Course:ASIA319/2022/"Alluring" (撩)

Introduction

撩 liao, a Chinese character loaded with multiple pronunciations and meanings, has existed in Chinese history for a long time. As a verb initially, 撩 describes the motion of stretching one's hands to do something and since then, has been utilized in describing other motions related to "stretching one's hands", such as to put in order, disorder, to pick up, and to stir up. Besides, 撩’s meaning is also extended as to tease or to allure in Chinese culture throughout history and is further used in contemporary Chinese popular culture to imply romantic interactions with sexual cues among people, especially between opposing genders. By exploring the evolvement, different meanings, and context of using 撩 in contemporary Chinese society, this entry examines the social, cultural, and political implications beneath its usage and how this Chinese character reflects the attitudes of Chinese people and Chinese society in the current era.

The genesis of the keyword

Throughout history, 撩 has had a myriad of different uses within literature and poetry. Beginning with poetry by Yuxin of the Northern Zhou Dynasty and Bianwen's "Swallow Poems”, 撩 reflected the notions of “to brush away” or “to tease”[1]. Its meaning was maintained throughout various Chinese dynasties and as it did, 撩 began to expand its definitions, one of which was "to attract" or "to flirt". In the Ming dynasty, a book called 杜骗新书 New Book of Du Lie was published with a collection of short stories which detailed various tricks and strategies its reader could use to court girls[2]. From the Ming dynasty to the modern age, 撩 maintained its other meanings but in the context of flirting, was seen as a short teasing flirt used to seduce your partner into romance. While its meaning started out as derogatory, the practice of teasing your lover is now viewed as a skill[2]. When the South Korean television series Descendants of the Sun came out in 2016, its popularity was explosive within Asia[2]. The main male lead in the show, Song Joong-ki (송중기), is a witty and attractive special forces soldier who not only possesses the traits that many found alluring—such as being handsome, fit, and having a traditionally masculine position as a soldier—but also appears to be a master of flirting with girls and an example of an exemplary flirtatious male[3]. Due to this, he was given the nickname of 宋会撩 Song Hui Liao which translates to "Song who knows how to flirt"[3], promoting the keyword 撩 as a term that embodies the humour, confidence, and mesmerizing nature of the male lead in his interactions with females. The popularity of Descendants of the Sun, dating shows, and social media’s love for buzzwords then gave birth to 撩妹 liaomei (flirting with the girls), the internet flirting culture that currently exists as the most popular use of 撩.

Glossary of its explicit dictionary meanings

Dictionary Meaning of 撩

The word "alluring", written as 撩 using Chinese characters, has three pronunciations in total, all with different meanings attached separately, but all sharing a certain degree of 撩's original meaning: stretching one's hands to do something.

When 撩 is pronounced as liāo, it mainly refers to some kind of motion related to "stretching one's hands", such as 撩开 liāo kai (to push aside clothing, curtain etc.), 撩起 liāo qǐ (to lift up curtains, clothing etc.)[4]

When 撩 is pronounced as liáo, it embodies mainly four meanings[5]:

- Put in order or arrange, such as 撩治 liáo zhì (deal with/handle/manage something), 撩理 liáo lǐ (tidy up; take care of).

- Wind or disorder, such as 撩绕 liáo rào (wrap around).

- Pick up, such as 撩摘 liáo zhāi (pick up).

- Incite/provoke/stir up, such as 撩虎须 liáo hǔ xū (take risks). This meaning has been extended as to stir up (emotions) and to tease, such as 撩逗 liáo dòu, and, in contemporary Chinese culture, 撩妹/撩汉 liáo mèi/liáo hàn (flirt with a girl/man).

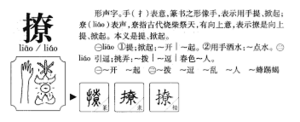

Etymology of 撩

This Chinese character is a semantic-phonetic compound character[5]. The structure of this Chinese character is composed of two parts: 扌 (hand) on the left side conveys half of the meaning while 尞 (burn/fuel in its original meaning but extended as long/distant)[4] [6] on the right side indicates the other half of the meaning and the sound. When combining the meaning of the two parts "hand" and "long/distant", the original meaning of 撩 (stretching one's hands) emerges [5].

