Course:ASIA319/2020/"Greasy" (油)

Introduction

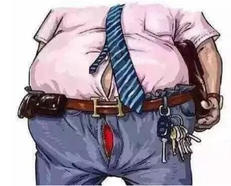

In 2017, the terms "greasy" and "greasiness" started to become a popular internet slang on Chinese social media. The People’s Daily listed it as one of the top 10 most frequently used internet slangs of the year[1]. While traditionally, a term used mainly in cuisine to describe various types of cooking oils or cooking methods like frying (油炸), the reason the term started to gain traction was when it started being used to describe middle-aged men in China who are deemed as rude, lazy, or out-of-shape by social standards[1]. It is considered a comedic insult directed at those who do not practice self-care or set aside time to develop a meaningful personal life[1].

Author and translator Feng Tang (冯唐), although not the first person to apply the term in this specific context, is credited with being the individual who popularized it, after having published an essay online in October 2017 entitled "How to Avoid Becoming a Greasy, Dirty Middle-Aged Man," (如何避免成为一个油腻的中年猥琐男) which has generated more than 9.2 million views[2] on Sina Weibo alone. It is worthwhile to study this keyword because beyond the obvious stereotyping and labeling of this term, further examination provides insight into various social, cultural, and political problems of contemporary China, including but not limited to class division, gender inequality, and workplace discrimination.

The Genesis of Greasy (油)

The term “oily” or “油腻” first appeared on Sina Weibo, a widely used microblogging platform similar to Twitter of the west[1]. However, Chinese netizens think that Feng Tang (冯唐) was the individual who ultimately gave fame to the term, as he was the one who assigned attributes and characteristics to the "greasy man” in an article titled “How to Avoid Becoming a Greasy, Dirty Middle-Aged Man”[3].

In this article, Feng called out those in current day society who are academically lazy, overweight, fail to maintain personal hygiene, talk about sex in public, and disrespectful towards the younger generations. He ultimately framed those who carries a number of these traits as a "greasy, dirty man"[3].

Besides Feng, many feminists in Chinese public have been shaming such behaviours practiced by these greasy, dirty men as well[3]. These feminists do not appreciate the lack of masculinity displayed by these men, and therefore, their character is socially unacceptable; they believe what makes these men “despicable” are their lack of self-care and thrifty, money-saving lifestyle[4].

These feminists and those alike think that their poverty or uncertainty-driven behaviours, which are an integral part to their thrifty lifestyle, were valued in socialist China when the lower class were seen as heroes and praised; however, in current-day Chinese society, “Chinese masculinity” and masculinity generally are defined based on one’s showing of their wealth and their drive towards spending and consumerism - ideas voiced by Feng in his article as well[4]. The popularity of this keyword is growing as an increasing number of Chinese people and those with Chinese roots are pointing out the undesirable traits associated with a “greasy, dirty man”.

“How to Avoid Becoming a Greasy, Dirty Middle-Aged Man”

An abridged version of Feng Tang's (冯唐) list of ten (10) pieces of advice is as follows:[5]

- Never become fat; the first impression of greasiness comes from your weight.

- Never stop studying; if you are ugly and reaching middle age, you should study harder.

- Exercise.

- Never talk about sex in the public, unless you are a porn writer.

- Never recall the good old days, even if you are an old military general.

- Do not lecture young people, especially women (i.e. “mansplaining”).

- Do not bother others.

- Never stop shopping; if you lose desire for nice things, life becomes boring.

- Do not be sloppy; when you were young, that’s a wild style; when you are getting old, dirty is dirty.

- Do not be prejudiced against another person’s habits, whatever their age.

