Course:ASIA319/2022/"Rotten" (腐)

Introduction

The Chinese character, 腐 (Pinyin: Fǔ), is a popular slang term which directly translates to "rotten" or "decay." [1] More commonly, this term is used as slang in reference to Danmei (Chinese: 耽美, Pinyin: Dānměi) which is otherwise known as boy's love (BL) fiction, a genre of media which deals with the romantic or sexual relationships between two male characters. Danmei is encompassed in a wide variety of media forms, including manhua, novels, webtoons, fanfiction, and more recently, TV dramas, and donghua. Fǔ (腐) often appears in combination with other characters, such as "腐文化" (Pinyin: Fǔ wénhuà, English: "rotten" or "corrupt culture") and most commonly, the word, "腐女" (Pinyin: Fǔ nǚ, English: "rotten woman"). A fǔ nǚ is a girl or woman who actively consumes BL media and is a self-proclaimed fan of the BL or Danmei genre. [2] The BL genre originates from Japan but Chinese Danmei culture has become increasingly popular in China in recent years, especially amongst female readers and viewers. Due to social and cultural attitudes surrounding homosexuality and queerness, Chinese 腐 culture is sometimes stifled by society. However, the consumption of Danmei in the online sphere flourishes and the Internet provides a space for communities to form and connect through 腐 culture. As such, the vast popularization of BL and Danmei fiction in Chinese media and popular culture has transformed the original and ordinary meaning of the character, 腐 into a commonly used Internet slang term.

The Genesis of 腐

In addition to the traditional meaning in the dictionary, the word "腐" has become popular in recent years and has become popular in the public view with the word “腐女” (Pinyin: Fǔ nǚ, English: "rotten woman"). The word "腐女" is derived from “婦女子(ふじょし)” or fujoshi in Japanese. "腐" means "hopeless" in Japanese and it is used to describe girls who like to consume BL (boy's love) cartoons, manhua, and fiction. In Chinese context, the word "腐女" mainly adapted the meanings from Japanese culture. At the same time, the "腐男" (Pinyin: Fǔ nán, English: rotten boy) can also be used to describe the male groups who consume BL artworks.

Danmei and BL fiction arrived to China in the 1990's from Japan. In the late 1980's Japanese BL manga spread to Taiwan and then later spread to other Chinese-speaking regions like Mainland China and Hong Kong. Imported Japanese BL manga as well as translations of Western slash fiction (the Western equivalent of Danmei and BL) have since become a popular form of media for younger Chinese girls and women. [3][4] The word "腐" has become a slang term to describe the culture, communities, and practices of fǔ nǚ and individuals who enjoy reading or watching Danmei and BL content. The usage of the word, 腐, became more common with the growing usage of technology and the Internet in the 2000's, especially as Chinese 腐 culture and community is mostly confined to Internet spaces due to Chinese laws against pornography. Online Danmei and BL manhua websites such as Jinjiang Literature (created in 2003) and Xianqing are able to provide safe reading experiences for Chinese fǔ nǚ who want to consume BL fiction by ensuring anonymity. [5] These websites accumulate huge numbers and are a sign of the just how popular Danmei, BL fiction, and 腐 culture is amongst Chinese readership since the 2000s: Jinjiang Literature, receives over 2 million log-ins per day. [3]

Besides, with the introduction of the policy “反腐败” (Pinyin: Fǎn fǔbài, English: “anti-corruption”),the word “反腐” (Pinyin: Fǎnfǔ) has gradually become active in the public view. “反腐” refers to the fight against those who have high official positions but use their own positions to embezzle. The phenomenal anti-corruption TV series In the Name of the People launched in 2017 and has been highly praised by people.

