Course:ARCL140 Summer2020/TermProject Group9

EXPANSION OF HOMO SAPIENS

CONTRIBUTORS & ROLES

Tiffany Ma: Site1

Alyson Young: Site2

Simon Paul: Site3

Izzak Kelly: Site4

MAP

<iframe src="https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/embed?mid=1Jb9AnX16qXz-ECvH7aDv4u7qhwOlDP82" width="640" height="480"></iframe>

Introduction

The past two weeks of our lectures have been focusing on the origin, dispersal, and expansion of early Homo Sapiens. We find this topic specially intriguing - Finally!! After a great 70mya trek from the Paleocene primates in Chp7, alas we have arrived to our own species! After our class on 11/6, after we saw the map of Homo Sapiens' pattern of movement, we find ourselves wondering: How did our species manage expand to rapidly, especially when compared to earlier Hominin like Homo Erectus? We also noticed the temporal and spatial overlapping between Homo Sapiens and other Homos like Neanderthals, Denisovans, and Homo Erectus from around 100-40kya. We wonder how the early Homo Sapiens interacted with these neighboring species. This is how we decided to investigate on this topic.

Our textbook introduced three major models concerning the expansion of Homo Sapiens: 1)Out of Africa Model 2)Multi-regional Model 3)Assimilation Model. It also provides a neat timeline with corresponding maps illustrating the phased expansion: 1)Origin in Africa 2)Middle East and Asia 3)Australia 4)Europe 5)Americas. This is how we decided to arrange these four sites specifically, first Africa to last the Americas, with the intention to trace the expansion of Homo Sapiens chronologically.

However, as we began looking into the literature, it becomes apparent that the chronological timeline is not that cut and dry. This is still considerable debate in the scholarship. First, on the origin of Homo Sapiens. Rather than a definitive single origin, evidence suggests that Homo Sapiens originated within strongly subdivided populations all across Africa[1]. This concept is called "African multi-regionalism"[1]. Second, though most recent literature have sided with the Assimilation model over the others [2] [3], subsequent modifications and refinements have led to confusions over each of definitions[4]. A 2001 paper by Chris Stringer clarifies the four most common models: 1)African Replacement Model 2)African Hybridization and Replacement Model 3)Assimilation Model 4)Multiregional Model[4]. The four models disagree on the direction of gene flow. Another 2015 paper by Groucett et al flushes out more specific models concerning the dates when Homo Sapiens first stepped out of Africa. Ranging from 130-50kya, the earliest is from the Jebel Faya model, and the most recent is from the Upper Paleolithic model[5]. This paper suggests that both interior savannahs dispersal routes and coastal routes were used[5]. It also observes that several sites in the levant and South Asian have features of occupational hiatus[5], which suggests that initial expansions might not be successful.

For this project, we followed the broad expansion route of Africa --> Asia --> Europe --> South America. For each of the continents we have selected one corresponding site to report on: Jebel Irhoud for Africa, Zhouhoudian Cave for Asia, The Cave of Bones for Romania, and Monte Verde for South America. We each will focus on what the artefacts could tell us about the contemporary Homo Sapiens morphology, stone tool use, controlled use of fire, symbolic behavior, climate, and diet. First we bring you to Jebel Irhoud, Africa.

SITE 1: Jebel Irhoud, Africa

AUTHOR: Tiffany Ma

LOCATION: 50 km south-east of Safi in Morocco, Africa ; 31.8549, -8.8725

AGE: 315 ± 34 kya

Context

Jebel Irhoud is located northwest Africa. Today, much of the covering rock and sediments have been removed by the initial excavation back in 1960, but when it was first occupied by the early humans, it would have been a cave. The 315kya date would have situated the site in the Middle Pleistocene age, where the world was experiencing extreme climate upheaval - the alternating of glacial and interglacial periods. The 315kya date also suggests that the habitants of Jebel Irhoud would have overlapped temporally, and potentially spatial, with Homo Erecrtus(1.8mya-200kya).

History

In 1960, the Jebel Irhoud cave was first exposed from a mining operation. Subsequent excavations were made in the 1960s, where an almost complete skull(Irhoud1), an adult braincase(Irhoud2), an immature mandible(Irhoud3), and many others were excavated[6]. Initially, these fossils were dated to around 40kya, and were therefore identified as an African form of Neanderthal. Later, the date was slightly pushed back to 160 ± 16kya, when a tooth fragment was dated using U-series(US)/ESR[6].