Glossary of Explicit Dictionary Meanings

Historical Definitions

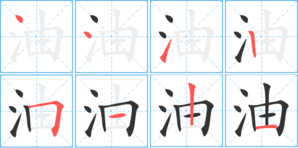

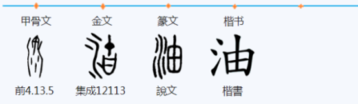

油 (yóu) is a pictophonetic character consisting of a semantic part 氵(water)and a phonetic part 由 (By). 氵(water) represents the form of 油, and "由" represents the meaning and also indicates the pronunciation. In the oracle bone inscriptions, there was only "由" but not "油". 油 (yóu) was appeared in the Bronze inscriptions of the Shang Dynasty, at that time, 油 (yóu) did not mean greasy but used to mean oil. However, It is used very rarely. More importantly, It is not written as "edible oil" because at that time people did not specifically extract oil from animals as a cooking seasoning. But In the Qin Dynasty, 油 (yóu) was widely used as "edible oil". According to the《Zhou Li》, at that time people had invented three ways to use oil for cooking: cooking with food, applying oil to the food, to fried food. In the Han Dynasty, people discovered vegetable oil, so 油 (yóu) also refers to vegetable oil[6]. In the Qing Dynasty, the term "greasy" has been greatly developed. It can refer to the smell of oil, floral fragrance, ointment, lip gloss, and even modify the style of poetry[7].

Contemporary Meanings

油 (yóu) can be used as a noun, adjective, and verb in Chinese, so it has different meanings. Nowadays, 油 (yóu) is often used as a noun and adjective. As a noun, most of the time it refers to animal fat and lipids extracted from plants or minerals. As an adjective, it can express a variety of meanings, and the most extended morphology which is mostly related to oil such as: greasy (油腻). As a verb, it appears in ancient classical Chinese most of the time, for example: "以珍膏(油)其面" - Cai Xiang's《茶录》. It means to apply cream on the tea surface[8].

Examples[8]

- 油 (yóu) - noun

- 鱼油 (Fish oil), 橄榄油 (olive oil): It is a lipid substance extracted from animal fat and plant.

- 煤油 (Kerosene), 汽油 (gasoline):It is a liquid that can be used as fuel extracted from minerals.

- 揩油 (kāi yóu): Used to describe behavior that takes advantage of others. It also refers to sexual harassment of women.

- 油 (yóu) - verb

- 油窗户/yóu chuāng hù/: apply oil on the windows.

- 油 (yóu) - adjective

- 油嘴滑舌/yóu zuǐ huá shé/: Use fancy words to please others. it can refer to a person being dishonest.

- 油光可鉴/yóu guāng kě jiàn/: Describe very bright and moist.

- 油油以退 /yóu yóu yi tui/: Leave in a gentle and respectful manner.

- 云之油油/yún zhī yóu yóu/: Often used to describe how clouds and water flow.

- 油腻 /yóu nì/: greasy. Before the Qing Dynasty, it was usually used as the noun "greasy" to express the oil stains on clothes; it also refers to grease. For example: Poems of Su Shi's <与蔡景繁书>, No. 12: "情爱着人如黐胶油腻" which means that two people in love are sticky like ointment[9].

Greasy in Chinese Popular Culture and Around the World

The single character 油 (yóu) itself is neutral in its original reference to oil or grease in the general terms of cooking oil, oil stains, petroleum, and more. However, when combined with the character 腻 (nì) in modern contexts, this latter character carries the greater implication of the feelings or perceptions of the recipient. Today, the term generally carries the nuance of something being oily to the point of it being too much, which causes one to be fed-up[10].

Academia, Popular Press, and Online Discussions

In their book that studies modern urban Chinese masculinities, The Cosmopolitan Dream: Transnational Chinese Masculinities in a Global Age (2018), Song and Hird listed what they have identified as the "key characteristics of Chinese masculinities in the context of globalization[11]" that reflect changes as a result of cross-cultural interaction:

- Anxiety about the quality of Chinese men vis-à-vis Western men

- The interactions of discourses of masculinity and nationalism

- The role of consumerism in the construction of masculinities

- The increasing association of masculine success with money

- The turn to men’s needs in society spurred by the influence of men’s movements in the West[11]

In a later chapter of the book, Pamela Hunt conducts a case study on Feng Tang and his particular construction of masculinity through his literary career. Hunt relates back to the major principle of the inevitable comparison of Chinese men against Western men that was bound to happen when China's economic reform opened it up to the world in the 1980s. During this time influences from the west, in particular Hollywood, encouraged the prevalence of "masculinist, macho, and sexually aggressive male characters[12]" in books and films as a result of China's own anxiety and uncertainty of its own masculine ideals. This sort of portrayal can be seen to have laid the foundation for the "greasiness" that has become criticized in the discourse that is the focus of our study.

