Course:ASIA319/2020/"Masochism" (虐)

Introduction

Masochism in Chinese is written as 虐 (nüè), and is used to describe the act and feeling pleasure from cruelty, violence, pain, and disasters.[1] The word masochism in Chinese culture has several representations that have been widely developed in literature styles, idiom allusion, and psychological descriptions. Despite its original set of meanings, masochism, during China's rapid modernization, has expanded, in combination with additional characters, to host a variety of new meanings and implications. The word masochism is influential by it's wide adoption in major developing countries around the world, affecting languages such as Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese. However, due to the generational gap and cultural differences, masochism with the character 虐 have created misunderstandings and misuses in Chinese popular culture. For example, the meaning of masochism in English is mainly used to describe sexual pleasures gained through pain; however, the original Chinese meaning of 虐 centralizes the asexual aspects of pain. In the contemporary context 虐 is not always tied with sexual connotations, and this can be seen through the wide adaption of masochism popular culture (受虐文化: shòu nüè wén huà) in literature and television programs.[1] In particular, it was found that females are the main consumer of these masochistic commodities; which involve eating extremely spicy food, enduring intense workout routines, and consuming tragedy masochistic novels. The vibrant Chinese popular culture that the effects of masochism are go beyond entertainment but extends towards existing social, cultural, and political problems in China.

The Genesis of 虐

"虐" (Masochism) has been used in the Chinese language for centuries to describe physical acts of torture, abuse, and violence. However, overtime the application and meaning of "虐" (Masochism) has evolved from one of extreme violence, to the referral of anything that causes mental or physical pain. The origins of this usage can be linked to the emergence of Chinese web novels in the early 2000's[2], where masochism is prominent in the genre of Tragedy Romance (虐恋小说: nüè liàn xiǎo shuō). Tragedy Romance literature tells the stories of star-crossed lovers who are involved in melodramatic romantic relationships involving betrayal, revenge and misunderstandings.

Writers and readers categorize such novels as masochistic due to the pain directed at both the characters and the reader. The fictional character suffers from both physical and mental violence, abuse, death of loved ones, car accidents, disabilities, infidelities, and manipulation. In contrast, the reader suffers the emotional pain of reading such tragedies.[3]

While the enjoyment of Tragedy Romance and sadistic love stories have only become popular in the past decade, Tragedy Romance literature can be traced back centuries. A notable example is the Dream of the Red Chamber (红楼梦 hóng lóu mèng), one of China’s Four Great Classic Novels written in the Qing Dynasty.[4] From ancient literature to recent popularized web-fictions, the development of Tragedy Romance novels has given rise to a contemporary masochistic culture (虐心文化: nüè xīn wén huà) in China. These texts act as roots for contemporary masochistic commodities including video games, TV dramas, and movies which further influence the Chinese culture and societal structure today.[5]

Dictionary Histories and Definition

Dictionary Meaning of 虐

The structure of 虐 is defined as a semi-enclosed structure; the top of the character is seen as the head of a tiger (虍) and the bottom part meaning death. In Chinese Classic Dictionary[6], it is used as an adjective, noun, and verb. As an adjective, 虐 can be used to describe someone who is abusive. As a verb, 虐 is used to describe abusive actions. As a noun, 虐 can be translated to ill-treatment, violence, and exploitation. Commonly, people use 虐 to demonstrate meanings of abusive and cruel; however, 虐 is also interchangeable with 谑 (xuè), which means to make fun of someone verbally.[7]

