Course:ANTH302A/2020/Maldives

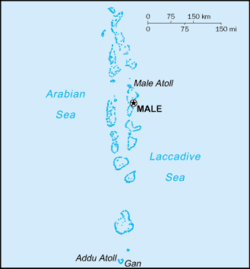

The Maldives[1] is a small island nation located in the region of Southern Asia with a population of 541 000 and density of 1802 people per km2 as of 2020. It is made up of 22 atolls, consisting of approximately 1200 islands, only about 200 which are inhabited [2]. The Maldives, have been credited for being the first South Asian country to provide electricity all across the nation, unfortunately this results in large expenditures on importing fossil fuels, as their main source of power.[3]

The economy is made up largely of tourism, fishing, and shipping. One of the world’s poorest 20 countries in the 80’s, the Maldives has undergone a complete transformation, with the aid of the world bank and other global organisations for development [4]. There seems to be a few different major issues in Maldives nowadays. First is the debt of approximately $100million owed to the IFC and IDA (to start), second is the environmental crisis, a third is the rising extremism in the area, and finally, with the impacts of Covid-19, there was a complete economic shutdown.

During the first wave of Covid-19, the Maldives was effected very little (5,300, including 21 deaths), however, recently transmission of the virus has rapidly increased across the atolls [5]. As of August 7th, 2020, it is reported that the Maldives cases increase by more than "100 daily virus cases per million people compared to the United States" [6]. Being such a small developing island nation, the heath care system has not been prepared to deal with a pandemic and with fast rising case numbers it is unlikely the system will be able to cope.

The Maldives is a member of the Commonwealth of Nations, having achieved their Independence from the United Kingdom in 1965[7]. The Country has recently seen a period of civil unrest and has taken steps toward democratic reform[8].

Social Protection Programs and Emergency Preparedness - Riana

The Maldives is a nation that is heavily reliant on its tourism industry, which accounts for two thirds of the nations GDP [9]. In the age of the coronavirus, thousands were put out of work, including the large population of migrant workers that come to the country specifically to work in the booming tourist industry. In order to provide adequate resources, PPE, and care to its residents and workers, the government had to reach out for external funding from many sources, including the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. These two groups gave millions of dollars in efforts to equip the country's health care workers, provide relief to people in lower socioeconomic classes, and help to build a social protection program for emergencies in the future[9] [10].

As with many countries in the world, citizens and government only became realistically aware of their lack of preparedness once an emergency situation arose. The virus spread quickly across congested cities in the archipelago nation and required a shutdown when nearly “30 percent of the country’s population” was threatened [9]. Although the government acted swiftly, it became quickly clear how ill prepared they were for a public health emergency [9]. Several nurses on the front line noted the lack of adequate PPE in the country and difficulty in dispersing it across the many less populated islands while many poor migrant workers were also displaced and much more likely to transmit the disease [9]. One of the main goals with the influx of money is to create social protection programs that aid citizens should another emergency arise. Other South Asian countries, such as Nepal, developed methods of emergency preparedness in the past in response to natural disasters that continue to help their citizens in a pandemic, such as “rapidly setting up disbursement authorities and channels” [12]. The country learned through the 2015 earthquake that funds needed to be readily available and not heavily taxed by banks so that the citizens that require it are able to access it quickly and efficiently[12]. One of the main goals from the World Bank $12.8 million dollar emergency income support project is to provide low income families with approximately $322 per month to mitigate the economic impact of COVID-19, a plan that could be enacted in the future as well should another emergency occur [13]. Indeed, a social protection program could also help keep track of residents and monitor their safety and wellbeing across the uniquely difficult geographic layout of the Maldives to determine where to send emergency support and resources. This would be especially useful in a country that has a significant amount of migrant labourers that are often the most marginalized and overlooked in times of crisis[14].

