Course:HIST104/Mehndi

MEHNDI

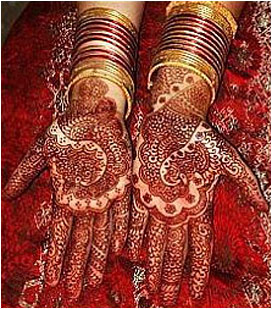

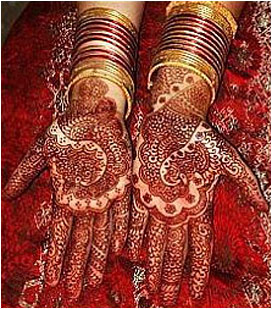

Mehndi or henna tattoos are a long existing form of body modification. Intricate designs are placed on the skin, using a twig like tool, or a bag similar to a pastry tool. The dye is allowed to dry, and then the crust is removed, revealing an inked pattern that will last for a few weeks.

Origins & History

The art of mehndi (or mehandi) has been a long-standing tradition stemming from many ancient cultures dating back as far as about 5,000 years. [1] The practice of henna tattooing predates Islam, scholars suppose that it originated in Egypt, where pharaohs were found entombed with dyed fingernails in the Valley of the Nile. [2] The roots of the mehndi in India are indeterminate, though ancient murals near Mumbai depict a princess with dyed hands, and it’s use in Rajasthan has been dated to 1476. [3] Nevertheless, the exact origin of the mehndi has not been located due to the centuries culture exchange between different groups of people.

Types

There are mainly four different types of Henna patterns. The Middle Eastern style is mostly made of floral patterns similar to the Arabic paintings. The North African style is like the shape of hands and feet using floral patterns. The Indian and Pakistani designs include lines patterns and teardrops. Finally, the Indonesian and Southern Asian styles are a mix if Middle Eastern and India designs using block of color on the very tips of their toes and fingers.

Women's Art

Mehndi designs are done for women by women, particularly for weddings and festivals. Mehndi tattoos are associated with...eroticism, mysticism, privacy, religion, sacred ritual and ceremony, matrimonial and romantic love, folklore and superstition.” [4] The dye sets the person apart from their everyday self, and marks a break with the day-to-day.[5]

Plant

The henna plant is multi-purposed. It is used as a dye, cosmetic, medicine, and is believed by many cultures to have spiritual properties.[6] The dye used in temporary tattoos is made from the dried leaves of the plant, which are crushed into a paste that makes a orange/brown stain, that alters tint depending on the wearers body chemistry. [7] However, it should be noted that in areas of India that do not produce henna plants create mehndi designs using ink made from sandalwood bark or alta ink. [8] Henna powder is derived from a plant (actually a bush), Lawsonia inermis, commonly found in the Middle East and other areas where the climate is hot and dry.[9]

Uses

Henna dye can act as a sunscreen, heals minor skin irritations, has antifungal and antiseptic properties. [10] The mutli-purpose dye is a coolant, reducing body temperature and is used to stave off heat exhaustion. [11] It is also used as a coagulator for open wounds, an antiperspirant, and internally as a treatment for diarrhea, smallpox, leprosy, jaundice and some cancers. [12]

Designs

Mehndi designs (India and Pakistan) are predominantly of birds, plants and ornate arabesques, though henna tattoos vary their designs from culture to culture. [13]

Indian Weddings

Preceding the wedding ceremony, the mehndi ceremony occurs in which females friends and family members paint the palms of the bride, a tradition that began in Northern India and spread after its depiction in the media. [14]As the origins of henna in India are unknown, it has been suggested that mehndi (India and Pakistan) predates Egyptian henna dyes, where women use the dye in almost every festival. [15]The Kama Sutra encourages young women to partake in mehndi for weddings, where in the North, brides rub their skin with honey, herbs and oil to tint it red and yellow; body hair is removed and then the dye is applied. [16] The ceremony is called raatI, or “Night of Henna.” The dye is delivered to the bride from the groom’s family, where the sister-in-law to be decorates the brides hands while guests sing. [17] The designs are placed on both sides of the hands and feet to symbolize devotion and the patterns are then wrapped. [18] The bride does not use her hands for the first month in marriage to preserve the mehndi as long as possible, as it is thought to be a representation of the brides love. [19]