Historical Evolution of 虐

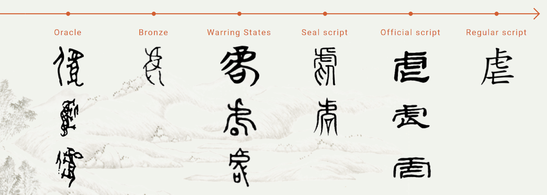

Before the formation of scripts, ancient China relied on pictographs as a form of written communication. 虐 was originally designed to depict pain and cruelty, it's character was shaped as a tiger slashing at a human with its claws.[8] The earliest written appearance of 虐 can be traced back to the Shang Dynasty’s oracle bone script which is considered one of the oldest forms of Chinese writing.[9] This character's development is evident of what characterized the Shang Dynasty; overwhelming violence, brutal political leaders, sacrificial rituals, warfare, and human hunts.[10] Scholars throughout history had consistently used the character 虐 along with other words and idioms to describe the violent culture and emperors who served during this time. For example, the idiom 助纣为虐 (zhù zhòu wéi nüè) was used to describe the aiding tyrants in their abusive acts.[11] Overtime, the character was simplified by removing some visual elements of the tiger, claw, and human, which forms the regular script version of 虐 (nüè) today.[12]

Words Associated with 虐

Basic Terms

- 虐刑 (nüè xíng) / 虐行 (nüè xíng) — Noun. torture / abusive action

虐刑 is defined as cruel punishment. 虐行 is defined as atrocious behaviors. These two words have the same pronunciation but different meanings. Both were originated from ancient Chinese language. 虐刑 firstly appeared in an historical classics: The Spring and Autumn Annals of Yan Zi, "If there is no resentment in the people and no abuse in the country, any problems can be dealt with".[13] These two terms are still used nowadays to describe issues related to domestic violence, child abuse, family violence and other unethical behaviors.[14]

Contemporary Slang

- 虐恋 (nüè liàn) / 虐心 (nüè xīn) — Noun: sadistic love / torturing heart

These two terms are developed from Chinese literature and Chinese popular culture.[3] These two terms are popular amongst females, predominantly teenagers.[15] Chinese leisure companies such as have created a huge amount of films and TV series of sadistic love content to attract more consumers.Currently, sadistic love and torturing-heart dramas and literary novels are favored in China. Young females are attracted by the reversal plots in the contents because they experience a "love addiction" through the sadistic love dramas, not only satisfy their psychological expectations but also not afraid of being hurt by a real romance.[16] However, there is a slight difference between these two words in separate usage. 虐恋 can be used to describe the sexual pleasure gained by physical pains. While, 虐心 is used to express inner feelings. Over the past decade, China's youth enjoy searching torturing heart media and novels to read as it expresses and reflects their own inner turmoil.[17]

- 互虐 (hù nüè) — Verb: mutual abuse

互虐 is a relatively new term derived from 虐恋 and 虐心. The term is applied on couples who harms each other mentally through disloyalty, suspicions, and arguments.[18] The term is also sometimes used in Tragedy Romance drama to refer to a couple who loves each other deeply but can't help to hurt each other either intentionally or unintentionally. The most frequent situation of using 互虐 is in a romantic relationship both in reality and some online romantic novels.

- 甜宠 (tián chǒng) / 甜虐 (tián nüè) — Noun: sweet love / bitter-sweet love

甜宠 is a term that is opposite of masochism and is used to describe sweet romance. The term 甜宠 is developed from Chinese web literature as a genre completely devoid of masochism and heart breaking elements. The plot usually features a male character who offers unconditional love and protection to his lover who is also sweet, cute, and loving.[19] Critiques have patronized the 甜宠 genre and called it unrealistic and boring due to it's lack of drama, hardships, and climax in the plot.[20] In contrast, the genre 甜虐, which translates to sweet abuse, is more popular than 甜宠 because it contains both the sweet and bitter aspects of romance. While the plot might be melodramatic, the readers find 甜虐 as more passionate and memorable because they were able to build a strong emotional connection to the characters. A classic example of a 甜虐 work is Qiong Yao's Romance in the Rain that demonstrate both sweet love and bitter romance between the main characters.[21]

- 虐狗 (nüè gǒu) — Noun/Verb: to show affection in front of single people

The term 虐狗 originally means torturing dogs. However, the term has become an internet slang, meaning couples showing public displays of affection in front of singles. The origin of the term 虐狗 derives from another popular internet slang, 单身狗 (dān shēn gǒu), which is used as a self-mockery for single people to describe themselves. Instead of expressing actual torture and psychological harms, 虐狗 is a way for single people to express their admiration and blessing to the couple's relationship.[22]

