Course:ASIA355/2023/Film: 英雄(Hero)- Zhang Yi Mou (2000)

英雄(Hero)- Zhang Yi Mou (2000): Exploring Perspectives on the Political, Military, and Gender Portrayals

Group Members' Contributions

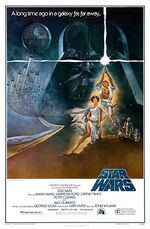

Mathew Lee : Introduction. Stories Behind the Film, comparative analysis (Star Wars) and 1st part of Scholarly literary review, and Alternative interpretation.

Yize Zhao: Histories of the Film’s Reception, Scholarly Literature Review (the 2nd part), Alternative interpretation (the 2nd part), and Conclusion.

Introduction

The film Hero is directed by Zhang Yimou and released in 2002. The movie tells an alternate history set in ancient China during the Warring States period. With its spectacular cinematography, delicate mise-en-scene, and exceptional martial arts action scenes, Hero has become a landmark film in Chinese cinema.

The film revolves around the flashbacks of the protagonist, Nameless, a skilled swordsman of Qin Kingdom. Nameless claims his award for killing three threatening killers of Emperor Qin: Broken Sword, Sky, and Snow. As a reward, Nameless grants a confrontation with the Emperor within 10 steps close. Emperor quetions Nameless how he manages killing the three assassins. From the flashback of Nameless's storytelling strategy of killing the three threatening killers, the Emperor realizes that Nameless did not kill those three assassins but was on a mission to assassinate the Emperor himself. The characters' intricate motives and intertwined relationships are unveiled through flashbacks and revelations, Leading to a climax that challenges the boundaries of loyalty, love, and sacrifice. The director, Zhang Yimou, is known as one of the most famous directors in China and Worldwide as well; Hero showcases various mise-en-scenes and choreography that even make the viewer enjoy the movie.

In this Wiki project, we will explore two scholarly perspectives: the criticism of the political and military portrayal in the film Hero and the argument surrounding its gender portrayal. Additionally, we will provide two scholarly articles, offering a more comprehensive understanding of the film. By examining the scholarly analysis of Hero's political and military portrayal and analyzing its gender representation, we aim to provide an alternative interpretation that will provide different viewpoints to study a deeper understanding of the film.

Furthermore, we have discovered similarities between Hero and the Star Wars series. Through a discourse on cinematic and thematic analysis, we will compare and contrast these two movies, discourse into their similarities and differences.

Stories Behind the Film

Budget and Hong Kong Production

Hero, the first Chinese movie released in the North American market, had a total budget cost of 31.1 million dollars. Despite a two-year wait for its release, Hero generated a worldwide profit of 177 million dollars.[2]The film featured renowned cast members including Jet Li, Tony Leung Chiu-wai, Maggie Cheung, Zhang Ziyi, and Donnie Yen. The budget, which was also supported by Hong Kong production, allowed director Zhang Yimou to bring in famous movie stars from Hong Kong. Since Jet Li and Tony Yang are from Hong Kong, several Mandarin revoicing throughout the movie made the tone and acting more vivid and sincere. Many critics asserted that Maggie Cheung's voice-over recordings made her sound like 'Macbeth.'[3]

Translation of Tiānxià (天下) in Global Version

The film has faced criticisms regarding its translation for the American release, particularly regarding the central concept of Tiānxià (天下), which directly translates to "Under heaven" from direct translation. Tiānxià (天下)conveys the idea of "the World," with historical context, the entire China states. Interestingly, when the film was released in Belgium two years before its U.S. release, the subtitled translation of Tiānxià viewed as "all under heaven." However, for the American audience, the translation was localized to the two-word phrase "our land," which suggests a narrower interpretation limited to the nation of China rather than encompassing the entirety of the world. Some critics consider this discrepancy raises questions about Zhang Yimou's original intention and whether the film was intended to convey a message about the world and global unity.[4]

Histories of the Film’s Reception

Being an internationally successful film, Hero has elicited hot debate since its 2002 airing in China and its 2004 global release. With the themes of “family”, “national unity”, “love”, “sacrifice” and “all-under-heaven”, the director Zhang Yimou presented the world a piece stunning in color, dramatic and choreographic in physical movement, and generous in its use of A-list actors and budget. The audience, no matter domestic or abroad, have been mesmerized by this innovative Chinese film (it was the first Hollywood-scale Chinese film ever shot) that the film broke the box record in China and topped the box office in the United Stated for two weeks. Because of the wide acceptance of the film, the Chinese government, for the first time in history, allowed its national media CCTV to air the Oscar ceremony of the year in which Zhang Yimou and his team were present.[5] TIME Asia, seeing the success of Hero, commented that the hope of Asia rests on this film.[6]