Similarly, Feng Tang has built his literary persona by the particular way of intertextuality - by constantly mentioning his admiration for established foreign and Chinese authors like D.H. Lawrence, Henry Miller, and Sima Qian and in a way associating himself with the literary personas of a group of marginal, subversive writers.[13] It is suggested that Feng, in self-consciously making these allusions to British and American authors, is also identifying with the idealized postsocialist male who is "well read, and, by implication, well traveled and (as it were) well monied.[14]" These ideals and expectations for cultural cosmopolitanism are thus likely to have been part of the inspiration for his essay outlining advice to avoid becoming a greasy man.

The People's Daily as state media, took an innocuous stance when it commented on the popularity of the internet slang in a column published November 2017. The writer avoids specific references made to men and other gender-specific issues as Feng Tang did in his original article, but rather reasons that greasiness is essentially an issue of excess. Types of excessive behavior include: an excess pursuit of personal interests and hobbies, an excess of self-esteem that causes one to forget to be humble, and an excess of desire without sufficient self-control. The column concludes by suggesting that the solution to all this being a continued pursuit of learning, introspection, and self-discipline. [15]

In the mass media, portal side Sohu published a ranking in November 2017 that named the “Top 10 Greasy Middle Aged Male Stars[16]” that was the result of a survey of entertainment journalists. Using a satirical tone, it pokes fun not only at the physical appearance including how they dress, but also points out their behavior including answers they have given in past interviews or social media posts that constitute one as greasy.

In August 2019, an internet user posted a fan edit that named four celebrities: Yang Shuo, Huang Xiaoming, Chen Sicheng, and Zhou Yiwei as the "oilfield four" 油田四子 (Yóutián sì zi). The implication of the phrase was that their greasiness was to the point that it could only be measured in terms of the scale of an oilfield. It is important to note that the 2 minute 20 second long video compiles not only scenes from the actors' theatrical works in which they play overly confident male characters, but includes actual remarks made by them in reality shows or interviews that suggest that these men truly had greasy personalities. To this date, the video has generated over 20 million views on Sina Weibo[17].

Related Expressions and Phrases

Chinese Aunties 中国大妈 (zhōngguó dàmā)

While the term dàmā (aunt/auntie) originally was used as an affectionate term to describe middle-aged women, the connotations of this term changed in 2013 when it was first used by Chinese writer Song Hongbing and later spread to English-language media to refer to female investors who had blindly invested in gold, expecting to earn profits from the low prices they purchased at. Their strategy was unsuccessful, and since then the term evolved and began to be used in mainstream media to ridicule older women who are thought to be uncultured and stubborn, while often gathering in public squares to dance and gossip. It has been described as a ageist and classist slur[18], and can thought of as the female equivalent to the "greasy middle-aged man".

Little Fresh Meat 小鲜肉 (xiǎo xiān ròu)

While also used as a term to identify men, in particular celebrities as well, it is considered the polar opposite of the greasy, middle-aged man, as it describes someone who is young, fit, and generally attractive while exhibiting characteristics of more soft masculinity[19]. This term dates back to at least 2014, when Sina published a list of the top 10 most popular "little fresh meats" in the entertainment industry that year[20]. It has been argued that while some may view this term with negative connotations, being called obscene or objectifying men, it is a reflection of how Chinese women are turning around the traditional male gaze[21] and using their increased buying power in the consumerist market to reflect their ideals of masculinity. Rather than the state-approved version of masculinity that has been promoted in the form of "tough, authoritative, and patriarchal characters" in mass media, there has been an increase in male protagonists in TV and film that are "little fresh meat" who possess qualities of being "beautiful, understanding, and inoffensive[19]" that are widely popular amongst female viewers.