In 2004, new excavations were initiated, and the search concluded in 2007. This time, though the deposits were poorly stratified, they were able to distinguish 7 different layers[6]. Layer1-6 yielded little fossils, but it was layer7 that contained the many famous adult skull(Irhoud10) and a nearly complete adult mandible(Irhoud11). Instead of relying on U-series(US)/ESR dating of samples from uncertain stratigraphy like before, the team used thermoluminescence dating on the heated flint artefacts. A total of 14ages were obtained for layer7, and the weighted average was taken as 315 ± 34 kya[6].

Relevance

The discoveries in Jebel Irhoud contributed significantly to our understanding of Homo Sapien evolution

First, by examining the fossils morphology, it became apparent that traits do not all evolve at the same time, that it is a mosaic process. In general, Jebel Irhoud fossils had derived Homo Sapien-like facial, mandibular, and dental structures, while their neurocranial and endocranial structures still retains primitive characteristics[7]. Compared to Neanderthals, these fossils suggest a shorter and retracted face, a weak brow ridge, a decreased mandible, as well as reduced post-canine teeth[7]. However, like Neanderthals, their braincase and endocast are elongated and not globular, resulting in a low occipital squama like that of Neanderthals' occipital bun. These observations supports our speculations that teeth evolved first before the brain size.

Second, by examining the stone tools and faunal remains, we were able to reconstruct the Middle Stone Age(300-40kya) industry. Occurrence of heated lithics and combustion indicate controlled use of fire. As for the fauna remains are mainly comprised of gazelle, Equidae, Alcelaphini, and all sorts of carnivores. Add on to those evidence of burnt bones, percussion notches for marrow extractions, and cuts on animal bones[6], it is apparent that the Jebel Irhoud community did consume hunting or scavenging - or both. Interestingly, some regions that are separated geographically today share some faunal similarities. This suggest that those two regions might be geographically linked at one point, possibly by land bridges during the glacial periods. The material culture also offers us glimpses into their stone tool use. Jebel Irhoud is dominated by Levallois technology with a high proportion of pointed retouched tools[6]. However, as is speculated, no Acheulean elements are present.

Priori to the breakthrough in 2007, the earliest Homo Sapiens were thought to have been dated to 195kya, from the site in Omo Valley Ethiopia. Now with Jebel Irhoud, the origin of Homo Sapiens is pushed further back by over 115 years. This raises a lot of questions in paleoanthropology: How do we classify the Jebel Irhoud fossils? Should we classify them as "anatomically modern humans"? Or should we still regard them as "archaic humans"? Or something in between? In his 2016 article, Chris Stringer identified four big questions concerning the origin of Homo Sapiens: 1)The diagnosis of Homo Sapiens 2)Mode of evolution 3)LCA of the Sapiens and Neanderthal lineages 4)Descendants of early Homo[8]. Questions are also being raised concerning gene flow between Homo Sapiens and other contemporary Homo, as well as the complex puzzle of the pan-African evolution process before 300kya.

Site 2: Zhoukoudian Cave, China

Author: Alyson Young

Location: China, Beijing, Fangshan District, 39 °41 ', 115 °51'

Age: 120kya - 80kya

Context

The Zhoukoudian Cave in Beijing, China is an essential find to Archaeologists.[9] In this cave, both Homo Erectus and Homo sapien remains were found.[9] Three crania that fit the modern Homo sapien set of traits were found, which are more globular than archaic humans.[9] When comparing these crania to the cranial measurements of other past and present populations, no connection was found with modern East Asian crania.[9] This shows that the variation in humans was vaster than it is today.[9]