Henna at Other Festivals

In Pakistan, designs are drawn on the belly of the mother when she goes into labour, while in India during the Kava-Chauth festival, wives henna their hands and feet in the wish that the Gods and Goddesses will bestow long lives on their husbands. [20] Mehndi are created with the “fervent wish that the act would engender good fortune , happy results, and good feelings,” and are generally considered lucky or protective. [21] The application itself is considered a meditative and spiritual practice. [22]

Mehndi in the Western World

INTRODUCTION & POPULAR CULTURE

Use by peers was one way the practice was transmitted to a larger audience, as people would visit cultures where henna was traditionally practiced and then bring it back when they returned home.[23] On the other end of the scale, populations have also been influenced by high profile celebrities who have embraced mehndi in the course of their careers and personal life. In the mid-1990s Gwen Stefani of the ska band No Doubt sported bridal-style bindis across her brow [24] in many public appearances, including concert performances and a performance on Saturday Night Live in 1996. In print, actress Liv Tyler appeared on the cover of Vanity Fair in1997 with henna on her hands. [25] But it was perhaps Madonna’s performance on the 1998 MTV music awards that propelled the trend into Western culture. With her henna painted hands and pseudo-Indian dance moves, she performed her song “Frozen” then toured the U.S. and Europe wearing ‘temporary tattoo art’.[26] After this, other high profile figures adopted the practice, including supermodels and fashion designers. Closer to home the singer Alanis Morissette recently made the news when she posted a picture of herself on Twitter with her pregnant stomach decorated with henna.[27]

Other celebrities that have shown off their henna art in public appearances have been Demi Moore, Drew Barrymore, Mira Sorvino, Daryl Hannah, Naomi Campbell, and the Artist Formerly known as Prince.

REASONS FOR POPULARITY IN THE WEST

Mehndi appeals to a Western audience fascinated by and drawn to all forms of body art and body modification but who would be very reluctant to commit to anything permanent, like a tattoo. Mehndi is, in fact, commonly referred to as a henna tattoo – all the cool and style but with none of the needles, pain or permanence. [28] With the pace at which fashions and individual styles for girls and women change, henna’s non-permanence is a selling point. [29]

There is also none of the negative stigma attached to a henna tattoo that is still, even today, associated with tattoos, especially those done on the hands, a popular spot for gang members to record complex codes signifying territory claimed, member’s rank, or rules of the group.[30] Mehndi is very strongly associated with women, as it’s traditionally an art form done by women for other women, so it is seen as a non-threatening and extremely accessible way for Western women to change the outward appearance of their body.

Mehndi is also perceived by Western audiences as having a very strong and vital spiritual component which taps directly into the Western culture’s desire to connect with a force that is somehow considered primal and universal in order to lead lives that have deep meaning beyond our it’s materialistic and capitalist world. The hands certainly have long figured prominently in many religious rituals, such as prayer rites[31] and the Muslim religion itself views the application of mehndi as sacred.[32] In traditional body painting, paints were made out of earth, and as many religions centred around the earth as a spiritual place, using body paints was considered a sacred activity.[33] In using mehndi to connect to this deeper spirituality, Western audiences use their bodies as vehicles for self-realization [34] and the attachment to the rites and rituals of other cultures is an authentic struggle to awaken what they feel to be lost within themselves. [35]

In this process, Westerners also seek to define their own individuality. Mehndi is a way in which one, quite literally, marks oneself as different, using the designs and patterns as a means of advertising their uniqueness to the greater community and culture. [36] The use of cosmetics in general is a way in which one uses adornment to put forth an ideal self. [37] Mehndi furthers this by incorporating a spiritual and even divine element into the persona that is traced by the design and which one displays for everyone to see.

