Course:ARST573/Performing Arts Archives

The mission of performing arts archives is to preserve documentation of the historical and organizational aspects of the performing arts, as well as the people or organizations that create them, for scholars and the general public.[1] This documentation can be generated at any point in the progression from creative inspiration to ultimate performance.[2] In addition, performing arts archives attempt “to capture the art form’s essence and spirit."[3]

Performing arts archives can be housed within particular dance, theatre, or other performing arts companies, with a commitment to document just those companies, or can be housed within a special collections archives or library, with the mission to document all performing arts communities within a particularly area, region, or country. Other performing arts archives can focus on a specific individual, art form, topic, or target audience.[4]

The nature of performing arts

The performing arts are ephemeral—they are experienced by an audience visually and aurally in real-time and are not fixed or lasting.[5] The challenging and paradoxical role of performing arts archives is to preserve print and non-print materials that give some measure of stability and permanence to these ephemeral performances.[6] Performing arts can include all types of theatre, live music, dance, opera, cabaret, mime, street performance, puppetry, circus, vaudeville, and more. They can take place most anywhere and can consist of single performances or be part of larger festivals, tours, or seasons.[7] Despite the diverse and wide-ranging nature of the performing arts, much of the current literature within the archival field and the performing arts community focuses on dance and theatre archives.

Unique materials

The materials in a performing arts archives should ideally reflect all aspects of the art, from the initial creative process, to the management and funding of the organization, to the performance and reviews.[8] The preservation of this evidence is extremely important as, without archival materials performing arts artists and companies "would be unable to learn from past successes or mistakes or plan for their growth and development."[9]

Textual material and ephemera

In addition to those materials commonly found across all archival repositories, the types of records unique to performing archives include choreographers’ notation records, performance logs, production notes, stage managers’ reports,[10] designs, drawings, scripts, music scores and orchestrations,[11] among others. There is also a good deal of ephemera in performing arts archives, perhaps more than in other types of archives. Important performing arts ephemera includes programs, show reports,[12] press releases, press coverage, reviews, flyers, posters, postcards, invitations, and tickets.[13] Ephemera may also include non-print promotional materials, such as clothing, jewellery, badges, and other souvenirs.[14]

Audio-visual material

Audio-visual material, including analog and digital photographs and analog and digital video, may represent the most important and also most vulnerable of the material performing arts archives acquire.[15] Unlike the documentation of the supporting activities, audio-visual material comes closest to actually documenting performances themselves—capturing movement and sound in a way that other static forms of documentation simply cannot. Video or audio oral history is also important in documenting the lives of important figures in the performing arts community.[16]

Costumes, props, and other objects

Other materials unique to performing arts archives include costumes and props, both of which present special preservation concerns and housing requirements.[17] An alternative to storing costumes themselves is the “costume bible,” which might include sketches, technical drawings, photographs and descriptive inventory, and which may be useful for documenting costumes, as well as recreating costumes for revivals of performances.[18] In addition, performing arts archives can include other three-dimensional objects such as set models, scenery, painted backcloths, and furniture.[19]

Value to researchers

Performing arts archives may be used in a number of ways, including for scholarly research, live performance development, media, celebrations and exhibitions, publications, and internal use.[20]

Scholarly research

Typical scholarly researchers may include "graduate students writing theses, doctoral students researching dissertations, post-doctoral researchers writing articles, teaching faculty preparing graduate seminars, and authors writing biographies, cultural studies, reference works, and trade books."[21] In addition to their value to performing arts scholars, performing arts archives can be vital to research in other disciplines, including exile and emigre studies, women's studies, interdisciplinary studies, legal analysis, genealogy, literary history, and other cultural studies.[22] Although scholarly research tends to add legitimacy to the value of performing arts archives, materials are more often used "to enrich more immediate cultural offerings."[23]

Live performance

Members of the performing arts community, including performers, directors, designers, choreographers, and others use performing arts archives to "identify new repertory, plan programs, research past performances and productions, reconstruct original performances, and generate ideas for new productions."[24] Assisting the members of the performing arts community in developing new ideas through the use of archival materials is one of the most creative aspects of administering a performing arts archives.[25] Archival materials can be used to stage newly discovered scenes of plays, perform early and unknown compositions by well-known composers, reconstruct choreography through letters and printed music, and reconstruct staging from images of stage projections.[26] Performing arts archives and archivists can also assist performances "by making hard-to-find editions and/or recordings available for study, providing translations of texts or transpositions of songs, answering questions about printing errors, providing information and historical documents for program notes, and answering questions about publishing and performance rights."[27]