撩 in Chinese Popular Culture: Multiple Meanings and Usages

Meanings and value-loaded implications

撩 liao serves an important role in contemporary Chinese popular culture, especially in domains about dating and courtship. The extended meaning of 撩 liao as to tease and to allure has existed in the history of this word for a long time and is associated with many words conveying similar messages. However, in recent years, some new words associated with 撩 liao have emerged on the Internet among Chinese netizens and have spread across people's daily life and conversations, such as 撩妹 liáo mèi (flirt with a girl). Today, when searching for "撩" on the biggest Chinese search engine Baidu, aside from the two dictionary websites at the top, the two proceeding results are "What's Your Interesting Experience about '撩' (flirting) or Being '撩' (flirted)?"[7] and "The Top Three Types of Women Men Love to 撩 (flirt with), and You Will Be Cheap If You Are One of Them"[8], indicating the overwhelmingly frequent use of 撩 liao with the meaning of to tease or to flirt with in contemporary Chinese popular culture.

Furthermore, in the "related searches" of this single Chinese character in Baidu, most of them are about 撩妹 liao mei, which is when men allure "girls". 撩妹's counterpart, 撩汉 liao hàn (women alluring men), only constitutes a minor part of the related searches. Although the related searches change every time, the 撩妹 searches are often more popular than 撩汉 searches, which implies that 撩 in contemporary Chinese popular culture is mostly used to describe males alluring females[9]. The usage of different Chinese characters when referring to the subject of being allured also varies with genders, such as using "girl/little sister (妹)" as female while using "man (汉)" as males. This alludes to certain problematic aspects of gender in contemporary Chinese popular culture.

Shared Body of Words Associated with 撩

Overall, there is a large shared body of words that can be associated with that of alluring, many of which have been created through the use of the word in different situations and contexts in popular Chinese culture and society. When trying to find a translation, we see several different variations of the word being used, changing situationally. In regards to the word itself, the character 撩 liao is read as the word “alluring” or "to flirt"[10]. However, that isn’t the only version of the word you may see used in the context of “alluring”. The word 吸引人的 Xīyǐn rén de can be used when describing a person or situation as attractive, or appealing, but is synonymous with the word “alluring” in Chinese. Conversely, the characters 诱惑的 Yòuhuò de can be used in a more adult context, meaning seductive, and 迷人的 Mírén de can be used when describing objects or situations as charming[11]. However, both these words are synonymous with our keyword “alluring”. Additionally, as highlighted above, 撩 has also been combined with 妹 mei or 汉 han to describe seducing a girl or a man. Hence, we can see that given changes in context, target gender, and situations, the word “alluring” can be used in many different ways in general conversations of Chinese popular culture and society.

Comparison and Summarization of the Multiple Meanings of 撩

Depending on which context the word is being used in, there are several distinctly related and also starkly different ideas and values implied by the multiple meanings of the word “alluring”. In a non-romantic context, the word is often used in conjunction with a fascination or interest in a particular idea, place, value, or thought. For example, we can often see the character 迷人的 Mírén de being used to describe objects or ideas as fascinating or attractive[12]. In Bai Zucheng’s excerpt in the Journal of Tourism for the Beijing Institute of Tourism, Bai uses the word “alluring” synonymously with “charming” in order to describe the glamorous image and products of Beijing[13]. Conversely, in situations where one is explaining the attractiveness of an idea or value in a non-sexualized context, the characters 吸引人的 Xīyǐn rén de are used[14]. Such as in Wei Shiye and Zhen Zhuanghai’s abstract on the problems of ideological and political work, they use the word alluring to describe the attractiveness of the issues associated with this work[15]. In these contexts, we can see the meaning of the word change slightly as the usage evolves from describing the abilities to be alluring in one case, such as charming visitors, to the simple state of just being alluring in another case, such as being attractive with regards to other potential options. The word alluring can also have multiple meanings represented in a range of ideas and values in a more sexualized context. In this regard, the word “alluring” is usually synonymous with “seductive” or “sexy”. However, depending on the conditions, it can also take on a less sexualized tone, instead, being used to mean “catching” or “lovely”. Using the words “seductive” in place of alluring is commonly observed in a lot in Hsiang’s Lectures on Chinese Poetry. For example, Wang associates his preference for female singers and their feminine lyrics in Hsiang’s Lectures, describing them as “lovely and seductive” using 婉媚 wanmei[16]. In this framework, we can see how the characters associated with the word “alluring” are often put in a feminine perspective when pertaining to sex or sexuality. This presents another interesting gendered aspect of the word “alluring” when associated targets or undertones are contextualized within a more sexualized framework. Hsiang’s lectures further explain this through a quote from Joseph Lam, describing that music made by women seduce its listeners not simply through sound, but through the physical presence of female performers[17]. Through this, we understand in Chinese popular culture how gender ideals shine through the use of associated words, especially when the target gender changes from male to female or vice versa.