Leftover Women 剩女 (shèngnǚ)

A derogatory term that refers to women, often in their late 20s to 30s or even older who are unmarried, or "left over" from the dating and marriage market[22]. They are often highly educated and seek economic freedom[23] but often still feel pressured by family society to marry and have children because of the social stigma that they face otherwise. The Chinese government has encouraged discourse in mainstream media like producing cartoons and organizing speed-dating events that reinforces the stereotype that unmarried women are unhappy and unfulfilled[22] in order to help with dropping birth rates and implications it has for the next generation's labour supply and economic development[23].

Counterpart Terms of Greasy in Non-Mandarin Languages

English: sleazy

In English, the term sleazy shares a similar meaning to “greasy” in Chinese. The term is defined as “morally bad and low in quality, but trying to attract people by a showy appearance or false manner”[24] which accurately captures the way greasy men are described in Chinese popular press. In Western culture, “sleazy” is often used to discuss political or social leaders who have been caught in sex scandals. Particularly, these sex scandals involve a male leader who has cheated on his wife and draws public attention due to his status as an individual that is influential in society.[25] Furthermore, “sleazy” is used in the context of describing contemporary popular culture in the West and how the heavy use of sexual references in the media has created a pornography culture. For example, in Beyonce’s music videos she grinds on a stripper pole while being pawed by her husband and being caressed by women.[26] The highly sexualized world of pop music and celebrities has raised concerns amongst parents who worry about how it could distort the perspectives of the younger generation.

Japanese: abura gitta

In Japanese, the closest counterpart term for “greasy” is abura gitta (脂ぎった), which refers to someone who is overly persistent, assertive, and crude and is often used to describe middle aged men.[27] The term can also refer to the physical state of a person who is glistening with oily skin.[27] In Japan, abura gitta is used in the context of describing men who are pedophilic and have a sexual desire towards young women. It is used with a negative connotation now as Japanese women have a strong preference towards fresh and cute looking men over men who have very masculine and bold features.[28]

Korean: neukkihada

In the Korean laguage, the term neukkihada (느끼하다) has an almost identical connotation; while it is generally used to refer to foods that are oily to the point of nauseating and overwhelming, it is also used in popular culture to refer to one who “make others feel rather nauseated."[29]

German: schmieriger

In German, the adjective schmieriger while also referring to something greasy as a physical state (an abundance of grease or fat), when used in colloquial means, usually refers to men who similarly “overtly polite, but with an underlying arrogance and possessiveness”[30]

Social, Cultural, and Political Problems of Greasiness

Gender Issues: Employment, Education, and Marriage

Following the publication of Feng Tang’s article, Feng himself started to receive criticism for being a greasy man himself and for being someone with “straight male cancer[31],” an expression used to refer to the regressive, heteronormative behavior of unenlightened men and widely used in the #MeToo movement in China. The article itself stirred many conversations and greasy men have received much criticism from feminists in China as these middle aged men come off as being sexist and patriarchal. For instance, in October 2016 the online commentator Wuyuesanren made a comment that “any woman was attainable for older men such as himself, men with life experience and solid financial footing” and that “spoiled women, or those who rely on their good looks have no value other than as arm candy or in bed.”[3]

While the person who sparked the conversation about greasiness, Feng Tang, is a man, the term is assumed to be mainly used on an everyday basis in popular culture by women of all ages. In parodying and expressing commentary on Chinese men, it can be seen as a way for women to not only start participating, but also taking initiative to direct discourse in mainstream culture about the social and cultural problems of unrealistic beauty standards and gender inequality that women have been subject to.

By pointing out the physical attributes of greasy men with their overweight and unkempt hairstyles, in a way it subverts the traditional gaze of men and their long-established beauty ideals placed upon women to have relatively slim figures and long, silky hair. It places men in a similar position that women are in since a young age, allowing them to experience the same repercussions when one falls out of line with societal expectations.

Beyond its remarks to outer appearances, perhaps the heart of the matter is how the emergence of the term as internet slang became a way for women to discuss gender relations in postsocialist China. Partially an unintentional result of the now-defunct One Child Policy, urban families that gave birth to a female child poured their resources into their only child. These girls grew up with more opportunities to receive higher education, for comparison, before the One Child Policy while females made up only 30% of university students, for those born between 1990 and 1992, that number rose to an even 50%[32]. Thus women are increasingly employed in jobs that provide them with financial independence. It is reported that compared to 1995, when only 10% of executive positions in companies were being held by women, in 2020 that number was up to around 25%, and that women now account for more than half (55%) of new startups in the internet sector[33]. Accordingly, this also means that heterosexual women start having higher standards in regards to romantic relationships and marriage; their primary goal is no longer simply finding someone who can provide for them financially[34], but is also someone who can be a understanding, respectful partner.