As good as the film has been accepted, the debates it has aroused are also unprecedented. In China, the most well-known Chinese film-rating platform Douban gives the film, until the date of 18 June, 2023, a 7.6 score out of 10.[7] The majority (out of more than 300,000 commenting viewers) gives the film a four star or a three star in a five-star rating mechanism, while commenting how the film is less than expected. For the Chinese audience, a main let-down is its void of a persuasive theme and character development. One has commented that the so-called heroes, Nameless, Broken Sword, Long Sky, Flying Snow or the King of Qin, are more like symbols than real people with flesh and blood. At the beginning, the assassins’ hatred toward King of Qin (for his brutality) has made them machine-like people who practiced sword skills ten years as if a single day, yet, they gave up their effort easily, only because of a seemingly glorious pursuit of “all under heaven”, which, according to the film, could only be achieved by King of Qin because of his high ambition to unite China and create peace. In other words, the assassins are all persuaded by the logic that Qin, through its temporary killing and taking from other countries assets, people and lands, could eventually bring peace and greater good to the world. In the eyes of some Chinese viewers, the logic is like “opening doors for the fascist Japanese during World War II and begging them to liberate the country for the greater good of Asia.”[8] Despite the critiques, the film’s rating has gone higher and higher over recent years. One possible explanation is that China’s decreased content quality has prompted many to re-watch old movies, which, though have their shortcoming, are still better than what is created nowadays.

Compared with the Chinese audience, the film’s reception in the Western world seems like a better case. In IMDB, the film has reaped a score of 7.9/10,[9] while that in Rotten Tomato is as high as 87/100.[10] Though some are drawn to the film’s Zen style and martial arts, namely the Oriental elements that allured many since the time of Bruce Lee, some others also offered heavy criticism toward the film’s implicit endorsement of the authoritarian ideology promoted by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)-led China. In a scholarly review by Xiaoming and Rawnsley,[5] the fllm’s taking on “peace” coincides with the Chinese leadership’s worldview of “peaceful-rise”, where the question of whether peace could really be achieved is cast into doubt. The film becomes more political problematic to the Western world considering CCP’s history of persuading its people the necessity of sacrificing their individual good for national development.[11] In fact, Zhang himself had admitted in a 2007 interview that he wanted to create something “Hollywood”, while having it accepted by the CCP who regulated tight censorship over cultural artifacts.[12] A result of placing the nation over each individual in this film, could be the outside world’s misunderstanding of a real China. This film, just like every other film directed by Zhang, makes small figures petty little beings in front of the powerful, and the powerful an omniscient and almighty being who has everything under control. It shows again that the personal tragedies are self-inflicted by the Chinese people, and a failed result of rebel is because of internal division between the people themselves. De La Garza has commented how the film might cause negative stereotypes for China and Chinese people, as it “impresses people the wrong way."[13] Also, by overly strengthening a culture of nation-over-people, it presents China as a challenge for globalization rather than an inclusive entity that embraces the universality of freedom and personal happiness.

Two reasons could explain the global criticism of the film. For one, the Chinese audience and audience from other places had different cultural awareness. The Chinese people, while knowing that the film is a fiction, could not help but relate the characters with historical figures. For them, despite being the first ruler that shaped China as a nation, the King of Qin is more about a self-obsessed and brutal figure that destroyed people and books without a blink of an eye.[5] Hence, many cannot accept the King of Qin being glorified in the film under the disguise of “all under heaven”. For the Western audience, it is their unfamiliarity of Qin and the Chinese history and culture in general, as well as their hatred over fascist ideologies that once hurt them, that they find the nation-over-people ideology distasteful. For the other reason, the audience in general might have read the film, which is based on a historical story, with a modern eye. In a globalized world where individualism triumphs, the film’s celebrating nationalism certainly becomes untimely and inappropriate. In fact, as much as the film has been advertised (2-million dollars used in marketing alone in China) and the people have been told to not miss it,[14] any let-down could be amplified to become a deadly problem.