WESTERN EVOLUTION OF MEHNDI

Mehndi is strongly rooted in traditional and ritualistic environments and purposes, some of which have remained in Western culture. Its use for weddings or pregnancy, for example, is still popular amongst women. But in other ways, the traditional roots of mehndi have been modified, adapted or outright changed either to suit a Western audience or simply because the original meaning and intent was adapted and expanded. The most obvious example of this can be found in where mehndi is applied. Traditionally it was only for the hands and feet because in cultures where henna is traditionally practiced showing other parts of the body other than the hand and feet is discouraged for women.[38] In the West, mehndi is also found on the upper arms, across the back, on stomachs, and other areas that can be left uncovered. [39]

In terms of design, mehndi is characterized by very intricate motifs which varied from culture to culture: Middle Eastern countries favour floral patterns that recall Arabic art, while North Africa incorporates more geometric forms and Southeast Asia often uses solid blocks of colour on the fingertips and toes.[40] In the West, designs often resemble traditional tattoo designs – single motifs depicting Celtic or tribal patterns, or a word rendered in a foreign script.[41] One design in particular, has emerged in the West - that of an asymmetrical vine-like flower that winds around the wrist and down the index finger. This particular design has, in fact, found its way back to India and can be seen on the hands of Bollywood stars and local brides. [42]

EXTENDED FORMS OF MEHNDI

Graphic design:

CD covers, clothing and high fashion, ad campaigns[43]

Fine art: contemporary visual artists & artists who specialize in body or face painting[44]

Ritual and special occasions: weddings, engagements, pregnancy, after the birth of a child[45]

IMPLICATIONS & RAMIFICATIONS OF MEHNDI IN WESTERN POPULAR CULTURE

The incorporation of mehndi into popular culture has both positive and negative consequences. In terms of the positive, mehndi represents the international sharing of artistic ideas and processes, and its popularity is representative of an appreciation for the traditional arts of other cultures, particular that which is so strongly identified with and connected to women. [46] For a South Asian population, there is also the satisfaction in seeing what were previously hidden markers of ethnicity enter the public sphere.[47]

But that comes with a price. In terms of the negative, mehndi’s popularity has meant that its tools, designs and practice have become commodified with corporations marketing and selling do-it-yourself henna kits that can be ordered online or found at chain stores such as Urban Outfitters.[48] As for henna services, American henna tattoo artists charge much more than would be charged by a woman in India for the same service [49] The fact that the artists hail from diverse ethnic backgrounds from all over the U.S.[50] shows that non-Orientals use it as a business opportunity in the West. Temporary body art has grown into a business that revenues $100 million per year and demographically, teenagers are the most abundant supporters of this business.[51] It is an ironic twist, then, that as Westerners search for their own spiritual paths away from the aggressively commercialized culture, they find themselves on the same path with respect to the mehndi traditions that are so valued for being above such commercialization. This cultural appropriation portends a loss of henna’s spiritual, ritual and cultural significance.[52] For some, this means the potential for their own culture to become muddied as influence from popular Western culture flows back to the Eastern cultures where mehndi originated.[53] This raises questions of authenticity and who has the ‘right’ to practice mehndi?

In reality, mehndi itself is a hybridization, a product of its affiliation with multiple communities, rather than the product of two or more discrete cultural strands.[54] This can be seen particularly in its range of design motifs and patterns that span countries and populations. While there will always be those who believe that mehndi should only be worn by those who understand its cultural significance, the reality is that all exist in multiple social contexts. Traditions are in a constant state of change as interactions of communities occur on a local and global scale. Some traditions will be lost, some meanings will change, but at the same time new traditions and meanings will be set down which will be no less significant or potent to the individual and the greater culture.

Henna and Religion

The practice of making Henna into a paste then applying the paste to one’s body is widely involved in many Religious ceremonies around the world. The application of Henna to the body can have many different meanings depending on which Religion the worshipper belongs to. Henna was used in the earliest forms of religious worship dating back to the Neolithic People of the 7th Century in Catal Huyukm (now modern day Turkey), where Henna was applied to the worshippers hands in association to their fertility goddess. [55] Paganism was very popular among the Neolithic people, a Pagan was somebody who religiously worshipped many gods/ goddesses and deities. As Paganism spread throughout the world so did the ritual’s involving the Henna plant being applied to the body. So when Islam arrived in the middle east Henna was already widely being used as part of daily worship to the gods.

