Course:GEOG350/Archive/2012WT1/Lower Lonsdale

Austerity and Gentrification: Lot 5 and the Future of Lower Lonsdale's Post-Industrial Waterfront

Introduction

Lower Lonsdale runs along Lonsdale Avenue, stretching northwest from Lonsdale Quay to Keith Road. Lower Lonsdale is located along the Vancouver Harbour, with the neighbourhood, Moodyville, adjacent to the east, Central Lonsdale adjacent to the north and Marine Hamilton adjacent to its west. The historic Wallace Shipyards was the industrial heart of Lower Lonsdale from the first decade of the 20th Century until a slide into receivership in the 1980s. The waterfront site lay derelict and closed to the public for decades. After exhaustive study and consultation, a redevelopment project including a mixture of preserved heritage structures and new construction has progressively transformed the site for the past decade. The keystone of the new development was to be the National Maritime Centre of the Pacific and Arctic, a museum to highlight the industrial heritage of the site. Provincial funding for the Centre was pulled in January 2010 and the future of the space has been in a state of uncertainty since.

This old shipyard site, which is now referred to as Lot 5, provides Lower Lonsdale with an exciting opportunity to redevelop its waterfront. According to Jacobs (1961) community vitality is maintained through "diversity, marginal activities, its tensions and its creativity" (cited in Stevens and Dovey 2004:364). In order to avoid the trap of creating a placeless, formularized waterfront, Lower Lonsdale will need to ensure that redevelopment holds the latter definition in mind. Not only does Lot 5 and the Lower Lonsdale waterfront have historical value, it also holds the potential for the community to attract more residents, tourists, investors and the creative class, all of which will help ensure a successful future.

Since 2002, and after funding was pulled for the National Maritime Centre, The City of North Vancouver has planned the redevelopment of the site be a mixed residential, commercial and cultural precinct in their Official Community Plan. However, there are many issues and conflicts that have prevented redevelopment. Clashing interests, displacement of local residents, the question of how to create a cultural core and how to appropriately preserve the site's heritage are all issues that have come to the surface in the planning process. Additionally, since the land is traditionally Squamish First Nations land, integrating their goals for the area is another challenge. Furthermore, with the withdrawal of provincial and federal funding for the Maritime Centre, the municipal government must now solely rely on their revenues or find other means for development.

This project will analyze the issue of how to develop this site (Lot 5) in the absence provincial and federal support. Solutions proposed will advance the aims of creating a public place of value to the local community, integrating the site with the rest of the neighbourhood, providing economic benefit to the area and preserving the history embedded within the space.

History

History of Lower Lonsdale

Over the past century and a half, Lower Lonsdale and its surrounding neighbourhoods have undergone drastic transformation. The temperate rainforest that once covered Lower Lonsdale has been cut and is now the home to a growing and vibrant urban community. Before the emergence of today’s neighbourhood, the First People to call this parcel of land home was the Squamish Nation (NVMA 2010). The Squamish peoples built permanent villages and fishing camps along the community’s shoreline and river-inlets, sustaining themselves by fishing, hunting and food-gathering (NVMA 2010). Just over 200 years ago, the Squamish peoples had their first encounter with Europeans (NVMA 2010). The Spanish were the first to arrive, however, shortly after, in 1792, Captain George Vancouver of England arrived, exploring the shores of North Vancouver (NVMA 2010).

Streetcars and Ferries

North Vancouver officially became its own municipality in the August of 1891 (NVMA 2010). In 1906, electricity and telephone service were introduced at the Lonsdale town site and in 1907 the City of North Vancouver became officially incorporated (NVMA 2010). Throughout the early Twentieth Century, Lower Lonsdale and its surrounding neighbourhoods began to develop a unique urban character; hotels, banks, a newspaper, and even a streetcar service were established (NVMA 2010). In fact, Lower Lonsdale was a central area serviced by the streetcar system, running along Lonsdale Avenue from 1912 until 1947 (NVMA 2010).

The years following the City’s incorporation were marked by a real estate boom (NVMA 2010). The construction of housing closely trailed the streetcar system and many of the oldest homes still in North Vancouver and Lower Lonsdale are situated near streetcar routes (NVMA 2010).