Scholarly Literature Review

1) In Wendy Larson's scholarly article, she discusses the film Hero's historical background, which is based on the Warring States period in China and the real historical figure of Emperor Qin Shi Huang of the Qin dynasty. Larson explores the director's intention behind setting the movie's plot in ancient China and examines the critical reactions to the film.[15]

Larson first highlights the characters of Nameless and Broken Sword, the assassins who ultimately understand the emperor's code of "always fighting on behalf of the weak against the strong." These assassins lose their intent to kill the emperor and instead choose to sacrifice themselves in the hope of achieving a unified nation, culture, and people of China. According to Larson, the film suggests that the cultural nationalism which portrayed by the film Hero, represents modern China's self-presentation to the world. Under a communist government, the country could become one unified nation.[15]

Larson's article further emphasizes that "Hero" focuses not so much on the inevitability of authoritarianism but rather on the limitations of culturalism. She asserts that Zhang Yi Mou's perspective of culturalism is based on reflecting people's soul and individual's distinctive cultures. The film symbolizes the idea that a nation requires a powerful state government and a strong military to wield a unified power. It strongly argues against the belief that relying solely one strong cultural foundations can lead to political success. Director Zhang Yimou appears to express skepticism about the effectiveness of multiple culture as an equalizing force. He does not seem to believe in having different cultural perspective, but idealizing one unified vision of peace based on equal simultaneousness among cultures. The film encourages viewers to question whether achieving equality necessitates the exertion of relative force, challenging conventional aspirations for the coexistence of distinct yet equal cultures and languages.[15]

2) In Louise Edwards' article[16] about women warriors in Hero, she offers a critique that Hero's female figures, while being recognized in the film as real women rather than women who cross dress as men, are still subjugated to the patriarchal system where men’s thoughts are considered first. In developing her argument, Louise first introduces the tradition of involving women fighters in Chinese literary works, and then moves on to analyzing how much women in Hero follow the traditional depiction of women in artworks.

From the author’s observation, Flying Snow and Moon from Hero are no different from Hua Mulan and Mu Guiying (both are traditional women warriors who protect their family either for men or along with men) in defensing a patriarchal order. Unlike men in Hero who place Tianxia over everything else, the top priority for women warriors is their family, the continuity of their family and the revenging for their family. That explains why, in front of Broken Sword’s enlightenment over the importance of sacrificing the small for the greatness (unity), Flying Snow chooses to turn a blind eye toward the thought: for her, the death of her father is greater than the philosophical awareness of what a nation is. Similarly for Moon, throughout the film, no matter it is during the imagined scenes or real scenes, she stays loyal to her master Broken Sword. In one scene, she begs Nameless to take Broken Sword’s words, as the latter, in her eyes, is always right. The unthinking words from Moon reveal how she obeys her master without ever independently contemplating about “why the man is right.”[16]

Later, Louise acknowledges how the women are depicted in the film as sexually attractive and active, but she also points out that the women still fall into the common imagination of women being modest. The films three-layered development shows exactly what ideal and acceptable are like: in the faked version, both Flying Snow and Moon are heavily romanticized and use force arbitrarily at wills of love and hate. Especially for Moon, who plays victim and sexually vulnerable to Broken Sword. However, as the lie becomes rebutted by King of Qin, the real women figures are disclosed to the public: they are not fallen, jealous, narrow-minded, but are home-yearning and willing to sacrifice themselves for their men. Just because of her loyalty to two men, her father and her lover, Flying Snow is tortured by the idea of having King of Qin killed and the death of her lover who holds a different view from her own that she finally has herself killed because of her failure on both ends.

In conclusion, Louise noticed the change of women figure’s role in the glocalized cultural product as Hero. The two women, as compared with traditional women figures, are more sexually bodacious and real (woman-like) in their appearance and behavior. However, their storyline still falls into common imagination of women being victims of male desires and male thoughts.

Comparative Analysis : Star Wars and Hero

Comparison 1: Opening Sequence In both Star Wars and Hero, the opening sequences introduce the world and set the stage for the unfolding conflicts. This scrolling text has become an iconic feature of the Star Wars franchise. The movement is known as Star Wars' famously scrolling text that moves from the bottom to the top of the screen, providing essential background information about the conflicts in the galaxy. Similarly, Hero opens with a textual prologue that establishes the historical context and introduces the central conflict between Nameless and the Qin Kingdom. The use of textual exposition in the opening sequences creates a sense of enormous scale and sets the tone for the following epic tales.