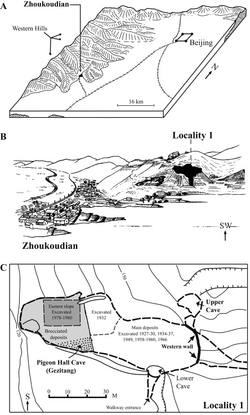

History

The Zhoukoudian cave system in Northern China was first investigated by geologist J. Gunnar Andersson in 1919.[10] Andersson recovered three isolated hominid teeth during these years, and they were later announced in 1926 and 1952 (Black, 1926;Zdansky, 1927; Weidenreich, 1937).[10] The excavation at Locality 1 (Figure 1) continued yearly throughout 1928 to 1937.[10] The field direction began under the supervision of Zhongjian Yang in the early years, and Wengzhong Pei (W.C. Pei) and Lanpo Jia (L.P. Chia) in the later years.[10] Homo erectus Skull I and a number of mandibular and dental remains were discovered in 1928, and Skulls II and III were discovered in 1929.[10] A turning point in the investigation of the site was the recovery of a well-preserved Skull III by Wengzhong Pei, which in turn continued to ensure the funding of the excavation.[10]

Pei and Zhang (1985) did note an apparent clustering of artifacts on the eastern edge of the “ash” level of Layer 8/9 near Locus G (Fig. 2).[10] This suggests that this may have been a focal point of hominid activity near the presumed eastern cave entrance where natural light would have been available.[10] Abundant stone tools in Locus K, also near the eastern side of the cave, tend to support this hypothesis.[10]

Original investigators noted that in layers 10 and 4 of the cave, the presence of “the evidently burnt condition of many of the bones, antlers, horn cores and pieces of wood found in the cultural layers, [and] a direct and careful chemical test of several speciments has established the presence of free carbon in the blackened fossils and earth.[11] The vivid yellow and red hues of the banded clays constantly associated with the black layers is also due to heating or baking of the cave’s sediments."[11]

Hyenas

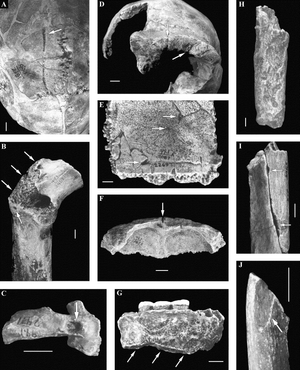

The fossils found in the Zhoukoudian cave show that out of the 42 hominid non-dental skeletal elements, 28 (or 67%) of the fossils have indirect and direct evidence of bite marks.[10] The fracture patterns are likely made by a large carnivore, showing gnawing, chewing, puncture marks, and regurgitation.[10] These marks are likely made by hyenas.

Weidenreich (1935: 453) initially believed that “transportation [of the hominid bones] … by beasts of prey is impossible. In the latter case traces of biting and gnawing ought to have been visible on the human bones, which is not the case”.[10] However, after the publication of Zapfe's (1939) paper, Weidenreich, 1941, Weidenreich, 1943 attributed damage on several Homo erectus fossils to mammalian carnivores, probably hyenas.[10]

An alternative to hyenas is the theory provided by Weidenreich, 1943 who theorized that the damage to the bases of the hominid skulls was the result of cannibalistic activity, but other sources find no such evidence.[10] The evidence to support the hyena theory shows that the facial skeletons are missing or fragmented on most skulls and the foramina magna have been enlarged.[10] The breakage patterns on the skull base are bite marks that large carnivores may make on their prey in order to open the skull vault and access the brain, which is an important part of the carcass to hyenas.[10]

Evidence of Fire

Original investigators noted that in layers 10 and 4 of the cave, the presence of “the evidently burnt condition of many of the bones, antlers, horn cores and pieces of wood found in the cultural layers, [and] a direct and careful chemical test of several speciments has established the presence of free carbon in the blackened fossils and earth.[11] The vivid yellow and red hues of the banded clays constantly associated with the black layers is also due to heating or baking of the cave’s sediments.”[11]

After the insoluble residues were extracted from the black bones through a dissolution of the carbonated apatite by 1N hydrochloric acid and 40% hydrofluoric acid, it was able to be detected using infrared spectra that the insoluble residues were characteristics of the burned bones.[11]

The majority of the remaining bones were yellow with speckled black surface colouration, and none of the bones from the upper part were turquoise.[11] Through experimentation, the bones from Locality 1 (white to yellow coloured) were heated to temperatures between 400 and 800 C for 2 hours.[11] These fresh bones turned black-grey in these conditions, and the black fossil bones from Layer 10 turned turquoise.[11] This further supports the hypothesis of the presence of fire, as the turquoise bones found may have been rendered this way through heat.