Due to North Vancouver’s unique geographic position of being enclosed on three sides by water and blocked by mountains on the fourth side, access to the rest of Vancouver was initially restricted (NVMA 2010). In 1866, the first ferry service was established, allowing access across the inlet (NVMA 2010). Between 1900 and 1958, freight and passenger ferry service from Lower Lonsdale avenue allowed direct connection to the rest of the Lower Mainland (NVMA 2010). The construction of the Second Narrows Bridge, which later became replaced by the Ironworkers Memorial Bridge, and the Lions Gate Bridge increased the North Shore’s accessibility but also caused ferry revenues to plummet and its eventual demise (NVMA 2010). The discontinuance of Lower Lonsdale’s ferry service meant a loss to the neighbourhood’s unique transportation system; however, the bridges offered new hope for economic development at a moment when the area was in financial crisis (NVMA 2010).

History of the Wallace Shipyards

The Wallace Shipyard, named after its original owner and operator, Alfred Wallace, opened in 1906 and grew into one of the most prominent industrial sites in Canada (CNV 2005). Over the course of its operation, the Shipyard changed names several times from Wallace Shipyards to Burrard Dry Dock, Burrard-Yarrows and eventually Versatile Pacific (CNV 2005).The Wallace Shipyard launched over 450 ships (CNV 2011) and was a site of impressive accomplishments, including the building of Mabel Brown in 1917, the SPR ferry Princess Louise in 1921, and the R.C.M.P. schooner St. Roch in 1928 (CNV 2005). In fact, the latter is now a National Heritage Artifact at the Vancouver Maritime Museum (CNV 2005).

The Shipyard’s productivity reached its height during World War II, employing the largest number of shipyard labourers in British Columbia (CNV 2005). During the war the Shipyard was a main producer of war ships in Canada, building approximately a third (109 out of 312) of the “Victory Ships” (CNV 2005). Shipbuilding during this time enabled North Shore’s economic recovery, allowing the District to emerge from receivership (NVMA 2010). As Lower Lonsdale became a hub for shipbuilding, entire subdivisions were created in order to house the large workforce (CNV 2005). In 1940, the city’s population had less than 9,000 residents; however, between 1942 and 1945, almost 20,000 people moved to North Vancouver to work at the shipyards, much of whom concentrated around Lower Lonsdale (NVMA 2010). The Wallace Shipyard’s contribution to the war effort was so great, in fact, that when the war terminated, Clarence Wallace was honoured as “Commander of the British Empire” (CNV 2005).

The glory of the Wallace Shipyard soon waned as shipbuilding activities slowed and the ship repair industry began to develop (CNV 2005). During this postwar period, Ice Breakers and super ferries were constructed (CNV 2005). In 1971 the Wallace family sold the Shipyard (CNV 2005). Due to an abundance of shipyard facilities in B.C., the Wallace Shipyard (then known as the Versatile Pacific Shipyard) closed in the early 1990s (CNV 2005). Despite an overall closure, a portion of the dock, to this day, still remains in operation (CNV 2005).

The Neighbourhood Today

Demographics

In 2006 Lower Lonsdale had a population of 12,740, making it the largest of the North Shore neighbourhoods (CNV 2009:2). It was also the fastest growing neighbourhood, with a 4.4% growth rate (615 residents) between 2001 and 2006 (CNV 2009:2). Lower Lonsdale had a low concentration of children and youth with only 13 percent of its residents under the age of nineteen (CNV 2009:4). In contrast, seniors, aged 55 and older, constituted 24 percent of the neighbourhood’s population (CNV 2009:6). The average family income in Lower Lonsdale in 2006 was $66,000, increasing, like all neighbourhoods in the municipality, during the past Census period (CNV 2009:7).Between 2001 and 2006 Lower Lonsdale added 375 new private dwellings (CNV 2009:8).

Densification in Lower and Central Lonsdale accounted for 88 percent of the citywide increase in household numbers and was due largely in part to redevelopment projects in the area (CNV 2009:8). The 2006 Census reported more apartment dwellings in Lower Lonsdale than there were single-detached and other ground oriented dwellings in the City’s other neighbourhoods combined (CNV 2009:9). Residences in apartments with five or more storeys were only reported along the Lonsdale corridor (CNV 2009:9). The number of owned dwellings in Lower Lonsdale remains low (45 percent), although the neighbourhood has experienced a marked growth (18 percent) in the number of ownership rates between 2001 and 2006 (CNV 2009:10). Lower Lonsdale is also characterized by its high mobility rates, with 63 percent of residents having moved during the five years preceding the 2006 Census (CNV 2009:11).