Media

Managing the use of performing arts archival materials for electronic media, including use in television, film, or commercial recordings, creates challenges for performing arts archivists regarding copyright.[28] Reference inquiries related to commercial recordings may include requests for unpublished music, historical information or photographs for liner notes, verification of titles, and more.[29] Documentary filmmakers often wish to use performing arts archives because of easy access to unique materials, however, these are labor-intensive projects requiring "complex licensing arrangements, making special arrangements for the camera crew to film 'on location' in the repository, and working with researchers who have scant knowledge of their subjects."[30]

Celebrations and exhibitions

The historic materials in performing arts archives become especially valuable to people and organizations marking notable milestones, celebrating anniversaries, or otherwise planning events.[31] Archives can facilitate the planning of international festivals, film series, symposia, conferences,[32] exhibitions, and the publication of books marking important occasions or accomplishments.[33] In addition to mounting their own exhibitions, performing arts archives may loan materials to established venues for display.[34]

Publications

The inclusion of performing arts materials in print publications is a popular way of increasing access while preserving the original, vulnerable documents and objects.[35] In particular, the publication of correspondence by well-known members of the performing arts community is a common use of archival materials that also increases awareness of the correspondents and the archives.[36] Publication of sheet music, collected writings, and interviews are also common.[37]

Internal use

Staff of a particular performing arts company may use its own archival repository frequently in order to answer questions pertaining to licensing and copyright administration, as well as for promotional activities.[38] Archival materials may be used to prepare brochures, newsletters, and to create website content.[39] Materials can also be used to learn from past administrative successes and mistakes.[40] Operational and administrative materials that may be frequently consulted include those related to ticket sales, publicity and marketing strategies, legal contracts, grant-writing, administrative correspondence, production and company financials, fundraising campaigns, and board of directors’ meetings.[41]

Challenges

While performing arts archives encounter many of the same issues as other repositories, they also face unique challenges. These include restricted hours of operation due to a lack of staffing, a more limited patron base, a reliance on donated materials in the absence of acquisition budgets, access restrictions, and special preservation concerns due to the predominance of ephemera and audio-visual materials.[42]

Lack of funding

Many performing arts archives rely exclusively on donations to build their collections due to a lack of funds for acquisitions.[43] Performing arts archives that are part of a larger institution may have a modest budget for acquisitions, but stand-alone performing arts archives or archives that are maintained by a particular performing arts company are rarely in the position to purchase materials. While performing arts archives overwhelmingly share the mission of providing access to materials, lack of funding and the accompanying lack of staff results in many performing arts archives having only limited hours of operation. Because of this, many performing arts archives require advance notice and an appointment in order to access materials.[44] Unfortunately, these restrictions to access likely hurt performing arts archives in further limiting an already narrow user group.[45]

Lack of professional staff

Many of the more renowned performing arts archives were established thanks to the efforts a small number of people who were interested in preserving records of particular company.[46] The founding individuals of these archives were seldom professional archivists, but were more likely former performers or administrators with a passion for the art form, but no archival training.[47] Perhaps more than with other types of archival materials, the care and preservation of performing arts documentation can, by design or accident, fall to non-professionals, including performers, choreographers, directors, designers, administrators, or collectors.[48] Sometimes these individuals act only as interim caretakers before materials are transferred to a trusted archival repository. However, for archives housed within performing arts organizations, non-professionals are often the only ones organizing and caring for archival materials. This has resulted in the creation of manuals for non-professionals, such as Dance Archives: A Practical Manual for Documenting and Preserving the Ephemeral Art and Caring for your Theatre Archives.[49] A valuable resource for those without prior archival training, the Dance Archives manual features sections on each of the common formats of dance documentation and the specific appraisal, arrangement and description, and preservation techniques for those formats. In addition to basic archival information, the manual also provides practical examples that non-professional dance archivists can follow, including a sample records retention schedule, a model deed-of-gift agreement, a sample videotape data log, sample series descriptions, box and folder lists, and a sample oral history transcript.

