Course:ASIA319/2022/"Sick" (恶)

This is only a suggested structure. It is very likely that you will need to modify this structure to fit your topic:

Introduction

Sick in Chinese character is written as 恶 [è] and its dictionary meaning can be used to describe a state of evil, fierce, and ugly, also representing acts of crime and sinful deeds [1]. The word in Chinese culture consists of several representations, its implicit meanings goes beyond the dictionary. Additionally, it is a polyphonic word and each different sound (è , wù, ě ,wū) [2] creates a completely different meaning of the word, representing its diverse usage and implications in Chinese literature. Although the majority of the definitions tend to reside as derogatory terms, it is interesting to note that with global modernization, the Chinese meanings have evolved to illustrate commendatory terms along with wide adoption within influential trends in the digital world. The 21st century ever-growing popularity of the term represents an internet-empowered mass-participation including social media, film streaming, and creative entertainment platforms. The word at the same time reflects both political and cultural opinions through its varied usages.

The Genesis of 恶

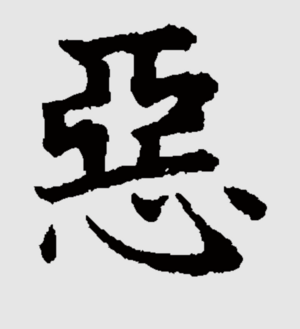

Chasing back to ancient Chinese history, it is difficult to trace the exact point of genesis but one of the earliest forms of 恶 [è] comes from Chinese scripted prose, and it is defined as evil and of fault [3]. In warring state periods, the word 恶 and its evil representations are also evident. The word’s basic composition consists of the Chinese character “心” at the bottom which means heart, illustrating that the evilness and sinfulness of one comes from the bottom of their heart and actions are influenced by soul. The top composition of the word consists of the Chinese character “亚”, according to the shape of ancient characters, one tend to think that the shape of “亚” look similar to the four corners of a tomb, implying that it has connectional meanings to tomb and death [4]. Most of the ancient royal tombs excavated by archaeological excavations are in the shape of “亚” and therefore it contains meanings implying death, funeral, and bad luck in general.

Because the word “恶” [è] has meanings of evilness and ugliness, if one dislikes something, such as the ugliness of something or someone, the different sound word “恶” [wù] can also be used here to describe “厌恶” [yàn wù], a detesting feeling towards something [5]. In the Eastern Han Dynasty, there was an imperial physician named Guo Yu. Guo was very skilled in the medicine area, and it was often easy for him to heal the people of the public. However, Guo found it difficult for him to successfully heal the royal nobles. When asked the question why, Guo explained that the royal nobles have adapted to indulging in leisure for a long time, pampering themselves and not necessarily trusting him, therefore the effects of medical treatments are not great. Guo described this state of the nobles using the Chinese idiom “好逸恶劳” [hào yì wù láo] [6], which describes the greed for comfort and resistant against labor, forming the origin of indulgence and dislike of labor.

Dictionary Meanings and Etymology of 恶

Dictionary Meanings

"恶" is a homograph character in the Chinese language that contains a few different meanings. Based on the dictionary, the word mostly contains two meanings. It can refer to the sensation of vomiting as well as the heinous behavior of people or things. Moreover, it can also mean to dislike or hate something or to commit a crime.

The character contains four different pronunciations, which are listed under[7]:

1. 恶 [è]

fierce and malicious

恶霸 [èbà] : villain who dominates by force

恶果[è guǒ]: serious consequences

恶劣 [èliè] : extremely horrible

Example phrases: 态度恶劣: horrible attitude

恶化 [èhuà]: change to the bad side;change of general reference relationship

Example sentences:

爷爷的癌症病情突然恶化了。Grandpa's cancer suddenly worsened.

癌症会引起全身性消耗及营养不良,会产生慢性的逐渐恶化的状况。Cancer will cause systemic consumption and malnutrition and will produce chronic and gradually deteriorating conditions.

2. 恶 [wù]

dislike or abominate; the opposite of “like”

厌恶 [yànwù] : to be disgusted based on products or people

Example sentences:

我最厌恶撒谎以及自私自利的人。I am disgusted with liars and selfish people.

3. 恶 [ě]

uncomfortable feelings, or refer to the aversion to people and things

恶心 [ě xin]: 1.feeling sick or in other word nauseating, want to vomit, called nausea in Medical Terminology

Example sentences: With the same meaning, it can be put in different places in the sentences.