When thinking about building safety nets and protective programs, it is important to think about allocation of funding and who is making the decisions about funding. The money that the Maldives has received during the pandemic has been from international sources that likely do not have an in-depth understanding of the complications facing the country. In a country like Nepal that has had to make decisions about distributing funds post emergency situations, a few things have been made clear and should be thought about in the context of the Maldives as well. When looking to rebuild their country, residents of Nepal noted that “many on the ground see the agendas of international agencies or urban elites dominating the immediate concerns of rural residents” [15]. It is reasonable to assume that high level conversations such as this are responsible for policies that are intended to help but actually further marginalize those already of lower socioeconomic status, such as taxing conditions on borrowers that prevent them from accessing government subsidized loans [12]. In order to create an effective protection plan that truly seeks to help the citizens that need it most, you have to work in “close engagement with people living in specific terrain” to understand which services are needed and when [14]. The Maldives has had issues with debt in the past to countries such as China, struggling to pay them back and crediting it to lack of coordination and organization on the part of the Maldivian government, showing once again that government and other high level officials are not always the best decision makers when it comes to allocating funds efficiently [16]. Concerns have been raised by residents for a long time about the economic state of the country, all revolving around the fact that "the overall level of indebtedness is high and reserves coverage is low", so it is imperative that the country handles this new influx of funds responsibly[17]. This is a real opportunity for the country to assess and even out their socioceonomic and income disparities while also possibly moving towards paying back their debt [17]. Looking back to Nepal in 2015, their slow response to the emergency was also due to governmental instability and further strengthens the point that “past disasters demonstrate the importance of not allowing foreign actors to control the process of rebuilding” [15].

What I seek to highlight here is the importance of holistic and careful consideration when allocating funds across this complex archipelago nation. The country thrives and relies on tourism for economic success and stability but needs a plan in place should this not be possible to carry out, as it has been during the COVID-19 pandemic. If there is anything we have learned from this pandemic, it is that countries that have successful health care systems, stimulus packages, and an overall emergency preparedness plan are most successful in fighting the virus, such as Singapore and South Korea, two countries that learned from previous epidemics and were therefore more prepared for COVID-19 [18]. A well thought out and agreed upon social protection program would allow the Maldives to respond quickly to keep their citizens safe and healthy.

Health Care System During a Pandemic - Avril

According to WHO, the Maldives only contain 10 hospitals spread over its 200 inhabited islands, culminating in a mere total of 470 hospital beds (1 bed to 577 people) [19]. Such limited medical infrastructure in normal times could easily put stress on a health care system, but during a worldwide world wide pandemic could spell chaos for such a system. As of August 19th, 2020, the total number of Covid-19 cases for the Maldives was 6,079, with 2,407 active cases and 144 hospitalized - 170 new cases than the day previous[20]. Such numbers may seem small in comparison to countries like the USA or Brazil but in comparison to cases per capita (which better compares countries numbers when the population differences are drastic) the Maldives held the highest rate in the world as of early August[21]. There may only be 144 hospitalized cases of Covid-19 as of August 19, 2020, but that still makes up 31% of hospital beds in the country occupied - that is without taking into account other non-Covid related hospitalizations and other medical emergencies. With cases of the virus on the rise in the Maldives, the abilities of its healthcare system are in questionable times.

The Maldives capital city, Malé, is a densely populated urban area containing approximately 28% of the country's population in just 6.8 km², has been the epicentre for the pandemic in the country. Especially at the start of the pandemic, obtaining proper and mass amounts of Personal Protection Equipment (PPE) was vital to stop the spread of Covid-19 while protecting Health Care workers, however, was difficult for a small island nation to obtain while the entire rushed to get the same supplies. In June of 2020, the World Bank gave the Maldives a 7.3 million to help obtain critical PPE and medical supplies, improve intensive care facilities, increase daily testing limits at the countries labs, and give specific Covid-19 training for medical staff who treat positive tested patients[22]. The funding from the World Bank is also reportedly going to support community efforts and awareness to stop the spread of the virus, mainly targeted at Malé due to its high population density. Even more funding to support the Maldives Health Care system has been made available by the World Bank through it's "$10 million contingency financing, under Disaster Risk Management Development Policy Financing with a Catastrophe Deferred Drawdown Option (CAT DDO)" [23]. All such funding for the country's health care system is not only hoped to greatly help with the pandemic care but build a better future health care system for the Maldives in general.

The main struggles of the Maldivian health care system are both the remoteness of the island country itself and the wide distribution of the 1200+ islands that make it up. The remoteness of the country drives medical supplies and drug prices up by 15% to 75% than most other countries in the world [24]. Luckily for Maldivian citizens, drugs deemed essential by the government are free to access, however, that means the country’s Ministry of Health must front the cost of said drugs, putting the burden on the healthcare system. Another transport problem for some medical supplies and medications is temperature-sensitivity. This means providers / transports of these items must have temperature and humidity controlled environments all the way from the manufacturer to a Maldivian healthcare location [24]. Back in 2017, the Maldives made great leaps for its healthcare system by establishing health care centres and pharmacy on ever one of its inhabited islands, with a fleet of water ambulances [25]. In spite of these improvements, being a country made up of hundreds of small islands still leaves cracks within the healthcare system itself. Many of the smaller islands have limited access to skilled healthcare workers despite the centres being there for it is hard to attract such professionals to live and work in such small - and often underdeveloped - and isolated islands [24]. Because of the lack of healthcare professionals in these remote locations, often people have to travel to other islands or overseas for treatment: 66% of domestic travel in the Maldives in 2018 was due to medical purposes [24].