In a sexualized context, alluring can also be used very negatively. For example, in Lu Jinzeng Wang and Jinhong Zhao Jian’s summary in the 11th issue of Legal System and Economics, the characters 勾引 Gōuyǐn are used to convey “alluring” as meaning “to seduce”[18]. This situation pertains to a woman seducing a man in order to extort money and sue for rape if her demands were not met. In this context, “alluring” is synonymous with “luring”, or “enticing”. We can assume that this character is hence used in situations where an individual hopes to gain more money and fame through the act of “alluring” or seducing another individual or group.

The Transfer, Distortion, and Subversion of 撩's Counterparts in Western or non-Chinese Popular Cultures

"Picking Up" in the West

One of the most popular uses of 撩 today is in pickup culture, a culture that revolves around phrases or lines that guarantee positive romantic results whether that be a cute play on words or lightly teasing your crush. Online, many websites offer hundreds of different pickup lines with some even using examples of successful text conversations to prove their proficiency[19]. In the West, this may be reminiscent of pick-up artistry which rose to prominence in the 1990s and 2000s. As opposed to a series of websites, pick-up artistry usually revolves around a singular “guru” who teaches strategies of seduction, including pickup lines, to their audience[20]. One common trend among both groups is that they advertise by “guaranteeing” success in attraction and treat their methods as being the best. These sources reinforce a culture of materiality by advertising the use of seductive phrases as a filler for personality traits such as self-improvement. There is also a gamification element to both these sites and what is promoted by gurus. For pick-up artists, this is quite literally “the game” of pickup culture for these websites also feature “walkthroughs” or a selected set of romantic quotes for differing situations (e.g. Conversational, Confessional, etc).

"Aegyo" in Korea (hangul: 애교, hanja: 愛嬌)

The term aegyo is a form of baby talk often used to communicate a sort of childlike cuteness when it comes to flirting in Korea. The traditional hanja terms 愛 ae (love) and 嬌 gyo (charming/bewitching) communicate a similar meaning to 撩 liao as both refer to a form of romantic charm[21]. In the context of flirting, aegyo is more commonly used to describe females who perform cute acts such as speaking in high pitched voice, making cute gestures, or displaying childish qualities—embodying a form of passive femininity[21]. This contrasts with 撩 liao which carries a more dark, mysterious, and tempting quality, especially when used to describe males. In some cases, aegyo is even seen as a virtue that Korean women should embody in order to attract care and attention from their male counterparts in a heterosexual relationship[22]. This phenomenon closely mirrors the trait-like aspect of 撩 liao which in contemporary Chinese culture, is a skill that youth are expected to be well versed in[2].

In the context of Korean popular culture, aegyo is commonly used by singers or pop stars to appeal to fans, as well as in shows or dramas between romantic partners. For example, in a popular variety show Family Entertainment, a member of the girl band Girls Generation performed aegyo in a skit with a male comedian where the male played the role of an angry partner whose emotions are placated by the female's aegyo appeal[23]. Here, aegyo reproduces traditional masculine and feminine gender norms whereby the males are seen as aggressive and active while females are seen as subservient. By using a child-like quality to appease the male, this downplays female authority and power, illustrating the problematic aspects of this form of flirting in contemporary Korean popular culture.