Explicit Meanings of 腐

Dictionary Meaning of 腐

腐 can be used either as an adjective or a verb. The dictionary meaning of 腐 (Pinyin: Fǔ) is "rot; decay; spoil; rotten." [1] In it's original meaning, 腐 is seen in words such as 腐败 (Pinyin: fú bài, English: corrupt; corruption), 腐蚀 (Pinyin: fǔ shì, English: to corrupt; to deprave), or 腐朽 (Pinyin: fǔ xiǔ, English: rotten; decayed; decadent; degenerate). 腐 can also be used to describe old or outdated ways of thinking. [6]

Examples of 腐 Usage

- Rot; decay - 腐烂 (Pinyin: fǔlàn), 腐朽 (Pinyin: fǔxiǔ)

- Outmoded ideas - 迂腐 (Pinyin: yūfǔ)

- Bean products, for example - 豆腐 (Pinyin: Dòufu)

- In ancient times, it refers to palace punishment, for example - 腐刑 (Pinyin: Fǔ xíng)

- People who are keen on BL (boy’s love) culture - 腐女 (Pinyin: Fǔ nǚ), 腐男 (Pinyin: Fǔ nán)

Etymology of 腐

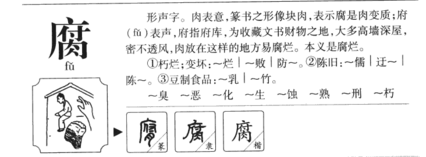

The formation of the character, 腐, is pictophonetic. The radical, 肉 (Pinyin: ròu, English: meat), is the semantic component which suggests the meaning of the character while 府 (Pinyin: fǔ, English: prefecture; prefect; government) is the phonetic component which suggests the pronunciation. [7]

腐's variegated new meanings, actual usages, and value-loaded implication

Beyond its dictionary meaning, 腐 has taken on a new meaning in Chinese pop culture. It is used as an adjective to describe all cultural creations (web novels, comics, dramas, etc.) about homosexual love and women (and in less cases, men) who enjoy consuming cultural products about homosexual love.

This new implicit use of "腐女(rotten women)" was initially reserved for online internet discussion forums discussing Japanese anime and idol groups, and was used to find co-lovers for online chatting and communication. For example, a post published in February 2006 in the Baidu Tieba forum of the Japanese idol group V6 was titled "腐女(rotten women) Chat Room - if you're not a fan of fu, don't click" and emphasized in the post that "腐 is a good thing, if you don't like it, don't come in and cause trouble for yourself!"[8]. In the early days of this emerging meaning of 腐, it was restricted to a small, subcultural community, and was mostly used as a self-reference for people who were fans of Boy's Love.

With the proliferation of web novels and TV episodes featuring Boy's Love, the new meaning of 腐 became known to the general public and began to appear in media articles. 腐 was applied to describe a specific kind of romance episode focusing on homosexual (usually male) love. In most cases, when the article is intended to introduce a 腐 drama outside of China, the two same-sex leads of the drama will explicitly identify their romantic relationship with each other. However, when the articles refers to Chinese 腐 TV series, even if the protagonists do not claim to love each other, these shows can still be categorized as 腐 dramas when there are many hints of a special relationship between the two male leads. For example, an opinion piece published in the traditional media Xinmin Weekly referred to the 2018 online drama Guardian as a Fu drama, even though the two male leads in the drama claim they are just "brothers".[9]

Associated words

Fǔ Nǚ(腐女)

This term refers to women who enjoy male-to-male romance-themed works. Fǔ nǚ can derive pleasure from imagining a romantic relationship between two males. The male pairings they are attracted to are not limited to characters in artworks, such as films, TV series, novels, web fiction, but can also be two male members of an idol group, two historical figures, etc. As a derivative of the term fǔ nǚ, Yuándān Nǚhái and Tóngrén Nǚ define the types of cultural products they consume.

(1)Yuándān Nǚhái(原耽女孩)

This term refers to girls who read and enjoy original Danmei stories. The male pairings they are fond of are characters from this specific fiction genre Danmei.