Transportation

In 1977, the publically funded Translink SeaBus began ferrying passengers between the Downtown Vancouver Waterfront station and the North Vancouver Lonsdale Quay station (Translink). With a capacity of 400 passengers, and a current crossing time of only twelve minutes, it has figured prominently in Lower Lonsdale’s land use transformation and corresponding gentrification (Translink). As a result of creating an efficient means to commute across this channel of water, the significance of North Vancouver as a suburb of the City of Vancouver was increased. Directly outside the Lonsdale terminal is a central bus station that services buses all over the City and District of North Vancouver, as well as linking North Vancouver with West Vancouver.

Land Use Profile

Lot 5

In 2006, the previous shipyard was granted National Historic Status and an industrial heritage precinct with buildings and artefacts that reflect the character of the historic shipyard were built (CNV 2011). The western section of the site is 110,000 sq/ft but has remained unoccupied since the closure of the Shipyard and is now used mainly for filming movies (CNV 2005). It is this vacant portion that is now under review and owned by the city with hopes to be redeveloped but no agreements have been made (CNV 2005).

The Wallace Shipyards Site Today

According to Marshall (2001), the city’s form is becoming less the product of design and more a manifestation of economic and social forces. Presently, our information based, service-oriented economy no longer requires the industrial activity of the past (Marshall 2001). Lower Lonsdale’s industrial decline, specifically, in relation to the Wallace Shipyard, as with the much of the rest of the Western Hemisphere, matched the ideological, economic and political shift from Keynesianism to neo-liberalism (Bunting et al. 2010). This shift has entailed a decline and transformation of Canada's manufacturing sector, a growth in knowledge-based economic activities and an increase in creative and cultural industries (Bunting et al. 2010). In contrast to the material production focussed industrial city, the post-industrial city address "immaterial production... that of common non-material goods:services, information, symbols, values, aesthetics, in addition to knowledge and technology" (Vaz and Jacques 2007, 242). In this new "cultural economy", the urban waterfront, in Lower Lonsdale and elsewhere, is what Marshall (2001) refers to as a “new frontier” for development processes. The contemporary waterfront has become prized for its high visibility, allowing for projects that mark its edges to be amplified intersections of various urban forces (Marshall 2001). As a result of shifts in technology and economic and political systems, the waterfront has become a space that allows the opportunity to display contemporary ideas of the city, society and culture (Marshall 2001). Discourses surrounding the redevelopment of Lower Lonsdale’s Wallace Shipyard Site also seem to indicate the project as an attempt to create an emblem of contemporary ideas.

Pinnacle Redevelopment: "The Pier"

Preliminary plans for redevelopment began in 1995, when the City, along with the Dock’s owners, undertook a Land Use Study. The result was the Versatile Shipyard Land Use Study, which was officially approved in 2001 (CNV 2011). The project entailed keeping the Panamax Drydock (now Vancouver Drydock) as a working shipyard on the eastern portion of the site (CNV 2011). The western portion, however, was designated as a site for redevelopment to urban uses, aimed at reinforcing the surrounding Lonsdale Regional Town Centre (CNV 2011). In 2001, Pinnacle International purchased the development rights to the site and relabeled the development “The Pier” (CNV 2011).

According to the City of Vancouver Website (2011), the Pier Development (now known as Lot 5) currently includes: a total of 1.25 million sq ft of commercial, public amenity and residential development; increased public waterfront access and a performance stage; a 700 ft public dock for visiting ships (Burrard Drydock Pier); a floating dock for smaller boats; an industrial display with buildings and artifacts that showcase the character of the historic shipyard; 108 room Pinnacle Hotel; commercial uses with various shops, restaurants and services; 1,000 apartment and live-work units; 50 underground parking stalls; soil contaminant remediation; and infrastructure improvements.

The Pier Development Site Plan

Current Issues Facing Lower Lonsdale

Clashing Interests and Displacement

The current entrepreneurial phase of urban development is centered on financial gain, spectacle and consumption (Bunting et al. 2010). In addition, cities have become interested in designing the environment so that it contributes to a positive image of place (Bunting et al. 2010). This process of place-making is becoming essential in an ever-increasing competitive global market. Municipalities are invested in forming a unique image attractive to tourists, investors, and the creative class (Bradley et al. 2002). These efforts are geared towards replacing negative perceptions of post-World War II environments with more positive visions of growth and success (Bradley et al. 2002). Similarly, redevelopment plans in Lower Lonsdale can be conceptualized as a process aimed at rejuvenating its urban image – one that has been plagued by industrial decay.