The strongest evidence for fire can be found in Layer 10, where the presence of burned macrofaunal bones can be found. Layer 10 also contains stone artifacts made mainly of quartzite.[11] Several quartzite pieces were observed during the examination, and all pieces came from the upper section.[11] It may be concluded that there is a close association of the artifacts and the burned bones.[11] 2.5% of the macrofaunal bones were burned, compared to the 12% of macrofaunal bones.[11] These percentages are similar to the values obtained in younger caves where fire was undoubtedly used by early humans.[11] Due to some of the sediments in Layer 10 being deposited under water, it is uncertain whether or not this is the original discard location of these bones.[11]

Additionally, there is a close association of artifacts and macrofaunal bones in the base of Layer 4, including many burned black bones.[11] These sediments were similarly laminated and deposited under water in a low energy environment, therefore the ash minerals were unable to be identified.[11]

Relevance

The relevance of the Zhoukoudian cave is that it provides evidence to various hypotheses. The charred bones found in this cave provide evidence to early hominins use of fire, giving researchers an idea of how early fire usage began. Additionally, bones being found so deep in the cave indicate two things: the first being that hyenas were prone to eating humans and perhaps transporting the bones to these locations, and secondly, the possibility of human burial. Finding bones so deep in the cave aid in hypothesizing about cultural norms of early hominins and how they may have rid themselves of their dead.

SITE 3: The Cave of Bones (Pestera Cu Oase), Romania

Author: Simon Paul

Location: The Cave of Bones in Romania is located circa 487 KM East of Bucharest by car. The nearest city is Anina in the Caras-Severin county, southwestern Romania. The coordinates for The Cave of Bones are 45.0167° N, 21.8333° E.

Age: The geological age of the site is estimated to be 34,000 - 36,000 14C years before present.

Context:

The Cave of Bones is a system of 12 karstic galleries and chambers, located in the Caras-Severin county in southwestern Romania. Karst is a topography composed of limestone, dolomite and gypsum which characteristically contains an underground draining system with caves, sinkholes, ravines and streams. The site is part of a 8,514 km squared region, situated in the third largest county, where the Danube river enters Romania. During the last Ice Age the Danube river formed the “Iron Gates”, a deep and long gorge stretched across the Southern Carpathian mountains, currently separating Romania and Serbia, forming a corridor for early humans moving back and forth between the plains of Central Europe and the Black Sea. Combining the fish rich Danube river with lush forested mountains, such as the Southern Carpathian mountain range and the Banat mountains, the early humans were assured of a variety of reliable food and water resources. A jawbone found in The Cave of Bones is dated to be between 34,000 - 36,000 14C years before present (years old). Other remains, a temporal bone, a partial brain case, and a facial skeleton, were found in 2003 and undergoing analysis.

History:

The site was discovered in 2002 by a speleological team exploring the karstic system of the Minis Valley in the Carpathian mountains near Anina city. They revealed a previously unknown chamber with an abundance of mammalian skeletal remains from bears, wolves, goats and other animals. The cave was originally thought to be a cave bear hibernation den, until they discovered unusual arrangements of remains raised on top of rocks, suggesting some level of human involvement. The human remains may represent some of the earliest humans to live in present day Europe, placing the specimens in a period where Neandertals and early modern humans could have interacted, the possibility of interbreeding presents itself. "Most of their anatomical characteristics are similar to those of other early modern humans found at sites in Africa, in the Middle East and later in Europe, but certain features, such as the unusual molar size and proportions, indicate their archaic human origins and a possible Neandertal connection." (Fitzpatrick 2020)

Relevance:

The remains of early humans found in the cave confirms that humans moved from Africa to other continents, such as Europe. This relates to the wider topic of human evolution documenting past human activities, how they survived and how they lived within their environments. Although the cave was primarily a bear hibernation den, the possibility is raised that the cave was "used as a mortuary cave for the ritual disposal of human bodies." (Fitzpatrick 2020) The site's location and restriction ensured preservation for tens of millennia - one is required to scuba dive to access the galleries with the fossils. "Their field work has produced one of the best dated and best documented cave bear sites in Europe, and an abundance of data for the past climates of the region." (Archaeology 2020)

References:

Yirka, Bob. 2020. "Analysis Of Bones Found In Romania Offer Evidence Of Human And Neanderthal Interbreeding In Europe". Phys.Org. https://phys.org/news/2015-05-analysis-bones-romania-evidence-human.html.