In fact, in 2015 even before Feng wrote his article, women were already seen to be starting conversations on the topic of "Why Chinese men give us a greasy feeling" online on Linglong, an e-commerce platform whose userbase is women[35].

Referring back to the video of the Oilfield Four, the male celebrities with their fame and fortune are some of the most privileged figures in popular culture. But by creating these memes and parodies of them on social media, it provides female viewers with a platform to channel their dissatisfaction towards their misogynistic and disrespectful behavior. For example, remarks by Zhou Yiwei included show him referring to his wife as “unprofessional” and suggesting that the level of her work was incomparable to his own in terms of importance[17]. Some of the top-rated comments below the video have users calling Zhou "trash" and "beyond help".

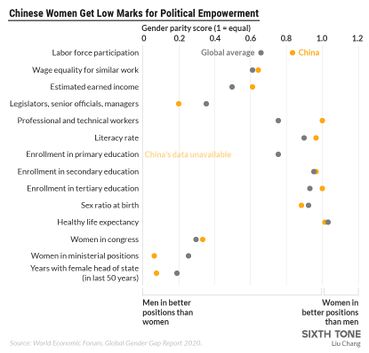

Yet seemingly even with more access to education and employment, there is still the clear awareness that systemic bias towards Chinese women is present. While the Labor Law of China supposedly prohibits gender discrimination, there are still many cases of women bei[36]ng arbitrarily dismissed because of pregnancy and there were 11% of civil service job postings in 2020 that specified that they were only hiring men[37]. Furthermore, since 2008 China's ranking in the World Economic Forum's Global Gender Gap Report has continued to fall. In the most recent edition published in December 2019, China's ranking fell another three places to 106th out of 153 countries listed[38].

The Mid-Life Crisis

Another social problem reflected by the popularity of this term is the overall middle age crisis experienced by Chinese people in general, but perhaps affects men in particular. The term is sometimes even used as a way of self-deprecation, in their attempt of compromising with reality while feeling anxious towards the future. On the one hand, even if this part of the population have managed to attain a certain level of social status and material wealth along with China's rapid urbanization, a looming sense of dread starts appearing as they become aware of the depleting opportunities in the workplace while facing competition from the younger generation that is more educated and qualified than ever before. At the same time, they are increasingly aware of their mortality[3] as the signs of aging start to surface. They are less aware of trends, and because many spend most of their day at work, have little time for exercise and in maintaining their appearances. Over time, it leads to obesity and fashion choices that are ridiculed as being greasy[39].

This phenomena has also spread to the millennial generation of China. An article entitled "90s Kids, Your Midlife Crisis Has Already Begun" became viral in 2017 as well as it highlighted the common premature worry from a generation feeling that they are left unsatisfied and unable to find fulfillment at work[3] due to the long work hours and relatively low pay. As a result of the lack of opportunities for social mobility that is felt by this group, they have been called less ambitious but at the same time more cynical than those before them. They are also seen adopting lifestyles that are more like the generation before them criticized for being greasy: dressing more warmly and practically, drinking less, and sleeping earlier[36]. Memes that reflect this reality, poking fun at the generation born post-1990 have also been created.

Related Studies

The Cosmopolitan Dream:Transnational Chinese Masculinities in a Global Age (2018), a publication edited by Derek Hird and Geng Song provides an in-depth look at the characteristics of modern Chinese urban masculinity, both locally (in China) and internationally.

Ethnographic Studies

In this publication, author Xia Zhang introduced her audience to the term “North American Despicable Men”, or “北美猥琐男”, which directly targets a large population of Chinese male graduate students who are studying abroad[4]. These North American Despicable Men share many traits and qualities to the group of people Feng referred to as the “greasy, dirty men”, with a notable difference being their younger age.

