Course:ASIA319/2022/"Meat" (肉)

Introduction

The original meaning of 肉 (rou) is commonly used as a word to describe meat and flesh. It is also used as a dialect to express the character of slow-moving in some regions of China. Recently, the term 小鮮肉 (Xiao Xian Rou), which refers to androgynous, young males with a well-organized face, has been used as Chinese Internet slang and is gaining attention. It covers males who reflect feminine cultural beauty such as skin whitening and slender physique as its characteristics and is the ideal male image of the new generation in China. Since the popularity of Korean K-POP boys in China has increased with the spread of the Internet, this has brought about a major change from the conventional conception of tough, muscular males as good-looking. [1] The celebrities rated as Xiao Xian Rou are in high demand among a majority of young millennial consumers in China and are hired by a large number of companies both in China and abroad, making them an important element in marketing. [2] For the purpose of studying xiao xian rou to examine how the concept affects popular culture, interacts politically and culturally in Chinese society, and clarifies the changing nature of gender in China.

The genesis of the keyword

Throughout the years, there have since been a shift in preference and the rise of popularity of the word “little fresh meat” or “Xiao Xian Rou”. This word depicts a new trend where Chinese popular culture is shifting from the tough guy that is usually portrayed by male artists to more beautiful androgynous men. Little fresh meat focuses on a recent phenomenon, which are young male actors embodying a feminime beauty. [2]

This trend of little fresh meats had been apparent for a couple of years, especially referencing other country’s entertainment talents, such as K-Pop and J-Pop. This new form of softer masculinity appeals more towards the female millennials and their romantic preferences. From these new trends, especially with the increasing popularity of the hit Chinese television series, Meteor Garden, "Little Fresh Meats" in the Chinese entertainment industry have grown more popular as they have a large amount of followers, an abundance of advertisement deals, and scoring top roles in movies and television shows.

Glossary of its explicit dictionary meanings

Dictionary Meaning of 肉

According to the Chinese Classic Dictionary[3], 肉 can be used as a noun, adjective, and verb. As a noun, the most popular occasion using 肉, is when it comes the meaning of meat or flesh (both for animals and fruit). As an adjective, it can be used to describe people being lack sophistication or are superficial, or used to express the slow-motion of human beings. Another usage as an adjective is to express intimacy towards kids or lovers, for example, “肉肉的“, means chubby. As a verb, 肉 means eat meat, swallow, or flesh up.

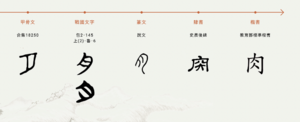

Historical Evolution of 肉

Chinese characters use logograms, which consist of the form characters instead of the letters of an alphabet. There are six types of Chinese characters: Pictograms, Phono-semantic characters, Simple ideograms, Loan characters, Transfer characters, and Compound ideograms. 肉 belongs to the category of Pictograms. The earliest written appearance of 肉 can be traced back to the Shang Dynasty, in which the character looks like meat being placed horizontally. The form of 肉 was transformed to vertical in the spring and autumn period. Finally, after the period of Chinese characters evolution/libian (隸變[4]), when 肉 is used as a radical, the character is similar to 月(moon) nowadays.

An elaboration of its variegated meanings, actual usages, and value-loaded implications

The multiple explicit meanings and implicit connections

肉 (rou) is commonly used in the sense of meat of animals and fruits, but it is also used as 小鮮肉 (Xiao Xian Rou) to mean the appearance of gender-neutral, young and handsome male in Chinese culture today. Luhan and Chris, who debuted as EXO from a Korean entertainment agency, and TFBOYS, which is China's first domestic boy idol group, are known as the icons that represent Xiao Xian Rou. They changed the ideal image of males among Chinese women, which is in contrast to the muscular, tough males who were considered the ideal male image during the Cultural Revolution.[5] The male celebrities defined as Xiao Xian Rou were able to become successful in many areas of Chinese media such as film, drama, and music, and the word of Xiao Xian Rou was used on the Internet by mainly the young generation to compliment their appearance.

Meteor Garden (流星花園) is a TV drama series that was broadcast in China in 2018 and was a remake of the Japanese drama (Hana yori dango) and its Taiwanese counterpart. The four male members in the story, known as the F4, share slim physiques, bright skin, and attractive faces with makeup in common. Hence, they were said to represent Xiao Xian Rou and have gained a lot of popularity mainly among the younger generation. When they appeared on the Chinese TV program called The First School Class that giving lectures to elementary school students, the effeminate taste of their Xiao Xian Rou caused a heated public debate as it was considered to have a negative impact on the next generation in China as a morbid culture and symbol.[2] Chinese state media ridiculed them as “niang pao” (娘炮 ) meaning sissy pants. [6] Hence, some people also call them niang pao in a negative sense.

