Advertisements and Feminism

Introduction

Feminism simply put, is the belief that women and men share equal rights and opportunities, under the means of political, social, and economic perspectives. Alternatively, it means that women have the right to enough information to make informed choices about their lives. Here, the term “women” is an encompassing term that includes poor black lesbians, rich white women, and middle-class straight Asian women; which given equal attention to every individual, regardless self-identification, socioeconomic status, and racial groups[1].

The acknowledgement of Feminism continues to be a heated debate in the contemporary society. While some people regard it as a belief of pursuing gender equality, some others argue that the term transmits a meaning of "man-hating" or even equating feminists to lesbians. Advertising companies see this as a chance to obtain attention and show interest in the emergence of a modern wave of feminism. Whether the campaigns' objective is to increase sales (obtain loyalty customers) or raising awareness about girl empowerment is for the public to decide.

Examples of feminist celebrities examples:[2]

- In January 2014, Beyoncé wrote an essay Gender Equality is a Myth! for the Shriver Report, an American feminist pressure group. It was neither long nor academic, but included statistics that proved, contrary to the sentiment of her 2011 hit Run the World (Girls), women were not in charge. “[Women] must demand that we all receive 100 per cent of the opportunities,” she wrote, a rallying cry that echoed through popular culture for the rest of the year.

- British actress and newly appointed UN Women Goodwill Ambassador Emma Watson addressed the UN in September and gave a speech in which she invited men and boys to “take up the mantle” of ending gender inequality. Actors including Russell Crowe, Benedict Cumberbatch and Ian McKellen pledged their support.

In 2013, singer and celebrity Miley Cyrus provocative and sexualized performance at the American Video Music Awards caused fellow musician Sinead O'Connor to write an open letter to Cyrus pleading for her to avoid engaging in further acts of sexualization and objectification[3]. However, feminist critics of MIley and O'Connor are divided in terms of whether or not Sineado O'Connor was engaging in "slut-shaming" or if Miley was simply engaging in a form of sexual empowerment and expression. According to Third-Wave Feminists, Miley's performance was an 'expression of her sexual liberation while O'Connor's letter prohibits Miley from control over her career"[4] Conversely, Second-Wave Feminists lauded O'Connor's letter noting how it heralded a call for the role of objectification and sexualization in music and how young female musicians must base their identity around the notion of sexual desirability[5]

Like all political movements, feminism needs a manifesto, of which We Should All Be Feminists is perhaps the latest chapter. But it also needs popular champions and role models, especially in our social media age. As the public understand the substantial impact from advertising, some companies (especially female products) shift their strategy to utilizing feminist ideas.

The Role of Advertisement

Our life is constantly bombarded by the influence of advertisement nowadays—it influences our purchasing decisions and ideas about certain goods and services. It is essentially a paid form of non-personal presentation or promotion of ideas by an identified sponsor with the goal to disseminate information around an idea, good or service. Nowadays it is hard to find any big-scale organizations that don’t choose advertisement as a mean to boost their sales. Many of them produce advertisements that trigger consumption motives upon consumers and make them believe that the functionality of a certain product. William J. Stanton clearly reveals the nature of the advertisement, “Advertising consists of all the activities involves in presenting to a group, a non-personal, oral or visual, openly sponsored message regarding disseminated through one or more media and is paid for by an identified sponsor”. Besides the function of boosting sales by generating trust among existing consumers and attracting potential consumers, advertisements are a tool for building brand loyalty and trust[6]. In a fierce competitive market, it is important for an organization to build their own brand image through advertisement. Once customers have developed brand loyalty, new-comers would experience the difficulties to earn popularities in the same market.

Advertisement in Gender Representation

While social media such as advertising has a profound socializing force, teenagers are exceptionally vulnerable to media teachings. The impact of advertising received unconsciously and teenagers’ lack of capacity to distinguish between reality and fantasy contribute to limitation of their development.

Impact on Women and Girls

Many research articles address the issue of misrepresentation of female characters in media. In mainstream media, the frequency of male image appears more than the frequency of female image; for those females do appear are often portrayed in stereotypical ways.

Gender Stereotypes

Advertising has a significant impact on children in perceiving gender roles. For instance, women have an ultimate responsibility for the household chores because products like laundry detergent, soap, and child care products target female audiences the most as if they are the only one in charge of doing household chores in the family. Conversely, men are expected to be the bread winners of the family, while women are relegated into the role of domestic servants. Hence, there is a double standard for women where they must balance work and family responsibilities.

