Course:ASIA319/2022/"Terrifying" (雷)

Introduction

The Chinese character '雷' ("léi") can either refer to the internet slang term that is used among the younger generations, or Chinese folk culture among the older generations. 雷 is used as a slang for someone being surprised or shocked by an experience, text, or visual medium; to the extent where they feels uncomfortable, as if "being struck by lighting".[1] An English equivalent to this slang is similar to the phrase "oh my God!", or being "lost for words".[2][3] 雷 can also be used for a situation where someone sees something and instantly likes it, similar to the term "一萌必中" (yī méng bìzhōng), roughly translating to "every cuteness will hit".[4] As a slang term, 雷 represents the young person's worldview, such as their attitude and want for freedom and recognition of innovation and creativity. Originally being used to refer to the natural phenomenon, thunder, 雷 has a variety of uses within the fan fiction and anime subcultures.

Etymology

Original meaning

雷 as a character has historically meant "thunder". On top of meaning "thunder", the character has been recorded as being used as a personal name as far back as approximately 1200 BC, as recorded on the oracle bone inscriptions of Shang dynasty China.[5] The character's shape is derived from the shape of the wheel, as the sound of the movement of the wheel resembled the sound of the rumble of thunder.[6] Early renditions of the character in the form of the oracle bone script (late Shang dynasty, 1600-1045 BC) resembled one to four wheels merged into a single character.[5] During the Qin dynasty (221-206 BC), the character, in the form of the small seal script, was rendered as "靁".[5] Chinese bronzeware referred to as "thunder patterns", 雷紋, or "cloud and thunder patterns", 雲雷紋, depicted Chinese perceptions on the shape of thunder in the form of convoluted lines which resembled early depictions of the 雷 character.[5]

The modern rendition of the character is a combination of two radicals stacked atop one another. The first is 雨, "Yǔ", which means rain. The second is 田, "Tián", which means field.[5] Thunder's connection with rain is straightforward, as the phenomenon of thunder is often associated with rain-bringing storms, while the second character, "田" originally began as a rendition of the archaic wheel pictogram, which was then converted to a modern context.[6] The character has been written historically as 𩇓, 𤴐, 𩂩, 𤳳, 䨓, 𩄣, 靁, 㗊, or 𤴑.[7]

Words that contain the character “雷” include 魚雷, hî-luî, "fish thunder", which means "torpedo".[8] Another word that incorporates “雷” would be tē-luî, 地雷, "ground thunder", which means "landmine".[8][9] Both meanings attest to the loud sound of thunder, comparing the sound that torpedoes and landmines emanate as reminiscent of the boom of thunder. Another word that uses “雷” is "léi dá", 雷达, which is a direct transliteration of "radar". It directly translates to "attain thunder", but the combination of the two characters are roughly analogous homophones to the English word "radar" and thus the word was created.[9]

Due to the usage of Chinese Hanzi in a variety of languages outside of China and within China, the character is pronounced differently depending on the region. In Mandarin Chinese the word is pronounced "Luî".[8] In Japanese it is pronounced four different ways. In the Kun'yomi reading, it is pronounced "Kaminari", "Ikazuchi", or "Ikaduchi". In the On'yomi reading, it is prounounced "Rai".[10] The word is derived from a combination of Japanese kami (god) and naru (to resound), to create the implied meaning of the "resoundings of gods".[11] In the the various dialects and languages in Japan the word is pronounced "kannai" in the Okinawan language, "kannare" in Kagoshima's Satsugu dialect, "kaminare" in Nagasaki's dialect, "narakamisan" in Saga's dialect, "kannaa" in Shimane's dialect, "okannarisan" in Yamanashi, and "narigamisama" in Aomori.[11] In Korean, it is pronounced "noe" or "roe", with the Yale Romanization rendering it as "loy" or "noy".[7] In Vietnamese it is pronounced "lôi".[7]

Colloquial meaning

According to the net dictionary Baidu Baike, the character 雷 has gained an online meaning of "extremely surprising", "startled", "shocked". There is an emphasis on the extreme level of surprise that is carried with the character.[12] The sensation of being struck by thunder was connoted with feelings of shock, a feeling of speechlessness, helplessness, or the sensation of your body turning cold from shock.[12] An alternative meaning, as proposed by Idongde, connects the term to the Chinese stock market.[13] In that context, a colloquial term is 踩雷, "stepping on thunder", which connotes making a risky venture by such as investing in a upstart company.[13] The term metaphorically compared the entering of a risky venture with stepping in a minefield, of which the Chinese word contained the letter for thunder.[13] Eventually, the meaning evolved past its use in the stock market, and symbolized risky online ventures such as purchasing a new color of lipstick.[13]