Fitzpatrick, Tony. 2020. "Earliest Modern Humans In Europe Found | The Source | Washington University In St. Louis". The Source. https://source.wustl.edu/2003/09/earliest-modern-humans-in-europe-found/.

Gibbons, Ann. 2020. "Oldest Homo Sapiens In Europe—And A Cave Bear Pendant—Suggest Cultural Link To Neanderthals". Science | AAAS. https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/05/oldest-homo-sapiens-europe-and-cave-bear-pendant-suggest-cultural-link-neanderthals.

Archaeology, Current. 2020. "Oase Cave: The Discovery Of Europe's Oldest Modern Humans - World Archaeology". World Archaeology. https://www.world-archaeology.com/features/oase-cavethe-discovery-of-europes-oldest-modern-humans/.

Site 4: Monte Verde, Chilé

Author: Izzak Kelly

Location: Monte Verde, Chilé (Lat: -41.5028 Lng: -73.2027)

Age: ~14,500 years cal BP.

Context:

Located near Puerto Montt in Southern Chile, Monte Verde has been a site seen to have the potential to “further our understanding of the first peopling of the Americas” [12] with “new evidence of stone artifacts, faunal remains, and burned areas suggests discrete horizons of ephemeral human activity” [12] being a few things found within the area and its surroundings. The site is able to sustain life, possessing a coastal landscape it also boasts a coastal migration model. As for its environment, “a forested area of south-central Chile”[13] is what encompasses the site. The “archaeological levels of the Monte Verde site are exposed at 50 m a.s.1” [13] in the “small, one m high cutbanks of the Chinchihuapi Creek, 30 km southeast of Puerto Montt”, 15 km from the Maullin River.[13]

History:

“Dated between at least ~18,500 and 14,500 cal BP” [12], Monte Verde was uncovered in 1976 during excavations led by archaeologist Tom Dillehay. Additionally, radiocarbon dating displayed signs of human inhabitants. In the initial excavation, many small hearths were discovered, in addition to two larger sized ones. Local animal remains wooden posts and hide clothing scraps are some of the artifacts that were unearthed. Other discoveries included “ a heterogeneous stone tool assemblage representing three technologies: selectively collected, naturally fractured, and culturally utilized stones with one or more sharp, usable edges; unifacially and bifacially flaked tools; and pecked-ground bola and grinding stones”.[13]

Relevance:

Physical specimens gathered at Monte Verde have prompted some archaeologists to question the previously established opinions on the Americas’ earliest inhabitants. “Characterized by bone and stone technologies, and by well-preserved wood artifacts, dwelling foundations of both earth and wood, and abundant remains of useful plants”[14], after radiocarbon dating was done, Monte Verde began to be known as the oldest-known site of human habitation in the Americas.

The coastal migration hypothesis, which is believed to have had an effect in Monte Verde argues that people migrated from Asia toward the coasts of North and South America. Monte Verde is approx. 8,000 miles south of the Bering Strait, meaning that in order to get from point to point the distance would need to be closed on foot, a fairly unreasonable task. One of the most groundbreaking discoveries was that Monte Verde lacked Clovis points, distinctive stone tools found dating to roughly 13,000 years ago. Through much of the 20th century, many archaeologists supported “Clovis First” a hypothesis stating that those who made these artifacts were the first inhabitants of the Americas. Reports of older pre-Clovis sites were dogmatically dismissed on the grounds that they had either been incorrectly excavated or improperly dated. However, being very well-preserved, carefully excavated, and analyzed with state-of-the-art methods and tools. Eventually, the archaeological community decided that non-Clovis peoples reached South America by at least 14,000 years ago. Since then there has been a numerous amount of pre-Clovis sites between 13,300 and around 15,000 years old. North America being home to about 10 of them.

