Women in Canadian Politics

Background

Canadian women have made many advances and developments in the past decade or so - Women were granted the right to vote nearly 60 years ago. Two national parties have had female leaders, Rita Johnston of British Columbia and Catherine Callbeck of Prince Edward Island. Kim Campbell became the first female Prime Minister. With these strides considered, many long standing issues of culture, discrimination and advancement remain in play within the House of Commons and political parties which continue to put women at a systematic and societal disadvantage.

Women represent 50% of the population, however they only hold 25% of the seats in the Canadian House of Commons. In the 2015 election, women held only 88 of the 338 seats, a measly 26% representation. Though the fundamental ideology underlying democracy is the equality of opportunity for all citizens, history has proven this to be untrue for women currently serving or aiming to enter the political realm in Canada. On an international scale, Canada also continues to fall short of the 30% female representation threshold recommended by the United Nations with 26.3% female representation. In fact, we fall behind 61 developing and developed countries in terms of representation, including but not limited to Afghanistan, Uganda, Rwanda and the UK. The gender gap can be attributed to a combination of culture, policies and history, ultimately shaping the current "Old Boys Club" that continues to persist.[1]

It is important to note that gender experiences differ based on individual circumstances (such as working class women, women in different cultural contexts and women of colour) [2]. In other cases, the barriers to entry may not be limited to simply gender, but rather an intersection of one or more forces, including but certainly not limited to race, religion and sexuality. Though it is undoubtedly difficult for all women to get situated within politics, those from indigenous, radicalized and/or queer groups face additional barriers.

Women's Role in Parties

Women have long been seen to do the administrative grunt work during election campaigns. Although these roles have further developed to paying positions within the executive and beyond, according to Canadian data, women continue to dominate administrative positions within executives. “ Approximately two thirds of constituency secretaries in which a thorough count has been conducted were female, and this continues to be the case regardless of level of government (federal versus provincial), geographic location or time period”(). As such, women are granted the opportunity to do the work men refuse to do in party and riding politics. There is an unofficial rule coined “the higher, the fewer” which contends that the higher in the party one moves, the less women are to be seen (50) [3].

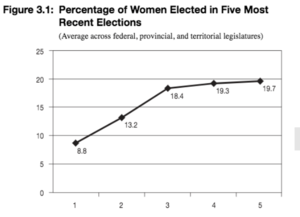

As party politics evolved, women were granted the opportunity to run by individual parties. However, they were often "sacrificial lambs" in ridings seen to be unwinnable by the respective party and are simply used as a means of presenting the party in a more favourable light. Though Canada has progressively been increasing the percentage of elected women in the past several elections, it remains up to parties to increase the number of female candidates in competitive ridings [4]. Even as women are elected, they do not represent all women as most politicians are white, middle-upper class, heterosexual, educated and able bodied. A fundamental gendered division of labour that suggests a culture (both within politics and beyond) in which women are always at a disadvantage to men inhibits women from advancing to higher positions and larger roles.

Gendered Division of Societal Roles

One of the reasons women do not enter politics in the same capacity that men do is attributed to the division of social roles and gendered stereotypes which contend that women are not capable of holding office. Society often defines women as placing a larger importance on marital or familial ties than males. As such, there is an underarching tension between women's rights and their societal, moral and biological obligations (28) [5] ; they are expected by society to spend a considerable amount of time on their personal lives, therefore making them less desirable candidate options by political parties. However, it is worth noting that this again does not apply to all women - women with higher economic status are able to hire help or afford to forfeit wages, thereby removing them from such barriers.

Women's Voting Preferences

Since winning the right to vote, women have undoubtedly taken every opportunity to involve themselves in the voting process. Varied behaviours, traits and attitudes, both as individuals and as a collective gender group, on issues have created a gender gap with respect to voting preferences. Their reliance on government subsidies, pink-collar occupations and role of the role of feminism in distinguishing political ideologies contribute largely to gendered patterns [6].