Comparison 2: Interestingly, both films utilize the same sequence of portraying medium two-shots and over-the-shoulder shots, allowing the audience to follow the action from the characters' perspectives and enhancing the sense of intensity and immersion. In Hero, Zhang Yimou employs a combination of slow-motion shots, changing screen colours black to colourful, and dynamic choreography to depict the complex and elegant movements of the characters, creating a sense of grace and beauty in sword fighitng. Similarly, in Star Wars, the lightsaber duels between characters like Darth Vader and Obi-Wan are highly stylized and visually engaging, although the effects in the first Star Wars movie, released in the late 1970s, may lack the same level of sophistication in terms of motion and choreography.

Comparison 3: The portrayal of army in both Star Wars and Hero showcase the might and power of their respective armies in different ways. In Star Wars, the soldiers, specifically the Stormtroopers of the Imperial Empire, are depicted in a highly controlled and disciplined manner. The camera is framed the army from tilted angles, and mise-en-scene emphasizing their uniformity and order. The black and white costumes worn by the Stormtroopers further reinforce the notion of an authoritarian and oppressive force, resembling a chessboard which prompts a sense of European imperialism.

In Hero, the portrayal of the army takes a different approach. The camera is framed by a front view of the soldiers, presenting a visually overwhelming sight as they fill the screen. The sheer number of soldiers creates a sense of magnitude and reinforces the idea of a coercive military force. Unlike the Stormtroopers, the soldiers in Hero are not depicted as faceless or uniform; instead, they showcase a variety of colours in their costumes, reflecting the diversity and individuality within the army. This portrayal highlights the collective strength and unity of the army, contributing to the film's themes of a unified government with military power.

Both Star Wars and Hero share similarities in their approach to cinematic techniques and storytelling devices. From the iconic scrolling text, stunning sword fighting scenes and portrayal of powerful armies, these films demonstrate how different filmmakers can draw inspiration from one another while incorporating their unique cinemetic and storytelling skills.

Alternative Interpretation

1) Refuting Larson's Argument: Totalitarian view, and Irony of Qin Dynasty

From Wendy Larson's perspective, Hero does not support totalitarian and authoritarian political view. In order to overthrow the critics of totalitarian view of the movie, Larson asserts that the movie rather has more characteristic cultures having one vision of peace, which makes a unified country. However, there are several scenes, and historical background that refute Larson's idea of denying totalitarian view of the film, and moreover amplify Chinese communist government, which asserts strong political, and hierarchy power as well.

Shot 1 (16:20): Emperor's paranoia

The shot presents an extreme long shot, depicting a dimly lit and somber palace in the mise-en-scène. This creates a heavy atmosphere, evoking a sense of nervousness for anyone entering the space. Notably, the subtitle "within 10 paces of his majesty" reinforces the Emperor's asserting coercive political power, as regular civilians seldom have the opportunity to approach him. This highlights the Emperor's cautious and gloomy disposition, emphasizing his constant vigilance.

Shot 2 (27:56): Zhao calligraphy

The shot features Broken Sword in a long shot with a low angle. The mise-en-scène is saturated with red hues, visible on the walls, Broken Sword's attire, and the calligraphy which represents the Zhao State language. The characters used by Zhao State language differ from the simplified and traditional Chinese characters. Zhao State has its own unique Chinese character system. While Broken Sword is engrossed in writing the calligraphy, his apprentices fall victim to the arrows of Qin's archers. Following this scene, Emperor Qin asserts his intention to work on unifying Chinese characters for everyone.

It is crucial to analyze the mise-en-scène of the calligraphy in this scene. The word is written in red, resembling the color of blood. This conveys a connotation that aligns with the history of Qin, which is marked by the shedding of "blood" from others. From this scene, we can infer that the Qin dynasty and the modern Chinese government share similarities in their histories, characterized by civil wars and numerous deaths.

Shot 3(1:25:03) & 4(1:43:26): One unified Nation, and the Irony of Qin dynasty.

In Shot 3, a close-up shot focuses on Nameless, who ultimately relinquishes his intention to kill the Emperor. He does so because he believes that "only the King of Qin can stop the chaos." Nameless gives up his will to kill the Emperor because he envisions a unified China under Qin's rule, which would result in an end to civil war and fewer sacrifices of both civilians and soldiers. This scene gives the impression of endorsing a totalitarian society, as Nameless, Broken Sword, and the Emperor support sacrificing the few for the greater good of a unified nation. This reflection extends to the current Chinese government, suggesting that the shedding of blood was inevitable, but with the establishment of a unified government, there is now reduced chaos in the country.