The first case of Covid-19 appeared in the Maldives in March (2020) and seemed relatively contained within a few of the resort islands, however, in mid-April just one case in the country’s capital caused and explosion of confirmed cases. The rapid rise of cases back in April caused six of the country’s inhabited islands to be locked down [26], now that cases are on the rise again the same risk of island lockdowns are at hand. It is suspected that many of the cases from the countries initial spike of Covid-19 cases came from Bangladeshi migrant workers living in the capital, Malé, who are subjected to cramped and poor quality living quarters causing the virus to rapidly spread leaving at least 416 confirmed cases from this population group[26]. Due to the high case rate in the Bangladeshi migrant community - and perhaps some nationalism and racial bias - 3 000 of these workers living in Malé we relocated to other, less inhabited islands with hopes for better social distancing to be possible there [26]. The Maldives also took to tackling rising Covid-19 in a new and innovative way which captured the attention of lots news sites across the world: luxury resort quarantine facilities! Due to it's many islands and sparkling blue waters the Maldives is host to many luxury resort across the country, which are often located on islands all to themselves. So when Covid-19 numbers began to spike in the country, many of these resorts lay empty, and health care facilities began to run short of beds the innovative idea to use some of these 5-star resorts as quarantine health care facilities. As of March 24th, 2020, 10 luxury Maldivian resorts have been converted to quarantine facilities - equaling some 1,158 rooms with 2,228 beds available for people with confirmed cases in the country helping to alleviate the country’s mere 470 hospital beds for more dire patients[27].

Green Recovery - Jet

The Maldives are widely known as an ideal vacation spot with a beautiful ecosystem that attracts people from all over the world. They are also “credited for becoming the first South Asian country to achieve universal electrification.”[3] Meaning that the entire nation has access to electricity, however the nation is heavily reliant on fossil fuels which puts their fragile ecosystem in an extremely vulnerable position.[3] The importation of fossil fuels are a main expenditure for the Maldivian economy and with lack of tourism income due to COVID-19 their economy is taking a large hit.[3] As a solution to these two problems, the Maldivian government has invested in renewable energy, the “Green Recovery” plan will not only help the environment but also strengthen the future economy.[3]

The Maldivian economy is struggling due to the pandemic, but they have decided to take this time, to rebuild and focus on the future of the nation, supporting their economy around renewable resources.[3] All Maldivian people have access to electricity, but it comes at an incredibly high price for everyone due to the extremely high power tariffs, among the highest in the region.[28] Importing the fuel into the Nation accounts for approximately one fifth of the country’s imports.[28] Currently, large external expenditures are a high risk for their economy because they have no income from tourism to give that needed boost.[3] As a buffer for the harsh effects the pandemic would take on the citizens, the “government has introduced a series of fiscal and monetary measures.”[28] The government is providing relief packages that provides “emergency financing for businesses, as well as income support for individuals and discounts on utility bills for poor and vulnerable households.”[28] As necessary as it is, providing discounts on electricity can only further damage the economy; the high price they pay for electricity and the loss of the main income, finding the money to pay for the fuel will be difficult. This issue is a main incentive for the government to take on the Green Recovery plan; so in the future the economy will benefit and be able to repair the damages the pandemic caused.[29] Renewable energy will be a long term investment rather than an easy solution. The initial investment will come at a high cost, however the nation will recieve assistance from organizations outside the country.[30] The Maldivian government was recently granted a $73 Million "concessional loan and grant" from the Asian Development Bank to create a proper waste treatment facility, using waste-to-energy technology.[30] As of right now, they do not have a proper waste disposal system as "over 830 tons per day of solid waste are generated in the area and dumped or burned at the 10-hectare dump site on Thilafushi Island."[30] Since the disposal system was established in 1992, there have been no pollution control measures which leads to the contamination of the environment around it and is detrimental to fisheries and tourism.[30]