Another meaning of 肉 is for both raw and cooked meat, originating in Japanese comics. Raw meat refers to Animation, Comic, Game and Novel (ACNG) works that do not contain subtitles, whereas cooked meat refers to works that do include subtitles, requiring translation. [7] This terminology is utilized in Chinese/British/American pop culture, and Korean dramas. [7] Raw meat, also known as raw files or media are uploaded for viewing much earlier than cooked files for viewers fluent in the language of production. [7] Cooked media must be translated before this label can be used, therefore these are seen circulating much later than their counterpart. [7]

Related terms associated with the xiao xian rou

老腊肉(lao lar rou)

This term is also used to describe the appearance of males and is mainly used to refer to middle-aged males. Culturally appropriated characteristics associated with white males in the mid- 20s century. 老腊肉 (lao lar rou) includes males who have cool, stylish, and men with adequate muscle. It doesn't include whitening skin and youth. [1] While the original meaning of 小鮮肉 (Xiao Xian Rou) is fresh, 老腊肉 (lao lar rou) means old and baked meat. As an old male, it is often used as an antonym of xiao xian rou in a negative sense.

娘炮 (niang pao)

The literal meaning is girl gun. This term is used for men who look as young and neutral in appearance as well as Xiao Xian Rou, but this term refers to more effeminate and weak males. Therefore, while Xiao Xian Rou is used to compliment males, 娘炮 (niang pao) tends to be used as a derogatory term. The term has recently gained international attention after China's National Radio and Television Administration (NRTA) began restricting the elimination of males who are like 娘炮 and 小鮮肉 in the entertainment industry by decrying this youth culture as a distorted sense of beauty. [8]

阳刚之气 (yang gang zhi qi)

The term is used to describe a man with an inner spirit of positivity, generosity, openness, strength, and masculinity. Chinese male idols are required to have the identity with 阳刚之气 (yang gang zhi qi) norm, and if they do not follow it, it is considered that their entertainment lives may be affected. [9]

Counterpart terms of Little Fresh Meat in different languages

South Korea’s “Flower Boy”

South Korea is one of the pioneers of implementing “Soft Masculinity” as a popular culture in males. Even Though South Korea started as a Patriarchal society, in which the ideal man has to be built, muscular, tough, and entrepreneurial, the trend has started to shift more towards a soft masculinity. Hence the term Flower Boy, or Kkonminam in Korean emerged.[10] Flower Boy or Kkonminam is a way to describe a male with a soft appearance, smooth skin, and decent manners while wearing fashionable clothes and makeup. The trend started to shift to the flower boy concept ever since the Korean boy band Seo Taeji and The Boys came into the scene. Starting a new culture incorporating rap, rock, and techno into their music. The increasing popularity of the group gave birth to more girl groups and boy groups which will later on bring K-pop to the international stage.[11] These Kpop boy groups usually embody the Flower boy soft masculine concept, having smooth skin, beautiful faces, and an overall soft masculine compared to the tough guy that was the norm in the 90s.[12] An example of “Flower Boy” can be seen by famous Korean actor Song Joong Ki in Descendants of the Sun.

Japan's Bishonen (beautiful boy)

Simillar to Little Fresh Meat, Bishonen, or translated into Beautiful boy in Japanese describes a young man of androgynous beauty. Bishonen is usually used by female anime lovers when referring to their favourite male anime characters. Bishonen should be used for boys under 20 as pretty man would be called biseinen. However, most people use Bishonen to refer to all ages. [13]

This term is usually used by non-Japanese anime lovers, especially Americans, to refer to a handsome male character. Often these characters are voiced by female voice actors. However, their strongest appeal is their Tsurime Eyes, these eyes are unique to Japanese anime and can easily captivate and increase the beauty of these characters. An example of these Bishonen can be found in the popular Japanese role playing game “Final Fantasy” with most of their main make characters having beautiful faces.[14]

English's 'Pretty boy'

In English, a similar meaning to Little Fresh meat is the word “pretty boy” which depicts a young teenage male with perfect hair, facial features, and skin. They are those who are always self conscious of their appearance through looking at the mirror every few seconds to fix their look. Whether to impress other people or to feel good about themselves, these pretty boys are often the stars of the show and easily noticeable by males and females. [15] Some example of “Pretty boy” can be seen through music artists such as Justin Bieber or Shawn Mendes.