In this process of ‘place-remaking’, culture is a paramount feature of economic development (Bunting et al. 2010). The emphasis on culture is clear in Lower Lonsdale's waterfront redevelopment project, for example, its exhibition of the historic shipyard, the inclusion of a performance stage, its various spaces for retail consumption, as well as a number of restaurants. All of these aspects emphasize the area’s push to be re-identified as a cultural node. In this place-making process one of the major questions is who will be excluded and who will be included, or as Bunting et al. (2010) put it, “is this so-called ‘circus’ serving those in need of ‘bread’ and other necessities of life”? Considering the increasing socio-economic polarization occurring across Canadian cities, counting on a “trickle-down” effect here will also likely prove unfruitful. Pacione (1997) echoes this view surrounding the "trickle-down" effect, arguing that rather than social needs being met as a result of an increased municipality revenue base, funds will be funnelled toward increased development. Although the Lower Lonsdale redevelopment project will generate profit for Pinnacle (the main developer) and increase the tax base of the city, the interests of others will potentially be sidelined in the process. As Pacione (1997, 31) notes, "social criteria fit awkwardly into the conventional balance sheet of economic progress". In reality, residents whose needs are least in line with private, market-based interests will likely be further marginalized (Bunting et al. 2010). This marginalization could potentially displace many residents whose needs are no longer met due to the area's redevelopment.

Lack of Cultural Core

With the increased residential development seen in Lower Lonsdale and nearby neighbourhoods, the importance of a ‘cultural center’ becomes more important. Lonsdale Quay stands as the primary social meeting place in the area, made popular by a diverse marketplace and its close proximity to the SeaBus terminal. Else where in Vancouver the waterfront is very active and a hub for social and recreational activities. However, the waterfront along Lower Lonsdale has minimal activity because there is little there to draw people to the shore. Additionally, there is nothing in Lower Lonsdale to attract tourists, which are an important source of income for cities. Lot 5 sits directly beside Lonsdale Quay on the water, the land once territorialized by industry has become available to the public. Lot 5’s development is an opportunity to complement Lonsdale Quay as a ‘cultural center’ by creating a space for people of all socio-economic backgrounds to meet.

Funding Limitations

In consideration for approving Pinnacle’s development of “The Pier”, the City of North Vancouver received “Lot 5” (CNV 2011). The original plan of building a National Maritime Centre, showcasing the historic significance of the site, became unattainable due to pulled Provincial funding. Consequently, the financial burden of developing the site has been placed on the City, which has limited the scope of possibilities. In order to overcome this obstacle the City needs to develop the site within the financial bounds of their municipal revenues, or must find a strategic partner who can help shoulder some of the costs. An example is partnering with the Vancouver Aquarium to develop a North Shore exhibit, an idea which has recently been proposed.

Integration of Squamish Nations

The Mission Indian Reserve is situated at the southwestern-most boundary of the City of North Vancouver. The Reserve is , comprising a significant area of Lower Lonsdale (Metro Vancouver, 2012). It is home to one of the sixteen tribes comprising the Squamish Nation, which is the largest First Nations group currently residing in Metro Vancouver (Metro Vancouver, 2012). Currently, the Reserve is very isolated from the economic transformation that is underway in Lower Lonsdale. In order for Lower Lonsdale to meet its full potential, this cultural border needs to be addressed in a way that brings these First Nations into decision making to help them prosper. Therefore, with a goal of creating a public place of value for the community, it is important that the First Nations of Lower Lonsdale are fully integrated into the planning of Lot 5’s development.

Preserving Heritage

Evidently, the area holds a lot of treasured history. However, this history causes conflict in the redevelopment plans around preserving heritage and post-industrial waterfront development . The lot is currently empty except for steel from the frame of the old ship. Additionally, a old ship stern from the Flamborough, a victory ship built on the site still remains in tact but covered being preserved for restoration.

Significance of the Future of Lot 5

The redevelopment of Lower Lonsdale and the Versatile Pacific Shipyards will add 10% to 15% to the City's population (Social Plan 1997).

Prior to the funding cuts to a proposed National Maritime Museum of the Pacific and Arctic, Lot 5 was planned to be the lynchpin of the new development—a public place that preserved and documented the history of the site while furthering municipal aims to develop a tourist-centric economy for the neighbourhood. The future of the Wallace Shipyards site has been a core focus of the City of North Vancouver since the 1990s, when the City approved a development plan, the Versatile Shipyards Land Use Study, along with the Lower Lonsdale Planning Study Use Area (CNV 2011).