A cycone recently bypassed Mumbai.[31] Neither Mumbai, nor the Maldives experience cyclones or natural disasters often, which served as a wakeup call to many civilians to demand climate action from the local government of Mumbai in hopes of decreasing the likelihood of future calamities.[31] The Maldives is in a similar situation to Mumbai, they are both on the Indian Ocean and so are also as susceptible to the rising risks coming from the "fastest warming ocean in the world."[31] As they share the ocean, the pollution that is coming from both destinations are having devastating effects on the enviornment, and if they continue it will increase the risk of future disasters. Mumbai has had demands for climate action however the government seems too focused on the economy and making money; “city officials are moved more by the mundane and material profits of real estates speculation than to ensure urban sustainability.”[31] The lack of appropriate response threatens property and the livelihoods of citizens and could have lasting consequences such as those in Nepal.[3]

Nepal in the past decade has experienced many disasters from a large earthquake in 2015, a civil war, landslides, and a pandemic.[32] If climate change increases so will natural disasters everywhere including Nepal and the Maldives. The way the Nepalis have dealt with previous disasters, provides us with some insight on how we should all be addressing the current one.[32] Any time a disaster occurs it will cause change. In Nepal when the earthquake hit in 2015, many people were displaced, lost their homes or died.[32] Rebuilding was difficult for some because not everyone had equal access to resources nor the money to rebuild.[32] The takeaway from the handling of the disaster was that instead of waiting to return to how it used to be, they “fashioned new lives through a combination of creativity, perseverance, carful use of available resources and hard-earned income, with some state and international intervention.”[32]

Climate change is a large issue in South Asia as many nations rely on fossil fuels, therefore the Maldivian example of investing in renewable resources could benefit other nations as well. For example in Lahore Pakistan they are also experiencing the effects of Fossil Fuels.[33] In the winter, “smog in Lahore is a calamity of visibility.”[33] Pollution is the primary cause of the low visibility, and citizens are asking that the government provides data on the air quality because they don’t know how bad it is.[33] Particularly with the addition of today's global pandemic, citizens need to be taken care of. The pollution in Lahore is a result of fossil fuels, it has serious effects on the environment and people's health which could increase vulnerability to viruses, something the Maldives is trying to prevent. The people of Lahore are not seeiking climate action but rather asking the government for transparency.[33] Between the nations along the Arabian Sea and Indian Ocean, the pollution emitting from fossil fuels are outrageous and are creating an "aerosolized fossil fuel emission..." that are blanketing the water.[31] All over the world climate change is heavily impacting ecosystems and cities. Reports are showing that with increasing climate change we are subjected to a higher risk of natural disasters.[31]

Disasters like the pandemic will affect everyone, but the pandemic will end and how we come out of it is what will determine how we carry on. "There is an end to the virus, but no end in sight to climate change."[3] In the Maldives as they roll out the Green Recovery plan they are focusing on reducing their carbon footprint. This will prove to be beneficial because not only will it cut energy costs by converting waste into energy, it will also benefit society through the creation of jobs, the saving of their beautiful environment, and by default increase sustainable tourism.[3]

Rising Extremism and Violence - Carson

Maldives is currently not only going through a public health crisis, but is also going through an economic and political crisis as well. The Country, which only officially achieved its independence from the United Kingdom in 1965[7], has had a complicated relationship with democracy and liberty. Some advocates of democracy say that this period of emergency for the country could be a dangerous opportunity for even greater power to be seized by corrupt officials, and personal freedoms to be stripped in the name of safety.

Post independence from the United Kingdom, Maldives elected to become a presidential republic. A number of years later in 1978, Maumoon Abdul Gayoom assumed the role of President, a role he would hold for 30 years. It wasn’t until after the Country was devastated by the 2004 Tsunami, in a similar way that neighboring Sri Lanka was hit[34][35], that the people of Maldives were able to push the necessary reforms to get their first democratically elected President. Mohamed Nasheed became President in 2008. He was also one of the founders of the Maldivian Democratic Party and came from a background of journalism and activism. His administration came to power in a period of instability for the Maldives, when the country was still reeling from the economic consequences and destruction of the Tsunami four years prior[8]. His time as President was cut short when he abruptly resigned in 2011. It came to light a short time later that he was forcibly removed from his position by mutiny of police and army officers. He was later arrested and sentenced to prison on charges of Terrorism. The UN labeled this trial as politically motivated and requested his immediate release. After spending a period of time as a political refugee in the United Kingdom, Nasheed returned to Maldives after Ibrahim Solih of the Maldivian Democratic Party took office as President, and the Supreme court appealed Nasheed’s sentence. In the midst of the controversies of Nasheed’s resignation, Nasheed appealed to the Commonwealth league of Nations to put pressure on the Maldives to hold a new election due to the circumstances of his expulsion. Maldives announced it’s resignation from the Commonwealth in 2016 in protest of the allegations. It has since rejoined the Commonwealth in February of 2020, showing sufficient progress in developing and following democratic processes. Although the Maldives has been recognized for it’s recent progress in this area, some people are concerned that civil unrest due to another economic downturn could be an opportunity for autocrats to seize power again.