Preservation concerns

Unfortunately, many performing artists and performing arts companies are unaware that their irreplaceable archival materials will not last indefinitely and require particular care and handling.[50] The abundance of ephemera and audio-visual materials creates a number of preservation concerns for performing arts archives, particularly as a lack of financial resources often puts conservation treatments out of reach. Newspaper clippings and other ephemeral textual records printed on highly acidic paper are apt to crumble apart after only a short period of time.[51] Cellulose acetate photographic film is subject to vinegar syndrome as it ages, causing the film to separate and contract, resulting in wrinkling and rendering the image undecipherable.[52] Film and videotape are particularly vulnerable.[53] Older nitrate film can be highly flammable, while newer acetate film is subject to a form of deterioration that shrinks the film, making it unviewable. Each time videotape is played, the tape is exposed to heat, tension, and friction, which wears down the magnetic materials holding the image to the tape,[54] and eventually causing flaking.[55] Sadly, "there are thousands of horror stories of performances and works 'lost' because they were 'preserved' only on videotape.[56] In addition, because of rapid changes in technology, formats may become quickly obsolete, forcing performing arts repositories to collect and maintain out of date playback machines in order to provide access to audio-visual materials.[57]

Many archives are looking to digitization to make audio-visual resources safely available to the public, while freeing up physical space in the archives.[58] However, such digitization projects require funding, time, and a plan for the preservation of digital resources going forward.[59] In addition, digitizing audio-visual materials results in large files requiring a great deal of data storage space, and the digitization process can result in some loss of some visual information.[60] Further, "digital preservation and access is fraught with its own longevity concerns."[61] Benign neglect of digital records often results in their loss,[62] such that the preservation of digital files requires human intervention just as much as analog objects. Digital archives must be regular migrated to new formats in order to avoid obsolesce and file corruption.[63] Digital preservation is becoming more of a concern as digital audio-video is increasingly being used not only to capture and preserve the performing arts but is also being used in the creation and staging of performing arts works.

Balancing access and privacy

While all archivists face the challenge of balancing access to researchers with protecting the privacy of the people whose lives are documented in archival materials, this can be particularly problematic with performing arts materials.[64] The performing arts field is made up of networks of famous or otherwise high-profile individuals, and "the personal papers of an individual entertainer are likely to contain information from and about other celebrities, frequently without their knowledge."[65] Many performing artists "jealously guard their private lives."[66] In addition, the papers of performing artists may contain the personal data of third-party individuals who may have worked for or otherwise interacted with the artists.[67] Issues around privacy and access may become particularly difficult when the donor of the papers is still living. As noted above, many performing arts archives rely heavily on donations to grow their collections. Therefore, maintaining positive relations with donors is crucial for performing arts archives in order to keep open the possibility of additional donations from past donors and to cultivate new donors.[68] It is important that performing arts archivist be aware of the relevant legislation related to information privacy, as well as to engage living donors in conversations regarding access restrictions on materials containing sensitive information.

Documenting the performing arts

Representing impermanence in static forms

Some literature on the topic of performing arts documentation questions whether it is futile to try to capture performing arts through fixed and static representations, since they are by their very nature transitory, fluid, and dynamic.[69] Records that document performance may provide an “access point,” but each record only offers one perspective on the performance, and even multiple accumulated records still may provide only specifics on a certain aspect of the performance, without accurately reflecting the performance as a whole.[70] In order to create more accurate representations of the performing arts within archives, some scholars propose “an open model of archives, encouraging multiple representations and allowing for creative reuse and reinterpretation to keep the spirit of the performance alive.”[71] This may be accomplished by considering as records not only the material representations of performing arts—the physical documentation—but also the immaterial elements—memory and embodied knowledge.[72] By bringing together both material and immaterial “records” within performing arts archives, and representing the process and not just the final product, archives can provide more accurate evidence of these experiences.[73] Further, because a significant property of the performing arts is impermanence, performing arts archives “must be open to change and remain in active use,” moving away from fixity and stability and embracing variability through use.[74] Such use could include archives workshops in which artists explore performing arts documentation as inspiration for new pieces.[75] Performing arts archives may also embrace more “nebulous and contradictory” sources of documentation, such as the preservation of the audience’s collective memory of the performance through oral history, audience research exercises, letters, diaries, etc.[76]

(In)Compatibility with archival science

While the points raised about the limitations of archives in representing and documenting the performing arts are intriguing, they also go against many of the foundational principles of archival science. The concern expressed by performing arts scholars raises questions about how far archivists can and should adapt their theories or practices to better document this aspect of cultural heritage. If nothing else, the issues raised by these scholars provide an excellent jumping off point for discussion around unresolved questions within the archival and performing arts communities. These dialogues may also allow archives to better represent the performing arts and meet the needs of artists and researchers.