In Shot 4, the scene concludes with a view of the Great Wall, symbolizing Chinese identity, and features a script mentioning the Qin Emperor's unification of China into one country. However, the ironic aspect is that the unified Qin dynasty lasted only five years.[27] This situational irony serves the director's purpose, posing a question to the audience: were the deaths of Nameless, Snow, and Broken Sword worth it? This differs from Larson's concept of a unified culturalism in China. Instead, the film portrays the creation of a totalitarian country while simultaneously highlighting the ironic fact that this regime's existence was short-lived.

2) Counter-argument to Louise Edwards' Idea on Female Obdience to Men

Louise Edwards offers her opinions that women in Hero were ultimately subjugated to male desires and male thoughts.[11] Using the feminist lens, she critiques how the figures of Flying Snow and Moon had their minds driven by personal wishes of revenge (for a father) or love (toward a teacher) that they either failed to recognize the importance of having a nation united because the death of a father is more important than the future peace of a nation (as in the case of Flying Snow) or blindly believed in the importance of having a nation united because what a teacher says is unquestionably right (as in the case of Moon). In contrast, the men, mainly King of Qin, Nameless and Broken Sword, grasped the “ultimate” meaning of swordsmanship and the idea of “Tianxia”, with the latter two making an unspoken decision to pardon the King of Qin on his past wrongs and to rely on the King to bring greater good to all. Louise also exaplains how in one of the last scenes, Flying Snow killed herself using the same sword she killed Broken Sword, as if apologizing to her failure on both ends (revenging for father and obeying the lover). In response to Louise’s idea of women being depicted as if some victims who only appealed to men without considering the future of a nation and who tangled indecisively between the loyalty to father and the loyalty to lover, I want to offer my counterargument that the women did care about the idea of nation-building (just in a different way from the men’s), and they had never been indecisive and cared overtly about different men’s opinion (Flying Moon was especially firm about having the King of Qin killed).

Scene 1 (1:08:21-1:12:44):Hurting Broken Sword for the Goal of Killing King of Qin

In the four-minute scene that happens in the bamboo book chamber, Namelss, Broken Sword, Flying Snow and Moon are all togethered under the request of Namelss to kill King of Qin. As their dicussion unfolds, Flying Moon, who had not talked with Broken Sword for years, started picking wrongs from Broken Sword (shot 1) for his giving up his mission when he had every opportunity to kill King of Qin. As she talked, in a non-giving-up voice, the camera which focuses her face in a close shot, transits fastly from her face to Nameless's face and Broken Sword's face. The fast transitions not only disclose their shockedness (upon knowing the fact and Flying Snow's exposure of the fact), but also reveal how Flying Snow is not afraid of "stirring up" something controversial and openly challenging a man who she loves. Later, Flying Snow even asks Nameless to help her hurt Broken Sword, so the latter would lose the ability to stop their mission. Without hesitation, she indeed practices her word: Broken Sword is stabbed in his stomach. If we follow Louise's interpretation of women doing everything for men and succumbing themselves to men, Flying Snow would never hurt someone who is "bigger" in her mind than herself is. Hence, a plausible explanation is that the woman has in her mind her goal and her determination bigger than a man, which all demonstrate her as an woman independent and free in her will. Still later, she is shot closely in her side face, and the depth of field is so shallow that Broken Sword is belittled and out of focus: the woman now is the true hero (shot 2).

Scene 2 (1:33:43-1:39:42): Mis-killing Broken Sword and Real Suicide of Flying Snow

In this scene, Flying Snow and Broken Sword, knowing the failure of Nameless, for the first time in three years, talk to each other in person. After questioning what Broken Sword has told Nameless that the latter gave up his mission to the disappointment of Flying Moon, Broken Sword answers: "Tianxia". The moment Flying Moon uses to process the information (shot 3), and even the asking of what Broken Sword has said, indicate her uninformed knowledge of Broken Sword's mind during these years. This, again, shows how Louise's argument of Flying Snow's inability to take in the philosophy of Tianxia is unreasonable. It is not that she cannot understand, but that she had not the oppurtunity to really understand: it is she herself who shuts the door for communication. Even if Flying Snow shouts to Broken Sword in a later shot "that [Tianxia] is all you care about", it doe not necessary mean she could not grasp the idea of Tianxia. Her words are more like a complaint of her man's believing in a logic that she herself simply does not buy into. To interpret further, her breaking up with Broken Sword over these years is not necessarily about the man's cutting off the possiblity to revenge for her father (one man v.s. another man in Louise's interpretation), but could simply be about her disppointment over the man's not informing her in advance of his decision. During their conversation, the light becomes warmer as they confess to each other, implying their fixed relationship. Later, after Broken Sword gives up arguing and decides to let Flying Snow kill him so that he could have himself explained, Flying Snow decided to kill herself using the same daggar. By killing herself, it is not necessarily that she feels sorry for not beliving in her lover and for not being able to revenge for her father, it is more likely that she is tired of struggling (when all what she loved are gone) and nothing in her mind at that momoent is more important than shrinking into a some place called home. While nagging about "we are going home", the woman and her man are featured in a long distance shot which show how vast the land is yet how small the two persons are (shot 4), in front of a national allegory of unity.