This term emerged from the population of overseas Chinese female students who has drawn comparisons between their male counterparts and local male students who grew up in the West. They explained that their male counterparts are “untidy, skinny, and physically unattractive”, in comparison, but most significant of all, has very few respectable social skills[4]. In Feng’s article titled “How to Avoid Becoming a Greasy, Dirty Middle-Aged Man”, he mentioned the great importance of spending and consumerism, yet, these North American Despicable Men has numerous money-saving habits instead - such as driving a Honda Accord even after achieving relative success, or constantly searching for coupons and featured deals - which has led their female counterparts to shame them with the phrase “not masculine at all” or “完全没有男人味”[4].

From an alternative point of view, author Xia Zhang suggests that deeming a population of Chinese men as “not masculine” or “out-of-touch” is relative, and factors such as race, social class, and recent geopolitical shifts in contesting and negotiating the meaning of Chinese masculinity plays a major role in determining the fit of these students abroad[4].

Film Studies

The third chapter of the The Cosmopolitan Dream (2018), "Transnational Chinese Masculinity in Film Representation" focuses on the depiction of transnational Chinese masculinity in selected films directed by Hong Kong directors from the early 1990s to the present time. The study focuses on three films: Farewell China (愛在別鄉的季節, 1990), Comrades: Almost a Love Story (甜蜜蜜, 1996), and American Dreams in China (中國合夥人, 2013). These three films involve Chinese male characters traveling to America (New York City) in pursuit of the “American dream”, while portraying how Chinese masculinity has evolved from a suffering male figure in the 1980s to an inquisitive male around 1997, and finally an empowered, confident male in the 21st century. In Farewell China (1990), male protagonist Zhou Nansheng illegally enters the United States to find his wife Hong who he lost contact with, but gets nowhere and meets a tragic end.[40] This demonstrates how a traveling Chinese male is not truly transnational and that they cannot protect their wives and families nor can they survive by themselves either. Comrades: Almost a Love Story (1996) was released on the eve of Hong Kong’s return to the mainland, portraying a male protagonist Xiaojun who moves to New York City from China.[40] In filmic representation, mainland women seem to be able to make a transition more easily than mainland men as seen in Comrades: Almost a Love Story, as Li Qiao comfortably adapts to the pace of capitalist lifestyle of Hong Kong while it takes a longer time for Xiaojun to adapt.[40] Hence, this indicates how headstrong socialist masculinity takes more time to change than flexible femininity. American Dreams in China (2013) depicts three male characters: Cheng Dongqing, Meng Xiaojun, and Wang Yang who are best friends and Chinese business partners.[40] The three male characters in the film represent a new generation of Chinese males: white-collar workers, business leaders, well-educated, urban, and cosmopolitan. The resurrection of Chinese masculinity in films of the 21st century corresponds to the the “rise of China” in the age of globalization.[40]

Culinary Studies

In the chapter Tasting Food, Tasting Nostalgia: Cai Lan’s “Culinary Masculinity” [40], author Jin Feng notes that cooking was traditionally thought of as a female-dominated field in China because it was part of domestic responsibilities for women in families. There was even the old saying that only by cooking at home, women can ensure the harmony and prosperity of the whole family. For a long time in history, men who cooked or demonstrated a passion for doing so were sometimes regarded as greasy or lacking in masculinity. As history progressed, many men from the elite classes, particularly in popular culture have continued to participate and produce much of the literature about food in Chinese culture. One of these leading figures is Chua Lam (also known as Cai Lan), famous food critic, television host, and restaurateur. He considers himself a mature and knowledgeable person. Chua has remarked on how a pre-modern Chinese gentleman was defined by "his knowledge and skills in diet," and therefore, has advocated for a revival in the learning of culinary knowledge in his literary and television work. In his shows he informs the audience about the traditional history and culture behind the dishes and ingredients, so the audience is able to learn and have a newfound appreciation about traditional Chinese culture while also appreciating the visual presentation of the food. As a result, Chua has been lauded for his knowledge and skills in successfully integrating various cultural influences like Confucianism and modern individualist values in his way of constructing his masculine identity. In other words, Chua constructed his masculinity by participating in the same social network of male-dominated Chinese cultural traditions. Through this case study, Jin demonstrates that cooking, something that has been thought of as domestic, feminine field, can also be used to promote the formation of masculinity, in Chua's case, even more so than established art forms such as literature, music or art[40].