Performing arts archivists

Overview of the profession

Until recently, performing arts archives and archivists have been on the outskirts of the field. However, starting in the early 2000s, the effort of performing arts archivists and professional groups and associations such as International Association of Libraries and Museums of the Performing Arts (SIBMAS), the Theatre Library Association (TLA), the Society of American Archivists’ Performing Arts Roundtable (PAR), and the Performing Arts Special Interest Group of Museums Australia (PASIG) have begun to generate more interest in this area.[77] Still, archival scholar Francesca Marini argues that the specialized knowledge of performing arts archivists has not been completely integrated into the larger professional community.[78] Issues relevant to performing arts archivists that should become part of the larger conversation within the field include “issues of arrangement and description of performing arts materials, ethical and artistic considerations in documenting and preserving performances, and knowledge requirements for archivists preserving live theatre.”[79]

Professional characteristics

Following a three-year study on theatre and performance studies researchers, librarians, and archivists, Marini was able to make some observations about the general characteristics shared by many professional performing arts archivists.[80] These characteristics include a thorough knowledge of the context of the materials and at least a partial understanding of the disciplines and fields relevant to the creators and to the users, which may include theatre history, theory, and practice.[81] Their subject expertise, achieved through the acquisition of advanced degrees or as a result of experience working in the performing arts community, helps performing arts archivists become researchers in their own right, allowing them to assist scholars in the interpretation of materials.[82] Performing arts archivists are also particularly engaged, possessing a deep understanding of and participating actively in theatre practice, allowing these archivists to better address the needs of their communities. Engagement also manifests in active promotion of performing arts resources and creative uses of those resources.[83] These outreach and promotion efforts may include publications, seminars and conferences, and other types of community engagement.[84]

Case studies (Canada)

Dalhousie University Archives and Special Collections’ (DUASC) theatre archives

History and development of the theatre archives

The University Archives within the Special Collections Department at Dalhousie University Library in Halifax, Nova Scotia was formally established in 1970, prompting an initial call for donations, including the donation of theatre materials. [85] This call lead to the donation of collections of programs from community, amateur, and professional theatre companies based in the Nova Scotia and from traveling companies performing in the province.[86] Although these were not true archival materials in that they were collections rather than naturally aggregated materials, in the early days of the archives, they were considered important building blocks of the collection. Also among the early acquisitions of the theatre archives were the records of the Neptune Theatre (acquired in 1971), the Theatre Arts Guild, Canada’s oldest continuously running amateur theatre group (acquired in 1973), the Nova Scotia Drama League (acquired in 1974), and the alternative theatre company Pier One (acquired in 1975).[87] The 1980s saw the acquisition of two more major collections. A donation from the University Women’s Club included twenty-five puppets from performances in the 1940s and 1950s, as well as partial scripts, programs, and other related materials.[88] In addition, Robert Doyle, a member of the local theatre community donated costume and set design sketches done for the Neptune Theatre and the Dalhousie University Theatre Program.[89] The 1990s included donations from local actors, directors, and scholars.[90]

Digital and local outreach

The richness of their holdings by the late 1990s, and the desire to promote them, prompted the theatre archives to begin planning a digital collection on the history of theatre in Nova Scotia.[91] The resulting digital resource, From Artillery to Zuppa Circus: Recorded Memory of Theatre Life in Nova Scotia, was created thanks to a grant obtained in 2003–2004 from the Canadian Culture Online Program.[92] The goal of the resource was to document, interpret, and provide access to information and archival resources on the history of theatre in Nova Scotia,[93] and feature profiles of prominent members of the theatre community, photographs, audio clips, and promotional materials.[94] In addition to providing a resource to their researchers, the theatre archives was able to leverage the digital resource as an outreach tool to foster connections with the theatre community and raise the profile of the archives.[95] The archives was able to make the theatre community more aware of their activities during the recruitment of interview participants. As a result, they subsequently acquired records from companies such as Jest in Time, Two Planks and a Passion Theatre Company, Mulgrave Road Theatre, Chester Playhouse, Playwrights Atlantic Resource Centre, and the Ross Creek Centre for the Arts.[96] In addition, From Artillery to Zuppa Circus provided the theatre archives with a resource to educate the public about the nature of archival holdings generally and the resources available in their repository specifically.[97]

The theatre archives at DUASC also works with the local theatre community to educate them on how to prepare their records for eventual transfer to the archives and which records should come to the archives due to their evidential, legal, informational, or historical value.[98] This free records management advice is highly valued by the theatre companies and allows the archives to secure valuable records more quickly and efficiently.[99] The archives also provides support to the theatre community in the form of graduate student interns in records management.[100]

Rights and access

The archives faces challenges related to the resolution of ownership issues with theatre companies who early in the life of the archives had established deposit agreements, but did not transfer ownership to the archives outright.[101] In addition the archives faces other rights management issues particular to theatre holdings, such as performance rights which may restrict the use of photographic and audio-visual materials.[102] The records of some companies may fall under the Canadian Theatre Agreement negotiated between Actors’ Equity and the Professional Association of Canadian Theatres, which limits how the images of Equity members can be used without paying a royalty to the actors.[103] This results in some materials being largely inaccessible for research and reproduction.[104]

