon Seed, it only shows a black-and-white style. Because the film was released in 1944, this black-and-white gray picture fits the historical background that was shot during the Anti-Japanese War. Moreover, it also represents the actual photographic techniques in the film industry of that era. This image seems more realistic which allowing the audience to authentically experience the sense of passing the time and getting closer to that period of history.

In addition, it accurately portrays the authentic atmosphere of wartime China. Providing a sense of desolation to the audience since the story focuses on the bottom level of Chinese people, reflecting the hardship of survival. In other words, that is a black-and-white generation for all Chinese people.

Shots and Scenes

The second one relates to the shots and scene setting. Since Zhang used sorghum as the symbol to lead the whole film, there are many scenery shots of the sorghum field. When the hero and heroine are together, a scene of green sorghum swaying slightly in the sorghum field reflects that life represents a new hope. Jiuer's body was spread out, and Yu Zhanao who is “my grandfather” from the voice over knelt beside her in the sorghum field that was flattened by him, reflecting the bold pursuit of love, and they do not afraid of feudal ethics. This kind of wide-angle lens harmoniously merges the environment and characters.

In addition, the wide-angle lens can be given cultural meanings and national characteristics. The director uses several large panoramic pictures to show the endless Loess plateau, including the flying yellow sand and the rugged road. At the same time, the characters appear insignificant in this barren and harsh environment. Adding wild folk songs and passionate "dances" in this national characteristics scene constitutes a wonderful contrasting picture full of praise for life and symbolizes the wild, simple and unrestrained character of the people here.

Compared to Dragon Seed, the shots seem narrower by using telephoto lens. Most of the scenes happen in the same countryside, except very few are in the village. All the settings seem artificial; the characters' routes and the location where the story takes place are fixed. Most of the shots are medium shots that focus on the conversation between characters and their body movements to build their relationship. Due to the tight and intense plot, only a few are master shots in every intense or turning part.

Background Sounds

The third one is the background sounds. In Red Sorghum, most background sounds are traditional music consisting of national musical instruments, including Erhu, Suona and Pipa, which are used to show China's regional charm. The film impresses people with the song "Sister you boldly Go forward," which appears many times in the film, and there is a particularly representative scene: After the battle between Yu Zhanao and the Japanese, in a blood-red background, a sorghum field once again resounded Yu Zhanao's singing. His expressionless singing reflects his deep love for his wife and his wife's departure from his heart. The song with the swaying of the sorghum, as if Yu Zhanao sent his wife's soul home, also reflects the loneliness of his heart and hatred of the Japanese. This music also represents the hero and heroine's challenging love experience, and the last appearance of this song at the end of the film turns from the beginning to the end of their relationship.

Compared to Dragon Seed, only a few scenes have been connected with sound effects. The most common soundtrack in this film is March of the Volunteers. This music is the most representative of China's national conditions at that time. This song has taken place three times. The first time is the English version when the heroine Jade's revolutionary consciousness has been encouraging and awakened, representing the image of progressive thought and up-and-coming woman. The second time is the scene when she and her husband meet some revolutionary people and try to help them, which is the turning point of the main character's destiny. The final scene of this song occurs when they finally find their way to go and persuade; at this time, the music is only the accompaniment, representing that the revolutionary spirit has already merged with their lives. Moreover, some intense scenes have sound effects with dramatic and Western musical styles to emphasize the plot as the turning point and create a tense atmosphere.

To sum up, Dragon Seed and Red Sorghum reflect different point of view from Eastern and Western. This comparison is better for audience to obtain multiple thoughts in a critical way. Particularly for two different films but with similar historical background deserve deeply research by analyzing their various film making methods.

Alternative Interpretation

Scholarly literatures on Red Sorghum often interprets the film as celebrating individualism, rebellion against tradition, and a "return to the grassroots." While these themes are present, an alternative opinion may argue that the film's portrayal of liberation is more complex and even troubling. A close reading of following two scenes from the film may reveals a different point of view.

Scene 1: Jiu and Yu's "Bed" of Sorghum (17:30-20:53)

After Yu carries Jiu into the sorghum field, they have sex amidst the swaying stalks. Scholars portrays this as an act of liberation, rebellion and passion.

The image shown, however, reveals a more ambivalent portrayal. Jiu does not show a happy facial expression. Her lifeless stare and limp posture may suggest a lack of true passion. The low angle of the shot conveys a sense of imbalance, instability. Even the swaying sorghum seems menacing rather than freeing. And considering that the two didn't say a word in the process, Jiu'er's failure to resist at this time does not necessarily mean that she likes what's happening, but may just accept it obediently. In that case Yu's behavior can still constitute rape. This kind of sexual intercourse without confirming the will of women has turned sorghum into a high wall covering criminal behavior.

Scene 2: Workers Singing and Drinking the Newly Brewed Sorghum Wine (48:30-50:40)

This pivotal sequence shows the workers singing and drinking the newly brewed sorghum wine. Scholars have highlighted the ritual's celebration of the carnal and Dionysian spirit.