Solutions

"We need new strategies and the political will to alter the trajectory that is creating one city for the very liquid rich and another for everyone else" (Hern 2010).

Community Engagement and Activism

"People have to make cities by accretion: bit-by-bit, rejecting master plans and letting the place unfold. Whether it's our safety, governance or urban planning, it's everyday people who can make the best decisions. But for this to be possible, cities need engaged citizens: people who are willing and able to participate in common life- and governance structures that actively encourage them" (Hern 2010).

This quote by Matt Hern from "Common Ground in a Liquid City," expresses the importance of community involvement in planning cities. Cities and more specifically developments need to cater to its citizens so they represent their wants, needs and a place where they want to be. Matt Hern also states that the real issue is how to create an organic, unfolding city, one that is not run by bureaucratic planning or rampaging developers but is driven by a million decisions made by people on the ground (Hern 2010). A successful example of community engagement in planning is the Surrey East Clayton neighbourhood. The result is a neighbourhood that specifically caters to its citizens needs with affordable housing, live-work zoning and integration of commercial and business zones (Connelly and Roseland). This mixed land use model may be one North Vancouver could adopt.

During the neighbourhood planning process it is important to talk to those who are not normally heard. The North Vancouver urban forum has adopted this and understands the necessity of community engagement in the redevelopment of the pier. The North Van Urban Forum's mission is to channel community energies towards a thoughtful, richly collaborative and thoroughly community rooted development of the urban space to ensure transparency in the development processes (North Van Urban Forum 2012). The forum is currently hosting a design jam contest for the development of Lot 5. Anyone is able to submit their ideas visually or as an essay. The winners and shortlisted entries will be displayed in a local cafe, posted on the forum website, awarded a prize and a summary report will be submitted to representatives of the City of North Vancouver. Although the North Van Urban forum is not affiliated with the government it still fosters community involvement and shows the city that citizens can actively be engaged in developing lot 5.

A Public Space

In the development process it is important that public space be emphasized in order to cultivate a sense of community and interaction. Matt Hern states “a city should be the best of humanity: an ethical union of citizens drawn together by mutual aid and shared resources. And that sharing means public space or better yet, common space” (Hern 2010). At the urban design talk one participant noted, “people want something there, they want to use it.” Also this portion of the waterfront should be a platform of enablement where people can arrive and make a place out of the space. This raises the question, what can be there that will attract people? One possibility is keeping artifacts from the shipyards on display for the public to view without cost. This would enliven the site and be valued by those who want to remember but also teach future generations of the history. A world of possibility is driven by public space that turns into common places and neighborhoods. That is what makes a great city, not the shopping opportunities (Hern 2010). Globalization and corporate expansion have rendered the cores of most cities; Lower Lonsdale, however, for the most part, has avoided this and it will be important for the community to continue to steer clear of creating a rapidly developed, corporate, manufactured space (Bunting 2010). A public space needs to be focused around the past culture with seating, some businesses, history and creative spaces to create a unique environment to bring life back to the waterfront.

Cultural Capital and Social Inclusion

According to Marston-Blaauw (2010) there is already a certain degree of interaction between North Vancouver cultural organizations and those from the rest of Vancouver, however, at the moment North Vancouver lacks incentive for artists and/or cultural organizations to remain in or relocate to the community. Currently, those looking for affordable studio space will likely find it elsewhere, as affordable studio space in North Vancouver is scarce (Marston-Blaauw 2010). Though it may be difficult to entice artists from Vancouver to relocate in Lower Lonsdale, retaining and providing increased space for North Vancouver artists should be prioritized. According to Marston-Blaauw (2010:6) there are many local artists that "would benefit from access to simple studios, “dirty” production space and equipment-heavy shop space in their home city". In order to prevent what LeBlanc (2008) refers to as 'a massive art-brain drain': the displacement of cultural capital and creative industries by new middle-class professionals, Lower Lonsdale will need to put in to effect some "culture-retaining" strategies.

