Course:ASIA351/2021/Shanghai Express (1935)

Shanghai Express (Translated: 平沪通车) is a Chinese novel written by Zhang Henshui originally published in 1935 in the travel journal Lvxing Zazhi (旅行杂志). Later translated into English by William Lywell in 1997. The novel depicts banker Hu Ziyun’s interactions with a mysterious woman named Liu Xichun and their tabooed romantic relationship aboard a train from old Peiping to Shanghai. It is a prime example of the so-called “Mandarin Duck and Butterfly” genre of Chinese fiction, sometimes also referred to as a derogatory term for sentimental love stories that served to “please a wide-ranging reading audience” (375).[1] The novel was initially published in the Chinese Traveler (Lvxing Zazhi ), a lifestyle publication that featured essays, journals, articles, advertisements, and proses on the subject of travel. Although Zhang's works have been criticized for "lacking artistic innovation"[2], many of his works are now praised in academia for their literary styles that were recognized before. The English translated version by William Lywell has often been criticized for lacking Chinese characters to match titles and names in the text and footnotes found in the original Chinese version (378).[3]

| Shanghai Express | |

|---|---|

| |

| Author | Zhang Henshui (author)

William Lyell (translator) |

| Title | Shanghai Express |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Butterfly Fiction |

| Published | University of Hawaii Press |

| Media Type | Image of Book Cover |

Historical background

Shanghai was a modernized and diverse cosmopolitan city in the 1930s. It was a “semi-colonial place ruled by local forces and colonial powers."[4] The colonialism of the Japanese and the Western led to the “institutionalization of capitalist economic structure” of the city (40).[5] This enabled Shanghai to be “comparatively more progressive in terms of modernity” especially with “intellectual and commercial ideas that contributed to Shanghai’s cultural sphere” (40).[5] Shanghai’s modernity is best demonstrated in its mass production and consumption of literary products. The city served as a hub for “intellectuals, scholars, writers, and artists from all over China” to gather and produce literary works (41).[5] Such collaboration has had a visible effect on literary forms through the integration of many different literary traditions. In the book itself, Zhang has attempted to dignify his style through the retention of form and language of the old-style Chinese novel, but “assimilating techniques and content from May Fourth writing in an effort to modernize traditional fiction” (278).[6] Another way that modernity was presented was the “prominence it accorded female characters” (71).[7] A common theme throughout was a positive attitude towards the "new-style" woman, who attempts to a greater or lesser degree to question her traditional role and to assert her individuality (71).[7] However, the romantic style of Zhang often clashed with other progressive writers of the May Fourth Movement, who have criticized his work for being “sentimental entertainment” portraying marital love (278).[6]

Synopsis/Plot Summary

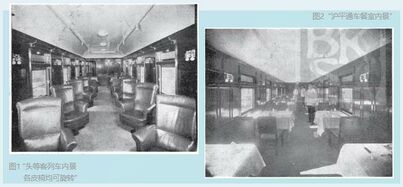

Set in winter of 1935, “a wealthy banker, Hu Ziyun, on the train to Shanghai from Peiping, meets a young lady who introduces herself as Miss Liu, a remote relative of the Hu family” (279).[8] He “is immediately charmed by this fashionable modern woman” and “offers her a berth in his two berth compartment in the first-class coach” (279).[8] Ziyun “is increasingly lured by her beauty and her femininity,” as “she conducts herself like a woman who is clever, amusing, seductive, and ready for a love affair” (279).[8] While Zhang is developing a sensual atmosphere between these two characters, he also “[evokes] the smells of this microcosm of the urban world” when bringing us on board.[9] Zhang allows readers to peer into the lives of passengers in “first, second, and third class cars” through Ziyun and Miss Liu’s frequent journeys down to the other train classes to mingle with friends or old acquaintances.[9] These transitions between classes illuminate the contrasts between social classes in China by revealing “what various travelers wear, their conversations,” and the assorted smells of each compartment.[9]