Lockdown and social distancing associated with COVID-19 has been thought to lead to increased cases of domestic violence. The Maldives is no exception to this phenomenon, recording a significant increase in domestic violence in the months of April, May, and June[36]. These months were the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic world response, which is why more people were stuck at home. For people stuck in abusive relationships, this response makes it hard for victims to be out of the house and in a place of relative safety. The majority of these cases come from the city of Malé, the largest and highest population density city in the Maldives.

Maldives is a rapidly developing country, and thus has seen a significant amount of immigration and foreign workers enter its economy. It is noted that a portion of these workers are undocumented and are taken advantage of for cheap labour. The most recent incident concerning this is that the police in Maldives have recently arrested a group of 22 immigrant workers who were protesting a claim of not receiving pay for work for 6 months[37]. Some Government officials have taken a stance against workers such as these by speaking to claims that they are a violent and dangerous group in the Maldives society. International communities do not hold the Maldives immigration and foreign workers policies in high regard, with the United States labeling it on it’s “tier 2 watch list” for the level of human trafficking prevalent in the country. COVID-19 has further suppressed these groups because the virus is more likely to be present in populations that experience higher poverty and worse living conditions. The Maldives Government has been subject to criticism due to the harsh stance they have taken against these vulnerable groups in their society.

The Maldives has reportedly seen a rise in extremism in its population. In its recent history, politicians have been the target of several assassination attempts and physical threats. In 2018 a Presidential commission was put together to investigate the numerous cases of politically motivated violence. Reports of the rising potential of violence from the growing Islamic extremist population of the Country are causing concern for the Island Nation. A statistic reported by the Maldives police commissioner reports that almost 500 citizens attempted to travel to Syria or Iraq, and thus put the country in the world's highest per capita of foreign fighters to those countries. Progressives in the Country are concerned that the economic downturn due to COVID-19, combined with the rising extremism could lead to an environment that threatens the fledgling democracy of the Island Nation[38].

Migrant Workers Protest Human Rights Violations

The Maldives, due to its successful history with the World Bank and other organizations[4], has received millions in support funding for workers and health care establishments since Covid-19 has begun[1][39]. However, if this money is being used effectively, it has neglected at least one group of individuals. In fact, the Maldives has a rich history of migrant worker abuse and human rights abuses. In 2007, for example, it was reported that the Maldivian government threatened migrant workers with deportation to stop a protest in Malé. This was during a time when demand for migrants was high due to a construction boom[40]. “There are other instances where lack of legislation, and lack of enforcement, have hindered any efforts to tackle the problem. In 2009, a Bangladeshi man was chained inside a small room for weeks; the chains were removed only when the man was put to work. The employer was released after merely four months’ imprisonment due to lack of anti-trafficking legislation at the time.”[41] Mushfique’s article discusses many other rights abuses, reporting on “Transparency National’s statement: “Maldivian society in general views Bangladeshi expatriates as lower class non-citizens; harassment against them has been completely normalized. The authorities view them as the problem and not victims of discriminatory attacks and human trafficking offences.”[41]

With Covid-19, tensions have increased. Hosting an estimated “82,000 registered and 63,000 undocumented migrant workers in the Maldives – around one-third of the total population – the majority from Bangladesh,”[37] migrants workers make up a significant proportion of the population. They should have strong structures in place to support them during these times. But with the history of abuse, and the continued abuse, migrant workers are not able to find the resources they require to fulfill many of their basic human needs. Many have had wages withheld and been arrested for protesting[42], the president even campaigned on promising to restrict free speech and assembly[43]. These types of issues are highlighted by Covid-19, which itself poses a host of new risks and issues, especially for these migrant workers. Living in congested spaces, often forced to pay more for medical due to complications of migration (lack of documentation), and sometimes having documents seized by employers, migrant workers constantly need health care and have less access to it[44]. With a population as abused as this, it can be hard to track a pandemic. If illegal workers are scared to get deported, they are less likely to get tested or treated medically if they are ill, and are therefore more likely to spread the disease. With this added onto the already inhumane conditions of the large migrant worker population in the Maldives, we may be seeing a culminating point as we have seen in many other South Asian regions throughout different periods of time.