虐 in Chinese Popular Culture: Multiple Meanings and Implications

虐 in Everyday Conversations, Discussion Forums, Popular Press, and Television

Masochism in everyday conversations has two main connotations; the first alludes to a serious violent situation while the other is used jokingly to describe a sense of pleasure from pain. The first usage of masochism is commonly used in popular press, media, and colloquial conversations to describe the action of abuse and various types of mistreatments such as animal abuse[23], sexual abuse[24], and child abuse.[14] The second employment of masochism is used to describe the enjoyment of an activity that is mentally or physically straining; examples include: doing a painful workout routine, eating spicy food, and watching sad TV dramas. A recent term adopted by the media is "虐腹 (nüè fù)", which directly translates as torturing one's stomach. The term has similar connotation to words such as "brutal" and "intense" that are used by fitness influences to describe painful workout routines for the abdominal muscles.

In addition to workout routines, the most common discussions of masochism is under the terms of Tragedy Romance and sadomasochism (虐恋) literature that involves a melodramatic plot where the characters undergo through misfortunes such as heartbreak, misunderstanding, abortion, amnesia, and suicide. Famous Chinese Tragedy Romance dramas are then adapted from these web novels such as Goodbye My Princess (東宮), The Journey of Flower (花千骨), Eternal Love (三生三世十里桃花) , and Scarlet Heart (步步惊心).[25] While television dramas all have different plot lines, the characters all suffer similar emotional turbulence in their romantic journey.

Counterparts of Masochism in Non-Mandarin Languages

Language Counterparts Using the Same Character:

- Japanese Kanji: 虐 /ギャク / しいた.げる (gyaku / shiitageru sokonau)[26]

- Meaning: oppress, tyrannize, persecute[27]

- Related words:

- 残虐な (Zangyakuna) - cruel, brutal

- 虐杀 (Gyakusatsu) - slaughter, massacre

- Korean Hanja: 虐 / 학대 (hakdae)[26]

- Meaning: abuse, mistreatment

- Related words:

- 학대하다 (hakdaehada) - to tyrannize, to mistreat

- Vietnamese Chữ Nôm: 虐 / ngược[26]

- Meaning: reverse, contrary, inverse[28]

- Related words:

- ngược đãi - persecute, batter, mistreat, punish

Comparison of Words and Uses in Popular Culture Other Languages

While 虐's meaning in China has changed with the passing of time, the usage in some countries has retained more of it's original meaning. In China, 虐 has a contemporary use for explaining physical or mental pain and has been adopted into use in popular culture through tragic love stories or physical pain from workouts. On the other hand, the Japanese and Korean uses of 虐 have stayed close to their original historical usages. The Japanese and Korean usage is close to the historical uses of 虐 in China, with meanings of oppression, abuse, or mistreatment. These terms have not been adopted into popular cultural uses, with the term retaining it's meaning of literal abuse and violence rather than lighter uses. In Japanese, 虐 can be used to closer to the English translation of masochism, meaning sexual pleasure induced by pain. Korean, however, does not use 虐 in the sexual connotation.

The Vietnamese 虐 (ngược) has the most removed definition from the others, but it is used most similarly to China's 虐 in popular culture. Vietnamese uses the term to mean opposite or inverse, with additional words needed to mean abuse or mistreatment. However, the word is often used as a genre of Vietnamese visual novels which contain "paradoxical love" or "opposite men".[29] This literature category is called ngược and is characterized by one person who must endure mental (inverse of mind) or physical (inverse of body) pain. These types of novels use the idea of ngược nam (opposite man) who are often mentally or physically abusive, and have the girl go through difficult situations throughout the novel.

While the word 虐 has failed to match the growth across cultures with the Chinese counterpart into popular culture, there are similar words and popular culture phenomenon's in other cultures that match the contemporary use of 虐 in China.

In Korea, the subject of "비련" (sad love) is a common subject of literature, dramas, movies, and songs. Similar to the Tragedy Romance genre in China, the stories revolve around love stories in which the characters suffer misfortunes, or fail to maintain their relationship due to factors outside their control. Examples of popular culture in this genre are Jae-Seok Shim's 1983 movie “Tragic Love" and Yoo Chul Yong's "Sad Love Story".