伴随着一阵恶心,我来到了医院。With feelings of disgust, I went to the emergency hospital.

因为我产生了恶心的感觉,所以我选择来到医院治疗。I chose to come to the hospital for medical treatment because I had a feeling of nausea.

恶心 [ě xin]: 2.disgusting feeling based on horrible situations

Example sentence:

频繁出现的插队行为让人赶到恶心。Frequent queue jumping makes people sick.

4.恶[wū]

It is similar with “乌”[wū], which represents interrogative meanings; it can also express surprise.

恶: interjections in classical Chinese

Example sentence:

恶,是何言也!Evil, what words!

An identical word 恶心, for instance, can contain two different parts of speech as a noun and an adjective. The context can also convey different meanings to the reader. Depending on the dictionary, we observe the lengthy and in-depth evolution of the well-known Chinese languages.

Etymology

Etymology 1 :From Proto-Sino-Tibetan *ʔak (“bad”); cognate with Tibetan ཨག་པོ (ag po, “bad”) (Coblin, 1986; Schuessler, 2007). Also related to Thai ยาก (yâak, “difficult”) (Schuessler, 2007).

Etymology 2:Cognate with 安 (OC *qaːn, “where; how”), 焉 (OC *qan, “where; how”).

Etymology 3:For pronunciation and definitions of 惡 – see 噁. (This character, 惡, is a variant traditional form of 噁.)

Glyph Origin

恶 in Chinese Popular Culture: Multiple Meanings and Applications

恶心 Sick

The word "恶" has been passed down from ancient times and means "sick." The term "sick," or in Chinese "恶心" can be represented in two ways, depending on whether the feelings are physical or psychological. Nausea (恶心) is generally deleterious, and it is an unpleasant sensation that causes epigastric pain and the desire to vomit, and the feelings are transmitted to the body. Infectious diseases of the digestive system(消化系统感染性疾病), motion sickness (晕动症) and so on can all cause nausea. Nausea is probably a signal of a more severe and harmful disease. The underlying condition for more grievous conditions such as concussions (脑震荡) and brain tumors (脑肿瘤)is nausea or vomiting[8].

“恶心” can also refer to the aversion to people and things. People use “恶心” to describe foods which show gross tastes or gross looks. Psychologically, “恶心” is often interpreted as an aversive reaction to seeing decaying or toxic food (Carolyn, Wang Zuzhe 2003)[9]. For instance, the third-largest city in Sweden, Malmo, will debut the first "most horrible" food museum in the world on October 31, 2018. In the exhibition hall, there are many foods with local characteristics that are not recognized or liked by people globally, which contain cultural variation. Because of the cultural conflict, many foreigners cannot stand the taste of preserved eggs (皮蛋) and spicy rabbit heads (麻辣兔头) and describe them as disgusting; however, these two dishes are loved by many Chinese people[10]. In a similar vein, durian is a contentious fruit that people either love or hate. Some people consider it to be a global delicacy, while others insist that it tastes like shit. On the other hand, “恶心” is also been commonly used to describe annoying people. According to millions of research studies, most people believe that people with poor living habits and poor ideological qualities will be called disgusting. Such uncivilized habits as spitting and littering, as well as lying and other bad qualities, would all reflect the majority of people's descriptions of you as "恶心[11]".

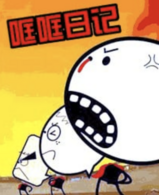

恶趣味 Evil Fun

The term "恶趣味evil fun" originally referred to those bad hobbies and strange alternative interests, but now the word "恶趣味" has been extended and has been given a new meaning. Some people with dark personalities also use 恶趣味 when calling themselves unique fun. The "evil" fun in the net anime) mainly refers to the cartoons produced by the network platform, which are typical in China, such as "100,000 cold 十万个冷笑话", "哐哐日记 Clunk Diary," "暴走漫画 Baozou Animation," "Brush soldier man's funny thearter 刷兵男的搞笑剧场" and "Corpse Brother 尸兄." The main point is that this kind of animation has the characteristics of "二次元," "nonsense," "parody," and "trolling," and the unique features are "cold jokes." The length of "evil" fun animation is mostly around 10 minutes, and it is broadcasted in seasons and updated in episodes. (Zhang Ying, 2016)[12] Evil" fun animation, with its unique "evil" characteristics, has become one of the most popular forms of animation and has a unique charm and appeal.