(2)Tóngrén Nǚ(同人女)

This term refers to girls read or create artworks based on secondary fan creations of two existing same-sex characters.

Bǎihé Zhái(百合宅)

This term is relative to fǔ nǚ, refers to men who enjoy female-to-female romance-themed works. It is not as widespread as fǔ nǚ in mainland China, yet in Taiwan, this term gained more in popularity. A comic book translated from Japanese manga was published in 2017 in Taiwan, entitled "I am fǔ nǚ, he is baihe zhai".

Fǔ Ài(腐癌)

This term means 腐 cancer, is often used to describe fǔ nǚ whose behaviour makes others feel unpleasant in social situations. Users of this term assume a moral code for the community of fǔ nǚ that must be followed, such as not promoting 腐 culture or pairing male historical figures. If a fǔ nǚ's statements about same-sex love cause discomfort to others, they would be condemned as fu ai.

Counterpart terms

In English, if a film or TV series is primarily about a love story between two men, the episode will be called a "Boy's Love Drama". This crosses over with the concept of 腐 drama, for example, the Thailand TV series I Told Sunset About You (2020), which is described as a "Boy's Love Drama" on the IMDb site, while in China it is referred as "Thai Fu(泰腐)". The term "bromance" means that the two males in the story show a tight, affectionate bond but do not enter into a romantic relationship. Fu contains both of the meaning of "Boy’s Love" and "bromance".

In Japanese, Fujoshi is the orginal word of 腐. Fujoshi can be defined as "women who enjoy novels and manga dealing with male-male romance, which are mainly created by women." [10] However, 腐 in the Chinese context has been to some extent detached from the bondage with the female group and can be adopted for all matters related to same-sex love.

Meanings in context

When 腐 is used to describe artistic productions, such as 腐 drama or 腐 fiction, it contains a functional reference, stating that these productions are based on the theme of male bonding. When 腐 is used by consumers of 腐 culture, the broadness of meaning contained in this word can help them search for, exchange, and promote more consumptions of fu culture. In an article written in 2020 and posted on the Douban forum, the author recommended 60 腐 dramas from all over the world to readers. She included Chinese drama adaptations of Danmei fictions, Japanese and Thai TV series that portray male love directly, and Korean male-female romance dramas that include hints of male-male relationships.[11]

Newspapers and magazines will also use the word 腐 to describe the recent popularity of some Chinese TV dramas. Since mainland China's laws do not allow same-sex marriage, in TV dramas, same-sex love cannot be shown directly, but can only be implied. For the media, it is neither inaccurate to use the term “homosexual theme” to describe a drama series, nor “safe” to point out the same-love elements. 腐, on the one hand, is a word of Japanese origin, and is not a direct statement of homosexual love. On the other hand, it serves to identify non-romantic male relationships. The playful meaning of the imported word 腐 allows the media to avoid touching on sensitive and potentially censored issues of gender and sexual orientation, while still give some introductions to the genre of the popular dramas.

Transference of 腐 from other cultures

In the case of 腐, the dictionary and conventional meanings were updated with meanings from Japanese culture. The official meaning is still present and has not been forgotten or distorted. Readers can easily distinguish the use of 腐 in different contexts and adopt the corresponding interpretation.

The new meaning of 腐 in Chinese pop culture is derived from the Japanese term "Fujoshi" (ふじょし). In the pre-modern era, Kanji were introduced to Japan from China, and are still used in everyday life in contemporary Japan. 腐 is written in Japanese Kanji as "腐女子", which was confirmed to be used on the Internet in the late 1990s and became generally accepted in 2005.[12] In the early 2000s, the spread of Japanese anime, idol groups, and manga in China brought the concept of 腐 with them. The similarity of the Kanji led early adopters of Japanese culture choose not to translate the Japanese word 腐 into its Chinese counterpart, but to adapt the Japanese definition and derivation.