Conclusion:

In our project we have researched four locations around the world of early human expansion from Africa. We have researched a location in Africa, Europe, Asia, and south America. We explore the region early humans lived in, how they lived, what they did to survive. A common theme with our research locations is the suitability of each region, in regards to shelter, food and water, etc. Each location was in a safe area, such as a cave or cliff side, access to food and water was not a problem with the sites being in close distance to rivers and forests. An additional topic was the abundance of human remains, and tools, in the majority of our sites.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Scerri, Eleanor M.L.; et al. (2018). "Did Our Species Evolve in Subdivided Populations across Africa, and Why Does It Matter?". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 33: 582–594. Explicit use of et al. in:

|last=(help) - ↑ Smith, Fred H.; et al. (2005). "The assimilation model, modern human origins in Europe, and the extinction of Neandertals". Quaternary International. 137: 7–19. Explicit use of et al. in:

|last=(help) - ↑ Smith, Fred H.; et al. (2017). "The Assimilation Model of modern human origins in light of current genetic and genomic knowledge". Quaternary International. 450: 126–136. Explicit use of et al. in:

|last=(help) - ↑ 4.0 4.1 Stringer, Chris (2001). "Modern Human Origins—Distinguishing the Models". African Archaeological Review. 18: 67–75.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Groucutt, Huw S.; et al. (07/2015). "Rethinking the Dispersal of Homo Sapiens out of Africa". Evolutionary anthropology. 24: 149–164. Explicit use of et al. in:

|last=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Richter, D (2017). "The age of the hominin fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco, and the origins of the Middle Stone Age". Nature. 546: 293–296.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Hublin, J.; et al. (2017). "New fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco and the pan-African origin of Homo sapiens". Nature. 546: 289–292. Explicit use of et al. in:

|last=(help) - ↑ Stringer, Chris (2016). "The origin and evolution of Homo sapiens". Royal Society. 371.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 EXPLORATIONS: AN OPEN INVITATION TO BIOLOGICALANTHROPOLOGY, “Chp. 12,” in EXPLORATIONS: AN OPEN INVITATION TO BIOLOGICALANTHROPOLOGY, ed. Beth Shook et al., n.d., pp. 12-13.

- ↑ 10.00 10.01 10.02 10.03 10.04 10.05 10.06 10.07 10.08 10.09 10.10 10.11 10.12 10.13 10.14 10.15 10.16 Boaz, Noel T.; et al. (May 31 2002). "Mapping and taphonomic analysis of the Homo erectus loci at Locality 1 Zhoukoudian, China". Science Direct. Retrieved https://www-sciencedirect-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/science/article/pii/S0047248404000144?via%3Dihub#FIG1. Explicit use of et al. in:

|last=(help); Check date values in:|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ 11.00 11.01 11.02 11.03 11.04 11.05 11.06 11.07 11.08 11.09 11.10 11.11 11.12 11.13 11.14 11.15 Weiner, Steve; et al. (July 10 1998). "Evidence for the Use of Fire at Zhoukoudian, China". Jstor. Archived from the original on

|archive-url=requires|archive-date=(help). Explicit use of et al. in:|last=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Dillehay, Tom D., Carlos Ocampo, José Saavedra, Oliveira Sawakuchi Andre, Rodrigo M. Vega, Mario Pino, Michael B. Collins, et al. 2015. New archaeological evidence for an early human presence at monte verde, chile. PLoS One 10, (11) (11), http://ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/docview/1734277979?accountid=14656

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Pino, Mario & Dillehay, Tom. (1988). Monte Verde, South‐Central Chile: Stratigraphy, climate change, and human settlement. Geoarchaeology. 3. 177 - 191. 10.1002/gea.3340030302.

- ↑ Dillehay, T., Collins, M. Early cultural evidence from Monte Verde in Chile. Nature 332, 150–152 (1988). https://doi-org.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/10.1038/332150a0

Bibliography

Archaeology, Current. 2020. "Oase Cave: The Discovery Of Europe's Oldest Modern Humans - World Archaeology". World Archaeology. https://www.world-archaeology.com/features/oase-cavethe-discovery-of-europes-oldest-modern-humans/.

Dillehay, T., Collins, M. Early cultural evidence from Monte Verde in Chile. Nature 332, 150–152 (1988). https://doi-org.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/10.1038/332150a0

Dillehay, Tom D., Carlos Ocampo, José Saavedra, Oliveira Sawakuchi Andre, Rodrigo M. Vega, Mario Pino, Michael B. Collins, et al. 2015. New archaeological evidence for an early human presence at monte verde, chile. PLoS One 10, (11) (11), http://ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/docview/1734277979?accountid=14656 (accessed June 17, 2020).