Distortion of Dictionary Meanings

Although the character 虐 retains its original definition of abuse or tyranny in everyday use, the character has been appropriated into pop culture in such a way that distorts the meaning. The use of the term when describing the voluntary consumption of spicy food, difficult workouts, or sad media subverts many aspects of the historical definition of 虐. By adopting the term into conversations about voluntarily subjecting oneself to pain, it changes the original thought of abuse or cruelty from being outwardly subjected to a voluntary activity. It also changes the idea of abuse from an unbearable tragedy to a self serving pleasure.

The character 虐 is often translated into English as masochism, stemming from modern implications of pleasurable pain. However, in English, the word masochism has an implication of sexual meaning, most often referring to sexual pleasure derived from pain. For this reason, the meaning of 虐 can be misunderstood when translated to English, as the Chinese word does not necessarily carry the same connotation. This is especially evident in the categorization of the Chinese Tragedy Romance genre as sadomasochism or sadistic love genres when translated into English. This type of Chinese literature, under the contemporary context, is not confined to the sexual implications that the English categorization may imply.

Social, Cultural, and Political Implications

Masochism in the Everyday Social Reality

The popularity of masochism in Chinese popular culture is symptomatic of both the rapid change and the dilemma of clashing values in post-socialist China. The societal transition towards economic reform and opening-up policies has greatly influenced the identity of Chinese youth to be deep-rooted in consumerism and individualism.[17] However, China still greatly upholds its traditional collective ideology, leaving China’s youth at a crossroad between self-sacrifice and self-fulfillment.

Masochist fictions reflect the psychological pain, anxieties, and emotional suffering of living in a rapidly-changing society that is both entrenched in socialist tradition and promotive of neoliberal individualism. Chinese youth are able to relate to fictions that are turbulent and heart-abusing because they reflect the very unstable and converging social realities in which they find themselves situated.[30] Chinese youth gain a sense of pleasure from consuming masochistic narratives because they find solace in the realistic depiction of their own painful social realities.

Masochism as Therapy

The Chinese youth also engage with masochistic narratives because they find it therapeutic as it enables them to release their repressed emotions. China’s cultural identity is deeply rooted in Confucian ethics of emotional chastity, emphasizing on control of one’s emotions in pursuit of harmony. For over 3000 years, China has traditionally considered emotion and reason as co-existing and not separate and independent of one another.[31] China’s youth grew up in a society where they can not express emotions that are not controlled. Rather, emotional restraint is practiced and a great deal of emphasis is placed on controlling one’s emotions in accordance with Chinese aesthetic traditions.[32]

However, growing up in a neoliberal consumerist culture, Chinese youth seek to consume fictions that allow them to freely connect to their personal and emotional sensitivities. The excessive dramatization of emotion and painful tragedy in the masochistic fictions act as a cathartic experience for China’s emotionally suppressed youth.[30] Masochistic fiction becomes a realm in which they may enter to consciously dramatize and release their suppressed emotions, finding pleasure in the relief from their emotionally-suppressive society.

Masochism and the Female Audience

Women make up the majority of the audience of masochist fictions. This is because masochist fictions often follow a romantic narrative that women identify with and seek after for themselves. Female characters in these masochistic narratives surrender themselves abjectly in the name of love to a powerful, abusive male figure, offering themselves completely to their tormentors. This can be exemplified in domineering CEO novels (霸道总裁小说: bà dào zǒng cái xiǎo shuō). Both the female character and female audience are enduring this abuse from the male because they associate suffering with passionate desire and un-relentless love.[33]

Such an abusive understanding of love and romantic relationship is symptomatic of a consumerist culture that remains deeply patriarchal. The commercialization and commodification of the female body objectifies women and makes them as disposable as any other product in consumer society.[34] Their unstable position in society makes them desire a man that will obsessively love them to the point of abuse so that it will provide them with a sense of security that they will not be replaced by another woman. In other words, Masochism becomes a way for women to navigate their inner desire to find the security of being accepted unconditionally by their male counterpart. Women are greatly moved by the intense abuse inflicted on the female lead by the male lead because they associate deep abuse as the expression of true love.[35] Stories that entail dangerously obsessive, passionate, and heart-abusing love to the point masochism, provides women with a fantasy of stability within a consumerist society that will inevitably deem them replaceable.