Social, cultural, and political problems

Social Problems

The BL novels usually leave the readers with a rich imaginary space. Readers can imagine the appearance of male characters in novels according to their own aesthetic characteristics. The appearance of male actors appearing in homosexual dramas/BL dramas and movies is also able to meet the aesthetics of a wider audience. Such kind of environment will lead the audience's aesthetic to idealize homosexual images and relationships in the real life.[13] In order to satisfy cultural consumers, rotten culture has caused rotten women and rotten men who do not know enough about real homosexuals to have an unrealistic stereotype of the gay community. However, this stereotype will make some of them only accept the fictional homosexuality but not the homosexuality in the real life. The age range of readers of BL novels in China is from 11 to 30 years old.[14] A very large number of teenagers are already exposed to literature related to homosexuality. College-age women seem to be in the majority, but the number of middle and high school fans looks to be increasing.[14] Some researchers are concerned that the widespread dissemination of BL in society may have a negative impact on young people's sexual identity and gender perceptions.[15]

It is also worth observing that the female gaze in Danmei literature changes the dominance of men in traditional heterosexual romance novels. The male in Danmei literature is not only characterized by the dominance in traditional heterosexual fiction, but also appears in the form of dependency. This kind of literary creation allows cultural producers and consumers to feel themselves playing with patriarchal gender structures.[14] This escapist creation of romantic stories is also the reason why Danmei novels are becoming increasingly popular in current society.[14]

Cultural Problems

A significant reason for the growing awareness and tolerance of sexual minorities in mainland Chinese society can be attributed to the rise and development of Fu culture.[15] Queer is a generic term that denotes not only the sexuality and identity of sexual and gender minorities, but also some ideologies that challenge social structures.[16] Thus, queer includes sexual and non-sexual minorities who are seen as troublemakers in China's otherwise harmonious society.[16] Although the lack of proper guidance of rotten cultural consumers can cause some problems in society, the rotten culture has allowed the queer community's to be seen by more people. Nowadays, queer culture is no longer a topic that can only be talked about in the shadows and corners. Before the 1970s, there was no full-length Chinese modern queer novel.[17] The popularity of gay literature in China began to appear in the Chinese-speaking public field in the 1970s.[18] Starting in the 1980s, it began to reach a wider group of people. In 1983, Taiwanese author Pai Hsien-yung's Crystal Boys (Niezi) was published and is recognized as the first Chinese modern queer novel.[17] In current mainland China, there is not only legal silence on the issue of homosexuality, but homosexuality is socially unpopular and often censored in the mainstream media.[19] But as the rotten culture has gradually become popular culture, more people in a limited space have learned about this group through the media. The real gay couples that can be seen through social media can make some people who did not accept it drop their prejudices or bias after getting to know them.

Political Problems

BL fanaticism promotes a kind of gender politics.[14] Through Danmei literature, female readers are able to turn the "voyeuristic" gaze on men, a subversive gaze that allows rotten culture cultural producers and consumers to play with patriarchal gender structures. The dismantling of patriarchal domination in this gender politics of rotten culture provides female cultural producers and consumers with an escape from reality and creates an aesthetic that offers an alternative to the clichéd heterosexual romance. Since most BL novels are banned from publication in mainland China, much of the rotten cultural literature has been circulating on the Internet. However, this still does not stop the fanatic rotten culture lovers.[14] Fanaticism as a tool that can be used against hegemony. In the digital era, the feminism that can be embodied in rotten cultural literature reaches more gender equality in gender politics. Rotten culture satisfies the female needs for sexual appeal but eschews the male gaze. Female cultural consumers challenge the hierarchical gender order in society through reading, and are given the manipulation to male roles in the world of sexual fantasy.[20] Since a lot of Danmei literature is circulating online, many studies prove that digital media has a good potential to mobilize feminism, promote gender equality awareness and encourage gender political movements.[20]