Despite sharing religion and language roots with a high percentage of its migrant populations (ex: language rooted in Sri Lankan dialect; many south asian countries have high muslim population including Bangladesh)[45], the government of the Maldives refuses to acknowledge their rights time and time again.

Yet in South Asia, migrant worker discrimination is the norm. For example in Sri Lanka’s free trades zones female migrant workers were regarded as a lower class and treated as such. Although they were very creative in their living situations and received more respect in general and had more space than migrant workers in the Maldives[46], it is just one example of the long standing segregation between migrant workers and native workers in regions of South Asia.

And so what can be done? More specifically, what can be done in response to Covid-19 and all of these breachings of human rights? How may Covid-19 be used as a catalyst for change in the region? As tourism has started back up in the Maldives, law firms are suing companies for unpaid wages. While nothing can be done about the trauma experienced throughout the beginning of the pandemic, there are individuals now that are stepping up to represent under-priviledged workers[37]. But it’s not enough. There needs to be structures in place that will not allow this type of treatment, even during a pandemic. Companies are manipulating illegal migrants and even legal migrant workers into working for free, and then working to silence their voices. And so “all of the technical skills and financial support in the world will have little impact, unless the social and political dimensions of such a large scale project are understood,”[47] and then addressed. If the same efforts were directed towards making migrant workers welcome and safe as they currently are to suppressing and silencing migrant workers, there would be a very different social world in The Maldives.

Implicit Bias in Tourism During COVID-19 - Parisa

The small island nation of the Maldives is ripe with culture and amazing stories. The beautiful seas and beaches play a part in the country’s culture and its very foundation. These stories, based on religion, develop the formation of the identity of the nation-state. Of particular, is the Raanamari, which involves kings, sea monsters, and a Muslim traveller who then starts spread the religious across the island provides the religious identity that is observed in the present[48]. The legends which surrounds the country, the splendid scenery of the coasts and islands, along with remoteness of its location creating an aura of seclusion and mystery is perhaps what garners the international attention on the country and in brings in visitors and tourists from all around the world. However, this global attention perhaps fuels a visible boundary and produces an invisible divide between the wealthy tourists and the locals which call Maldives their home, which is only exacerbated by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the Maldives tourism contributes greatly to the country’s overall Gross Domestic Product, accounting for an estimated 24.5%[49]. For this island nation, tourism is not just the renting of the exclusive resorts, but the revenue made on overall accommodation services as well as the beverage and food services and industry. In just 2018, the Maldivian government made an estimated revenue of 7,197.07 million in Rufiyaa. However, this upward economic growth has been severely hindered by the onslaught of the global pandemic. Countries were forced to temporarily close borders and the “tourism sector is the worst hit of all major economic sectors” and this is especially concerning as tourism is so influential in the Maldives, as it “accounts for majority of foreign exchange earning” (Maldives Ministry of Tourism, 2020)[50].

This sector in the Maldives was apparently so badly hit that that the impact was described as "rank[ing] up there with the 2004 tsunami and the global financial crisis" (Ossinger, 2020)[51]. To provide perspective and context, the 2004 tsunami that hit Sri Lanka left a mosaic of disasters across the coast which made it that much difficult to recover and repair the destruction that was left[52]. The fact that the financial damage done by only four months of closure was equivalent to the damage of a natural disaster is quite illustrative of how important tourism can be to the functioning of nation-states and the tens of thousands of people involved in the hospitality industry, both directly and indirectly.

The Maldives, currently, has re-opened borders to allow for tourism to re-continue and with that, new guidelines and restriction were produced restricting locals from being guests and accessing the tourist facilities for the sake of their safety as individuals from all over the world will be visiting the beaches and resorts in this nation[53]. Nevertheless, this can be further delved into as these restrictions provide a sense and perception that expensive resorts, beaches, and hotels are exclusive in nature and may only be open to those who are wealthy enough to afford it. Visiting the islands of Maldives is not cheap, almost all the island resorts are privately owned and along with the increase of price in flights and ensuring one is taking the precautionary measures to stay safe and healthy, those who can truly afford all that will most likely be visiting the Maldives this summer[51].

It is interesting to observe the different responses countries may have all around the world and it is often hard not to compare. In Canada, there is a new emphasis of local tourism, encouraging those who live in Canada to visit and see the natural wonders of their own country. This of course, is not the case in the Maldives which starts the discussion in general of tourism and how it may perpetuate binary narratives of, there are places for the rich to visit and tour and places for those not extravagantly wealthy to visit and see. Tourism it self may be divisive and create boundaries and restrictions based on socio-economic status, an implicit bias.