Stratford Festival Archives

Overview of the Stratford Festival Archives

Founded in 1967, the Stratford Festival Archives in Stratford, Ontario is “is one of the world’s largest and most complete institutional performing arts archives.”[105] As a store house for the records of “the largest repertory theatre in North America” since its opening in 1953, the Archives represents all aspects of production and administration at the Festival.[106] The Archives is integrated into the daily operations of the Stratford Festival and combines records management, long-term archiving, and exhibition functions. Records and materials are delivered to the Archives by Festival departments throughout the year. Materials are stored in about 10,000-square-feet of space, and are arranged by department and then by year and production.[107]

Materials

The diverse range of materials housed at the archives includes departmental records, sketches, props, costumes, set pieces, photos, video recordings of productions dating back to 1968, as well as sound and audiovisual material dating back to 1953.[108] The Festival enjoys a celebrated reputation for the quality of its design, as well as the excellence of its designers and artisans. As such, the Archives houses records relating to the work of a number of renowned set, lighting, and costume designers who have been a part of the Festival over the years. These include artists such as Desmond Heeley, Tanya Moiseiwitsch, Ann Curtis, Leslie Hurry, Brian Jackson, Patrick Clark, Santo Loquasto, Carolyn M. Smith, Robert Brill, and Robert Perdziola, among many others.[109] Materials related to production design may include set and prop bibles, technical drawings and plans, sketches, inspirational images and materials, photos, video recordings, reviews, as well as the actual props and set pieces.[110] In addition to organizing and preserving materials, the Archives arranges the loan of “some sturdy objects” to Festival productions, provided that they are returned in good condition and are not altered in any way.[111] Objects are also loaned out occasionally for promotional photo shoots at the Festival.[112]

Use of the Stratford Festival Archives

The Archives, which is open five days a week, eight hours a day, serves the needs of the Stratford Festival, researchers, and the general public, welcoming about 1,800 users and visitors each year.[113] Archives staff receive dozens of reference and access requests each day from Festival staff and the public. Common requests include the use of photos for a wide range of purposes including documentaries and publications, requests to view costumes, textual records requests, and more.[114] Similar to photo resources at Dalhousie University theatre archives, the use of production photos and archival videos of productions is regulated by the Canadian Actors' Equity Association.[115] In addition to providing research assistance to visitors, the Archives has a strong commitment to outreach and education, which inspires close collaboration with the surrounding Stratford community, educators, and members of the public.[116] Programs sponsored by the Archives include public screenings, exhibitions, tours, and the creation of a DVD of archival materials.[117] In addition to introducing new users to the Archives, some of these programs generate revenue that can be re-invested in preservation and other projects.[118]

Dance Collection Danse

History and development of Dance Collection Danse

Founded in 1986 by former ballet dancers and husband-and-wife team, Lawrence and Miriam Adams, Dance Collection Danse (DCD) in Toronto, Ontario houses the largest collection of dance material in Canada.[119] The Adamses had both been dancers with the National Ballet of Canada in the 1960s before becoming dissatisfied with the lack of creative autonomy.[120] In 1983, they initiated ENCORE! ENCORE!, a dance reconstruction project dedicated to researching Canada’s dance history.[121] To launch the project, dance instructor Sonja Barton was hired to travel across the country interviewing dancers, teachers, and choreographers.[122] In addition to oral histories, Barton collected “programs, photographs, newspaper clippings, teaching and choreographic notes, reels of film, and other artifacts that people simply handed over to her, all related to the country’s dance history.”[123] As a result of the ENCORE! ENCORE! project, the Adamses “found themselves with a house full of archival material and artifacts,” leading to the birth of Dance Collection Danse.[124]

Materials

DCD focuses particularly on artifacts and records pertaining to theatrical or concert dance in Canada, rather than social or vernacular dance.[125] The organization acquires both archival records and three-dimensional objects. The majority of the collection comes from the twentieth century, though a few artifacts date back to the mid-nineteenth century.[126] Materials are received “from artists, companies, schools, photographers, and administrators as well as from the descendants of dance professionals."[127] Holdings include “approximately 385,000 documents, including business records, souvenir and house programs, photographs, posters, correspondence, postcards, and other items from some 550 individual artists, teachers, and companies; 1,100 hours of oral history interviews; 1,000 moving-image recordings in various media; 250 costumes, props, and set pieces; and 200 art works."[128] DCD maintains an active digitization program for still and moving images, as well as their oral history collection.[129] Material at the DCD is catalogued using the Canadian Integrated Dance Database (CIDD), which was developed by Lawrence Adams and colleague Clifford Collier in the 1990s.[130]