Islam

Henna was part of the culture of Islam and as the Religion of Islam spread throughout the Middle East and northern Africa so did the use of Henna. [56] In the Quran the main religious text of Islam, Henna is mentioned several times as a perfume and also a plant to heal wounds. The Henna flower was called nor n-nbi, “the light of the Prophet” [57] The application of Henna paste was also originally used in the “Id al-adha” the Muslim feast of Sacrifice, when the prophet Mohammed sacrificed a ram in remembrance of Abraham he applied Henna and Kohl to the ram and his own hands. [58] This was done to purify and oust evil spirits who intend to befoul the sacrifice, the Henna paste was poured into the mouth of the animal, before the throat was cut. [59] In Islam, the use of henna is “Sunnah,”. Using Henna is something that Mohammed himself used. Within the Religion of Islam one can also find many images of women with henna-stained fingertips, feet and hands these images first surfaced around the ninth century. Lastly Henna tattoos are gaining popularity among Muslim’s as permanent tattoos are currently forbidden.

Judaism

Like most other religions, Judaism can involve the use of Henna tattoos during marriage festivities, the marriage of a man and woman is considered a very religious experience and Henna is applied to the bride the night before the marriage to protect against the “evil eye” [60] The evil eye is discussed in the holy book the Talmud and is believed to be the reason for sickness tragedy and pain in the world. [61] It is also believed that “The Henna Ceremony” which includes the hands and feet of the bride being painted in Henna shows her new bond between God and the soon to be bride. In addition, if a woman believed the Evil eye had been casted on her, she could have a Henna pattern drawn on her to provide protection. Henna designs are also found in images associated to Judaism, for example on the floor of the Beth Alpha Synagogue in Galilea there is a image of Gods “hennaed” hand extending out to Abraham’s Knife. [62]

Christian

Henna use in Christian Religion is very limited, however a reference to Henna is found in the Bible, Song of Soloman 1:14. “A bundle of myrrh is my beloved unto me; he shall lie all night between my breasts. My beloved is unto me as a cluster of camphire in the vineyards of En-gedi”. In this passage many scholars believe “camphire” is Henna but the mentioning of Henna from the Bible is referring to the plant and not the application of the paste onto the skin in the form of a design. [63]

Hinduism

Just like in Judaism, Henna can also be found in many Hindu images, if one looks at the goddess Lakshmi, a Henna design is found in the palm of her hand. It is believed that Hindu woman who use Henna designs on themselves can feel the presences of Lakshmi who is the goddess of prosperity. [64]

Egypt:

It has the evidence that it has been found that henna was used to stain the fingers and toes of Pharaohs earlier to mummification. The mummification process took many days and as the Egyptians were diligent in planning their rebirth after their death, they became quite fanatical in the preservation process. The Egyptians believed that body art ensured their recognition into the afterlife and therefore used Mehendi to identify them. [65]

References:

- ↑ Karen L.Hudson,Introduction to Henna and Mehndi,"[1]",

- ↑ Pasekoff Weinberg, Norma. Henna from head to toe. (Vermont: Storey Books, 1999), 1.

- ↑ Pasekoff Weinberg, Norma. Henna from head to toe. (Vermont: Storey Books, 1999), 3.

- ↑ Maira, Suniana. “Temporary Tattoos: Indo-chic Fantasies and Late Capitalist Orientalism.” Meridians 3 (2002): 134. Web. Nov. 7 2010.

- ↑ Sanders, Clinton R. Customizing the Body: The Art and Culture of Tattooing. (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1989), 4.

- ↑ Pasekoff Weinberg, Norma. Henna from head to toe. (Vermont: Storey Books, 1999), 2.

- ↑ Pasekoff Weinberg, Norma. Henna from head to toe. (Vermont: Storey Books, 1999), 2.