The first animation with the characteristic of "evil" fun was "South Park" in 1997, which has satire of American culture, the mockery of current affairs, a lot of black humor, and so on, which is liked by the audience. (Xia Chengnan, 2022) [13]After the development of "evil" taste animation in Japan, the first was the "funny manga Niwa 搞笑漫画日和" by Kosuke Masuda in 2000. Because of its parody, nonsensical plot, and famous then, Japanese appeared in 2011 "Full-time Hunter 全职猎人," "Super Genki Three Sisters 超元气三姐妹," "Human God Niwa 人神日和." With the development and popularity of the Internet, China is under the impact of the new "evil" fun animation from the United States and Japan, initially from the nostalgic evil fun animation "哐哐日记 Frame Diary" in 2009 to the explosive development of the manga-based adaptation of the 2012 "Baozou Animation 暴走漫画" and the 2013 "100,000 Cold Jokes 十万个冷笑话".(Bai Changxi & Ding Songhu, 2020)[14]

They are all loved by the public for their spiteful language, nonsensical plots, and parodic attitudes. In the "evil" fun animation film, the subversive plot makes the characters' personalities and characteristics in the story subvert the tradition. The innovation of action and production can show that the "evil" fun animation pursues entertainment first. However, in the animation film "ten cold十万个冷笑话," we can still see that there is something inherent in the spirit. Still, it also has a profound theme and connotation, mainly expressed in bravery, gratitude, justice, and cherishing time.

In the past, when people watched traditional animation, they would get certain truths or enlightenment from it, but the "evil" animation of the Internet has a large audience and brain-damaged fans today. So we can see the change in the concept and aesthetics of China's animation audience, which also reflects many social and cultural microcosms in China nowadays, such as otaku culture, fast food culture, subculture, etc. (Bai Changxi, 2019)[15]

While spoofing and adapting classics in a feckless manner, evil fun animation also refers to the edge of the current subculture. For example, homosexuality, which is not yet accepted by the general public in China, is mainly expressed in "Ten Cold 十万个冷笑话." (Liu Zhiqiang)[16]

恶搞 Kuso Culture

I. The origin of the Parody(Kuso) Culture

The word "Kuso 恶搞'' is a Japanese translation of the word meaning "shit, "'' abomination," or "bad." The Japanese word "Kuso'' was first popular in the 1980s when the Japanese video game industry was flooded with unplayable and buggy games used by gamers to express their discontent with these bad games. However, these bad and unbelievable games aroused the interest of some enthusiasts, and a group of experts who specialized in "bad games'' emerged. It even gradually formed a website dedicated to finding bugs. Some people started to make even worse parody versions of the same or similarly named games on emulators to satirize those bad games. "Kuso'' expresses a "serious game" attitude and promotes a spirit of "seriously facing bad things." The spirit of "Kuso'' gradually moved closer to local terms such as "weird" and "parody" as Japanese games were introduced to Taiwan. With the mentality of "nothing to laugh at, nothing to parody," the advocates spoofed and deconstructed anime and games to vent the pressure of work and study, "Kuso '' had more and more entertaining meaning. (Guo Juntao, 2008)[17] The object of Kuso is no longer limited to the original ACG field - anime, manga, and games. Everything can become the object of Kuso. Kuso has also been introduced in Taiwan and Hong Kong through various channels, especially the Internet. The rich information resources and unlimited Internet openness in the mainland have provided the soil for the survival and development of parody. Finally, Hu Ge's "The Bloodbath Caused by a Steamed Bun" made the term "Kuso" thoroughly popular, thus opening a new era of so-called parody. Kuso is not a simple concept; it represents a complex cultural phenomenon. In addition to online literary parody or online text parodies , there are online picture and animation parodies, online audio and video parodies, and online reality and current affairs parodies.(Lin Chen, 2008)[18]

II. Characteristics of Parody(Kuso)Culture

"Kuso" has some distinctive standard features: the unity of the natural world and the non-real world in opposition to each other, reflecting a carnival style of survival. Entertainment is the fundamental discursive attribute of parody culture. At the same time, parody denies authority, subverts classics, cuts down depth, deconstructs the center, and eliminates distance. (Lin Chen,2008)[19]