"Nampa" in Japan (Hiragana: なんぱ, Katakana: ナンパ, Kanji: 軟派)

The Japanese term Nampa is very similar to 撩 liao in that it reflects men seducing or picking up women[24]. The Kanji term means "soft party" and was used politically at first to describe moderate political parties that were unable to enact upon hard claims[25]. Similar to 撩 liao then, Nampa started out as a rather derogatory term that later absorbed various meanings through its use. In the context of dating, Nampa was first associated with young people who date fashionable women before later turning into the act of attracting or flirting with women[24]. Just as 撩妹 Liaomei (men alluring girls/women) has 撩汉 liaohan (women alluring boys/men), Japanese Nampa culture also has its counterpart which literally translates to the reverse of Nampa. Gyakunan (软派) is the culture of groups of women traveling together seeking a man or multiple men. Their intentions are as un-serious as groups of Nampa males in that they do not seek long-term attachment and instead, aim to either spend their time with the male when they first meet or exchange numbers to meet at a later date. Both Nampa and Gyakunan are also believed to be skills required to attract a possible partner, that of which cannot be achieved by simply flashing money in their face.[26]

Social, cultural, and political problems

Social context of 撩: Gender Issues

In contemporary Chinese society, the term 撩 liao perpetuates various hegemonic social norms around beauty standards, gender, romantic relationships, and courtship etiquette, while reflecting modern-day attitudes towards dating and marriage. As heard across various dating shows in China, namely If You are the One and New Chinese Dating Time, 撩 liao often appears in a heterosexual context describing male participants who are conventionally attractive. The participants who succeed in “alluring” the female often possess traits such as being tall, handsome, fit, economically secure, and confident enough to confess their love on stage. In fact, during the initial release of If You are the One, the show encouraged the display of materialistic qualities—such as owning a car, house, or possessing high income—from their male participants and shaped these discourses into key factors of their attractiveness[27]. Not only does this perpetuate unhealthy images of masculinity, but it also reinforces unequal gendered stereotypes that prescribe a male breadwinner role and the notion that females must be provided for and dependent upon their male partners. In fact, in an interview with young students at Nanjing University, most expressed how the ideal bride should be intelligent, gentle, caring, and pretty while the ideal husband should provide for the family by bearing marriage expenses and housing costs[28]. Unsurprisingly, this reflects the broader social norm where women marry up and men marry down. Even by comparing 撩妹 liao mei (flirting with the girl) versus 撩汉 liao han (flirting with the man), the fact that females assume the role of a "little girl" and the males assume the role of a "man" perpetuate the heteronormative and patriarchal relationship standards that characterize romantic ideals in contemporary Chinese society.

Given that males more commonly take initiative in attracting their female counterparts, one must question what happens when this gender dynamic is challenged. With females having gained increasingly more independence, economic freedom, educational attainment, and equality across various spheres of life, it is interesting that within the sphere of dating and courtship, patriarchal norms prevail. Primarily, professional career women, especially in their thirties or older, find little success in the dating market due to their divergence from traditional cultural stereotypes[29]. For example, female academics in China are labelled as 女博士, or “female PhD”, which presumes that they are “sexless, odd, and unattractive”[29]. For women then, their attractiveness does not stem from how much they achieve. Instead, their alluringness stems from their physical traits. This stands in stark contrast with the qualities that make males alluring—namely high educational attainment, high income, and professional careers. That the same achievements, when applied to different genders, results in completely opposing attitudes reflect society’s unequal expectations towards how Chinese women and men should act and the patriarchally-situated societal qualities that dictate their respective romantic attractiveness and suitability. Hence, within the context of contemporary Chinese popular culture, 撩 liao is a term that reflects problematic hegemonic gender ideals, conventions of beauty and attraction, and heteronormative relationship standards.