- ↑ Fabius, Carine. Mehndi: The Art of Henna Body Painting. (New York: Three Rivers Press, 1998), 18-21.

- ↑ Karen L.Hudson,Introduction to Henna and Mehndi,

- ↑ Pasekoff Weinberg, Norma. Henna from head to toe. (Vermont: Storey Books, 1999), 15-17..

- ↑ Pasekoff Weinberg, Norma. Henna from head to toe. (Vermont: Storey Books, 1999), 17.

- ↑ Fabius, Carine. Mehndi: The Art of Henna Body Painting. (New York: Three Rivers Press, 1998), 25.

- ↑ Pasekoff Weinberg, Norma. Henna from head to toe. (Vermont: Storey Books, 1999), 22.

- ↑ Kolanad, Gitanjali. Culture Shock: India. (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish, 2005), 82.

- ↑ Nichols, Pamela. The Art of Henna: The Ultimate Body Art Book. (Berkeley: Celestial Arts, 2002), 31.

- ↑ Nichols, Pamela. The Art of Henna: The Ultimate Body Art Book. (Berkeley: Celestial Arts, 2002), 31.

- ↑ Nichols, Pamela. The Art of Henna: The Ultimate Body Art Book. (Berkeley: Celestial Arts, 2002), 38.

- ↑ Nichols, Pamela. The Art of Henna: The Ultimate Body Art Book. (Berkeley: Celestial Arts, 2002), 31.

- ↑ Fabius, Carine. Mehndi: The Art of Henna Body Painting. (New York: Three Rivers Press, 1998), 17.

- ↑ Nichols, Pamela. The Art of Henna: The Ultimate Body Art Book. (Berkeley: Celestial Arts, 2002), 51.

- ↑ Fabius, Carine. Mehndi: The Art of Henna Body Painting. (New York: Three Rivers Press, 1998), 15-17.

- ↑ Fabius, Carine. Mehndi: The Art of Henna Body Painting. (New York: Three Rivers Press, 1998), 24.

- ↑ Reid-Walsh, J., C.A. Mitchell (2007). Henna. In Girl Culture [Two Volumes]: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, CA : Greenwood. Retrieved from http://ebooks.abc-clio.com/reader.aspx?isbn-9780313084447&id=GR3908-4056, 2010-Nov-18. pp 350

- ↑ Maira, Sunaina (2000). Henna and Hip Hop: The Politics of Cultural Production and the Work of Cultural Studies. In Journal of Asian American Studies, Vol. 3, No. 3, October 2000. pp 341

- ↑ Maira, Sunaina (2000). Henna and Hip Hop: The Politics of Cultural Production and the Work of Cultural Studies. In Journal of Asian American Studies, Vol. 3, No. 3, October 2000. pp 341

- ↑ Maira, Sunaina (2000). Henna and Hip Hop: The Politics of Cultural Production and the Work of Cultural Studies. In Journal of Asian American Studies, Vol. 3, No. 3, October 2000. pp 341

- ↑ http://thestir.cafemom.com/pregnancy/112760/celebrate_your_pregnancy_like_alanis

- ↑ Murray, Samantha. (2008). Mehndi. In V. Pitts-Taylor (Ed.), Cultural Encyclopedia of the Body, Santa Barbara, CA : Greenwood. Retrieved from http://ebooks.abc-clio.com/reader.aspx?isbn-9781567206913&id=GR4145-2374, 2010-Nov-18. pp 276

- ↑ Reid-Walsh, J., C.A. Mitchell (2007). Henna. In Girl Culture [Two Volumes]: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, CA : Greenwood. Retrieved from http://ebooks.abc-clio.com/reader.aspx?isbn-9780313084447&id=GR3908-4056, 2010-Nov-18. pp 349

- ↑ Jolley, M. (2008). Cultural History of the Hands. In V. Pitts-Taylor (Ed.) Cultural Encyclopedia of the Body, Santa Barbara, CA : Greenwood. Retrieved from http://ebooks.abc-clio.com/reader.aspx?isbn-9781567206913&id=GR4145-2324, 2010-Nov-18. pp 268