Use of the DCD Archives

Although DCD receives most of its research inquiries from Canada, the United States, and England, requests come in from all over the world.[131] While initially DCD was able to afford only one full-time paid staff person—co-founder Miriam Adams[132]—today the organization has six staff, including a director of collections and research and an archives assistant.[133] DCD is open to researchers weekdays from 9 a.m.-5 p.m., however, research visits to the archives are scheduled by appointment only due to limited space and the fact that materials often need to be retrieved from off-site storage.[134] While access to archival material is free, DCD provides reproductions and tours as fee-based services.[135] In addition to maintaining the archives, as of 2011 DCD had produced thirty-eight books, including biographies, memoirs, cultural studies, manuals, and educational resources, and published seventy editions of its newsletter/magazine.[136]

Institutions and repositories with performing arts collections (Canada)

This partial list was compiled from the SIBMAS International Directory of Performing Arts Collections and Institutions.

Alberta

Provincial Archives of Alberta

University of Alberta Archives

University of Calgary MacKimmie Library Archives and Special Collections

British Columbia

Simon Fraser University W.A.C. Bennett Library Special Collections

University of British Columbia Library Rare Books and Special Collections

University of Victoria McPherson Library Special Collections

Vancouver Public Library Special Collections

Manitoba

Provincial Archives of Manitoba

La Société historique de Saint-Boniface

University of Manitoba Archives and Special Collections

New Brunswick

Provincial Archives of New Brunswick

Université de Moncton Centre d'Etudes Acadiennes

University of New Brunswick Harriet Irving Library Archives and Special Collections

Newfoundland

Memorial University of Newfoundland Centre for Newfoundland Studies

Nova Scotia

Acadia University Esther Clark Wright Archives

Dalhousie University Killam Memorial Library University Archives and Special Collections

Nova Scotia Archives and Records Management

Ontario

Hamilton Public Library Local History and Archives

McMaster University Library William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections

Stratford Shakespeare Festival Archives

Toronto Public Library Performing Arts Centre

Université d'Ottawa, Centre de recherche en civilisation canadienne-française

University of Guelph Archival and Special Collections

University of Toronto Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library

University of Waterloo Library Special Collections

University of Western Ontario Library J. J. Talman Regional Collection

University of Western Ontario Music Library

York University Library Clara Thomas Archives and Special Collections

Prince Edward Island

Prince Edward Island Public Archives and Records Office

University of Prince Edward Island Robertson Library

Quebec

Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec

La Bibliothèque de la danse Vincent-Warren

Bishop's University Archives and Special Collections

McGill University Rare Books and Special Collections

Université de Montréal Division de la gestion de documents et des archives

Université du Québec à Montréal Service des archives et de gestion des documents

Saskatchewan

University of Regina Archives and Special Collections

University of Saskatchewan Special Collections

Yukon

Professional associations and groups (International)

Canadian Association of Music Libraries, Archives, and Documentation Centres (CAML), established in 1971.

Canadian Association for Theatre Research, established in 1976.

Dance Heritage Coalition (DHC), established in 1992.

Global Performing Arts Consortium (GloPAC), established in 1997.

International Association of Music Libraries Archives and Documentation Centres (IAML), established in 1951.

International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives (IASA), established in 1969.

Performing Arts Heritage Special Interest Group of Museums Australia (PASIG), established in the early 1990s.

Société Internationale des Bibliothèques et des Musées des Arts du Spectacle / International Association of Libraries and Museums of the Performing Arts (SIBMAS), established in 1954.

Society of American Archivists’ Performing Arts Roundtable (PAR), established in 1986.

Theatre Library Association (TLA), established in 1937.

Recommended readings

Performing Arts Resources is a monograph series produced by the Theatre Library Association, featuring articles on resource materials in the fields of theatre, popular entertainment, film, television and radio, information on public and private collections, and essays on conservation and collection management of theatre arts materials.[137]

Notable titles in the series include:

- Brady, Susan, and Nena Couch. 2007. Documenting: Lighting Design. New York, N.Y.: Theatre Library Association.

- Calhoun, John. 2012. Documenting: Scenic Design. New York, N.Y.: Theatre Library Association.

- Cocuzza, Ginnine, and Barbara Naomi Cohen-Stratyner. 1985. Performing Arts Corporate Archives. New York: Theatre Library Association.