(i) Grassroots

When the mainstream culture may deviate from the real life of the general public and lose its humanistic concern, the Internet, which is virtual, popular, and efficient, provides the "grassroots" who are at the edge of the discourse with the convenience of expression and the stage of revelry. Under the impetus of the network, the phenomenon of "parody for all" has emerged, and "network parody" has become a carnival. The reason why parody is favored by cultural consumers and has a deep mass base is that parody culture also hides the grassroots desire for expression and releases the passion for life with the wild and unrestrained qualities of entertainment. However, due to the strong grassroots consciousness, parody is often temporary, popular, and uncertain. It, therefore, tends to be fashionable and perverse, mocking and following the crowd and pursuing sensory stimulation. (Li Yi & Wang Tianhao, 2021)[20]

(2) Carnality and Deconstruction

However, the parody loses its direction and runs nakedly toward vulgarity and kitsch. (Jiang Yunyao, 2020)[21] Parody is a concrete entertainment expression of postmodernism's subversive thought, rebellious spirit, self-promotion, and carnivalesque consumption consciousness and is a ritual resistance to tradition, authority, elegance, classics, and elites. The objects of parody are authoritative discourses, classical works, boring sermons, authoritarian political rules, etc. Parody is an alternative discourse to manifest an individual's historical reality and cultural activism, to shake absolute authority and hierarchical superiority, to deconstruct the norms and order of ordinary life, to break through the siege of ideologies and symbolic objects of various domains, and to enable individuals to defend their positions without having to submit to dominant ideas. (Cai Qi, 2007)[22]

恶女 Evil Woman

With the rapid progression of the modern digital world, the term “恶女” [è nǚ] have gained wide popularity online, particularly in movie films and tv dramas to represent female villain characters and their distinct personalities. In recent years, since the revenge of the concubines in the celebrated Tv drama “Empresses in the palace” (甄嬛传) to the female school bullier in the highly rated movie “Better Days”(少年的你), such characters have gradually earned an appealing place in the hearts of the audience, demonstrating their attractiveness as “bad women” of the century. Such characters are also recognized globally, such as the the counter-killing of the wife in the American comedy-drama "Desperate Housewives" (绝望主妇) to the group of female villains portrayed in Korean drama “The Penthouse: War in Life” (顶楼).

The term 恶女 originated from Japan, especially in traditional Japanese film and television works, where female characters frequently appear calm and rational, dark in heart while bold in action, and committed to revenge, which makes them appear dangerous but at the same time also charming and attractive [23]. Famous Japanese author Keigo Higashino is a significant creator of such characters, the life of character KarasawaYukiho (唐泽雪穗) in his novel “Journey Under the Midnight Sun” (白夜行) perfectly interprets the life and growth of an evil female character (恶女) [24] Yukiho’s character perfectly illustrates the dark and fierce soul under an elegant and noble posture.

The female villain character is undoubtedly intimidating. But oftentimes, the more evil the flower, the more deadly temptation it exudes, influencing people to approach cautiously, to explore and discover her heart. In recent years, whether in movie films, television works or in real life, audiences tend to prefer more complex and realistic women characters that demonstrate human desires and audiences are more inclined to see creations of“bad women” characters (恶女人设) brought to the big screen, and the pursuit of its roots lies in profound social issues.

Evil and bad women characters and its ever growing popularity represents the challenge of individualism to collective authority after decades of suppressed attitude towards gender inequality. The ideology of “恶女” [è nǚ], therefore promotes the awakening of feminism and female independence [25].

恶-吐 / 彩虹 Puking / Rainbow

The term “恶吐” refers to “puking” or “puking rainbow” in English. In the modern age of rapid technology development, social media has become a popular platform of communication for Chinese society. This form of communication comes with many different emojis, and “恶吐” has been given a new meaning to express two specific emojis as reactions to messages or internet content.

“Puking rainbow” describes an emoji of usually a happy face, or any other cartoon character throwing up rainbow from their mouth. It is usually used as a positive emoji, as the character is often displayed with a happy expression or a smile. It originated (9) on a blog site where the owner visited a place called “小京东“, similar to Chinatown but in Japan. After overeating, he threw up a variety of colourful food including fish, tofu, and Japanese snacks. It’s appearance was extremely similar to a rainbow, and he covered up the puke with many different colours when posting, creating a meme that went viral over the internet. Social media users in the comments began to recreate his image as an emoji or gif, and it was reshared countlessly before becoming a popular trend that people used to react to each other online. Shortly after this trend began, the owner of the blog purchased the domain: RainbowPuke.com where he published all kinds of puking rainbow images, cartoons, and characters. Until 2009, the subject of this puking rainbow trend was talked about all over social media and after became a regular emoji that social media users used on a daily basis.