Allegedly, the phrase originated from net circles in the Chinese provinces of Jiangsu or Zhejiang.[12] Local dialects render a different word, to faint, as "Lei dao". The word was then possibly derived from the method of the Chinese keyboard's setup, when individuals who wished to type "faint" wound up having the character for "thunder" come up first, as both are homophones for each other.[12] Eventually, the neologism gained newer meaning as a way to express shock or surprise.[12]

Words Associated with 雷[14]

Basic Usage

- 雷电 (léi diàn); 雷雨 (léi yǔ) — noun

The explicit dictionary meaning of 雷 centers on “thunder” as a natural phenomenon. 雷电 refers to a thunderbolt, and 雷雨 to a thunderstorm.

- 地雷 (dì léi); 鱼雷 (yú léi); 雷管 (léi guǎn) — noun

As the world enters the era of hot weapons, 雷 is also used to describe bombs, explosives, or their components. 地雷 is the official term for landmines, 鱼雷 for torpedoes, and 雷管 for detonators.

Usage in contemporary slangs

- 雷 (léi) — noun/adjective/verb

雷 on its own can be a noun, adjective, or verb, signifying or describing the item or event itself that appears surprising and upsetting, or the action that inflicts such strong emotions on others.

- 雷到 (léi dào) — verb

Allegedly originating from dialects of Jiangsu and Zhejiang areas, the pronunciation of “lei dao” initially describes action similar to “collapsing” and “flipping over,” and gradually extended encompass the state of amazement, astonishment, and disbelief upon hearing or witnessing striking events. As this widened usage goes viral on online spaces, being “雷到” now represents being stunned in general, featuring a striking discomfort, as if being struck by a thunderbolt.

- 踩雷 (cái léi) — verb

Deriving from the contemporary slang above and 雷’s basic usage as explosives, 踩雷, literally meaning “stepping on a landmine,” now widely refers to encountering an unexpected and unpleasant situation, whether in trying out a new restaurant or reading fictions. This usage as a description of something exceptionally startling remains a highly popular expression, with multiple variations emphasizing on theatrical exaggerations, such as 天雷滚滚 (tiān léi gǔn gǔn), which literally refers to waves of deafening thunderclaps from the sky, now characterizes something being utterly striking to a horrifying extent.

- 雷人 (léi rén) — adjective

雷人, literally meaning “to strike a person with thunder,” is an adjective that is now used as “shocking.” Deriving from a 2018 news that reports the story of a man being struck by thunder after he had sweared to be punished by thunder if he was telling a lie, 雷人 has since been employed in an exaggerated manner to describe one’s sentiment of being shocked in the face of a person, an item, or an incident[15].

雷 in Contemporary Asian Popular Culture

Fan Fiction

The negative connotation of 雷 can amplify in its application to the field of fan fiction. Elements of a piece of fanwork that incites rejection, sometimes resentment, from a proportion of readers may vary, but oftentimes centers on the stacking of empty rhetorics, unrealistic storylines, characters considered OOC (Out of Character, the depiction of an established character breaks out of their trait of the original work), and tropes appearing acutely upsetting for certain audiences. Common examples in the final category include incest, genderbending, blasphemy, infidelity, male pregnancy, sexual slavery, prostitution, intersex, non-con, and character death.

Corresponding to Chinese netizens and fanfiction readers’ need to vent their discomfort upon reading pieces considered 雷, social media accounts dedicated to receiving and anonymously posting direct messages ranting about such fanfictions emerged, with the most prominent one of them, known as “雷文吐槽中心” (Ridiculous Articles Ranting Center) on Sina Weibo, followed by more than 980 thousand users at the time of writing.

When this proportion of provoked readers belongs to an online subculture with strong cohesion, 雷 can result in serious consequences. On February 24, 2019, the publication of a fanfiction titled Fall (《下坠》 xià zhuì) on Archive of Our Own, an internationally-based online archive of transformative works, which portrayed Xiao Zhan, one of the protagonists of this fiction and a real-life A-list idol in the Chinese entertainment industry, to be suffering from gender identity disorder. Featuring a controversial subject, this piece of fiction soon incurred backlash of radical fans of Xiao, who contended that Fall and AO3, as the fiction’s carrier, are guilty of spreading stigma, rumor, and sexual content of a public figure, and subsequently engaged in mass reporting of the platform to Chinese government agencies[16].