Cultural context of 撩: Dating Attitudes

Culturally, 撩 liao must also be contextualized within the attitudes towards dating and courtship in China. Contrary to America where dating is normalized among school-aged youth as a coming of age experience, as a culture that highly values academic success, dating among students is shunned in Chinese culture as many parents view dating as an inhibitor to students’ learning[30]. This early suppression of romantic expression often translates to inexperience or shyness in courtship later on in one’s life[31]. Given that 撩 liao became popular as a result of the famous Korean drama Descendants of the Sun where the male lead, coined a “god of flirting”, was seen as a character that young men should learn from[2], it accurately reflects young people’s desire to embody the confidence and attractiveness that the male lead displayed when it comes to their own experiences with flirting. With early conversations around dating silenced by youth’s expectation to fulfill their filial duties of being a good student, learning courtship etiquette from dramas becomes a solution that youth turn towards. The desire to learn about dating, therefore, popularizes the word 撩 liao. While the phenomenon of dating later is by no means problematic in any way, what this potentially engenders is a lack of conversation around healthy relationships and the desire instead for youth to hide their romantic experiences from their families. Furthered by the fact that schools in China have policies around limiting romantic activity among their students[30], youth turn towards online platforms as a means of seeking information and engaging with the discourse around dating. However, with both dating and sexual activity increasing among youth in China[30], the existing avoidant and repressive attitudes towards dating could potentially stifle the space for open conversations around what safe and healthy romantic and sexual relationships embody.

Political context of 撩: Politician Image, Regulation of Media

In recent years the term 撩 liao has received interest from politicians who use the term to appeal to a younger voting audience. Politicians such as Taiwan’s president Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文) and Ting Shou-Chung (丁守中) have taken part in the internet trend of 撩妹 liao mei or “flirt with the girls” in which they have shared their go-to pickup lines[32][33]. Their intention is to seem more approachable among their supporters, and this can be seen through politicians giving less formal interviews or posting on social media such as Instagram. While the word has had small amounts of influence regarding political issues in mainstream media, it has been used to criticize politicians for masking their intentions or being adulterous. The word has not been received positively in the political world but rather, is a term more delegated to private life.

Furthermore, there have also been political implications around the media reproduction of ideals of masculinity and femininity. Due to the rampant materialism that was being promoted on the dating show If You Are The One which glorified wealthy males who owned cars or a home while downplaying those who didn’t, concerns surrounding the promotion of “vulga[r] and negative values” that “deviat[ed] from the socialist core value system” led to the regulation of dating shows in China[27]. This included shedding a positive light on male participants’ talents and personality over materialistic qualities while also leveraging the opportunity to discipline females to refrain from being “gold diggers”[27]—people who only pursue a romantic relationship for their partner’s money. Hence, amidst changing gender norms and courtship practices, the qualities of attractiveness and alluringness have been political shaped to fit the socialist ideology.

Linguistical approach to 撩

From a linguistic studies point of view, the term 撩 liao is advantageous in several ways. As Zhuang summarizes in her study of the internet meme of 撩妹 liaomei (flirting with the sisters), 撩 liao is semantically rich, with meaning varying from emotionally attracting girls, to displaying oneself attractively, to flirting, to probing or gauging the other party’s reaction to one’s romantic advances[2]. Hence, its widely applicable status makes it easily replicable across many contexts, contributing to its popularity in China’s meme culture. Zhuang also states how the word 撩妹 liaomei is especially easy to recognize as it conforms to the typical verb-object structure that is pervasive within the Chinese language structure[2]. The semantics of 撩妹 liaomei, although initially reflecting a derogatory and provocative term that has roots in dialects such as Cantonese, Hakka, and ones in the Fuzhou region, after its popularity, has shifted meanings to encompass one’s intelligence, wittiness, and confidence when it comes to flirting[3]. This expansion of semantic meaning illustrates how language, as a reflection of culture, is constantly shaped by social forces in a way that challenges, expands, and engages with existing hegemonic ideas and beliefs. In fact, although 撩妹 liaomei reflects the unequal gendered aspects of courtship and flirting, new terms such as 撩哥 liao ge, 撩弟 liao di, or 撩汉 liao han have also emerged to reflect the normalization of women initiating in courtship[3]. This linguistical expansion of the existing gendered term to encompass greater gender equality reflects the changing social attitudes towards women being confident and capable of being active players in pursuing the romance that they desire. Therefore, these linguistical perspectives can reveal physical drivers behind a word’s popularity by shedding light on the inapparent aspects of our everyday language—such as syntax, semantics, and pragmatics—that shape how we engage with and reproduce popular cultural artifacts.