Impact on Men and Boys

Maybe less of the society attention, male representation in social media is also associated with stereotyping. Boys are taught at a very young age that the gender of male means masculinity—the beliefs/behaviors that correspond to decisiveness, toughness, independence, even in some cases associate with aggression and violence. Males are expected to adhere to rigid forms of hypermasculinity, exacerbated by the male hegemonic attitudes of violence, aggression, and risk-taking behaviour[7]

Shallow and Incomplete Male

Some commercials depict males as superficial and shallow[8], for example, the beer commercials. It shows males as engaging in sophomoric pranks or actions in an effort to impress women. While some advertisement show the competence of male in some professional industries such as mechanics and engineering, they are generally depicted as incomplete in the household-related advertisement. In comparison, women have full control over this situation and know how to rectify the problem by using the advertised product.

Feminism in Advertisements

Sex role stereotyping in media content has been a major concern of feminist leaders who believe that media images have been partially responsible for creating and maintaining limited social roles for women[9]. Several major goals of the feminist movement have included (1) opening up all job categories to women, (2) compensation tied to job description, not to gender, (3) a more equal division of labor within the home, (4) less emphasis on the female as an “object” whose primary function is attracting the opposite sex, and (5) the right for each individual to develop to her full potential.

A new wave of advertising appeared in the market, targeting the female audiences, which claims to strengthen girl power and advocates Feminism. Those advertisements transmit powerful messages to viewers, especially young girls. However, such advertising campaign triggers a clear division of debut of whether it does any good for the girls, which still remains a question. Companies like Always, Pantene, Dove, and Verizon launched “fempowerment” campaigns have all recently realized that framing video ads around a girl-power sentiment helps them become viral hits. Writer Emily Shire said, the Always “Like a Girl” campaign demonstrates real problems—femaleness as a derogatory statement, decrease in self-confidence as women mature—in a beautiful and clear way, but then pretends a corporate manufacturer of panty liners meant to “help you feel fresh every day” can solve them[10].

Companies’ Fempowerment Campaigns

There are companies that employ feminist ideas in their product promotion as means to increase their customer loyalty and show the society that, they really care their customers. But who really benefit from this campaign? Here are some examples of advertising that transmit girl-empowering messages: [10].

Pantene: set up a Shine Strong fund, which will underwrite grants for the American Association of University of Women’s Campus Action Project as well as supporting the program’s operating costs for a total support amount of $121,000.

Dove’s financial contributions are a little tougher to track down, though they do appear to have been underwriting a handful of projects in partnership with the Boys & Girls Clubs of America, Girls Inc, and Girl Scouts.

Always doesn’t donate cash to any programs, but when I asked the company about backing up their “Like a Girl” campaign with programming, the sent back a statement about their “Puberty Education Program,” which provides free materials about puberty (and Always products) to schools.

Verizon, on the other hand, has stood out from the trend in a handful of ways. They’re the only company I spoke with that has actually paid to air their empowerment ad on television, and their website boasts technology innovation programs and awards in the millions of dollars, a significant chunk of which does indeed go to school-age girls.

Madeline Di Nonno, CEO of the Geena Davis Institute on Gender: For those of us who surround ourselves with intersectional anti-oppressive ideology, what’s considered progress in the mainstream can feel like a joke. But that’s our piece of the jigsaw—to be progressive is by definition to be ahead of the curve. While we don’t need to be naivel over-celebratory about billion-dollar conglomerates pandering to female consumers, I do get immense enjoyment from the fact that such companies are doing so, not because they want to, but because they have to.

“femvertising” is no longer a niche internet neologism, but a genuinely queasy chapter in feminism’s fourth wave, said Nosheen Iqbal (2015).

Plotted elsewhere on the graph would be Dove’s decade-old Real Beauty campaign, then considered revolutionary for selling body moisturiser – sorry, celebrating diversity in the female form – to all women. Later on, wising up to feminism “trending”, as it were, on social media, came cosmetic brand CoverGirl with #GirlsCan in February 2014. This campaign, said the company, was “about discovering, encouraging whatever it is that makes a girl take up the challenge; break those barriers and turn ‘can’t’ into ‘can’”. It was fronted, credibly, by Pink, Ellen DeGeneres and Janelle Monae. Which was almost enough to make you forget that CoverGirl spent 50 years telling young women “your personality needs layers, your face doesn’t”.[11]

Madeline Di Nonno, CEO of the Geena Davis Institute on Gender: For those of us who surround ourselves with intersectional anti-oppressive ideology, what’s considered progress in the mainstream can feel like a joke. But that’s our piece of the jigsaw—to be progressive is by definition to be ahead of the curve. While we don’t need to be naivel over-celebratory about billion-dollar conglomerates pandering to female consumers, I do get immense enjoyment from the fact that such companies are doing so, not because they want to, but because they have to.

Does Advertising Hijack Feminism?