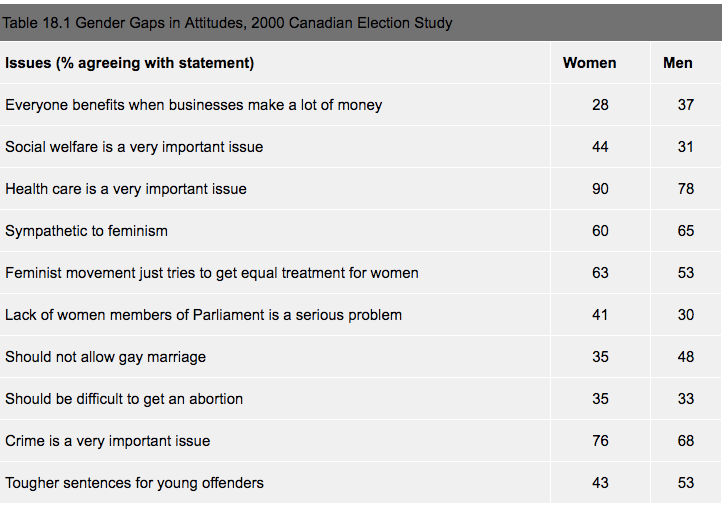

Table 18.1 shows gendered attitudes on multiple issues of importance in the 2000 Canadian election. Certain opinions, including opinions on social services, are deeply rooted in structural gaps that remain commonplace. For example, Canadian women continue to earn lower income than men, have lower (on average) high school completion rates and inhibit occupations dominated largely by women. These systematic problems result in women relying on greater state funded programs and services (as evident in the table) to a greater extent than men. Thus resulting in a larger proportion of women voting for right leaning parties, whereas a larger proportion of men tend to vote for left leaning parties.

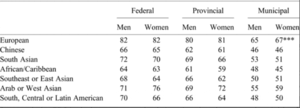

The voter turnout between men and women is nearly identical, however when sampling women across different ethnic groups, there appears to be a considerable difference in voter turnout. As per Table 1 [7], one can see that individuals of European backgrounds are more likely to vote than their radicalized counterparts. As such, one is able to see the impact of race and immigration on women's voting preferences and the continued dominance of eurocentricitity within the voting system rooted in the socialized norms and gendered values within and across communities [8]

References

- ↑ Women in Politics 2017 Map.” UN Women, United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (UN Women), 2017, www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2017/4/women-in-politics-2017-map

- ↑ Trimble, Linda J., and Jane Arscott. Still Counting: Women in Politics across Canada. Univ of Toronto Press, 2008.

- ↑ Harell, Allison. “Intersectionality and Gendered Political Behaviour in a Multicultural Canada.” Canadian Journal of Political Science, vol. 50, no. 02, 28 June 2017, pp. 495–514., doi:10.1017/s000842391700021x.

- ↑ Trimble, Linda J., and Jane Arscott. Still Counting: Women in Politics across Canada. Univ of Toronto Press, 2008.

- ↑ Kealey, Linda, and Joan Sangster. Beyond the Vote: Canadian Women and Politics. University of Toronto Press, 1989.

- ↑ O'Neill, Brenda, and Lisa Young. "Women in Canadian Politics." The Oxford Handbook of Canadian Politics. : Oxford University Press, 2010-04-08. Oxford Handbooks Online

- ↑ Harell, Allison. “Intersectionality and Gendered Political Behaviour in a Multicultural Canada.” Canadian Journal of Political Science, vol. 50, no. 02, 28 June 2017, pp. 495–514., doi:10.1017/s000842391700021x

- ↑ Harell, Allison. “Intersectionality and Gendered Political Behaviour in a Multicultural Canada.” Canadian Journal of Political Science, vol. 50, no. 02, 28 June 2017, pp. 495–514., doi:10.1017/s000842391700021x.