- ↑ Jolley, M. (2008). Cultural History of the Hands. In V. Pitts-Taylor (Ed.) Cultural Encyclopedia of the Body, Santa Barbara, CA : Greenwood. Retrieved from http://ebooks.abc-clio.com/reader.aspx?isbn-9781567206913&id=GR4145-2324, 2010-Nov-18. pp 271

- ↑ Murray, Samantha. (2008). Mehndi. In V. Pitts-Taylor (Ed.), Cultural Encyclopedia of the Body, Santa Barbara, CA : Greenwood. Retrieved from http://ebooks.abc-clio.com/reader.aspx?isbn-9781567206913&id=GR4145-2374, 2010-Nov-18. pp 275

- ↑ DeMello, Margo. (2007). Body Painting. In Encyclopedia of Body Adornment. Santa Barbara, CA : Greenwood. Retrieved from http://ebooks.abc-clio.com/reader.aspx?isbn-9780313064050&id=GR3695-904, 2010-Nov-18. pp 28-40

- ↑ Sherr, Leslie. “Henna Mania”, Print (New York, N.Y.), 54 No. 3, My/June 2000, pp. 64

- ↑ Sherr, Leslie. “Henna Mania”, Print (New York, N.Y.), 54 No. 3, May/June 2000, pp. 62-7

- ↑ Sherr, Leslie. “Henna Mania”, Print (New York, N.Y.), 54 No. 3, May/June 2000, pp. 65

- ↑ Spurgas, Alyson. (2008). History of Makeup Wearing. In V. Pitts-Taylor (Ed.) Cultural Encyclopedia of the Body, Santa Barbara, CA : Greenwood. Retrieved from http://ebooks.abc-clio.com/reader.aspx?isbn-9781567206913&id=GR4145-1424, 2010-Nov-18. pp 142

- ↑ DeMello, Margo. Foot and Shoe Adornment. In Feet and Footwear: A Cultural Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, CA : Greenwood. Retrieved from http://ebooks.abc-clio.com/reader.aspx?isbn-9780313357152&id=GR5714-1354, 2010-Nov-18. pp 133

- ↑ Reid-Walsh, J., C.A. Mitchell (2007). Henna. In Girl Culture [Two Volumes]: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, CA : Greenwood. Retrieved from http://ebooks.abc-clio.com/reader.aspx?isbn-9780313084447&id=GR3908-4056, 2010-Nov-18. pp 349

- ↑ Murray, Samantha. (2008). Mehndi. In V. Pitts-Taylor (Ed.), Cultural Encyclopedia of the Body, Santa Barbara, CA : Greenwood. Retrieved from http://ebooks.abc-clio.com/reader.aspx?isbn-9781567206913&id=GR4145-2374, 2010-Nov-18. pp 275

- ↑ Shukla, Pravina (2008). Henna Art/Mehndi. In L. Locke, T.A. Vaughan,, P. Greenhill (Ed.). Encyclopedia of Women’s Folklore and Folklife. Santa Barbara, CA : Greenwood. Retrieved from http://ebooks.abc-clio.com/reader.aspx?isbn=9780313088131&id=GR4050-4364. 2010-Nov-17. pp 299

- ↑ Shukla, Pravina (2008). Henna Art/Mehndi. In L. Locke, T.A. Vaughan,, P. Greenhill (Ed.). Encyclopedia of Women’s Folklore and Folklife. Santa Barbara, CA : Greenwood. Retrieved from http://ebooks.abc-clio.com/reader.aspx?isbn=9780313088131&id=GR4050-4364. 2010-Nov-17. pp 298

- ↑ DeMello, Margo. (2007). Body Painting. In Encyclopedia of Body Adornment. Santa Barbara, CA : Greenwood. Retrieved from http://ebooks.abc-clio.com/reader.aspx?isbn-9780313064050&id=GR3695-904, 2010-Nov-18. pp 40