Socio-psychological approach to 撩

The popularity of 撩 liao can also be rooted in socio-psychological phenomena. Li explores in her paper how 撩 liao not only reflects the online era’s constant desire for novelty but also Chinese individuals’ coping mechanism with the stressors of modern city life[34]. As 撩 liao embodies several meanings including provoking, teasing, flirting, chasing, and attracting, it presents a means of stimulating one’s mundane life where fulfillment and joy appear distant from the harsh realities of urbanity. Translated directly, 撩’s popularity can be attributed to the “social and cultural psychology…of individuality, unconventionality, and traceability”[34]. These dynamic forces represent the many intersecting values experienced by the Chinese youth and young adults who dominate the internet space as they juggle with the complexities of Western individualistic influence, nationalism and cultural heritage, and growing competition. Their desire to distinguish themselves while also fitting in with the popular masses breeds a space for 撩 liao to gain popularity as a word that embodies similar sentiments of subtle excitement without being overly invigorating. Therefore, this socio-psychological perspective on 撩 liao reveals the complex interrelation between the social circumstances of modern China, its resulting psychological effects on modern youth, and how these states contribute to the popularization of 撩 liao on the internet.

Conclusion

撩 liao has come to embody a number of meanings stemming from very distinct yet associated contexts and situations in contemporary Chinese popular culture. After being made popular through Descendants of the Sun, this vocabulary has evolved from simply meaning alluring, to include a wide variety of synonyms, such as seductive, teasing, attractive, engaging and tempting to name a few. Often, it is used with the word 妹 mei to reflect the act of flirting with a girl. Conversely, the usage of the word “alluring” has continued to grow into several implied meanings throughout the history of its usage both in China and globally, with its most popular usages in today's popular culture and general conversation represented as being appealing or attractive to interact with, whether it be through smell, touch, or taste.

Socially, culturally, and politically, 撩 is loaded with normative implications surrounding gender, dating attitudes, and courtship etiquette. First and foremost, as 撩 is often used to refer to males, it perpetuates hegemonic gender ideals surrounding masculine traits that are prized as attractive. This inherently reinforces notions of female passivity as well as negative stereotypes towards females who have upset this gender dynamic through their own successful economic or educational attainments. Regarding dating, 撩 also reflects modern-day youth’s explorative curiosity around courtship and demonstrates the desire for youth in China to embody confidence in one’s romantic pursuits. In the realm of politics, 撩 has been leveraged by politicians to appeal to the younger voting audience.

Linguistically, 撩’s semantic broadness helps make it widely applicable and replicable across various aspects of pop culture. Its changing meanings, from a vulgar term to one that reflected positive characteristics that one should embody in courtship, demonstrates the profound influence of culture on the reshaping of words’ significance. Socio-psychologically, 撩 also reflects a lighthearted and fun word that contrasts with the harsh demands of modern urban life such as long work hours, growing inequality, growing competition, and increased costs of living. These interdisciplinary studies ultimately reveal the complexity of the popular keyword, 撩, and the various cultural, political, and social forces that shape its use.

As this work focused mainly on flirting in Chinese culture, future studies could delve into dating and courtship practices within other East Asian cultures. In particular, it would be beneficial to note how the problematic aspects of gendered relations implied through the word 撩 appear in places like Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. As many of these East Asian cultures share ideological roots in Confucianism, one could examine how modern-day practices of courting either draw upon or reject historical cultural norms.

References

- ↑ "撩". Multi Function Chinese Character Database. July 2014.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Zhuang, Meiying (August 2017). "A Memetic Interpretation of the Internet Buzzword "Liumei"". Journal of Qiannan Normal University for Nationalities. 37: 38–40 – via www.cnki.net.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Yan, Yumeng (2018). "The Semantic Evolution and Standardized Use of "Liaomei"". Northern Literature. 18: 231 – via www.cnki.net.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Meaning of 撩". Purple Culture 紫萱文化.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "撩 Alluring (Chinese Character)". Baidu Baike.