“Puking” (10) describes an emoji similar to “puking rainbow”, except it features a character throwing up green puke from their mouth. The character often appears as if it is struggling or feeling unwell, with their eyes closed and mouth opened in a circle. The origin of this emoji came from one of Apple’s IOS updates a few years ago, and after being introduced as an new emoji, became one of the most popular expressions Chinese social media users go to when expressing both physical and psychological sickness. A popular way that social media users use this emoji is as a reaction to bad news or content they disapprove of. They often reshare this emoji to show that they are uncomfortable or do not like this content. This emoji is also used as an insult to images of people where they don’t look their best, or negative reactions to their characteristics or “gossip” about them that one finds unappealing. Another popular way Chinese social media users use this emoji for is when expressing feeling disgust, unwell, or physically sick. As the emoji is associated with negative feelings, it can often represent real life scenarios where the individual is actually feeling unhealthy.

The term “恶吐” merely defines two forms of emojis on the internet, and is loved by all social media users who regularly uses them to express their feelings on public forums or in private conversations. They are extremely popular emojis that can be used to express a variety of feelings and enhances the thoughts they want to communicate with visual representation. Although the two comes from very different origins, their popularity can be attributed to the different ways they can be used and the humor they add to conversations. In the modern day, the emojis representing “恶吐” greatly strengthens the communication methods between social media users online.

Social, Cultural, and Political Implications

The Ecological Problems caused by 恶心

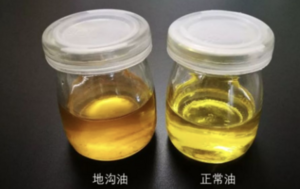

The term "恶心" could also refer to societal phenomena. The problem of food safety is not just a concern for meals, but also as significant as it concerns scientific development and social harmony and stability. The gutter oil (地沟油)incident made many people feel sick. Whenever people mention gutter oil, the adjectives used to be "disgusting" (恶心),"harmful business", and "unhealthy". In order to get more economic gain, some unscrupulous merchants chose gutter oil, which has great destructive power for the human body. The gutter oil incident has become world-spread, and it has also sparked debate in both Chinese and American mainstream media. (Jin Mei, Fang Zongxiang, Hong Ying, 2018)[26] The issue has progressed beyond just being a food issue and now involves politics as well.

Twelve nature news articles claim that China Daily and the New York Times report on gutter oil in exactly opposite ways, with China Daily frequently emphasizing a healthy China, the government's efficient handling of the situation, and proper treatment of the gutter oil incident. The two newspapers show significant differences in their reporting positions where in different perspective. This leads to a globally political institution for which many western countries have a premise that is based on their past thoughts or experiences. Some news reporters subconsciously held hostility and prejudice against China, and these news content would try to cater to the public's preferences. As a result, the gutter oil crisis has become a cross-cultural problem that should garner the attention of domestic government departments and media departments. Our media could take the initiative in today's global information culture and promptly address the concerns and inquiries of the western media. Some news reporters subconsciously held hostility and prejudice against China, and these news content would try to cater to the public's preferences. (Jin Mei, Fang Zongxiang, Hong Ying, 2018)

On the other hand, gutter oil has another possibility of turning waste into treasure. In Douala, the largest city in Cameroon, the waste oil discharged from many restaurants and large hotels becomes an environmentally hazardous trench oil. To change this situation, Bellomar, a company specialized in sanitary goods production, began a survey of the local trench oil status and attempted to develop innovative trench oil treatment methods. Finally, they discover that as a fat and oil with lubricating and saponifying properties, it is never better to be used to make detergent![27]

As a result, the gutter oil crisis has become a cross-cultural problem that should garner the attention of domestic government departments and media departments. Our media could take the initiative in today's global information culture and promptly address the concerns and inquiries of the western media (Jin Mei, Fang Zongxiang, Hong Ying, 2018) Oppositely, After being transformed, any disgusting and appalling event could be turned into a positive situation, which is better for our society's development.