Chinese censorship also affects the ways in which Chinese Danmei is shared and consumed. Although there are currently no laws in opposition to homosexuality or the existence of Danmei in China, pornographic material is against the law. Government crackdowns on pornographic material have lead to the arrest of numerous Danmei/BL artists who depict sexual imagery in their stories. [14][4] This does not do much to curb the proliferation and growing popularity of Danmei however, as some Danmei distribution websites, like Jinjiang Literature, avoid unwanted attention by remaining low-profile or exclusive to certain members. Even BL content that does not contain explicit sexual imagery is affected by Chinese censorship sometimes. Widely popular Danmei novel, Mo Dao Zu Shi (known in English as Grandmaster of Demonic Cultivation) by Mo Xiang Tong Xiu, has received multiple adaptations into different media forms such as an animated series, a live action series, and a comic, yet many of these adaptations deliberately do not show romance between the two lead male characters, particularly the television program adaptations. This avoidance of overt queer romance suggests that homosexuality is not fit to be shown on Chinese television. [4]

Gender and Sexuality Studies

Why is Chinese Danmei Popular Amongst Women?

Much scholarship on Chinese 腐 culture and the 腐女 (Fǔ nǚ) movement already exists, especially extensive discussion surrounding the gender and sexuality perspectives. Most studies on the readership of Chinese Danmei confirm that majority of active fans are females and a high percentage of these females are in fact heterosexual. [3][21] This brings up the question of why so many straight women find themselves devoting their free time to queer fiction between two men. Many scholars investigate the reasons for the explosive popularity of Danmei and BL amongst female readers, finding that factors such as the ability for female readers/viewers to temporarily escape from the normalized sexualization of women in everyday life contribute to the popularity of Danmei. Danmei and BL focus heavily on relationships between men, ensuring that instances of female sexualization are lessened. Not only this, but Danmei allows for female readers to explore their own sexual fantasies and pleasure, a generally taboo idea in conservative Chinese society. [14]

Being that women generally fall victim to objectification in popular media, Danmei and 腐 culture allegedly subverts this objectification. Written primarily for the female gaze, Danmei fiction lets women “enjoy the subversive thrill of watching males in a vulnerable, submissive position, not only sexually but emotionally.” [22] In this sense, the woman becomes the "sexualizer" instead of the "sexualized" for once. Although primarily seeming paradoxical, the popularity of Danmei amongst heterosexual female readers is logical in the sense that Danmei fiction depicts romance that, unlike heterosexual romance fiction, involves not only one but two handsome men. Many Danmei manhua artists also develop very aesthetically beautiful art styles, making many of the story's characters pleasing to look at. A participant in Chunyu Zhang's study on Chinese fǔ nǚ echoes this notion, saying that her love for BL simply means that she loves boys "twice as much" (p. 255) [14]

Heteronormativity in Chinese Danmei, BL, and 腐 Culture

Researchers also cite the popularity of Danmei and BL in Chinese pop culture to Danmei’s portrayal of supposedly more egalitarian relationships, less gendered power dynamics, and general radicalism when compared to heterosexual romance but other researchers have undergone studies which rebuke this claim. One study, Still a Hetero-Gendered World: A Content Analysis of Gender Stereotypes and Romantic Ideals in Chinese Boy Love Stories done by Yanyan Zhou et. al., analyzes the nature of gender stereotypes in 87 randomly sampled Chinese Danmei stories, finding that more often than not, Chinese Danmei and BL still adhere to heteronormative practices of associating masculinity with dominance and femininity with submission. [23]