As the journey to Shanghai progresses, so does the taboo love affair between Ziyun and Miss Liu. The night before Hu and Miss Liu’s arrival in Shanghai, where they have decided they will start their new lives as lovers, the two “spend the whole night eating, drinking and talking" (279).[8] Hu happy, tired and drunk, falls asleep, meanwhile, Miss Liu steals Hu’s fortune of cash and government bonds and off-boards the Shanghai Express. Hu awakes, shocked to learn of Miss Liu’s deceiving scheme and thievery, and soon discovers "she’s a well-known female con artist" (211).[9] "The story ends up with Hu Ziyun, now completely ruined and reduced to a homeless pauper, on his way back to Peiping” (684).[10] Hu evidently is not only robbed of his money, but Zhang robs him of his voice by concluding the last chapter in objective third-person narration to illustrate Hu’s lost identity as a superior citizen of the first-class.[8] Through an ironic turn of events, the story thus masters social commentary on the various inequalities present between status groups in China throughout the development of Miss Liu's long con ‘love affair.’

Main characters

Hu Ziyun

A married mid-level bureaucrat. He transitions from a first class citizen to third class citizen by the conclusion of the story. He has a complete round face, wears a pair of horn-rim glasses and a camel hair gown lined with fine blue silk (3).[9] He is careful about the rules of the train and is insensitive to those of lower classes. He is infatuated with Liu Xichun, and ends up being deceived by her.

Liu Xichun

A left wing progressive worker archetype. She is a seductive modern Shanghai woman who turns out to be a professional con artist. She has a pretty, powdered face, fluffy black hair, with flashing deep black eyes (4).[9] She wears a fur coat, a pair of jade earrings, and a large diamond ring (4).[9] She is generous, elegant, well mannered, has a playful attitude, and is familiar with train-travel.

Li Chengfu

Ziyun’s friend; second-class; a professor. He is described to be straightforward, neat and clean.

Mrs. Yu

A second class, middle-aged woman. She is an alliance of Liu Xiuchun. She has a thin face, full eyebrows, sparkling eyes, and wears a traditional bun on her hair (64).[9] She wears a simple black silk gown with small diamond buttons, and a small pair of earrings fashioned of gold thread (64).[9] She is sensitive to social situations.

Zhang Yuqing and Zhu Jinqing

A newly married couple from third class. Jinqing is Liu Xichun’s friend and former classmate. She is shy and conservative, and her husband, Yuqing, loves and cares for her dearly.

Qi Youming

First class; son of Cabinet Minister Qi. He knows of Xichun and her occupation as he has witnessed her schemes before. He is characterized by owning a Russian wolfhound and stays in the same train cart as Hu Ziyun and Liu Xichun.

Shi Ziming

Hu Ziyun’s former administrative secretary, who transitioned from first to third class. He suffers from poverty, with a gaunt face, unshaved beard, and a battered old felt hat (110).[9] He is described as unconfident compared to when he worked with Hu Ziyun (110).[9]

The theme(s) of the work

Novel as a Travel Guide

Being that this story was published in China Traveler and that in 1935 few Chinese people had ever travelled by train, Shanghai Express allows the reader to experience this mode of transport without actually hopping onboard. Zhang coveys this theme through the numerous aspects of train-travel described, such as the code of conduct in train cars of separating men and women in sleeping berths (4) or the various employees and amenities available like describing the peddlers selling beef jerky (31) or the porter who “[helps] passengers on and off the train” and “[makes] sure no pickpockets sneak aboard” (202).[9] By describing the rhythm of the train and the physical setting of the sleeping berths, Zhang plays on the readers' senses to transport them inside the train. Perhaps the most obvious indication of this theme is the descriptions of various cities and their attributes. The reader learns that Yangliutsing is characterized by its beautiful girls, or Pookow by its ferry and its saltwater duck (4-5).[11] The frequent train stops characterize the regional variations of China’s coastline and hence the novel allows the reader to vicariously experience train-travel by reading the book.[8]