Being accused of its graphic depiction of what fans deemed to be “inappropriate content,” Fall has become a typical 雷 for this group of readers and has therefore given rise to remarkable consequences on a societal level. On February 27, three days after the article’s release, AO3 was officially blocked by the Great Firewall of China, rendering it inaccessible for Chinese users through legal avenues[17]. Meanwhile, multiple other platforms, including Weibo (Chinese counterpart of Twitter), Lofter (Chinese fanfiction archive), Douban (豆瓣), and Bilibili, were subject to a wave of strict state censoring on LGBTQ+ content[18].

Reviews and Recommendations on Online Platforms

雷 is also widely employed in the domain of online reviews, especially in a situation in which a consumer considers a good or service excessively unsatisfactory and attempts to warn potential consumers of their negative experience. Two words associated with 雷, “踩雷” (cái léi, “to encounter a ‘thunder’”) and 避雷 (bì léi, “to avoid the ‘thunder’”) enjoy the most popularity. A search of the two terms on Weibo (微博, the Chinese equivalent of Twitter), Bilibili (the Chinese equivalent of YouTube), and Xiao Hongshu (小红书) yield abundant results of consumer evaluations on various goods and services, encompassing video or text posts that comment on cosmetics, restaurants, clothing, and online shopping experience.

Comparing an unpleasant item or experience to “thunder,” commenters on online communities attach strong emotions to their assessment, a tendency that is also observed in their methods of expression, in terms of either physical gestures in a video or articulation in a text post. For example, a typical “避雷” post on Xiao Hongshu tends to feature eye-catching emojis, such as red crosses and warning signs, and sensational wording, such as “annual list of futile items that are not worth keeping even for free.”

Sensational Clickbait Titles

In the 2009 article written by Chang Chiung-Fang and translated by Geof Aberhat, the word 雷 was used as a clickbait title.[19] The article reviews how the internet plays an important role in the popularization of words to create new terms via online discussion forums. As well, these online slang terms could either have a good or bad meaning connected to them, depending on the context that it was used in. The internet and media has played a huge part in creating language for the younger generations, and can connect them with other people in the same generation. Similarly, a 2016 article written by Robert L. Moore about Chinese slang reviews how the importance of humor and playfulness in slang can promote social connection.[2]

雷 in Japan: Anime and Reaction to the News

This slang term first appeared in Japan in 2008, to describe the deep emotional reaction of anime character. These anime characters were thought to be struck by electricity, by whatever plot related-event, and then experience waves of shock. The term then transitioned to more common use; being used whenever fans of the anime would see something that surprises them, they would be shocked by electricity.[1] Some examples of where 雷 was used by netizens is the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, where over 69,000 people were killed and 18,000 were reported missing, or the series of snow storms that severely affected the south of China in 2008.[20] To describe their feelings or mood about these events, some could say that they felt that they were "struck by lightning".

Visual Internet Humor: Memes

The usage of 雷 has become more and more apparent in online culture ever since 2008, resulting in memes related to the slang or similar words, or even varying degrees to how impactful the lightning was. According to a 2013 thesis written by Alexandra Valery Draggeim from the Ohio State University about Internet Slang and China's Social Culture, the search results of memes relating to 雷 were around 38 million, while other words such as 雷人 and 雷事 had around 8 million and 1 million search results respectively.[21] Ever since the usage of 雷 became popular, netizens would combine words with 雷 and formed new words and new memes. In the thesis, it was stated that netizens could show their individuality by copying the word, and evaluate the matter from a personal point of view, and then express how the word would leave a big impression on themselves.

Surname

雷 is common surname in China, ranking number 80 out of 100 in the 2019 National Names Report conducted by the Household Administration Research Center of the Ministry of Public Security.[22] The surname can be written as "Loi", which is common in Macau, or "Lui" and "Louie" which are common in Hong Kong.[23] The surnames Lei and Lui are one of the most common surnames in Canada, ranking among the top 200, as determined by a study of health-card recipients in Ontario.[24]

Slang within Society

In an interview with Shen Xiaolong, a professor of Theoretical Linguistics in the Chinese Department of Fudan University, and a reporter from Jiefang Daily on November 17th, 2008, Shen Xiaolong stated that the slang term is not only popular, but it "also is a certain way of thinking and behavior of this generation of young people about life".[21] Shen Xiaolong explains how language is both a communication tool, as well as a cultural identity. The younger generations use new vocabulary that are different from older generations as a way to make a mark and show their existence, and so that the word 雷 is an example of an "identity mark" for these young generations.[21]

With Chinese culture emphasizing the idea of the "unification of thought", younger generations used the slang words such as 雷 to express their identity mark and their unique personality. In these younger generations, 雷 could reflect on both the cultural and social psychology of them.[21]