The Disappearance and Prosperity of the 恶搞 Culture in the Contemporary Society

The emergence of Internet spoofing has a complex and profound social background. It is an outburst of the collective emotions of the society in transition after a long period of latency, a collective rebellion against the national character that has been accumulated for thousands of years, and a small-scale challenge to traditional moral concepts. (Liu Xueyu,2017)[28]

The first network parody has entertained the public. Even the critics of parody will agree that network parody is a good form of entertainment, which is direct and does not require the audience to interpret it seriously. Therefore, entertainment is the key to its vitality. (Xu Xinmiao, 2019)[29]

The second network parody has the social function of exposing, satirizing, and criticizing. For example, although "闪闪的红星-潘冬子 The Shining Red Star: Pan Dongzi" reverses the facts, confuses black and white, confused logic, and is suspected of destroying the image of Pan Dongzi, the little hero in the nation's mind, it exposes and criticizes the current popular talent show shady practices.

Although this questioning and the way it is done may be absurd, it at least provides another way of interpreting the world in which the sacred, the sublime, the solemn, and the authoritative are reduced to their stock status. For example, the "pseudo-encyclopedia 伪基百科 '', which "does not provide any standard answers", is a "politically incorrect, non-informative online encyclopedia". The relationship between Pseudopodia and Wikipedia is like a deformed twin of the dragon brother and mouse brother genre. Many geography-related entries in Pseudopodia are haphazardly labeled, described, or located. (Hu Jing, 2009)[30]

Internet parody has set off a grassroots revolution in mass media discourse, a milestone in the audience's struggle for equal communication rights. The grassroots are considered "both a community on the Internet and a large group of youth-centered people. They are not the so-called 'successful' nor the pure 'underclass,' but they have a clear sense of 'middle income' because they are still young and hopeful. But today, they are a unique force once they gather on the Internet, which has a huge influence. Both "grassroots culture" and "parody culture" originate from the public's desire for cultural discourse, which has existed since the birth of popular culture. Only the Internet has genuinely transferred cultural discourse to the public to satisfy this desire fully. (Wang Guangliang, 2016)[31]

Internet parody provides a "vent" for social tensions and pressures and is a "control valve" to relieve tensions and antagonisms. Network parody plays the role of a collective game and releases the antagonism between alleviated groups. For example, the Internet users' parody of "SuperGirl 超女" diverted the public's attention from the shady business of the talent show and gave some space for the survival and development of the talent show.

Internet parody itself also has commercial value. The most obvious example is the movie "Crazy Stone 疯狂的石头," which earned good box office revenues under the banner of parody. There is also the TV series "Wu Lin Wai Zhuan," which has also gained good ratings. Parody is also derived from books, music, movies and cartoon dolls, and other corresponding products network parody business value can not be underestimated. A few years ago, the explosion of the "Wan Wan Mei Xiang Dao 万万没想到'' and "Report Boss 报告老板”and other secondary creations of nonsensical parody videos in a period popular nationwide. (Xie Tingyu, 2021)[32]

It cannot be said that parody culture does not have any political influence, and some parody texts have touched a political nerve and made officials feel uncomfortable. Still, most parody authors and readers have yet to engage in further critical actions after symbolically overwhelming the hegemony and the system. The parody of Wuji 无极, for example, only symbolically defeats 陈凯歌 Chen Kaige's double domination of culture and capital. (Qian Yijiao, 2005) [33]Still, it cannot change the reality of Chen Kaige's power of these two rights, nor can it change the Hollywood-oriented blockbuster mechanism that has emerged in the Chinese film industry in recent years, which is obsessed with luxury, grand spectacle, and sensory stimulation. Contemporary Chinese parody culture adheres to certain qualities of postmodern consumer culture, deviating from mainstream cultural expectations and appearing in front of the world as deviant, joking, and playful.

On the one hand, it breaks the so-called decent life, subverts, and resists the discipline of the dominating force in an entertaining way. At the same time, outside of entertainment, spoof culture opens up the public discourse through the Internet, China's "public sphere." It has become a particular style of criticism representing the general public, highlighting the cultural tide that has long been obscured by mainstream ideological discourse.