- Cohen-Stratyner, Barbara Naomi. 1990. Arts and Access: Management Issues for Performing Arts Collections. New York: Theater Library Association.

- Friedland, Nancy E. 2010. Documenting: Costume Design. New York, N.Y.: Theatre Library Association.

- Johnson, Stephen Burge, and Brooks McNamara. 2011. A Tyranny of Documents: The Performing Arts Historian as Film Noir Detective ; Essays Dedicated to Brooks McNamara. New York: published by the Theatre Library Association.

In addition Dance Research, the longest running, peer-reviewed journal in its field, publishes a somewhat regular "Archives of the Dance" article, which provides case studies on particular repositories holding dance materials.

For an excellent article on the papers of Canadian composers see:

- LaFrance, Cheryl. “Choreographers’ Archives: Three Case Studies in Legacy Preservation.” Dance Chronicle - Studies in Dance and the Related Arts 34, no. 1 (2011): 48–76.

Image and video attribution

- (1914). “Rose Theatre Orchestra – Regina 1914.” Retrieved April 2, 2013 from http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rose_Theatre_Orchestra_--_Regina_1914.jpg. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

- (1906). “Collège Sacré-Coeur Don Quichotte et les petits meuniers 1906.” Retrieved April 2, 2013 from http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Collège_Sacré-Coeur_Don_Quichotte_et_les_petits_meuniers_1906.jpg. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

- Van Vechten, Carl. (1956). “Melissa Hayden by Van Vechten.” Retrieved April 2, 2013 from http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Melissa_Hayden_by_Van_Vechten.jpg. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

- Roseborough & Rice. (1946). “Backstage photographs of Sir Ernest MacMillan (1946).” Retrieved April 2, 2013 from http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Backstage_photographs_of_Sir_Ernest_MacMillan_(1946).jpg. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

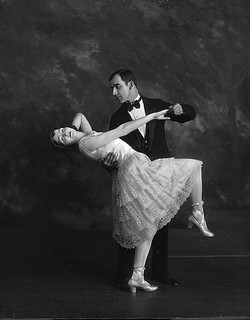

- Notman, Wm. & Son. (1928). “Mr. Vachon and dancing partner, Montreal, QC, 1928.” Retrieved April 2, 2013 from http://www.flickr.com/photos/museemccordmuseum/5348751649/. No known copyright restrictions.

- Lederman, John. (2011). “David Peregrine.” Retrieved April 2, 2013 from http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:David_Peregrine.jpg. CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0), via Wikimedia Commons.

- Tourisme Nouveau-Brunswick. (2011). “Pays de la Sagouine Noël 2011 a.” Retrieved April 2, 2013 from http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pays_de_la_Sagouine_Noël _2011_a.jpg. CC-BY-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), via Wikimedia Commons.

- Taylor, Robert. (2010). “Stratford Avon 2010.” Retrieved April 2, 2013 from http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Stratford_Avon_2010.jpg. CC-BY-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), via Wikimedia Commons.

- Karen Jamieson Dance. (2012). “‘Sisyphus’ 1983 Karen Jamieson Dance ” Retrieved April 2, 2013 from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qZ258osdAvI.

References

- ↑ Gary J. Chaffee, “Preserving Transience: Ballet and Modern Dance Archives,” Libri: International Journal of Libraries & Information Services 61, no. 2 (June 2011): 125.

- ↑ Richard Stone, “The Show Goes On! Preserving Performing Arts Ephemera, or the Power of the Program,” Art Libraries Journal 25, no. 2 (2000): 31.

- ↑ Chaffee, “Preserving Transience,” 125.

- ↑ Chaffee, “Preserving Transience,” 126.

- ↑ Ibid., 125.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Stone, “The Show Goes On!,” 31.

- ↑ Leslie Hansen Kopp, ed., Dance Archives: A Practical Manual for Documenting and Preserving the Ephemeral Art (Lee, MA: Preserve, 1995), 2 Getting Started.

- ↑ Ibid., 1 General Preservation.

- ↑ Chaffee, “Preserving Transience,” 125.

- ↑ Stone, “The Show Goes On!,” 32.

- ↑ Chaffee, “Preserving Transience,” 127.

- ↑ Stone, “The Show Goes On!,” 32.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Chaffee, “Preserving Transience,” 128.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Stone, “The Show Goes On!,” 31.

- ↑ David Farneth, “Valuing Composer’s Archives: How One Institution Encourages International Study, Performance, and Publication,” in Their Championship Seasons: Acquiring, Processing, and Using Performing Arts Archives, ed. Kevin Winkler (New York: Theatre Library Association, 2001), 125.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid., 126-127.