The Maldives, by providing an image of blue lagoons and sandy beaches for the select can be compared to the city of Gurgaon in India, which also facilitates a division among individuals based on socioeconomic status[54]. The Maldives, like Gurgaon, create this sense of being and inhabiting a place not like any other, a haven and paradise that only the wealthy seem to benefit from. This sense of perception, to those who can afford it, seems to allow the rich to become much more unaware and disconnected from the local individuals and their struggle and circumstance, as they are not directly a part of the remote sanctuary they inhabit. In the context of the Maldives, this concept is further exacerbated by the poor treatment of tourism workers, who have protested along the beaches about low wages, ill-treatment and poor working conditions, which has been an issue for a myriad of years.

The islands of the Maldives have a picturesque and scenery and unique tourist attractions that one can only dream of seeing. But, with the rising costs of air flights, hospitality services, and ensuring proper health care coverage that is exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic it makes it only harder for individuals who are not the select view to experience what Maldives offers so easily. Even in tourism there are implicit biases, that certain places are meant for a specific socio-economic group while others not and it provides insight onto how tourism itself may discriminate based on how much money an individual makes. Regardless, tourism is required for countries to thrive, succeed, and function and in the context of the Maldives that is especially true.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Bank, World (Aug 20, 2020). "Supporting Vulnerable Workers in Maldives Amid the Covid-19 Crisis". The World Bank.

- ↑ "Atolls of Maldives". Ministry of Fisheries and Agriculture.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 "Maldives Development Update: Unprecedented Crisis Presents 'Green Growth' Opportunities". The World Bank. June 18, 2020. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "The Maldives: A Development Success Story". World Bank. April 10, 2013. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- ↑ Bosley, Daniel (August 13, 2020). "The Maldives Faces a Twin Threat: COVID-19 and Rising Extremism". World Politics Review.

- ↑ Mohamed, Shahudha (August 7, 2020). "Maldives records highest global COVID-19 cases per capita: Our World in Data". The edition.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Ahmed, Rizwan (2001). "The State and National Foundation in the Maldives". Sage Journals. Cultural Dynamics: 293–315 – via Sage Journals.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Brechenmacher, Victor (April 22, 2015). "Autocracy and Back Again: The Ordeal of the Maldives". Brown Political Review. Retrieved Aug 19, 2020.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 "Equipping Health Care Workers in Maldives to fight COVID-19". World Bank. June 11, 2020. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ↑ "IMF Executive Board Approves a US$28.9 Million Disbursement to the Republic of Maldives to Address the COVID-19 Pandemic". April 22, 2020. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ↑ Sharma, Aditya (April 15, 2020). "Coronavirus hits Maldives' lucrative tourism industry". DW.com. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Sheniderman, Sara (April 23, 2020). "Learning from disasters: Nepal copes with coronavirus pandemic 5 years after earthquake". The Conversation. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ↑ "World Bank Approves $12.8 Million to Support Maldives' Workers Impacted by COVID-19". The World Bank. June 9, 2020. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Shneiderman, Sara (October 14, 2015). "Dots on the Map: Anthropological Locations and Responses to Nepal's Earthquakes". Society for Cultural Anthropology. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Warner, Cameron David (October 14, 2015). "Introduction: Aftershocked". Society for Cultural Anthropology. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ↑ Miglani, Sanjeev (November 23, 2018). "After building spree, just how much does the Maldives owe China?". Reuters. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "The World Bank In Maldives". World Bank. April 10, 2020. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- ↑ Bremmer, Ian (June 12, 2020). "The Best Global Responses to COVID-19 Pandemic". Time. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ↑ "Maldives". World Health Organization (WHO). April 14, 2012.

- ↑ "COVID-19 LOCAL UPDATES". Ministry of Health, Republic of the Maldives. August 15, 2020.

- ↑ Mohamed, Shahudha (August 7, 2020). "Maldives records highest global COVID-19 cases per capita: Our World in Data". The Edition.

- ↑ "Equipping Health Care Workers in Maldives to Fight COVID-19". The World Bank. June 11, 2020.

- ↑ "World Bank Fast-Tracks $7.3 Million COVID-19 (Coronavirus) Support to Maldives". The World Bank. April 2, 2020.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 Badeeu, Fathimath Nashwa; Nafiz, Aminath Reesha; Muneeza, Aishath (April 7, 2019). "Developing Regional Healthcare Facilities in Maldives through Mudharabah Perpetual Sukuk". International Journal of Management and Applied Research. 6.