- ↑ "尞 burn/fuel (Chinese character)". Baidu Baike.

- ↑ "你有哪些有趣的「撩」或「被撩」的经历?". Zhihu.

- ↑ "男人最喜欢"撩"的就是这三种女人,哪怕占一个,你就"廉价"了". Baidu.

- ↑ "Search "撩" in Baidu". Baidu.

- ↑ "撩". Wiktionary. March 19th, 2022. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "ALLURING". bab.la. March 19th, 2022. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "ALLURING". bab.la. March 19th, 2022. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Zucheng, Bai (1994). "Build Beijing's beautiful and charming tourism image and optimize Beijing's unique tourism products".

- ↑ "ALLURING". bab.la. March 19th, 2022. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Shiye, Zhuanghai, Wei, Shen (March 19th, 2022). "The ideological and political work should solve attractive problems". Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Hsiang, Paul (2008). "Hsiang Lectures on Chinese Poetry".

- ↑ Hsiang, Paul (2008). "Hsiang Lectures on Chinese Poetry".

- ↑ Wang, Jian, Lu Jinzeng, Wang Jinhong (November 2012). "Woman seduces married man to extort "youth compensation" and sue for rape if not paid".

- ↑ "In 2021, we have selected 50 quotes about flirting with girls, to ensure that you can strike up a conversation and confess successfully!".

- ↑ King, Andrew Stephen (November 2017). "Feminism's Flip Side: A Cultural History of the Pickup Artist". Sexuality & Culture. 22: 299–315 – via Springer Link.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Puzar, Aljosa; Hong, Yewon (June 2018). "Korean Cuties: Understanding Performed Winsomeness (Aegyo) in South Korea". The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology. 19: 333–349 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- ↑ Jang, Hayeun (January 2021). "How cute do I sound to you?: gender and age effects in the use and evaluation of Korean baby-talk register, Aegyo". https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2020.101289. 83 – via Elsevier Science Direct. External link in

|journal=(help) - ↑ Brown, Lucien (March 2017). ""Nwuna׳s body is so sexy": Pop culture and the chronotopic formulations of kinship terms in Korean". Discourse, Context & Media. 15: 1–10 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 "Meaning of Nampa".

- ↑ "Nampa".

- ↑ ""软派 Soft faction (Japanese Character)"". Baidu Baike.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Chen, Siyu (January 2017). "Disciplining Desiring Subjects through the Remodeling of Masculinity: A Case Study of a Chinese Reality Dating Show". Modern China. 43: 95–120 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Zavoretti, Roberta (July 2016). [doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X15000220 "Is it Better to Cry in a BMW or to Laugh on a Bicycle? Marriage, 'financial performance anxiety', and the production of class in Nanjing"] Check

|url=value (help). Modern Asian Studies. 50: 1190–1219 – via ProQuest. - ↑ 29.0 29.1 Zheng, Jing (2019). "Doing Gender in Commodification of Courtship and Dating: Understanding Women's Experiences of Attending Commercialized Matchmaking Activities in China". Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies. 40: 176–199 – via Project MUSE.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Madigan, Timothy J.; Blair, Sampson L. (October 13, 2020). "Dating attitudes and behaviors of American and Chinese college students: A partial replication". The Social Science Journal – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- ↑ Hershatter, Gail (Summer 1984). "Making a Friend: Changing Patterns of Courtship in Urban China". Pacific Affairs. 57: 237–251 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Zeng, Shiting (July 2018). ""Politician's version of flirting quotes" was omitted, and Ding Shouzhong opened his mouth. His golden phrase for flirting with girls is..."

- ↑ Flynn (December 2019). "In order to win the support of young Taiwanese voters, Tsai Ing-wen frequently took pictures with Internet celebrities and was willing to be "sister"".

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Li, Xin Sheng (2019). "On "Liao (Flirt)"". Journal of Tangshan Normal University. 41: 13–16 – via www.cnki.net.

| This resource was created by Course:ASIA319. |