Compare and summarize multiple meanings

Although in Mandarin, 肉 can be used as a verb, a noun, or an adjective which can be slightly different in contents. However, generally speaking, the most frequent scenarios that 肉 has taken part of is when people are describing 'meat' or 'flesh'. As we can see from the above illustrations, there are different yet similar terms that are used to describe the soft masculinity of the boys and men.And these meanings have been widely used cross different countries and cultures (for example, the kanji of meat in Japan is also 肉 which also means meat.)

Meanings that are transferred, distorted, or subverted

The dictionary meaning for 肉 (rou) has been transferred in one major way. The rise of feminine male appearances noted as “Little Fresh Meat” (Xiao Xian Rou) in Chinese popular culture has distorted 肉 (rou) to illustrate an idiosyncratic interaction between masculinity, Chineseness, and duty to the nation. [2] “Little Fresh Meat” (LFM) describes the expanding recognition of youthful male celebrities who express feminine characteristics and aesthetics, such as a narrow frame, cosmetically corrected bodies, and faces, long and voluminous hair, and feminine style fashion. [5]

There are two idioms associated with this masculinity descriptor, “Little Fresh Meat” (LFM) and “Old Grilled Meat” (OGM). [1] LFM’s innocence, youth, and vigor contrast OGM’s rough, mature, and developed attributes. [1] However, only LFM will be discussed in this article as the term was directly subverted from the keyword 肉 (rou).

Xiao Xian Rou gained popularity when female fans, along with other women began describing the male body as contemporary pieces of “meat” (rou), overflowing with faint undertones of male sexual objectification. [1] Because this term contains sexual implications, LFM is often used for the characterization of young, good-looking individuals. [1] Customarily, women’s bodies have been at the forefront of sexual objectification, but LFM diverges this tradition, becoming an attribute for implicit heterosexual lust after the male body from a female point-of-view. [1]

The hegemonic mechanism of masculinity, outlined through its state allegiance, and rejection of both queerness and femininity, creates a hierarchy among the public and the government. [2] LFM’s role as a gender norm comprises both the state’s obvious resentment towards effeminate men and the government’s greed for the development of the consumer market. [2] This fear of castration at the core of various state values revolves around the exclusion of effeminate men, dating back to the early 1980s Mao era when academics often became discontent with feminist ideologies searching for genuine men who could lead the nation. [2] LFM is often portrayed in a negative context to oppose the “male gaze”, interpreting men in this category as naïve, unskilled with regards to love and intimacy (“fresh”), while having an attractive, healthy body (“meat”). [2] This style is thought to reflect the international craze of “Pan East-Asian soft masculinity”, influenced by the Korean kkonminam (flower boy), as an alluring male with soft skin, hair, and a feminine demeanor and the Japanese aesthetic bishōnen (beautiful boy), often found in the BL/Yaoi subgenre of shōjo manga (girls’ comics), or in the idol industry and its corresponding fandom culture. [2] However, it is noteworthy to mention that LFM is rooted in traditional Chinese compassionate wen masculinity. [1] Wen masculinity describes individuals who are artistic, scholarly, and often reflective intellects. [1] Therefore, the term LFM is partially rooted in Chinese popular culture but better explored in Korean and Japanese popular culture.

The common admirers of this beauty standard are young, heterosexual women as they are no longer the subject of the “male gaze”, rather they can reverse traditional gender inequalities, creating their own “female gaze”. [2] With the rise of female empowerment and feminism, significant changes in China’s economic growth and female power now allow for recognition that both a woman’s and man’s appearance are elements of heterosexual desire. [2] Nevertheless, this development is still quite new in the field of gender politics, leaving women’s bodies as the dominant gender for objectification in patriarchal Chinese society. [2]

Social, cultural, and political problems

Due to the use of rou in Xiao Xian Rou (LFM) used as a term to discuss young, attractive men, the sexualization and sexual exploitation of celebrities, idols, and models became inevitable. China’s idol industry, influenced by Japan and South Korea’s J/K-Pop industry has developed dramatically in recent years with idol management teams choosing to recruit trainees that are younger. This easily allows for the exploitation and hyper sexualization of underaged idols, through schoolgirl/schoolboy characteristics, leading to increased instances of sexual violence in youth, and a lingering notion of pedophilia. [16]

