Course:LIBR548F/Lithography

Lithography is a printing process discovered by Alois Senefelder in Munich around 1798/1799.[1] Although Senefelder simply intended to invent a more economical manner in which to print his own writing,[2] the result was the development of what was essentially the first new printing process since the fifteenth century (which was that of printing from type and wooden blocks or copper plates),[3] and of the process which was to be used by the majority of printers from the second half of the twentieth century to the present day.

Basic Principle and Process

The essence of the process of lithography, or chemical printing from stone, can be summed up in the expression “like water off a duck’s back”[4]—in other words, lithography relies on the natural tendency of grease and water to repel one another.

Basically, a limestone slab (this stone having given lithography its name) acts as a surface on which marks can be made with a greasy crayon or ink. After the marks have been made, the stone’s surface is covered with a gum Arabic solution containing a small amount of nitric acid, allowed to dry, and washed off. The stone is then dampened with water, and the bare, porous stone absorbs water, while the greasy marks reject it. Similarly, when the stone is then rolled with greasy printing ink, the greasy marks attract the ink while the damp stone rejects it. Thus, this planographic process, rather than being dependent on differences in relief, relies on the chemical differences between the printing and non-printing areas on the lithographic stone.

From the beginning, the inconvenience of heavy and cumbersome limestone slabs encouraged lithographers to seek alternatives, and stone was gradually replaced by thinner zinc or aluminium plates which were mechanically ground to create a porous surface.[5] After the invention of the rotary offset press, the use of metal or composition plates became customary, and lithographic stone is no longer used in the commercial printing trade.[6]

Historical Development

Lithography was slow to emerge as a force in the printing trade or as a challenger to the dominance of letterpress printing—beyond Munich, the lithographic trade did not exist in any real sense until the 1820s,[7] when it began to spread to other European centres and elsewhere in the world.[8]

Some of this slowness can be explained by the distinct disadvantages the lithographic process had in comparison to letterpress printing. At a time when use of the hand-press was standard, lithography necessitated an additional step which resulted in a slower process: the dampening of the printing surface. Furthermore, lithography lacked an authoritative means of text origination which could effectively compete with the regularity of form and spacing offered by typeset.[9] However, lithography also offered distinct advantages which encouraged its use in certain fields.

Advantages of the new process

A significant advantage offered by the lithographic process was its flexibility or freedom from constraints. This was especially evident when combining pictures with text, but also when creating diagrams, reproducing handwriting, and when dealing with characters not commonly available in type form (e.g. non-Latin characters).[10] In addition, lithography eliminated the intervention of an engraver and empowered writers, artists, and non-professionals to create their own marks freely, quickly, and spontaneously.[11] Furthermore, in comparison to letterpress or intaglio printing, lithographic materials and equipment were also relatively inexpensive,[12] encouraging do-it-yourself and in-house production where one could control the entire process.[13]

A major reason for the versatility and freedom made possible by lithography was the transfer process, in which creators could first create marks on special “transfer paper” and then transfer their work to lithographic stone. Thus, creators were not forced to produce a reversed image, could consequently see their work in the same manner in which it would appear on the final print, and could more easily make corrections if necessary.[14] Furthermore, the transfer process enabled any kind of print—including lithographs, engravings, and typeset—to be transferred to lithographic stone.[15]

Some early uses

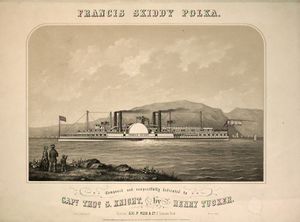

One of the first conventional publishing sectors to realize the advantages of lithography was music publishers—indeed, lithography’s first commercial focus was music publication.[16] Lithographed music was free from the control and rigidity of the punch and fonts of music engravers, and exhibited great variety in notational appearance—something which was especially apparent when musicians wrote out their own work using transfer paper.[17] Music covers or title pages also made good use of lithography’s capacity to merge images with text, with finely drawn vignettes being combined with skilful lettering.[18]

From the 1820s, mainstream book publishers used lithography to produce monochrome book illustrations, gift books, decorated covers and, by the close of the nineteenth century, widely-circulated chromolithographed (lithographs printed in colour) books.[19] Chromolithography exhibited the greatest versatility among the colour-printing processes of the time, thereby posing a significant challenge to the letterpress trade.[20] The illustrative powers of lithography were used in the books of botanists, geographers, and antiquaries[21]—European Egyptologists, in particular, made considerable use of lithography’s facility to reproduce non-Latin characters.[22]