- ↑ Ibid., 127.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid., 128.

- ↑ Ibid., 128-29.

- ↑ Ibid., 129.

- ↑ Ibid., 130.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid., 132.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid., 134.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid., 135.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Kopp, Dance Archives, 1 General Preservation.

- ↑ Kathryn Harvey, “Tangible Archives of the Intangible, or Archiving the Ineluctable Modality of the Theatrical,” Canadian Theatre Review 150 (2012): 61-62.

- ↑ Chaffee, “Preserving Transience,” 128-129.

- ↑ Ibid., 126.

- ↑ Ibid., 127.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid., 125.

- ↑ Ibid., 126.

- ↑ Kopp, Dance Archives, 1 Preface.

- ↑ Ellen Ellis and New Zealand Theatre Archive, Caring for Your Theatre Archives. (Wellington, N.Z.: New Zealand Theatre Archives, 2005).

- ↑ Kopp, Dance Archives, 1 General Preservation.

- ↑ Ibid., 7 Documents on Paper.

- ↑ Ibid., 5 Photographs.

- ↑ Chaffee, “Preserving Transience,” 129.

- ↑ Kopp, Dance Archives, 5 Videotape and Film.

- ↑ Ibid., 1 General Preservation.

- ↑ Ibid., 5 Videotape and Film.

- ↑ Ibid., 4 Videotape and Film.

- ↑ Chaffee, “Preserving Transience,” 129.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Linda Tadic, “Towards a Digital Code of Hammurabi,” in Performance Documentation and Preservation in an Online Environment, ed. Kenneth Schlesinger, Pamela Bloom, and Ann Ferguson (New York, N.Y.: Theatre Library Association, 2004), 10.

- ↑ Ibid., 11.

- ↑ Harvey, “Tangible Archives of the Intangible,” 63.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Linda B Fairtile, “Performing Arts Manuscript Collections: Balancing Access and Privacy,” in Their Championship Seasons: Acquiring, Processing, and Using Performing Arts Archives, ed. Kevin Winkler (New York: Theatre Library Association, 2001), 5.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid., 6.

- ↑ Ibid., 10.

- ↑ Sarah Jones, Daisy Abbott, and Seamus Ross, “Redefining the Performing Arts Archive,” Archival Science 9, no. 3–4 (2009): 166.

- ↑ Ibid., 167.

- ↑ Ibid., 165.

- ↑ Ibid., 168.

- ↑ Ibid., 169.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid., 169-170.

- ↑ Matthew Reason, Documentation, Disappearance and the Representation of Live Performance (Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire; New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), 53.

- ↑ Francesca Marini, “Archivists, Librarians, and Theatre Research,” Archivaria no. 63 (Spring 2007): 31–32.

- ↑ Ibid., 32.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid., 8–10.

- ↑ Ibid., 26.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid., 29.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Kathryn Harvey and Michael Moosberger, “Theatre archives’ outreach and core archival functions.,” Archivaria no. 63 (2007): 37.

- ↑ Ibid., 38.

- ↑ Ibid., 39.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid., 39-40.

- ↑ Ibid., 40.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid., 41.

- ↑ Ibid., 43.

- ↑ Ibid., 50.

- ↑ Ibid., 44.

- ↑ Ibid., 45.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid., 46.

- ↑ Ibid., 47.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Francesca Marini, “Scenic Design and Archiving at the Stratford Shakespeare Festival,” Performing Arts Resources 29 (November 2012): 113–120.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Amy Bowring, “Dance Collection Danse: Canada’s Largest Archive and Research Center for Theatrica Dance History,” Dance Chronicle 34, no. 2 (2011): 276.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid., 279.

- ↑ Ibid., 279-80.

- ↑ Ibid., 280.

- ↑ Ibid., 283.

- ↑ Ibid., 285.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid., 284.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid., 285.

- ↑ Ibid., 284-85.

- ↑ Ibid., 283.

- ↑ “Dance Collection Danse, Archives, Publishing, Research and Education,” Dance Collection Danse, accessed April 12, 2013, http://www.dcd.ca/.

- ↑ “Booking a Research Appointment,” Dance Collection Danse, accessed April 12, 2013, http://www.dcd.ca/general/researchbook.html.

- ↑ “DCD Services,” Dance Collection Danse, accessed April 12, 2013, http://www.dcd.ca/general/dcdservices.html.

- ↑ Bowring, “Dance Collection Danse,” 283.

- ↑ “Performing Arts Resources,” Theatre Library Association, accessed April 12, 2013, http://www.tla-online.org/publications/par.html.