Implementing a model similar to Toronto's non-profit organization, Artscape, would be one way of keeping and attracting cultural capital to Lower Lonsdale. This organization works as a "cultural mediator" between artists, developers, and municipal governments, organizing and managing building conversions so artists and cultural organizations have affordable spaces for living, working, exhibiting, and performing (Bunting et al. 2010). Artscape's Distillery Studios provides a good example of a project that could be reinterpreted to help retain cultural capital in Lower Lonsdale. This project converted the derelict Toronto Distillery into retail studios, offices, and performance spaces and has also created an outdoor art market during the summer months (Artscape 2011). Given the ample warehouse space in Lower Lonsdale, converting some of these buildings in to spaces for artists and cultural organizations would be a good strategy for averting the exodus of cultural workers and marginal social groups. By keeping Lower Lonsdale's waterfront accessible to a broad social cross-section and ensuring artist and cultural organization access, the community will avoid creating a homogenized, touristic 'stage set' (Vaz and Jacques 2007:428). After all, " the persons excluded from this spectacularisation process possess perhaps the key to its reversal, which would entail ... popular participation ... and deep acquaintance with urban space" (Vaz and Jaques 2007:250). By ensuring that local artists and cultural workers are a part of the redevelopment picture, Lower Lonsdale will not only increase its chances of becoming a cultural hub, it will also improve its economic vitality in the process.

Inclusion of First Nations in Lot 5’s Development

As previously mentioned, the Mission Indian Reserve sits adjacent to Lonsdale Quay which is the cultural and economic hot-bed of Lower Lonsdale. Currently, the community is segregated from much of the activity surrounding Lower Lonsdale, and as a result, the Reserve has not prospered from the revitalization of the neighbourhood. The urban Aboriginal people living in this community are considerably less well-off than the average household in Lower Lonsdale, and with a growing rate of development being witnessed around them; a greater obstacle to inclusion faces the City of North Vancouver. The City faces a problem of ghettoization and concentrated poverty that can only by fixed by including all residents within the cultural node of the community (Bunting et al. 2010).

The first step to fostering socio-economic development for the Squamish Nations of Lower Lonsdale is to forge a healthy and sustainable relationship between them and the City. The redevelopment of Lot 5 is a perfect means to accomplish this. A key prerequisite for a successful inclusion of Aboriginal peoples in urban areas is an emphasis on showcasing their vibrant culture (Bunting et al. 2010). Therefore, along with showcasing historical artifacts from the Wallace Shipyard, an area dedicated to the Squamish Nations cultural history should be included. This will go a long way in cementing a lasting relationship with the Reserve, and if handled correctly, should increase the community’s interest with public policy and economic welfare.

Another step to include the Mission Indian Reserve in the development of Lot 5 is for the City to encourage involvement by the Reserve. In all council debates, a First Nations presence concerning the development of Lot 5 will ensure the final decision meets the interests of the Reserve. If a mutual feeling of integration is felt by both parties, the Mission Indian Reserve will be able to share in the economic prosperity of Lower Lonsdale.

Avoiding Extending the 'City of Glass'

Vancouver is known for its extensive erection of modern steel and glass towers on podiums. This signature style of Vancouverism is aimed at creating the appearance of neo-traditional row houses, however, its widespread use has created a city that is fairly devoid of architectural interest. According to Pandolfi (2010) the result has been "a post-modern muddle of glass, steel and fake brick". By avoiding extending Vancouver's 'City of Glass', Lower Lonsdale will not only circumvent an architecturally homogenized and unaesthetic landscape, it will also help define the community as a separate and distinct space. Erecting new architecturally pleasing buildings will be part of the process, however making use of current structures will also be a strategy in creating a unique landscape. For example, incorporating the steal frames from the old ships and shipping containers that are sitting on the lot. Also, the previous recommendation of converting vacant and/or derelict warehouses into affordable spaces for artists and cultural organizations, would also help to advance the goal of creating an architecturally diverse and attractive waterfront.

Images

The Shipyards and Lot 5 Today

-

Lot 5 from Esplanade

-

The Coppersmith's Shop (interior)

-

Vancouver Drydock, east of the redevelopment site, remains a working shipyard.

-

The View of the site from the Pier

-

Victory Ship Way from Lonsdale Ave.