Cultural problems

Various problematic opinions on LFM stem from cultural stereotypes in the PRC. Toxic masculinity has been prevalent since the beginning of time. The traditional Chinese idea that men should be athletic, tough, mature, and dominant, reinforces male hegemony and openly opposes gender equality. [17] Boys in China are commonly expected to perform well in math and science, be proficient in sports, and take on a position of leadership. [18] These gender norms stem from men being associated with the tougher, active, lighter 'yang' (陽), and women being associated with a passive, darker, and earthy 'yin' (陰). [17] In modern China scholars often state that 'yin' is in abundance, and 'yang' is in recession. [17] The concept of LFM puts a direct strain on this traditional belief, challenging male beauty to transition to a gender neutral, more effeminate form.

Political problems

One political problem associated with LFM is that a new Chinese proposal from the Ministry of Education details the 13th Five-year Plan period from 2016-2020 put forward to impede effeminization of adolescent males. [19] This proposal is aimed at young males who don’t conform to traditional Chinese male stereotypes. The legislation proposes to hire a greater number of physical education teachers, implement extensive fitness programs, and assist with research on the impact of celebrities on modern youth. [19] The ministry states that efforts to improve this issue are essential for national security, cautioning China that an increase in feminine qualities in male adolescents jeopardizes the endurance and advancement of China. [19] One advisor on the board even described how Chinese young men have been overindulged by housewives and teachers allowing for them to evolve into effeminate, weak, and impuissant men, and that something must be done. [19] Over 20,000 new fitness teachers were added into the Chinese education system in the last five years through complimentary teacher schooling. [19] Although the ministry is actively pushing for this transition, much of the public do not support this change and are constantly bringing awareness to these harmful male stereotypes. [20] The ministry recently acknowledged the masses to explain that their implementation of this program does not reflect masculinity or male attitudes, rather it is provided to increase adolescents’ physical activity levels, develop healthy habits, and maintain a tough attitude. [19]

Social Problems

Socially, netizens have become anxious over the state’s deep-rooted toxic masculinity and share their opinions and viewpoints on social platforms, begging the public to abandon gender stereotypes. [21] Chinese consumers are even holding various companies liable for actions that shame effeminate men. [20] However, the state is also fighting the masses as future legislation is being discussed around the PRC that will create further boundaries for androgynous men in the advertising, fashion, or beauty industry. [21] The state has even implemented various media censors, for example in 2019 when they cut scenes of homosexuality in the American film “Bohemian Rhapsody”, or when they blurred earrings on multiple male celebrities that came onto Chinese TV shows. [22] Another regulation ordered the broadcasters by the authority to resist “abnormal aesthetics” such as “sissy” men, “vulgar influencers”, and performers with “lapsed morals”. [23] Many scholars propose that these actions were due to an internalized, nationwide homophobia, passed down from ancient Chinese beliefs. [20] This topic will not be discussed in detail on this WIKI, however, in summary, LGBTQ+ rights are extremely suppressed in the modern PRC, with same-sex marriage still being illegal, due to a national, state-induced fear of male castration.

Influenced by Confucianism and South Korean pop culture, Chinese youth have been adopting the LFM, effeminate look, directly contrasting the traditional OFM look that was often seen in Chinese media. [2] This rise in more feminized males could be due to the rise of feminism, and fight for gender equality. But there are also netizens choosing to criticize LFM, often describing LFM as being a bad influence to the younger generation, and delivering the concepts of becoming “feminine” as a normal and right gesture. This draws the authority's attention to reform this society's “unhealthy” tendency. To sum up, the issues related to LFM do not only affect a cultural dimension but rather a phenomenon that further influences the state policy and society's points of view. Another trend that might be interesting to explore is how LFM transpired with respect to China’s one-child policy from 1979-2015. [24] With the blunt gender disproportion with nearly 37 million more males than females, how will the LFM affect society in the future?