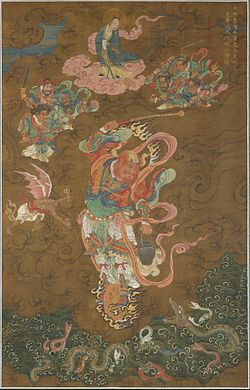

For the older generations, 雷 would be associated with the Thunder God, 雷公 (léi gōng), as well as the Leizhou Peninsula and people who lived there during the Sui and Tang Dynasties. At the time, there were multiple lightning and thunderstorms in the environment, and the indigenous people created their own culture, customs and bronze drums to compete with the storms. As well, the indigenous people created the image of Lei Gong, who they worshipped. This culture then grew after the Tang and Song Dynasties, once the Han people gradually immigrated to the Leizhou Peninsula. Grand temples for Lei Gong were built, such as the Lei Zu Temple that was built in the Tang Dynasty. For the opening ceremonies, thunder drums, carts, and fires were created, and activities such as singing, acting and martial arts were performed. This culture of the Leizhou Peninsula holds a great significance historically, geographically, and regionally. In modern times, this culture is still active and has become a festival in Leizhou, with the performances attracting thousands of tourists.[1]

In other words, the perception and use of slang within society draws clear divisions between members of said society:

- between old and young generational cohorts

- 'ingroup' versus 'outgroups'

Generational

Robert L. Moore defines basic slang in his 2004 article as an "expression that emerges when a young generation or cohort takes on a set of values starkly opposed to the values of its elders and begins to use a positive slang expression that is semantically linked to its new value orientation[2]." Under this definition, slang is a colloquial mechanism by which two distinct age demographics, the young versus the old, conflict. In 2009, the Taiwanese public had mixed reactions when gamer jargon was brought to the mainstream through a television commercial advertising the game “Sha Online[19]” The slang word in question, among others such as 雷 "thunder," was; "sha hen da." Literally translating to “kill very big,” referring to a brutal or sever kill- similar to the English gamer term ‘owned/pwned[25].’ Most of those who were outraged consisted of older-middle aged adults, who pointed to the terms lack of grammatical correctness. This sentiment is echo by English-speaking adults who claim that “our children don't know how to use proper English"[26]. Alternatively, poet Chen Li praised slang as an example of creativity in today’s youth[19]. Those adults who do incorporate slang into their every-day vernacular are often attempting to signal that they are “down with the kids.” Therefore, slang not only draws a clear line between the two distinct cohorts, but can also be used to bridge the distance and promote a sense of understanding of each others differences.

In-group versus out-group

"Lei" as a slang term, in reference to a terrifying event or noun, is not too far removed from its original definition as thunder. This logical connection between root meaning and innovative new application if not always clear where slang is concerned, especially on digital portals. For example, there is no overt reason why the first poster on a online forum is known as "the sofa" to Chinese netizens[19]. It is only through exposer does one become acquainted with the jargon and develop required knowledge for deeper understanding. This phenomenon of only those already 'in-the-know' or apart of the community utilizing slang being able to decipher its true meaning is indicative of the sociological phenomenon known as 'in vs out groups[27].'

- Ingroups: while an 'ingroup' can refer to like objects grouped together, when used to characters a groups of people it connotates that members of the group share a common interest or belief. 'Ingroup' and 'subculture' are often used interchangeably in layman's terms.

- Outgroups: is understood in relation to the 'ingroup.' If the 'ingroup' is an example of a 'subculture' than the 'outgroup' represents the homogenous dominant culture.

Language is used as a sign of kinship between ingroup members, promoting social connection[2]. For those engaged in fan fiction, "lei" is not just a slang word denoting something shocking, it also represents a genre of stories which are shocking at best, and bewildering, jaw-dropping, disgusting, and even terrifying at worst. Anime viewers are also an example of an ingroup who have their own understanding and application of "lei." Using slang and ingroup specific language fosters solidarity amongst members while further isolates the ingroup from the outgroup regardless of intention[28]; this alienation fuels potential conflict between ingroup and outgroup, such as the friction between generational cohorts.

Conclusion

Future of 雷

"Lei" as a slang term is incredibly popular. In a ballot conducted in 2008, 雷 was placed second as one of China's top ten most used online slang.[19] The term's intuitive meaning, from the natural occurring thunder to a shocking experience, might account for its high search results and common usage. Regardless of why "lei" is not some obscure word coopted by subculture groups unbeknownst by the dominant society. Along with 雷's usage by anime viewers, fan fiction readers and meme creators, we see the slang appearing in news reports and reviews. Unlike the vast majority of slang terms that come and go with each new generation, "lei" shows signs of longevity.