Danmei and BL often depict relationships where one man acts as a traditional masculinity figure that is romantically and sexually dominant over his more feminine love interest. This character dichotomy trope is widely known as "seme-uke" which are Japanese terms for "attacker" (seme) and "receiver" (uke). [23] In Chinese, this character dichotomy is known as 攻受 (Pinyin: gōng shòu), 功 meaning "attacker" and 受 meaning "receiver."[24] "Gong" characters portray typically masculine traits such as being aggressive, physically strong, and financially providing for their partner while the "shou" character reflects stereotypical traits associated with femininity, such as being gentle, emotional, naïve, and dependent on their partner. [25] As such, the gendered stereotypes between the physical features and personality traits of "gong" and "shou" characters is criticized as a result of patriarchal gender hierarchy. [26] Although Chinese 腐 culture and Danmei might be inherently radical in the sense that queer fiction challenges the social norms of mainstream Chinese society, research shows that the content of these types of fiction still often conform to heteronormative ideas of gender.

Translations of BL into Real Life

Other researchers examine the ways in which Chinese Danmei readers interact with Danmei stories, investigating the voyeuristic female gaze and how this form of entertainment consumption translates into everyday life. One such research study explores the social attitudes of Danmei fans from Mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. The research found that Danmei fans or fǔ nǚ are much more accepting and supportive of homosexual relationships in real life than the general Chinese public. Interestingly enough, the results show that the study participants were slightly more accepting of male-male relationships than female-female relationships. [3] However, when compared to Anglophone BL fans and BL fans who are from the West, Chinese Danmei fans and fǔ nǚ show comparatively lower acceptance of homosexual relationships in real life. This might indicate that although generally having more radical mindsets than most of the Chinese public, Chinese Danmei fans still "may support central expectations of heterosexuality in Chinese culture" (p. 451). [27] Some research might suggest that some Chinese Danmei fans might be a little too accepting of real-life queer relationships. The previously mentioned study done by Zhang found that Chinese female Danmei readers often extend the voyeuristic gaze that they put onto the male characters of Danmei fiction onto men in real life as well. This manifests itself in the form of “cyberstalking” gay people on social media, classifying male classmates or coworkers as "seme" or "uke,"[3] or fantasizing about two men being together without even first considering their actual sexual orientations. Being that most female Danmei readers are heterosexual themselves, the researcher criticizes this practice as “a new form of heterosexual privilege that appropriates and exploits marginalized identities and experiences for personal curiosity" (p. 254). [14]

Sociological Studies and (In)Visibility of 腐 Culture

Differences Amongst 腐 Culture in Japan and China

The prominence of Chinese Danmei fiction is limited to certain areas due to social stigmatization amongst the general public who holds comparatively conservative views surrounding this form of entertainment. Especially when compared to Japan which is known as the origin of BL fiction and culture, Chinese Danmei appears to be much more confined to the Internet and cyberspace. In Japan, BL is considerably more normalized amongst mainstream culture, allowing Japanese fujoshi ("rotten woman" in Japanese) to be able to participate in offline events and gatherings related to their interests. A study done by Emily Williams compares Japanese BL culture and Chinese Danmei culture, mentioning that places like conventions and character cafés (similar to maid cafés) in Japan are spaces where fujoshi are welcomed and can meet with other like-minded individuals to discuss their favourite BL and have fun. The distribution and purchase of officially published BL novels and manga as well as fan-made dōjinshi (fan-made manga) are available in many places in Japan. [4]

In contrast, Chinese 腐 culture, the fǔ nǚ community, and Chinese Danmei fiction primarily operates in a virtual space. The usage of online platforms to distribute and consume Danmei and queer fiction enable Chinese fǔ nǚ to have greater control over anonymity and keeping their interests separate from their offline lives or jobs. [4] In addition to increased anonymity, Chinese Danmei's proliferation in an online space also allows for Danmei readers and fǔ nǚ to have more in-depth discussion in online forums about ongoing fiction which enables the fans provide to feedback and even influence the outcome of the story. [4] In this sense, many fǔ nǚ and BL fans are both producers and consumers of Danmei fiction.