Aesthetics of Masochism

In “Iris Murdoch’s Aesthetics of Masochism” by Bran Nicol, masochism is studied as an aesthetic form of production that reflects the truth of the world’s reality, driven by personal emotional energy. The journal highlights Sigmund Freud and Leo Bersani’s study on masochism and their considerations on how masochism impacts upon aesthetic production. Freud and Bersani regards masochism as not only primary in determining sexuality and subjectivity but also foundational towards cultural production. Aesthetics and cultural productions such as popular culture can be seen as a perpetuation and elaboration of masochistic sexual tensions.[36] These sexual tensions are not sexual in nature, but rather is an allegory for our conceptualized inner desires. The journal also presents Iris Murdoch’s notion of masochism. Murdoch suggests that when masochism is removed from a purely sexual context and sublimated into morality or art, it can be seen to be secretly driven by egotism.[36] By understanding masochism in it’s aesthetic form of production, it can be realized that popular culture narratives of masochism are able to mirror the conflictual social realities of the world through the lived realities and dreams of the individual. In other words, it is the collective of individual's social realities of emotion (as aforementioned above in cases as pain and unexpressed emotional turmoil) that upholds and shapes masochistic popular culture narratives, making it continuously relevant and influential.

The Problem of Masochism's Gendered Discourse

In chapter 4, Loving Women: Masochism, Fantasy and the Idealization of the Mother, of Rey Chow's book on "Woman and Chinese Modernity", Chow discusses the analytical prominence of women in modern masochistic Chinese literature and culture as symptomatic of China's deep-rooted patriarchal nationalist discourse.[37] Chow argues that the structure of masochism in which women are idealized stems from the major cultural demand of women to be self-sacrificing and remain in a constant sympathetic spectator position. Chow argues that because feminine self-sacrifice plays a major role in upholding traditional Chinese culture, it is inevitable that during China's collapse of tradition and modern social transformation, women are used as a substitute for China's traumatized self-consciousness .[37] Rather than progressing forward under their own terms, the modern Chinese woman is positioned by the state to support the patriarchal narrative of China's nation building. In reaction to such control of their identities, women engage in masochist literature and culture because it gives them agency in knowing that they are inflicting this abuse and pain onto themselves for their own means. In other words, they are reclaiming masochism by subjugating themselves to it willingly through the consumption of Tragedy Romance and other masochistic popular culture narratives. The consumption of masochistic literature and participation in masochistic culture becomes a safe and apolitical way for women to stand up against their state's desire for them to remain self-sacrificing towards men and their acts of nation-building. However, the consumption of masochism in Chinese popular culture does not give women the necessary agency to discuss and address the issues of their gendered role in society. Rather, the modern woman will be perpetually trapped within the pleasurable realms of masochism, painfully consuming away their unrealized needs and desires.

Conclusion

Masochism in popular culture has been greatly influential in the lives of modern Chinese citizens, evident by the large-scale consumption of masochistic culture and narratives in everyday dialogue, actions, and fictions. Despite its original usage of violence, pain, and cruelty under traditional Chinese literature, the term 虐 has now adopted a new set of meanings that reflects China's internal struggles of modernization. Masochism is used by modern Chinese citizens as a way to cope with the rapidly changing times of post-socialist China, by regulating suppressed emotions and providing consumers with a sense of control over their own lives. Although masochistic narratives and culture emerged from the social realities of China’s modern citizens, it serves as a form of social agenda by desensitizing people to tragedy and normalizing abusive behavior, perpetuating social inequalities and disillusionment. Thus, masochism remains a key identifier in understanding modern China’s problematic socio-cultural ideologies, making it an important topic for scholars and researchers to conduct future studies on.

References

- ↑ "Chinese Classics Dictionary".