- ↑ Sharma, Shamila (September 8, 2017). "Ministry of Health Maldives gets WHO Excellence in Public Health Award". World Health Organization.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Sharuhan, Mohamed; Francis, Krishan (May 10, 2020). "Maldives Sees Rapid Spike in COVID-19 Patients". The Diplomat.

- ↑ "As coronavirus hammers tourism, Maldives converts vacant resorts to quarantine centres". Maldives Insider. March 24, 2020.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 "Investments in Renewable Energy can support Post COVID-19 Economic Recovery in the Maldives". Modern Diplomacy. June 16, 2020. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ↑ "Investments in Renewable Energy can support Post COVID-19 (Coronavirus) Economic Recovery in the Maldives". The World Bank. June 15, 2020. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 "ADB Approves $73 Million Package to Develop Waste-to-Energy Facility in Maldives". Modern Diplomacy. August 13, 2020. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 31.5 Anand, Nikhil (June 4, 2020). "Before the next disaster: What Mumbai needs to learn from Cyclone Nisarga". The Indian Express. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 Schneiderman, Sara; Baniya, Jeevan; Le Billon, Philippe (April 23, 2020). "Learning from disasters: Nepal copes with coronavirus pandemic 5 years after earthquake". The Conversation. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 Hong, Caylee (March 26, 2020). "Visualize-ing Air: Data, Icons, and Translations of Smog in Lahore". Society for Cultural Anthropology. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- ↑ Stirrat, Jock (October 2006). "Competitive Humanitarianism: Relief and the Tsunami in Sri Lanka". Anthropology Today. Vol. 22, No. 5: 1–6 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Gamburd, Michele (2013). The Golden Wave: Culture and Politics after Sri Lanka’s Tsunami Disaster. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- ↑ Munavvar, Rae (Aug 17, 2020). "Maldives records 100 domestic violence reports in second quarter". The Edition. Retrieved Aug 19, 2020.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 "Maldives: Migrants Arrested for Protesting Abuses". Human Rights Watch (HRW). July 24, 2020. Retrieved Aug 19, 2020.

- ↑ Bosley, Daniel (Aug 13, 2020). "The Maldives Democracy Faces a Twin Threat: COVID-19 and Rising Extremism". World Politics Review.

- ↑ Madardo, Abad (25 June 2020). "ADB Approves $50 Million Support for Maldives' COVID-19 Response". Asian Development Bank.

- ↑ Zafar, Nihan (September 3, 2007). "Maldives: Inhuman Treatment of Migrant Workers". GlobalVoices. Retrieved Aug 20, 2020.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Mushfique, Mohamed (1 April 2015). "Migrant workers' voice: illegal and silenced in the Maldives". AP Migration.

- ↑ Stuber, Sophie (28 July 2020). "In the Maldives, coronavirus worsens plight of migrant workers". The Observers.

- ↑ "Maldives: Free Speech, Assembly Under Threat". Human Rights Watch (HRW). 14 July 2020.

- ↑ Gossman, Patricia (27 March 2020). "Migrant Workers in Maldives at Added Risk from COVID-19". Human Rights Watch (HRW).

- ↑ Visweswaran, Kamala (2011). Perspectives on Modern South Asia. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 1–9, 48–51, 114–118.

- ↑ Hewamanne, Sandya (2008). "City of Whores". Social Text. 26: 35–39 – via e-Duke Journals.

- ↑ Shneiderman, Sara (2018) Expertise, Labour and Mobility in Nepal's Post-Disaster Reconstruction. Peter Wall Institute for Advanced Studies

- ↑ Ahmad, Rizwan (2001). "The State and National Foundations in the Maldives". Sage Journals. 13: 293–315.

- ↑ Maldives Ministry of Tourism. "Tourism Yearbook 2019".

- ↑ Maldives Ministry of Tourism (July 15, 2020). "Maldives Welcomes Back First Tourists".

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Ossinger, Joanna (July 9, 2020). "The Maldives Is Reopening and, Yes, Even Americans Are Allowed". Bloomberg.

- ↑ Stirrat, Jock. "Competitive Humanitarianism: Relief and the Tsunami in Sri Lanka". Anthropology Today. 22: 11–16 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Maldive Ministry of Tourism. "Revised Guidelines - Restricting locals from using tourist facilities".

- ↑ VPRO Documentary. "Gurgaon, the new urban India - VPRO documentary - 2009". Youtube.

| This resource was created by the UBC Wiki Community.It is shared under a CC-BY 4.0 International License. |