Significantly, the ability to easily produce non-Latin characters encouraged the acceptance of lithographic book production as orthodox in many non-European parts of the world, particularly in the Middle East and South East Asia—indeed, letterpress printers and type for local scripts did not exist everywhere, and lithography had the additional advantage of “respecting calligraphic traditions and religious conventions” in the Muslim world.[23]

From letterpress to lithography

In 1904, a lithographer in America named Ira Rubel developed the idea of a rolling press with both a metal printing and a rubber transfer cylinder, thereby inventing offset lithography.[24] The image to be printed is first transferred to the rubber cylinder, and then on to the paper against which the cylinder passes. The speed and economy of this rotary press made lithography competitive with letterpress at the machining stage.[25]

As the first half of the twentieth century progressed, the printing industry was mechanized and photography was increasingly used at the origination stage, resulting in the restricted use of relief printing due to its inability to easily couple with photographic methods.[26] Following the Second World War and the advent of photocomposition, photolithography and lithographic printing eventually replaced letterpress printing, and printing became “virtually synonymous with lithography.”[27]

Annotated Resources

Porzio, Domenico, ed. Lithography: 200 Years of Art, History & Technology. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1983.

- This resource is comprised of a number of articles covering lithography’s invention and technical evolution, history, relationship with the artist, and capacity as both an artistic and social medium. It provides a primarily art historical focus, and well-conveys the freedom which lithography gave to the artist-originator of a print.

Twyman, Michael. Breaking the Mould: the First Hundred Years of Lithography. London: British Library, 2001.

- Michael Twyman, former Professor of Typography and Graphic Communication at the University of Reading, has produced a well-researched, historically-minded resource which gives an excellent treatment of the development of the lithographic process, various applications and users, with a particular emphasis on the growth of the lithographic printing trade and printers—all within the scope of lithography’s approximately first hundred years of existence. This is an especially valuable resource in that it moves beyond a discussion of lithography simply in terms of art history or fine-arts applications.

Weber, Wilhelm. A History of Lithography. London: Thames & Hudson, 1966.

- Wilhelm Weber provides a roughly chronological overview of historical developments in the realm of lithography as an artistic medium, often devoting chapters to historically significant artists. This resource gives clear explanations of basic lithographic processes.

References

- ↑ Michael Twyman, Breaking the Mould: the First Hundred Years of Lithography (London: British Library, 2001) 4; Wilhelm Weber, A History of Lithography (London: Thames & Hudson, 1966) 17.

- ↑ Michael Twyman, The British Library Guide to Printing: History and Techniques (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1998) 47.

- ↑ Twyman, Breaking the Mould, 3.

- ↑ Twyman, Breaking the Mould, 2.

- ↑ Domenico Porzio, ed., Lithography: 200 Years of Art, History & Technology (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1983) 36.

- ↑ Twyman, Breaking the Mould, 2.

- ↑ Twyman, Breaking the Mould, 24.

- ↑ Twyman, British Library Guide, l49.

- ↑ Twyman, Breaking the Mould, 46.

- ↑ Twyman, Breaking the Mould, 132.

- ↑ Porzio 223.

- ↑ Twyman, Breaking the Mould, 45, 166.

- ↑ Twyman, Breaking the Mould, 132-133.

- ↑ Porzio 38; Weber 17.

- ↑ Twyman, Breaking the Mould, 45.

- ↑ Twyman, Breaking the Mould, 24.

- ↑ Twyman, Breaking the Mould, 5.

- ↑ Twyman, Breaking the Mould, 136.

- ↑ Twyman, Breaking the Mould, 127.

- ↑ Twyman, Breaking the Mould, 102.

- ↑ Weber 76.

- ↑ Twyman, Breaking the Mould, 155.

- ↑ Twyman, Breaking the Mould, 158.

- ↑ Porzio 35.

- ↑ Twyman, British Library Guide, l78.

- ↑ Twyman, British Library Guide, l76.

- ↑ Twyman, Breaking the Mould, 3.

Credits

All images are in the public domain, and are from Wikimedia Commons: http://commons.wikimedia.org/