- ↑ DeMello, Margo. (2007). Body Painting. In Encyclopedia of Body Adornment. Santa Barbara, CA : Greenwood. Retrieved from http://ebooks.abc-clio.com/reader.aspx?isbn-9780313064050&id=GR3695-904, 2010-Nov-18. pp 40

- ↑ Murray, Samantha. (2008). Mehndi. In V. Pitts-Taylor (Ed.), Cultural Encyclopedia of the Body, Santa Barbara, CA : Greenwood. Retrieved from http://ebooks.abc-clio.com/reader.aspx?isbn-9781567206913&id=GR4145-2374, 2010-Nov-18. pp 276

- ↑ Reid-Walsh, J., C.A. Mitchell (2007). Henna. In Girl Culture [Two Volumes]: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, CA : Greenwood. Retrieved from http://ebooks.abc-clio.com/reader.aspx?isbn-9780313084447&id=GR3908-4056, 2010-Nov-18. pp 350

- ↑ Maira, Sunaina (2000). Henna and Hip Hop: The Politics of Cultural Production and the Work of Cultural Studies. In Journal of Asian American Studies, Vol. 3, No. 3, October 2000. pp 351-2

- ↑ Reid-Walsh, J., C.A. Mitchell (2007). Henna. In Girl Culture [Two Volumes]: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, CA : Greenwood. Retrieved from http://ebooks.abc-clio.com/reader.aspx?isbn-9780313084447&id=GR3908-4056, 2010-Nov-18. pp 350

- ↑ Maira, Sunaina (2000). Henna and Hip Hop: The Politics of Cultural Production and the Work of Cultural Studies. In Journal of Asian American Studies, Vol. 3, No. 3, October 2000. pp 13

- ↑ Maira, Sunaina (2000). Henna and Hip Hop: The Politics of Cultural Production and the Work of Cultural Studies. In Journal of Asian American Studies, Vol. 3, No. 3, October 2000. pp 7

- ↑ Basas, Carrie Griffin (2007). Henna Tattooing: Cultural Tradition Meets Regulation. 62 Food & Drug L.J. 779

- ↑ Sherr, Leslie. “Henna Mania”, Print (New York, N.Y.), 54 No. 3, My/June 2000, pp. 64

- ↑ Maira, Sunaina (2000). Henna and Hip Hop: The Politics of Cultural Production and the Work of Cultural Studies. In Journal of Asian American Studies, Vol. 3, No. 3, October 2000. pp 351-2

- ↑ Maira, Sunaina (2000). Henna and Hip Hop: The Politics of Cultural Production and the Work of Cultural Studies. In Journal of Asian American Studies, Vol. 3, No. 3, October 2000. pp 351-2

- ↑ Mellaart, James; “Catal Huyuk, A Neolithic Town in Anatolia” McGraw Hill Book Company, New York, 1967.

- ↑ . Trimingham, J. Spencer; “Islam in West Africa” Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1959

- ↑ Westermarck, Edward, Ritual and Belief in Morocco. (London: Macmillan and Company, 1926), 113

- ↑ Hammoudi, Abdellah. The Victim and Its Masks, an Essay on Sacrifice and Masquerade in the Maghreb. (Chicago and London, 1993), 186

- ↑ Hammoudi, Abdellah. The Victim and Its Masks, an Essay on Sacrifice and Masquerade in the Maghreb. (Chicago and London, 1993), 116

- ↑ http://www.torah.org/learning/women/class9.html#

- ↑ http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Judaism/evil_eye.html.

- ↑ Cartwright-Jones, Catherine. Id al-Adha: The Ecological and Nutritional Impact of the Muslim Feast of Sacrifice, and the Significance of Henna in this Sacrifice. (Stow: Tapdancing Lizard, 2002), 3

- ↑ http://www.biblediscovered.com/biblical-women-of-israelites/ancient-perfumes-and-aromatic-oils/

- ↑ http://hinduism.about.com/od/matrimonial1/a/mehendi.htm

- ↑ http://www.asian-women-magazine.com/mehndi/history-mehndi.php