Fujoshi and Fǔ Nǚ Identity

Despite being more mainstream in certain areas of the world, researchers still find that stigmatization surrounding fujoshi and fǔ nǚ exist almost everywhere. A study done on Japanese fujoshi identity examines the ways in which BL fans both conceal and reveal their identity as a fujoshi to others. Because of the viewing of 腐 culture and BL fiction as deviant or unusual by mainstream society, an avid BL and Danmei fan usually feels that they must conceal their interests in order to appear like a "normal woman." Borrowing sociological identity theory from sociologist, Erving Goffman, researchers Okabe and Ishida argue that identity concealment is a central part of fujoshi identity construction, and "[i]n this sense, fujoshi is a category constructed through a complex set of practices of visibility and invisibility" (p. 218). [28] Because identity concealment is a common practice amongst many fujoshi and fǔ nǚ, it can conversely be seen as a method of revealing to other fellow fujoshi and fǔ nǚ, as identity concealment is often a topic of conversation and a mutual experience for the 腐 culture community. Moreover, being aware of the stigmatization surrounding 腐 culture, many fujoshi and fǔ nǚ cope by participating in self-deprecating or ironic humour by making fun of their hobbies, way of dress, and so on. Okabe and Ishida believe that this sense of ironic humour and self-punishment is unique to fujoshi and fǔ nǚ identity construction and is a way to deflect the negative social consequences and criticisms directed towards individuals who actively consume Danmei fiction and participate in 腐 culture. [28]

Conclusion

In general, the word "腐" is used very frequently in Chinese words and expressions, and is active in people's eyes with a wide range of meanings. The word, "腐," encompasses a wide range of practices, hobbies, and identities that represent a very unique community of people in China as well as across the world. There exist certain some negative attitudes towards the 腐 culture community due to the perceived deviancy of consuming queer media, especially in Chinese society which is still quite conservative compared to other areas of the world. The meaning of the word "腐" is used to study the sexual orientation and social identity of individuals. Despite the limitation of 腐 culture visibility in Chinese society due to factors such as social stigmatization as well as censorship, the popularity of 腐 content, products, and fiction continues to grow, especially within the realm of the Internet. Although 腐 culture in China might not be as commercially prominent as in places such as Japan, it remains a culture that continues to gain traction within the younger Chinese generation. Providing an outlet for females to escape from misogyny, targeted sexualization, and gender inequality within media as well as allowing space for the exploration of sexualization using the female gaze, it is no wonder that 腐 culture, Danmei, and BL fiction have become popular. [14] With the popularity of "腐", other words such as "反腐" (Pinyin: Fǎnfǔ, English: anti-corruption) and "腐女" (Pinyin: Fǔ nǚ, English: "rotten woman") have also become popular, and there even exist anti-corruption TV dramas like In the Name of the People, further developing the film and television industry. By studying the transformation and meaning of these popular terms, people can gain a deeper understanding of behaviours and policies regarding "腐" culture in Chinese society.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Meaning of 腐". Purple Culture.

- ↑ Tian, Xi (March 1, 2020). "Homosexualizing "Boys Love" in China: Reflexivity, Genre Transformation, and Cultural Interaction". Prism. 17: 103–126 – via Duke University Press.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Madill, Anna; Zhao, Yao (2021). "Engagement with female-oriented male-male erotica in Mainland China and Hong Kong: Fandom intensity, social outlook, and region" (PDF). Journal of Audience and Reception Studies. 18: 111–131 – via White Rose.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Williams, Emily, "BL and Danmei The Similarities and Differences Between Male x Male Content and its Fans in Japan and China" (2020). Honors Projects. 501. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/honorsprojects/501

- ↑ Yang, Ling; Xu, Yanrui (May 5, 2016). "Danmei, Xianqing, and the making of a queer online public sphere in China". Communication and the Public. 1: 251–256 – via Sage Journals.

- ↑ "腐". TrainChinese.

- ↑ "腐 Character Etymology". Yellow Bridge.