Conclusion

To conclude, Hero, the first Chinese blockbuster, satisfies both the domestic and overseas audience in its imaginary depiction of a group of assassin’s giving up killing a king in exchange for long-term national peace.

The film’s aesthetics, especially its use of color and design of martial art movements, have been widely applauded. If compared with Star Wars, both films are visually engaging in the design physical movements, which are portrayed through various shooting styles. Also, both epically introduced the story background and central conflicts though scrolls of words in the opening scene. While there is a few differences in how they depict the army, both demonstrated collective strength and a sense of magnitude of the troop.

However, critiques also ensue because of its problematic themes of sacrificing individuals for national unity and glorifying a historically brutal king by justifying his cause. Other than its endorsement of totalitarian ideologies (despite how the scholarly writer Wendy Larson refuted the inevitability of authoritarianism), the film also belittles women in a sense that the women, again, are staged as products of male desire.

Despite all the debates, the film is definitely worthy of view, not only because it leads up the market of Chinese blockbusters, but also because it is a way to know China, perhaps not entire accurately, but still with some truths. For Chinese culture lovers, it is a chance to know that Chinese people are unlike Fu Machu. For martial art lovers, it is a chance to know that other than Bruce Lee’s fierce style and Jackie Chan’s funny style, there are also other imaginary territories of fights existent in Chinese artworks. For those with no specific reasons to watch, the film also provides an opportunity to learn about something in the world, that truth is often times not what we see, but something to be scooped out layer after layer.

References

- ↑ "Hero= Poster".

- ↑ "Hero".

- ↑ "Hero".

- ↑ ""Cause: The Birth Of Hero" Documentary".

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Chen, X., & Rawnsley, G. D. (2010). In Rawnsley G. D., Rawnsley M. T.(Eds.), Global chinese cinema: The culture and politics of 'hero'. Routledge.

- ↑ Short, S. and S. Jakes. (2002). Making of a Hero: Expectations are Sky-high for Director Zhang Yimou’s Ambitious Star-studded Martial-arts Flick, TIME Asia 21 January: 44–7.

- ↑ "Hero's rating on Douban". Douban. June 18 2023. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Lao, Zhangtou (19 June 2023). "Review of Hero on Douban". Douban.

- ↑ "Hero's rating on IMDB". IMDB. 18 June 2023.

- ↑ "Hero's rating on Rotten Tomatoes". Rotten Tomatoes. June 18 2023. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ 11.0 11.1 Larson, W. (2010). Twenty-first century women warriors: Variations on a traditional theme. In G. D. Rawnsley, & M. T. Rawnsley (Eds.), Global chinese cinema (pp. 178-194). Routledge.

- ↑ Barboza, David. (2007). A leap forward, or a great sellout?, The New York Times. Available online at: http://www.nytimes.com/2007/07/01/movies/01barb.html?_ r=1&oref=slogin

- ↑ De La Garza, A. (2007). Negotiating national identity on film: Competing readings of zhang yimou's hero. Media Asia, 34(1), 27-32.

- ↑ Wang, T. (2009). Understanding local reception of globalized cultural products in the context of the international cultural economy: A case study on the reception of hero and daggers in china. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 12(4), 299-318.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Larson, Wendy (2008). "Zhang Yimou's Hero: dismantling the myth of cultural power". Journal of Chinese Cinemas.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Edwards, L. (2010). In G. D. Rawnsley, & M. T. Rawnsley (Eds.), Global chinese cinema (pp. 91-103). Routledge.

- ↑ "Starwars Poster".

- ↑ "Obiwan and Darth Vader fighting scene".

- ↑ "Sword fighting scene".

- ↑ "Star Wars opening scene".

- ↑ "Hero- opening".

- ↑ "Hero-Qin Army".

- ↑ "Starwars Imperial Army".

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Zhang, Yi mou. "Hero (2002)".

- ↑ Zhang, Yi mou. "Hero (2002)".

- ↑ Zhang, Yi mou. "Hero (2002)".

- ↑ "Zhou-Qin history".