Suggestions for Further Research

There is a lack of academic research exploring 雷. Suggested studies revolving around the application of the slang term include:

- meta-analysis of contemporary content deemed as 雷 to uncover potential existing trends

- longitudinal study to see if the types of content labeled as 雷 evolves over time

Other social-cultural research questions could include:

- is there a connection between 雷 deemed material and societal values? For example: if a fan fiction depicting a pregnant man is written under the 雷 tag, how are transgendered individuals treated within the same society?

- will the same 雷 device loss its shocking qualities with repeated exposure? For example: if a politician is consistently exposed to engage in 雷 behavior, will the public reaction differ based on the quantity of times they are exposed to the information? Will the public become increasing angry, accepting or ambivalent?

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "雷文化". Baidu. November 30, 2021. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Moore, Robert L. (February 2, 2016). "Chinese Slang". Rollins Scholarship Online. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ↑ "雷 [léi] & 雷人 [léi rén]". Haha China. July 19, 2013. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ↑ "何为"一萌必中"". Zhidao Baidu. July 31, 2010. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 ""雷"". 漢語多功能字庫 (Multi-function Chinese Character Database). Chinese University of Hong Kong. 2014. Retrieved March 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ 6.0 6.1 Stallard, Rob. "Chinese character léi 雷 thunder". Chinasage. Chinasage. Retrieved March 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Moosbach, Dirk. "雷". WordSense Dictionary. Retrieved March 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 "雷 luî". 臺灣閩南語常用詞辭典 [Dictionary of Frequently-Used Taiwan Minnan] (in 中文). Ministry of Education, Republic of China. 2011. Retrieved March 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ 9.0 9.1 Liu, Chamcen. "雷 - Chinese Character Detail Page". Written Chinese Dictionary. Retrieved March 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Ahlström, Kim; Ahlström, Miwa; Plummer, Andrew. "雷". Jisho.org. Retrieved March 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ 11.0 11.1 "JLect - かんない【雷】 : kannai". JLect Languages and dialects of Japan. Retrieved March 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 "雷 (网络用语)". Baidu Baike (Baidu Encyclopedia). Baidu Inc. Retrieved March 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 "网络用语踩雷是什么意思 - 生活常识 - 懂得". 懂得 (Idongde). Idongde. Retrieved March 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "附录:汉语词汇索引/雷". Wiktionary. Retrieved March, 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "雷人". Baidu Baike (Baidu Encyclopedia). Baidu Inc. Retrieved March 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Jiang, Sunny (March 10, 2020). "Xiao Zhan and AO3 Fans Clash, Sparking Social Media Firestorm". Retrieved March 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ @AO3_Status (February 29, 2020). "Unfortunately, the Archive of Our Own is currently inaccessible in China".

- ↑ Gao, Dan (March 7, 2020). "观察|肖战事件及二次元的"升维打击". The Paper. Retrieved March 2020. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 Chiung-fang, Chang (June 2009). "Speaking with Hot-blooded Thunder--Chinese Online Slang". Taiwan Panorama. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ↑ "伤亡汇总_四川汶川强烈地震_新闻中心_新浪网". SINA. June 8, 2008. Archived from the original on May 19, 2008. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Draggeim, Alexandra Valery (2013). "Internet Slang and China's Social Culture: A Case Study of Internet Users in Guiyang". OhioLINK. Retrieved March 19 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "透过《二〇一九年全国姓名报告》,看我国的姓名文化及其发展". Sohu. January 1, 2020. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ↑ Hanks, Patrick; Coates, Richard; McClure, Peter, eds. (2016). The Oxford Dictionary of Family Names in Britain and Ireland. Oxford University Press. p. 1614. ISBN 9780192527479.

- ↑ Shah, B. R.; Chiu, M.; Amin, S.; Ramani, M.; Sadry, S.; Tu, J. V. (2010). "Surname lists to identify South Asian and Chinese ethnicity from secondary data in Ontario, Canada: A validation study". BMC Medical Research Methodology. 10: 42. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-10-42. PMC 2877682. PMID 20470433.

- ↑ Stegner, Ben (Feb. 22, 2022). "45+ Common Video Gaming Terms, Words, and Lingo to Know". MUO. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Bramlett, Frank (2002). "Slang: Awful Spector of Sloth?". English Faculty Publications. 50.

- ↑ Conklin, Abby (Jan. 09, 2022). "Ingroups and Outgroups". Study.com. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Drake, G.F (1980). "The Social Role of Slang". Language: Social Psychological Perspectives.

| This resource was created by Course:ASIA319. |