Conclusion

Ultimately, like many subcultures and mainstream trends in Chinese contemporary culture, the emergence of the neologism of greasy and greasiness does not seek to actually challenge the status quo or direct dissent towards official institutions that are perhaps the ultimate deeper root cause for social and political problems mentioned above. The awareness of censorship and persecution is constantly present on the minds of everyone that operates in the sphere of mass media, whether as a user or content creator. Rather, as mentioned, it provides a way for internet users, specifically women to navigate and find ways to empower their voices in what still remains a mainly patriarchal society in contemporary China. They are no longer passive, silenced audiences, but rather able to use new technologies and platforms to engage in textual poaching[41], (re)making and circulating meaning through their own cultural products.

Through examining the counterpart terms of the term “greasy”, it can be deduced that the meaning of the keyword has both similarities and differences across different cultures and countries. In China, greasy is used primarily to describe the way middle aged men present themselves physically and verbally. Similar to Japanese and English, greasy men in Chinese points to middle-aged men in their 40s or 50s as having a grubby appearance and reports of marital infidelity and sexual harassment involving younger women. Another universal meaning extracted from the discussion of greasy men in China is how middle aged men as an age group in both Asian and Western cultures commonly experience a midlife crisis so they feel emotionally unfulfilled, nostalgic for their fading youth, as well as lusting after money, comfort, and power.

As seen from the related keywords and further analysis, it seems as though one is unable to escape labels and stereotypes no matter what age, marital status, or gender group they are a part of. On a deeper level, they are a reflection of our insecurities, ignorances, and biases, whether it is towards oneself or reflected in our grouping of others.

In the future, it would be intriguing to see ethnographic research conducted to find out how being called a "greasy" man or any other of the aforementioned terms might influence one's self-perception and consequently, their actions and choices in their everyday lives. Labels and stereotypes are known to have implications on one's psychology and social relations, and so it would be of great interest to see the reverberations of what started out as internet slang have on the actual lives of people. As the presumed critics of greasy men, like heteronormative women and even LGBTQ in China, it would also be interesting to hear their feedback and opinions on the term and if they feel that using the term and participating in relevant discourse whether online or in real life reflects changes in gender relations and power dynamics.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Kou, Jie (December 21, 2017). "China reveals hottest internet slangs of 2017". 人民网. Retrieved November 6, 2020.

- ↑ Feng, Tang (2017-10-27). "如何避免成为一个油腻的中年猥琐男". Sina Weibo. Retrieved 2020-11-15.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Zeng, Yuli (2017-11-08). "Meet China's New Fall Guys: 'Greasy' Middle-Aged Men". Sixth Tone. Retrieved 2020-11-06.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Derek Hird and Geng Song (2018). The Cosmopolitan Dream: Transnational Chinese Masculinities in a Global Age. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. pp. 218–236. ISBN 978-988-8455-85-0.

- ↑ Sun, Jiahui (2017-11-09). "Grease is the word". The World of Chinese. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- ↑ QINGNIANSHU YU (2018). "《二》油——人的第六种味觉". Fangweb.

- ↑ SUN, BAOXIN (2018). "常用词"油腻"的来源、演变与发展". CNKI. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 HAN Dictionary (2020). "油 基本解释". Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- ↑ ZONG, SHIYONG (2018). ""油腻"的流行及其他". CNKI. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- ↑ "腻 (膩)". Collins Dictionary. Retrieved 2020-11-06.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Derek Hird & Geng Song (2018). The Cosmopolitan Dream: Transnational Chinese Masculinities in a Global Age. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. p. 7. ISBN 9789888455850.

- ↑ Derek Hird & Geng Song (2018). The Cosmopolitan Dream: Transnational Chinese Masculinities in a Global Age. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. p. 107. ISBN 9789888455850.