- ↑ "Fu nv Chat Room (if you're not a fan of fu, don't click)". Baidu Tieba.

- ↑ "Zhu Yilong won the Golden Rooster Award for best actor, some people are not convinced".

- ↑ 서경원 and 김용균. "日本大衆文化における「腐女子」に関する一考察". 일본근대학연구. 47: 307–322.

- ↑ "全网最全,2020年已播60部腐剧盘点".

- ↑ 서경원 and 김용균. "日本大衆文化における「腐女子」に関する一考察". 일본근대학연구.

- ↑ Lilja, Mona; Wasshede, Cathrin (2017-02-28). "The Performative Force of Cultural Products: Subject Positions and Desires Emerging From Engagement with the Manga Boys' Love and Yaoi".

- ↑ 14.00 14.01 14.02 14.03 14.04 14.05 14.06 14.07 14.08 14.09 14.10 Zhang, Chunyu (August 2, 2016). "Loving Boys Twice as Much: Chinese Women's Paradoxical Fandom of "Boys' Love" Fiction". Women's Studies in Communication. 39: 246–267 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Madill, Anna; Zhao, Yao; Fan, Liheng (20 Sep 2018). "Male‒male marriage in Sinophone and Anglophone Harry Potter danmei and slash".

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Zhao, Jamie J. (18 Jun 2020). "It has never been "normal": queer pop in post-2000 China".

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Liu, Petrus (Number 2, 2010). "Why Does Queer Theory Need China?". Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Wong, Alvin K. (24 Jun 2020). "Towards a queer affective economy of boys' love in contemporary Chinese media".

- ↑ Madill, Anna; Zhao, Yao (16 Apr 2021). "Engagement with Female-oriented Male–Male Incest Erotica: A Comparison of Sinophone and Anglophone Boys' Love Fandom".

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Chang, Jiang; Tian, Hao (11 Aug 2020). "Girl power in boy love: Yaoi, online female counterculture, and digital feminism in China".

- ↑ Li, Yannan (July, 2009). Japanese Boy-Love Manga and the Global Fandom: A Case Study of Chinese Female Readers (PDF). (Thesis). Indiana University.

- ↑ Kee, Tan Bee (2010). "Rewriting gender and sexuality in English-language yaoi fandom". Boys' love manga: Essays on the sexual ambiguity and cross-cultural fandom of the genre. North Carolina: McFarland. p. 140. ISBN 978-0786441952.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Zhou, Yanyan; Bryant, Paul; Sherman, Ryland (April 1, 2017). "Still a Hetero-Gendered World: A Content Analysis of Gender Stereotypes and Romantic Ideals in Chinese Boy Love Stories". Sex Roles. 78: 107–118 – via Springer Link.

- ↑ Liang, Yuan (2019). "Women in Transition: Analyzing Female-Oriented Danmei Fiction in Contemporary China" (PDF). Two Cases of Chinese Internet Studies (Thesis). Cornell University.

- ↑ McLelland, Mark (2000). "No climax, no point, no meaning? Japanese women's Boy-Love sites. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 24(3), 274-291". Journal of Communication. 24: 274–291 – via Sage Journals.

- ↑ Pagliassotti, Dru (2010). "Better than romance? Japanese BL manga and the subgenre of male/male romantic fiction". Boys’ love manga: Essays on the sexual ambiguity and cross-cultural fandom of the genre. North Carolina: McFarland. pp. 59–83. ISBN 978-0786441952.

- ↑ Madill, Anna; Zhao, Yao (September 17, 2018). "The heteronormative frame in Chinese Yaoi: integrating female Chinese fan interviews with Sinophone and Anglophone survey data". Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics. 9: 435–457 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Okabe, Daisuke; Ishida, Kimi (2012). "Making Fujoshi Identity Visible And Invisible". Fandom Unbound. Yale University Press. pp. 207–224. ISBN 9780300178265.

| This resource was created by Course:ASIA319. |