But on the other hand, the popularity and proliferation of parodies also bring challenges to our social life, such as the aesthetic fatigue and degradation brought by the excessive generalization of entertainment and the challenge of the political, moral, and legal bottom line by the overblown parody. In addition, the parody dissolves the authority and hegemony simultaneously, relying on the powerful will of the coaxer behind it to turn into a tyranny of discourse, which is also why it is criticized and reproved. (Tang Shiren, 2020)[34]

Although parody culture is characterized by subversion and disintegration, the public can get a kind of resistance to the pleasure of risking and avoiding authority through parody. Still, this resistance is only ceremonial and cannot shake the dominating power. The pioneering nature of parody culture has been weakened and denied under both political and commercial suppression. Nevertheless, parody culture is still an important cultural phenomenon in Chinese popular culture in the context of globalization. Whether people like it or not, the massive field of meaning it provides is a fertile cultural ground worthy of continued exploration. (Zeng Yiguo, 2012)[35]

Contemporary political parody is gradually disappearing as China's ideological and mainstream media discourse is strengthening progressively. We can only see content related to political parody and history parody published on mainland channels. At one time, on the Bilibili website, we could see clips parodying various political figures, from Wallace and Jiang Zemin 江泽民 talking and laughing with emoji packs to Stalin and Hitler's lalang(拉郎-fall in love) CP clips or Xi Xi Ha Ha 习习蛤蛤 and other harmonic parody statements. (Yang Man, 2017) [36]These political parodies were eventually short-lived on the mainland. But on foreign mainstream social media such as Twitter, these parody videos are mentioned and used as frequently as spoofs of Western political figures. So as far as "parodies" are concerned, only harmless jokes such as parody celebrities exist in mainland China. All parodies that "subvert" history and regimes no longer exist. Parody history is also not tolerated in China. The "BaoZou Animation 暴走动漫" was taken off the air and ordered to be corrected for the parody of "Huang Jiguang, the hero who blew up the bunker." Domestic ideology and Confucianism have always been against or banned from parody culture.

While there is no longer any ground for the growth of parody culture in China, the propaganda of the Western free spirit has revitalized Chinese political parody culture. Whenever a political or diplomatic event occurs between China and the U.S., people on Twitter create all kinds of political emojis, clips, and even songs to satirize the current diplomatic and political situation. Whether it's in the West or China or about Xi Jinping or Trump, parody politics is essentially a satire of power relations by the masses, a challenge to hegemony by grassroots people. Even in the West, full of free spirits, people's right to parody is only to parody, and all they can do is play the only space they have in language and cultural creation. Parody politics ultimately does not affect any ideological change and can even be used by political parties as a political tool and sacrifice.(Huang Xiaowu, 2003)[37]

In contemporary Chinese culture, the word "恶" has many applications not only in pejorative terms. For example, the traditional original meaning of the word is to sweep away evil, to be cynical and vicious. The words "恶", "恶女", and "恶搞" are not only deconstructed to have different meanings in the new context of the Internet, but also contribute to the spread of subculture. Nowadays, 恶搞 culture, 恶女culture and other "恶" culture are popular in Chinese mainstream media, reflecting the new rebellion and new thinking of contemporary youth.

Conclusion-The Cultural Transformation of 恶

To summarize, "恶" as a polyphonic character, it has numerous meanings beyond its basic pronunciation in Chinese literature. Since ancient times, it has been regarded as the word to express negative meanings. From how "恶" [è] has been linked to expressions of evil and of fault since history to how "恶" [ě] has been widely used to express physical and psychological unpleasant feelings such as vomiting rainbow emojis on the internet, we undoubtedly see not only progression, but the importance of influences within past and modern Chinese popular culture, expanding the endless possibilities in usages of the complex Chinese character, including its shifting of attitudes. In addition, the word simultaneously adopts and expresses political and cultural opinions through its conjunction usages with various terms under different circumstances . The gutter oil crisis is not only a repulsive social problem exclusive to China, but it also represents a larger global issue hidden within Western countries due to cross-culturally misleading information. The parody culture (恶搞文化) subverts the traditional ideology and education system but looks at this phenomenon from a new perspective. It provides an outlet for negative emotions and suppressed voices in society so that the public can relieve tension and restrained feelings through humorous and sarcastic content, with fewer risks of facing consequences from the state. Similarly, “evil female culture“ (恶女文化) is not only representing villain characteristics but also reveals decades of suppressed attitudes towards gender inequity and rights; its growing popularity signifies the challenge of individuals to communal authority, shifting the term from pejorative to complimentary approval. This shifting of attitude towards the comprehension of the term marks a significant turn in the power of Chinese literature, the impacts of Chinese popular culture, from a socialist perspective to accepting neoliberalism, under the influences of modern technology, incorporating cultural values of past, present and future possibilities.