However, a closer look reveals a different opinion. While the men seem joyful, when they drinking, the sorghum wine flowed in front of the chests of the mens, almost like blood flowing.

This suggests that while sorghum wine brings an sense of liberation and courage, but in reality, they can't be as real as "see the emperor and don't kowtow" as they sing in the lyrics and have the same health as described in the lyrics, especially considering that alcohol is addictive, it is the opposite of freedom. This interpretation can be regarded as revealing how their supposed freedom is an illusion and it's not true liberation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Red Sorghum is a groundbreaking Chinese film directed by Zhang Yimou and starring Gong Li and Jiang Wen. The film, set during the Second Sino-Japanese War, tells the story of a rural village in Shandong province and has been widely praised for its artistic style, emotional impact, and cultural significance. The general perception of the film by both audiences and critics has been overwhelmingly positive, with many lauding its vivid portrayal of rural China and its use of the sorghum field as a symbol of resilience and national spirit.

However, some exiled Chinese intellectuals criticized the film for promoting nostalgic escapism rather than meaningful political commentary. Despite these criticisms, Red Sorghum has been a commercial success and has received numerous awards, including the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival. Scholarly interpretations of the film have focused on its visual style, use of color, portrayal of female characters, and relation to China's counterculture movement in the 1980s.

By comparing with Dragon Seed which also depicts the struggles of Chinese peasants against the Japanese during the anti-Japanese war period, to compare with Red Sorghum in order to gain more insights from films made in different cultural contexts. Both films highlight the Chinese peasants' fearless spirit and their struggle against the Japanese, but they employ different cinematography techniques to showcase various perspectives from Eastern and Western viewpoints, emphasizing the importance of understanding multiple perspectives in film analysis.

Red Sorghum initially garnered acclaim for its aesthetic innovation and vivid depiction of rural China. Despite early criticism for its perceived political vacuity, contemporary scholarly interpretations have lauded its complex social critiques and cultural symbols. It is a powerful and visually stunning film that effectively demonstrates Zhang Yimou's directorial prowess. The film's exploration of themes such as individualism, rebellion against tradition, and the portrayal of strong female characters make it a thought-provoking and engaging viewing experience. Red Sorghum brings to life an authentic portrayal of rural Chinese life during a crucial period of history, showcasing the potential heights of Chinese cinema. Its emotionally impactful scenes and layered social commentary enhance its worthiness for audiences interested in visually rich international cinema, Chinese culture, and intricate social discourses. Red Sorghum is a classic of Chinese cinema that consistently resonates with audiences and critics alike, marking it as a film worthy of consideration and discussion. Overall, this film is highly recommended to those who appreciate cinematic artistry interwoven with historical and cultural exploration.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Zhang, Yue (17 Aug. 2005). "Red Sorghum: That Magical Sorghum Field". Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Tian, Bochuan (10 Dec. 2012). "Memorabilia: Mo Yan Sweden Tells the behind-the-Scenes Story of the Movie 'Red Sorghum'". Chinanews. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Yan, Mo (Sat. 17 Jun 2023). "The Nobel Prize in Literature 2012". THE NOBEL PRIZE. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Song, Yusheng (May 9. 2019). "Mo Yan Remembers Zhang Yimou's Adaptation of Red Sorghum". Chinanews. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Khazan, Olga (October 11, 2012). "Mo Yan, a Nobel winner China can get behind". The Washington Post.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Chow, Rey (1995). Primitive Passions: Visuality, Sexuality, Ethnography, and Contemporary Chinese Cinema. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231076838.

- ↑ He, Chengzhou (2014). "Rural Chineseness, Mo Yan's Work, and World Literature". Mo Yan in Context: Nobel Laureate and Global Storyteller: 77–92 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Singh, Paisley (28 February. 2013). "Perspectives in Flux: Red Sorghum and Ju Dou's Reception as a Reflection of the Times" (PDF). Institutional Scholarship. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 He, Chengzhou (2020). "Intermedial Performativity: Mo Yan's Red Sorghum on Page, Screen, and In-Between". Comparative Literature Studies (2020). Volume 57, Issue 3: 433–442.

- ↑ Lau, Jenny (Winter 1991–1992). ""Judou". A Hermeneutical Reading of Cross-Cultural Cinema". Film Quarterly. Vol. 45, No. 2: pp. 2-10 – via JSTOR.CS1 maint: extra text (link) CS1 maint: date format (link)

- ↑ He, Chengzhou (2020). "Intermedial Performativity: Mo Yan's Red Sorghum on Page, Screen, and in-between". Comparative Literature Studies (Urbana). vol. 57: pp. 433-442 – via Project MUSE.CS1 maint: extra text (link)

- ↑ Neo, David (2003). "Red Sorghum: A Search for Roots". Senses of Cinema. vol. 28.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Ng, Yvonne (Spring 1995). "Imagery and Sound in Red Sorghum". Kinema: A Journal for Film and Audiovisual Media – via Open Journals.