Due to the popularity of the use of feminism ideas in the advertisements, a term "femvertising" appeared to describe the phenomenon: where the hard sell has been 'pinkwashed' and replaced by something resembling a social conscience, and where advertisers are falling over each other to climb on board the feminist bandwagon. [12]

So rather than objectifying women and selling them idealised versions of themselves, the advertisers are cottoning on to the idea that honesty sells too Last year, lifestyle website SheKnows surveyed more than 600 women about femvertising. A staggering 91 per cent believed that how women are portrayed in ads has a direct impact on girls' self-esteem, and 94 per cent said that depicting women as sex symbols is harmful.

The advertisers asked women and girls how they felt and - instead of feeding them back what they think they wanted - chose to portray what they'd been told: our deepest insecurities (some have criticised such ads for knocking women down so they can build them up again).

It smacked of a company adopting feminism because it seemed trendy; out of self interest. That’s where brands like Sport England and Always have got it right - they're turning the mirror back on us. The moment those women in the first #LikeAGirl ad understood they'd been fed a cliche about their own gender was powerful, regardless of the motive.

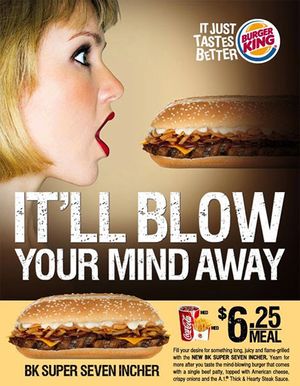

Ironic Sexism

Ironic SexismLink label is a term defined by Alissa Quart in New York Magazine. In the time of 2010s, which is during the second decade of post-feminism, researchers find that there is a gap of the impact result from ironic sexism appeared to aim at men and women. It draws on Barthes (1973) and Williamson (1978) employing in-depth semiotic analysis to “explore connotative meanings” extracting “what is 'hidden' beneath the 'obvious'” revealing “how the same text may generate different meanings for different readers” (Chandler 2002, p.215). The study asks whether such ‘ironic sexism’ in advertising, presented as simply ‘having a sense of humour about gender stereotypes’ is part of a wider and continuing backlash against feminism which has now paved the way simply for the return of a patriarchal gaze in advertising without the need, increasingly, to mask this with ‘knowing’ irony.[13]

References

- ↑ Manifesta: Young Women, feminism, and the Future, 2010 http://www.feminist.com/resources/artspeech/genwom/whatisfem.htm

- ↑ Vincent, Alice How feminism conquered pop culture 30 December 2014, The Telegraph http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/culturenews/11310119/feminism-pop-culture-2014.html

- ↑ Smith, Michelle. "Miley Cyrus, Sinéad O’Connor and the future of feminism." 7 October 2013.The Conversation https://theconversation.com/miley-cyrus-sinead-oconnor-and-the-future-of-feminism-18938

- ↑ Smith, Michelle. "Miley Cyrus, Sinéad O’Connor and the future of feminism." 7 October 2013.The Conversation https://theconversation.com/miley-cyrus-sinead-oconnor-and-the-future-of-feminism-18938

- ↑ Smith, Michelle. "Miley Cyrus, Sinéad O’Connor and the future of feminism." 7 October 2013.The Conversation https://theconversation.com/miley-cyrus-sinead-oconnor-and-the-future-of-feminism-18938

- ↑ Meaning, Definition, Objective and Functions of Advertising, 2015 http://www.publishyourarticles.net/knowledge-hub/business-studies/advertising/1028/

- ↑ Hardy, E. (2015). The female ‘apologetic’ behaviour within Canadian women’s rugby: athlete perceptions and media influences. Sport in Society, 18(2), 155-167.

- ↑ Types of Stereotyping in Advertising, 2016 http://smallbusiness.chron.com/types-stereotyping-advertising-11937.html

- ↑ Busby, L. J., and G. Leichty. "Feminism and Advertising in Traditional and Nontraditional Women's Magazines 1950s-1980s." Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 70.2 (1993): 247-64

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Is “Girl Power” Advertising Doing Any Good? Natalie Baker, 2014 https://bitchmedia.org/post/is-girl-power-advertising-doing-any-good

- ↑ Iqbal, Nosheen, Femvertising: How Brands are Selling Empowerment to Women. October, 2015 http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2015/oct/12/femvertising-branded-feminism

- ↑ Cohen, Claire. How advertising hijacked feminism. Big time. The Telegraph. July 2015. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/women/womens-life/11727478/How-advertising-hijacked-feminism.-Big-time.html

- ↑ Biloshmi, ana, Advertising in Post-Feminism: The Return of Sexism to Visual Culture? http://www.eacaeducation.eu/uploads/Thesis_Competition/Bachelor/Ana_Blloshmi/Essay_Ana_Biloshmi.pdf