- ↑ Derek Hird & Geng Song (2018). The Cosmopolitan Dream: Transnational Chinese Masculinities in a Global Age. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. p. 103. ISBN 9789888455850.

- ↑ Derek Hird & Geng Song (2018). The Cosmopolitan Dream: Transnational Chinese Masculinities in a Global Age. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. p. 110. ISBN 9789888455850.

- ↑ "透过皮相看油腻". People's Daily. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- ↑ "十大中年油腻男星排行榜:杨烁占榜首,黄晓明出局". Sohu. 2017-11-09. Retrieved 2020-11-07.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 根正苗红好颜狗. "油田四子 之 霸道总裁爱上我". Sina Weibo. Retrieved 2020-11-06.

- ↑ Teng, Wei (2018-10-25). "'Dama': A History of China's Ageist, Sexist Slur". Sixth Tone. Retrieved 2020-11-15.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Wu, Haiyun (2016-08-16). "How 'Little Fresh Meats' Are Winning China Over". Sixth Tone. Retrieved 2020-11-15.

- ↑ "鹿晗领衔2014娱乐圈最受欢迎的十大人气小鲜肉". Sina. 2014-06-05. Retrieved 2020-11-15.

- ↑ Gao, Helen (2019-06-12). "'Little Fresh Meat' and the Changing Face of Masculinity in China". The New York Times. Retrieved 2020-11-15.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Lewis, Helen (2020-03-12). "What It's Like to Be a Leftover Woman". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2020-11-15.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Usher, Pip (2016-10-04). "Unmarried and Over 27? In China, That Makes You a "Leftover Woman"". Vogue. Retrieved 2020-11-15.

- ↑ "Meaning of sleazy in English". Cambridge Dictionary. Retrieved 2020-11-06.

- ↑ Seattle Times staff (2011-06-11). "What is it with these sleazy men?". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 2020-11-07.

- ↑ Moir, Jan (2015-09-11). "JAN MOIR: How today's sleazy pop culture makes young girls dress like Vegas croupiers". The Daily Mail. Retrieved 2020-11-07.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 "脂ぎった". Weblio. Retrieved 2020-11-06.

- ↑ Mynavi Corporation (2018-05-09). "女性にモテる男性の特徴・共通点ランキングTOP15". Mynavi News. Retrieved 2020-11-08.

- ↑ "느끼하다". Naver. Retrieved 2020-11-07.

- ↑ "schmierig". Wiktionary. Retrieved 2020-11-07.

- ↑ Hunt, Pamela (2019-02-01). "Literary Heartthrobs". China Channel. Retrieved 2020-11-07.

- ↑ Dawson, Kelly (2019-09-29). "China women still battling tradition, 70 years after revolution". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 2020-11-15.

- ↑ Li, Wen (2020-10-02). "25 years of gender equality in China". CGTN. Retrieved 2020-11-15.

- ↑ Schmitz, Rob (2018-07-31). "China's Marriage Rate Plummets As Women Choose To Stay Single Longer". National Public Radio. Retrieved 2020-11-15.

- ↑ Fan, Liya (2017-11-01). "Advice on How Not to Be a Sleazy Man Kicks Up Weibo Storm". Sixth Tone. Retrieved 2020-11-15.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Liang, Chenyu (2017-12-18). "Are China's Millennials Already Over the Hill?". Sixth Tone. Retrieved 2020-11-15.

- ↑ "China: Gender Discrimination in Hiring Persists". Human Rights Watch. 2020-04-29. Retrieved 2020-11-15.

- ↑ Xue, Yijie (2019-12-19). "China Falls in Global Gender Equality Rankings, Again". Sixth Tone. Retrieved 2020-11-15.

- ↑ 王卫池; 李琛 (2019). ""中年油腻"的社会戏谑与现实再反思". 南京林业大学人文社会科学学院: 237–239.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 40.4 40.5 40.6 Derek Hird and Geng Song (2018). The Cosmopolitan Dream: Transnational Chinese Masculinities in a Global Age. HK: Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. pp. 150–158. ISBN 978-988-8455-85-0.

- ↑ "Textual poachers". SAGE Reference. Retrieved 2020-11-15.

| This resource was created by the UBC Wiki Community. |