Locomotive Time and Space of Modern Transportation

Shanghai Express provides a “revelatory footnote to the tension between tradition and modernization in all its pitfalls” (685).[10] In the novel, the train is utilized as a symbol for modernity. Zhang Henshui emphasized the novelty of punctuality in modern transportation. This is portrayed through stressing the concept of time of the train’s departures, “nowadays, when it comes to steamboats or trains, you’re dealing with large numbers of people, and they’re not going to be held up for just one or two passengers” (189).[9] On one hand, this accentuates the meaning of time by highlighting its temporariness as a form of escapade and adventure. On the other hand, one is bound to be destroyed if one can not survive in this notorious “paradise.” In the case of Hu Ziyun, he transitions from a first class to a third class passenger after he falls for a professional con-artist who deceives him of his money (685).[10]

Furthermore, the train is a “metaphor––a microcosm of a fast-changing society” (685).[10] The carriages highlight socioeconomic distinction, but the writer also utilizes the environment to introduce Liu Xichun and Hu Ziyun. The formation of their relationship elucidates the train as a time and space for opportunism, modern fantasies, and temporary liaisons.

Social Inequality Reflected by Train Compartments

Throughout Shanghai Express, train compartments represent socioeconomic classes of society which divide characters based on the train class ticket they can afford. First class has enough room for the people to live comfortably. Hu Ziyun even stated that “a lone woman in first class might be there to trade her body for money,” demonstrating the social divide between the ones who can afford the luxuries of first class versus the desperation of others to get there (52).[12] The second class is more compact for passengers; the people are less sensible towards others. Of course, there are also people who have higher diathesis who look upon these people with distaste. The third class makes up for the majority of train fares, however, it offers no place to sleep soundly and its passengers are victim to the train's malfunctioning temperature regulation system. If you are to leave your seat, someone will take it immediately. There is trash, human waste, "chicken bones and the empty shells of watermelon seeds," on the floor (133).[12] The stark difference between third class and first class reflects the different lifestyles or comforts afforded to one based off of social class. Accordingly, the train classes act as a social commentary on the harsh reality of social inequality in China.

Influence

With “more than one hundred novels and novellas, hundreds of poems, and thousands of essays” written under Zhang Henshui’s belt, it should be no surprise that he has influenced and continues to influence literary and cultural circles.[13] Although his popularity “developed at a slower pace,” “academic interest” grew rapidly in the later second half of the twentieth century (4).[14] “In Qianshan, Anhui in October, 1988,” a conference was dedicated to Zhang Henshui and “participants from various places in China and overseas” were present (4).[14] From his works, “it is clear that [he] was a keen, patriotic observer of social and political events in China’s wartime capital [and] was outraged by the moral and economic abuses that he witnessed”.[15] Not only was he “a patriotic writer who expressed serious concerns over social reality,” but he is also known as “an important transitional and crossover author between the May Fourth and Saturday Schools, the new and the old, and the Chinese and the Westernized during the first half of the twentieth century”.[15] Zhang is acknowledged for being able to “preserve the best aspects of the [traditional], while producing some writing that is every bit as “challenging” and “disturbing,” and thus “modern”” (114).[16] One of his “greatest achievements” was while “popular novelists” during his time were “in the business of producing “fiction for comfort,” (114)[16] Zhang took a different approach and “banished “dreamlikeness”” by writing fiction that “challenges [how we] view the world” (189).[17] His literature on reform movements had a pronounced impact on the cultural circle and his writing was evidently “seen as one of the vehicles for realizing a better society and a stronger nation” during a time of chaos (23).[14] Zhang Henshui’s influence goes beyond the literary circle and is “perhaps even [able] to change lives” (189).[17]

Media Adaptations

In addition, Zhang Henshui also had one of his literary works adapted into another art form. His novel 金粉世家/The Story of a Noble Family (Jin fen shi jia), written between 1935-1949, was adapted into a “commercially successful television” drama in 2002 and was “directed by Li Dawei and starring Chen Kun, Dong Jie, and Liu Yifei.”[15]

Further reading

On Mandarin Ducks and Butterfly Fiction:

For the Love of Her Feet by He Haiming[18]

The Lone Swan by Su Manshu[19]

Fate in Tears and Laughter by Zhang Henshui[20]

On Zhang Henshui

Innovation and Convention in Zhang Henshui's Novels[14]

"Zhang Henshui" in Chinese Fiction Writers[15]

Change and Continuity in the Fiction of Zhang Henshui (1895-1967): from Oneiric Romanticism to Nightmare Realism[16]

The World of Twentieth‐Century Chinese Popular Fiction[21]

References

- ↑ Bauer, Daniel J. "Book Review". Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- ↑ Yao, Jiaqi. "Zhang Henshui and China Traveler" University of British Columbia ASIA 351, February 8 2021 https://canvas.ubc.ca/courses/57921/pages/2-slash-8-asynchronous-lecture?module_item_id=2912947. Accessed 21 March, 2021.

- ↑ Bauer, Daniel J. "Book Review". Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- ↑ Wang, Yiyan. "Venturing Into Shanghai: The "Flâneur" in Two of Shi Zhecun's Short Stories". Modern Chinese Literature and Culture. Vol. 19, No. 2 (FALL, 2007): pp. 34-70 – via https://www.jstor.org/stable/41490981.CS1 maint: extra text (link)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Wang, Yiyan (2007). "Venturing Into Shanghai: The "Flâneur" in Two of Shi Zhecun's Short Stories". Modern Chinese Literature and Culture. 19: 40–41 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Heroldova, Helena (2000). "Shanghai Express (Ping Hu tongche) (review)". China Review International. 7: 278 – via Project MUSE.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 McClellan, Thomas (1992). "Zhang Henshui's fiction: attempts to reform the traditional Chinese novel". Literatures, Languages, and Cultures PhD thesis collection: 2, 71 – via Edinburgh Research Archive.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Heroldová, Helena (Spring 2000). "Shanghai Express: A Thirties Novel 平滬通車 (Ping Hu tongche)". JSTOR. 7, No. 1: 278–280 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 9.12 Zhang, Henshui (1997) [1935]. Shanghai Express. Translated by Lyell, William A. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press. pp. 1–259. ISBN 082481830X.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Chen, Jianguo (1998). "Review: Shanghai Express". World Literature Today. 72: 685 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Yao, Jiaqi. "Locomotive Time," University of British Columbia ASIA 351, February 10 2021 https://canvas.ubc.ca/courses/57921/files/12928738?module_item_id=2921197. Accessed 19 March, 2021.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Zhang, Henshui (1997) [1935]. Shanghai Express. Translated by Lyell, William A. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press. pp. 1–259. ISBN 082481830X.

- ↑ "Zhang Henshui". Gale Literature Resource Center. 2002. Retrieved 19 Mar. 2021. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Tam, King-fai (1990). "Innovation and Convention in Zhang Henshui's Novels". ProQuest. Retrieved 19 Mar. 2021. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 McClellan, T.M. (2007). "Zhang Henshui". Gale Literature Resource Center. Retrieved 19 Mar. 2021. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 McClellan, T.M. (1998). "Change and Continuity in the Fiction of Zhang Henshui (1895-1967): from Oneiric Romanticism to Nightmare Realism". Modern Chinese Literature. 10: 113–133 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 McClellan, T.M. (1992). "Zhang Henshui's Fiction: Attempts to Reform the Traditional Chinese Novel". Era. Retrieved 19 Mar. 2021. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Wong, Timothy (2003). Stories for Saturday: Twentieth-Century Chinese Popular Fiction. Honolulu, Hawaii: University of Hawai'i Press. pp. 61–72.

- ↑ Su, Manshu (1934). The Lone Swan. Beijing, China: Commercial Press.

- ↑ Zhang, Henshui (1930). Fate in Tears and Laughter. China: Chunfeng Art and Literature Press. ISBN 7531354225.

- ↑ Yi, Zheng (2015). The World of Twentieth‐Century Chinese Popular Fiction. United States: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp. 244–258. ISBN 9781118451588.