References

| This resource was created by Course:ASIA319. |

- ↑ "Xinhua Dictionary". Retrieved Nov 13 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Yabla Dictionary". Retrieved Nov 13 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Han Dictionary". Retrieved Nov 13 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "HBTV.COM.CN". Retrieved Nov 13 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Gu Wen Guan Zhi Dictionary". Retrieved Nov 13 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Yuwen Website". Retrieved Nov 13 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Sick Definition".

- ↑ "Nausea Medical terminology".

- ↑ Wang, Zuzhe; Korsmeyer, Carolyn (2003 July). "Pleasure, Delicious, Nausea". Journal of Nanyang Normal University Social Science Edition. 2 (7): 20. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "World's most disgusting food exhibition". Zhihu. Oct. 10th 2018. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Are there people around you who are full of lies and hypocrisy? What do you think?".

- ↑ Research on "evil" Interest in Network animation Creation, Zhang Ying, 2016

- ↑ The Bad Taste of American Adult Animation, Xia Chengnan, 2022

- ↑ A study on the 恶趣味 culture of Chinese animation images, Bai Changxi & Ding Songhu, 2020

- ↑ A Study on the Media Interest of Chinese Animation Images - Taking Which Scold as an Example, Bai Changxi, 2019

- ↑ Ethical Considerations of "Internet Parody", Liu Zhiqiang

- ↑ An exploratory study on the dissemination of online parody videos in China, Guo Juntao, 2008

- ↑ A Cultural Interpretation of the "Parody" Phenomenon in Contemporary China, Lin Chen, 2008

- ↑ A Cultural Interpretation of the "Parody" Phenomenon in Contemporary China, Lin Chen, 2008

- ↑ "Analysis of the Phenomenon of "Internet Parody" and Reflections on Response", Liyi & Wang Tianhao, 2021

- ↑ A Study of Internet Parody Culture from the Perspective of Carnival Theory, Yunyao Jiang, 2020

- ↑ Reflections on the Culture of Internet Parody, Cai Qi, International Journalism, 2007.1

- ↑ "Zhihu: How To Understand The Evil Women In Japanese Culture". Retrieved Nov 13 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Jin, Tao. "A Study on the Image of Evil Girls in Keigo Higashino's Literary Works". Cnki. Retrieved Nov 13 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "What Can We Learn From The Evil Woman?". Pengpai. Retrieved Nov 13 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Mei, Jin; Fang, Zongxiang; Hong, Ying (Dec 2018). "A Comparative Study on the Reports of Trench Oil Incidents in the Mainstream Media of China and the United States -- Taking China Daily and New York Times as Examples". Philosophy and Humanities: p164-167.CS1 maint: extra text (link)

- ↑ "I changed! I am a dream gutter oil!". April 12th 2019. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Online Parody in the Age of Pan-Entertainment, Liu Xueyu, No. 3, 2017, Dongwu Academic

- ↑ Reflections on the media ethics of parody short videos from a subcultural perspective, Xu Xinmiao, 2019

- ↑ Interpretation of Youth Subculture Characteristics of Internet Parody Phenomenon, Hu Jing, 2009

- ↑ A study on the phenomenon of online parody from the perspective of carnival theory, Wang Guangliang, 2016

- ↑ The Bantering of the Rice Circle: Flirtation, Parody and Self-Empowerment of Fans, Xie Tingyu, 2021.11

- ↑ The movie "Wuji" is telling a myth [J], Qian Yijiao , Xinmin Weekly, 2005(12)

- ↑ The Aesthetic Ethics of Evil --- Understanding Evil in Modern Narratives, Tang Shiren, 2020

- ↑ New Media and the "Social Politics" of Contemporary Parody Culture, Yiguo Zeng, 2012

- ↑ The construction of subcultural style of online emoji: from self-expression to public space[J]. Journal of Xi'an Jiaotong University Social Science Edition, Yang Man, 2017 (5): 88-92.

- ↑ Culture and Resistance - A Study of Youth Subcultures in the Birmingham School, Foreign Literature, Huang Xiaowu, No. 2, 2003