Influence of Xiao Xian Rou on Changes in the criterion for the beauty among younger males in China

The rise of male celebrities called Xiao Xian Rou has had a psychological impact on the criterion for the beauty of not only Chinese females but also males, and younger males increasingly imitating their faces through makeup and plastic surgery. This has led to the rapid growth of the Chinese cosmetic surgery market in association with improvement in living standards. According to SoYoung, one of the popular cosmetic surgery-specific apps, 14 million Chinese went through cosmetic surgery, accounting for about 41% of the global total. 96% of patients under the age of 35 undergo cosmetic surgery in China, indicating that younger generations tend to have the surgery compared to the United States, where 75% of patients are over the age of 35. [5] Also, about 17% of Chinese males have received cosmetic medical treatment, and younger males are increasingly undergoing the surgery. [6] The trends in Chinese males’ cosmetic surgery are characterized by the face of actor Yang Yang, a small mouth like pop idol Luhan , and large double eyes like Huo Jianhua, they are said to be representative figures of Xiao Xian Rou. [5] While males with square faces that combine a strong, muscular image used to be considered attractive, there has been an increase in the number of males who try to alter into oval contours that combine feminine images. [5] Moreover, according to a survey conducted jointly by China's CBN DATA and cosmetics brand Clinique, 91% of the subject of the survey, males answered that they would like to try skincare for whitening, and the need for whitening in China is becoming more gender-free. [25] Therefore, it is clear that Xiao Xian Rou has a significant influence on the change in the criterion for the beauty of younger males in China, with those criterions approaching more feminine. The reason behind the emphasis on appearance among men as well is related to the lookism that spreads in East Asia. [26] In China, job applicants are generally required to submit a photograph, and it is believed that a good appearance is a key to social success not only for women but also for males. [27]

Film Study of Meteor Garden demonstrating the development of "Little Fresh Meat"

In Geng Song’s study about Little Fresh Meat, he discussed the hit Chinese television show “Meteor Garden” and how it changed Male beauty. Meteor Garden (Liuxing Huayuan) is an adaptation of the Japanese Manga Boys Over Flowers (Hana yori dango). The story centers around a campus love story between a girl from an ordinary family and the son of a wealthy family. This series has been adapted in different countries such as Taiwan, Mainland China, Korea, Indonesia, India, and Thailand. We will focus on the Mainland Chinese adaptation Meteor Garden (2018) starring Dylan Wang, Guan Hong, Connor Leung, Caesar Wu, and Shen Yue. In every Meteor Garden adaptations, the F4 gang is usually associated with the term “Little Fresh meat” or referred to as “Pan-East Asianness” as the four man in the gang F4 always involves Asian actors with androgynous beauty such as smooth skin, fashionable, trim physique, and attractive facial features. The goal of highlighting these male beauties as members of F4 is to appeal to young females, similar to the scene in the series where F4 is often worshiped like stars by the school’s girls.[2] Thus, Meteor garden is a popular youth drama idol that features a new style of male beauty that focuses on transnational flow of images, a commercial drive, and primarily targeting heterosexual young female fans. However, it must also be noted that the show did little to address traditional gender binaries and inequalities.[28]

Conclusion

肉 (rou), a term historically resembling meat, has evolved into Xiao Xian Rou, commonly used to represent effeminate, young males, arising from South Korea’s ‘flower boy’ (kkonminam), Japan’s ‘beautiful boy’ (bishōnen), or North America’s ‘pretty boy’. [2] Rou can represent a lack of sophistication, be used as a term of intimacy between children or partners, or to represent translated, and subtitled/non-subtitled works. Often, Xiao Xian Rou (Little Fresh Meat) has become subverted in a negative context to symbolize 'yin' and sexualize young Asian celebrities, especially when used in the J/K/Mando-Pop industry. [16] In China however, Xiao Xian Rou is often used as a derogatory term for androgynous feminized men, promoting toxic masculinity, homophobia, and gender inequality. This raises political issues in China because the state often aligns with traditional values of toxic masculinity. The ministry of the PRC has even recently proposed legislature that attacks Little Fresh Meat (LFM) males, forcing these youth to adapt to the traditional Chinese male characteristics (strong, intellectual, athletic). [19]

The Chinese television show “Meteor Garden” was discussed as it consisted of a popular quartet of males (F4) that resembled the LFM archetype. The success of this show skyrocketed with heterosexual female fans romanticizing these protagonists and the effeminate male look. Companies began including effeminate males in beauty, fashion, and fragrance advertisements, and Chinese celebrities began using cosmetics and plastic surgery to enhance their features. [5] The topic of LFM’s relationship to queerness, and an ancient nationwide homophobia in the PRC were briefly introduced. Further study and discussion are needed on this complex topic, specifically in terms of the LGBTQ+ movement in the PRC, and its relationship to both the one-child policy and Xiao Xian Rou.