-

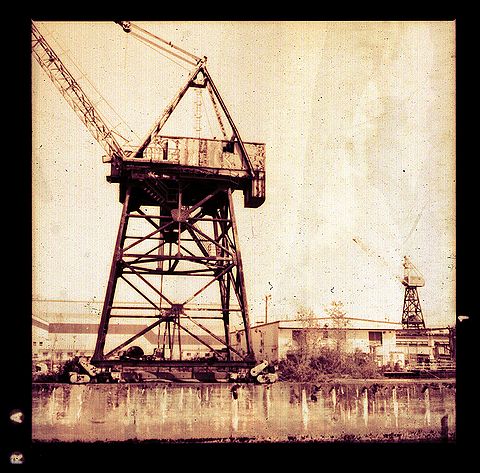

Industrial Memories

The Shipards - during the war and in ruins

-

Aerial View of the Shipyards - 1942

-

The Last of the Victory Ships - 1945

-

The Machine Shop - 1943

-

The Machine Shop - 2006

-

Lot 5 - 2006

-

Quitting Time - 1942

References

1. “North Vancouver History” North Vancouver Museum & Archives, 2010 http://www.northvanmuseum.ca/local.htm

2. “City of North Vancouver 2009 Community Profile Release 2 – Neighbourhoods.” City of North Vancouver, 2009. http://www.cnv.org/c//DATA/3/254/COMMUNITY%20PROFILE%202009%20-%20RELEASE%202%20-%20NEIGHBOURHOODS.PDF

3. “Technical Memorandum No. 1: Investment in Rapid Transit on Urban Land.” Translink, n.d. http://www.translink.ca/~/media/Documents/bpotp/area_transit_plans/south_of_fraser/Technical%20Memorandum%20Phase%202/SOFATP07PHASE2TM1.ashx

4. “A Profile of First Nations, Tribal Councils, Treaty Groups and Associations with Interests within Metro Vancouver and Member Municipalities.” Metro Vancouver, 2012. http://www.metrovancouver.org/region/aboriginal/Aboriginal%20Affairs%20documents/aboriginal-profile.pdf page 20

5. "Social Plan Background Document." City of North Vancouver, Nov. 1997. <http://www.cnv.org/server.aspx?c=3>

6. “History of a Great Shipyard.” City of North Vancouver, 2005. http://www.cnv.org/c/DATA/2/113/HISTORY%20OF%20A%20GREAT%20SHIPYARD.PDF

7. "Pier Development." City of North Vancouver, 2011a. http://www.cnv.org/server.aspx?c=2&i=111

8. “History of the Pier.” City of North Vancouver, 2011b. http://www.cnv.org//server.aspx?c=2&i=113

9. Marshall, R., ed. 2001. Waterfronts in Post-Industrial Cities. London and New York: Spon Press.

10. Bunting T., Filion P., Walker, R., eds. 2010. Canadian Cities in Transition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

11. Bradley, A., T. Hall, and M. Harrison. 2002. 'Selling cities: Promoting new images for meetings tourism', Cities 19, 1:61-70.

12. "Project Waterfront: North Van Design Jam." The North Van Urban Forum. N.p., 2012. Web.

13. Hern, Matt. Common Ground in a Liquid City: Essays in Defense of an Urban Future. Edinburgh: AK, 2010. Print.

14. Pacione, Michael. "Britain's Cities: Geographies of Division in Urban Britain." Google Books. Psychology Press, 1997. Web. Nov. 28 2012. <http://books.google.ca/books?id=jObtFul8XdcC>.

15. Marston-Blauuw, L. "Lower Lonsdale Cultural Facilities Study". 2010. <http://www.artsoffice.ca/database/rte/files/2010%20PROSCENIUM%20REPORT%20(FINAL)--PT_01,%20CONTEXT%20ANALYSIS%20(pp_1-30).pdf>

16. LeBlanc, D. "In Constant Exile, Artists Seek Next Colony", Globe and Mail, November 21, 2008. <http://www.theglobeandmail.com/life/home-and-garden/real-estate/in-constant-exile-artists-seek-next-colony/article663483/>.

17. "Distillery Art Market." Artscape, 2011. <http://www.torontoartscape.org/distillery-art-market>

18. Vaz, L.F., and P.B. Jacques. 2007. 'Contemporary urban spectacularism', in J. Monclus and M. Guardia, eds, Culture, Urbanism and Planning. Aldershot: Ashgate, 241-53.

19. Pandolfi, Christopher. "Vancouver is Everywhere in Monu". 2010. <http://departmentofunusualcertainties.wordpress.com/2010/10/18/vancouverism-is-everywhere-in-monu/>

20. Stevens, Q and K. Dovey. 2004. 'Appropriating the Spectacle: Play and Politics in a Leisure Landscape', Journal of Urban Design 9, 3:351-365.