- ↑ Feng, Jin (Fall 2009). ""Addicted to beauty": Consuming and producing web-based chinese "danmei" fiction at jinjiang". Modern Chinese Literature and Culture. 21: 1–41 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "虐心是什么意思?虐心文、虐心剧、虐心文化使人引起共鸣而痛苦不已". 2020-04-27. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- ↑ HSIA, C. T. (Summer 1963). "Love and Compassion in "Dream of the Red Chamber"". Criticism. 5: 261–271 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ "曾經捲走我們太多淚,經典八大虐劇你看過僟部?".

- ↑ "Chinese Classics Dictionary".

- ↑ "谑".

- ↑ "虐象形文字". 國學大師. Retrieved 2020-11-15.

- ↑ Major, John S (Fall 2002). "The Ancestral Landscape: Time, Space and Community in Late Shang China (ca. 1200-1045 BC)". China Review International. 9: 460+ – via Gale Literature Resource Center.

- ↑ Campell, Roderick (2018). Violence, Kinship and the Early Chinese State, The Shang and their World. Online: Cambridge University Press. pp. 178–211. ISBN 9781108178563.

- ↑ "助紂為虐". 教育部重編國語辭典修訂本.

- ↑ "虐".

- ↑ "虐刑".

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 蔡, 依庭 (2018-05-24). "虐童案例不只肉圓爸和17歲小媽媽! 3分鐘看台灣兒虐問題有多嚴重?". Business Today. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- ↑ "为什么很多年轻女性喜欢看虐文?". 2018-07-20. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- ↑ 王, 硕; 方, 健. "虐心剧 小虐怡情大虐伤身". 科学新生活: 8–9 – via 中国知网.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Wen, Huike (2020). Romance in Post-Socialist Chinese Television. Springer International Publishing AG. pp. 15–16.

- ↑ "喜歡互虐的星座組合,打打鬧鬧都是愛!". kknews. 2018-09-30. Retrieved 2020-11-15.

- ↑ "傻傻分不清的甜寵劇or瑪麗蘇劇,"甜寵+"將走向何方?". ptt news. 2019-01-28. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- ↑ "鋪天蓋地的甜寵劇裏,沒有愛情". sina.com. 2020-10-23. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- ↑ "甜虐是什么意思". 经典语录大全. 2018-12-08. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- ↑ ""虐狗"英语怎么说?和dog一点关系都没有!". zhihu.com. 2020-01-03. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- ↑ 蔡, 彰盛 (2020-02-10). "亂養狗被防虐動物協會送養 他竟罵人家是畜生". Liberty Times Net. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- ↑ 车, 东哲 (2007-02-05). "女白领口述:不堪忍受性虐待 雇人杀了变态老公". Souhu.com.

- ↑ "曾經捲走我們太多淚 經典八大虐劇你看過幾部?". 2020-02-17. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 "虐 Masochism". MDBG Chinese Dictionary. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- ↑ "Kanji:虐". Jitenon. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- ↑ "Ngược In English". Glosbe. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- ↑ "Truyennhieu". Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 "喜欢看虐文的人都是什么样的心态?为什么他们越看越high?".

- ↑ Barbalet, Jack; Qi, Xiaoying (2013). "The Paradox of Power: Conceptions of Power and the Relations of Reason and Emotion in European and Chinese Culture". Journal of Political Power. 6: 408.

- ↑ Chow, Rey (1991). Woman and Chinese modernity: the politics of reading between West and East. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. p. 121.

- ↑ Nicol, Bran. "Iris Murdoch's Aesthetics of Masochism". Journal of Modern Literature. 29: 154.

- ↑ Quan, Hong (2019). "The Representation and/or Repression of Chinese Women: From a Socialist Aesthetics to Commodity Fetish". Neohelicon (Budapest). 46: 717–737.

- ↑ "我们为什么相爱又相杀?". Retrieved 10 Nov 2020.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Nicol, Bran (2006). "Iris Murdoch's Aesthetics of Masochism". Journal of Modern Literature. 29: 148–165 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Chow, Rey (1991). Loving Women: Masochism, Fantasy, and the Idealization of the Mother. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press. p. 50.

| This resource was created by the UBC Wiki Community. |