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Jiang, Jiani Bruce; Huhmann, Bruce A; Hyman, Michael R (2020, 2019). "Emerging masculinities in chinese luxury social media marketing. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics". Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics. vol. 32, no. 3,: pp. 721-745. Check date values in:

|date=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: extra text (link) - ↑ Jump up to: 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 Song, Geng (May, 2021). "Little fresh meat": The politics of sissiness and sissyphobia in contemporary china. Men and Masculinities". SAGE journals. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "肉的基本解释". 漢典. Retrieved Mar, 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "肉 (汉语汉字)". 百度百科. Retrieved Mar, 2022. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Wen, Hua (Apr, 2021). "Gentle Yet Manly: Xiao Xian Rou, Male Cosmetic Surgery and Neoliberal Consumer Culture in China". Asian Studies Review. 45 no. 2: 253–271. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Lauren, Teixeira (Nov, 2018). "China's Pop Idols Are Too Soft for the Party". FP INSIDER. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 N/A (March, 16, 2022). "What is raw meat and cooked meat?". Sheng huo xiao zhi shi (生活小知识). Retrieved March 19, 2022. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Boreham, Andy (Oct, 2021). "Niangpao directive all good and well, but what about naturally 'sissy' men?". SHEINE. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Weiner, Jesse; Li, Weiyu (2021). "China Trying to Eradicate "Sissy Boys" and "Overly Entertaining" TV and Media Programs". YK LAW.

- ↑ Baruah, Rupshikha (16 September 2021). "The Flower Boy Trend of South Korea: Changing Language of Masculinity". doingsociolog.org. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- ↑ "Flowerboys and the appeal of soft masculinity in South Korea". bbc. 5 September 2018. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- ↑ Jung, Sun (2010). "Chogukjeok pan-East Asian soft masculinity: Reading Boys over Flowers, Coffee Prince and Shinhwa fan fiction". In Black, Daniel; Epstein, Stephen; Tokita, Alison (eds.). Complicated Currents: Media Flows, Soft Power and East Asia. Melbourne: Monash University ePress. pp. 8.1–8.16. Archived from the original on 25 May 2020. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ↑ "bishounen". Urban Dictionary. 1 July 2003.

- ↑ "Bishonen". Tropedia Fandom. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- ↑ "Pretty Boy". Tropedia Fandom. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- ↑ Jump up to: 16.0 16.1 Olfman, Sharna (2009). The Sexualization of Childhood. Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers. p. 57. ISBN 9780275999858.

- ↑ Jump up to: 17.0 17.1 17.2 Fang, Tony (2015). "Yin Yang: A New Perspective on Culture". Management and Organization Review. 8(1): 25–50.

- ↑ Choi, S.Y.P; Li, S (2020). "Migration, service work, and masculinity in the global South: private security guards in post-socialist China". Gender, Work & Organization. 28(2): 641–655.

- ↑ Jump up to: 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 19.5 19.6 Ministry of Education of the PRC (2020). "Letter on the reply to proposal no.4404 (education 410) of the third session of the 13th national committee of the Chinese People's political consultative conference". Ministry of the PRC. Retrieved March 15, 2022.

- ↑ Jump up to: 20.0 20.1 20.2 Williams, G.A. (2021). "Is China Killing off its "Little Fresh Meat"?". Jing Daily. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ↑ Jump up to: 21.0 21.1 Chan, A (2021). "China proposes teaching masculinity to boys as state is alarmed by changing gender roles". NBC News. Retrieved March 15, 2022.

- ↑ Reuters, A (2019). "China's censors drop gay scenes from 'Bohemian Rhapsody' film". NBC News. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ↑ Vincent, Ni (Sep, 2021). "China bans reality talent shows to curb behaviours of 'idol' fandoms". Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Potts, M (2006). "China's one child policy". BMJ. 333(7564): 361–362.

- ↑ Morishita, Satoshi (May, 2021). "Dentouteki na bihada kankaku ga nokoru Chuugoku de motome rareru hada to ha". The Shukan Syogyo. (What kind of skin is required in China, where traditional aesthetic sensibilities remain?) [published in Japanese]. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Wong, Lindsay (Oct, 2021). "Asian Beauty Standards and it's Negative Consequences". WORK IN PROGRESS magazine. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Yip, Waiyee (july, 2021). "Plastic surgery booming in China despite the dangers". BBC NEWS. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Harvey, S . 2019. “‘Sissies Weaken the Nation’: Mapping the Discourse Surrounding Niangpao and Reading Gender Performance in the TV Drama Sweet Combat.” MA thesis, Shanghai Theatre Academy.

| This resource was created by Course:ASIA319. |