EXPLORATIONS: AN OPEN INVITATION TO BIOLOGICALANTHROPOLOGY. “Chp. 12.” Essay. In EXPLORATIONS: AN OPEN INVITATION TO BIOLOGICALANTHROPOLOGY, edited by Beth Shook, Katie Nelson, Kelsie Aguilera, and Lara Braff, 12–13, n.d.

Fitzpatrick, Tony. 2020. "Earliest Modern Humans In Europe Found | The Source | Washington University In St. Louis". The Source. https://source.wustl.edu/2003/09/earliest-modern-humans-in-europe-found/.

Gibbons, Ann. 2020. "Oldest Homo Sapiens In Europe—And A Cave Bear Pendant—Suggest Cultural Link To Neanderthals". Science | AAAS. https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/05/oldest-homo-sapiens-europe-and-cave-bear-pendant-suggest-cultural-link-neanderthals.

Golubovic, Zagorka. 2020. Hrfd.Hr. http://www.hrfd.hr/documents/03-golubovic-pdf.pdf.

Hublin, Jean-Jacques, Abdelouahed Ben-Ncer, Shara E. Bailey, Sarah E. Freidline, Simon Neubauer, Matthew M. Skinner, Inga Bergmann, Adeline Le Cabec, Stefano Benazzi, Katerina Harvati, and Philipp Gunz. "New Fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco and the Pan-African Origin of Homo Sapiens." Nature 546, no. 7657 (2017): 289-92. doi:10.1038/nature22336.

Noel T. Boaz, Russell L. Ciochon, Qinqi Xu, Jinyi Liu. "Mapping and taphonomic analysis of the Homo erectus loci at Locality 1 Zhoukoudian, China." Journal of Human Evolution, p. 519-549, vol. 46, issue 5 (2004). Accessed June 18, 2020. https://www-sciencedirect-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/science/article/pii/S0047248404000144?via%3Dihub

Pino, Mario & Dillehay, Tom. (1988). Monte Verde, South‐Central Chile: Stratigraphy, climate change, and human settlement. Geoarchaeology. 3. 177 - 191. 10.1002/gea.3340030302.

Richter, Daniel, Rainer Grün, Renaud Joannes-Boyau, Teresa E. Steele, Fethi Amani, Mathieu Rué, Paul Fernandes, Jean-Paul Raynal, Denis Geraads, Abdelouahed Ben-Ncer, Jean-Jacques Hublin, and Shannon P. Mcpherron. "The Age of the Hominin Fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco, and the Origins of the Middle Stone Age." Nature 546, no. 7657 (2017): 293-96. doi:10.1038/nature22335.

Scerri, Eleanor M.l., Mark G. Thomas, Andrea Manica, Philipp Gunz, Jay T. Stock, Chris Stringer, Matt Grove, Huw S. Groucutt, Axel Timmermann, G. Philip Rightmire, Francesco D’Errico, Christian A. Tryon, Nick A. Drake, Alison S. Brooks, Robin W. Dennell, Richard Durbin, Brenna M. Henn, Julia Lee-Thorp, Peter Demenocal, Michael D. Petraglia, Jessica C. Thompson, Aylwyn Scally, and Lounès Chikhi. "Did Our Species Evolve in Subdivided Populations across Africa, and Why Does It Matter?" Trends in Ecology & Evolution 33, no. 8 (2018): 582-94. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2018.05.005.

Smith, Fred H., Ivor Janković, and Ivor Karavanić. "The Assimilation Model, Modern Human Origins in Europe, and the Extinction of Neandertals." Quaternary International 137, no. 1 (2005): 7-19. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2004.11.016.

Smith, Fred H., James C.m. Ahern, Ivor Janković, and Ivor Karavanić. "The Assimilation Model of Modern Human Origins in Light of Current Genetic and Genomic Knowledge." Quaternary International 450 (2017): 126-36. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2016.06.008.

Stringer, Chris. "Modern Human Origins—Distinguishing the Models." African Archaeological Review 18 (2001): 67-75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011079908461.

Stringer, Chris. "The Origin and Evolution of Homo Sapiens." Royal Society 371 (2016). doi:https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0237.

Weiner, Steve, Qinqi Xu, Paul Goldberg, Jinyi Liu, and Ofer Bar-Yosef. "Evidence for the Use of Fire at Zhoukoudian, China." Science 281, no. 5374 (1998): 251-53. Accessed June 18, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/2896019.