GRSJ224/Orientalism in India

Introduction

Edward Said, academic and political activist, criticizes Orientalist essentialism in his influential book Orientalism, where he challenges how Western societies place themselves as superior counterparts from Eastern societies. Although Said focuses on European views on the Arab Middle East, his critique of Orientalism is widely applicable to other non-Western regions, such as India (11)[1]. In its present state, India exercises Occidentalism, or Self-Orientalism, to position itself for reputable gains. For example, India’s practice of Self-Orientalism is currently aiding in a major push for reform. In particular, Indian women have allowed Western women to become ambassadors of global feminism, which has made female empowerment a hot topic in India (Liddle and Rai, 495)[2]. Moreover, Self-Orientalism in India has a lot of economic value. For example, Self-Orientalization in India allows for greater tourism, as the country markets itself as a romantic, tribal, and antiquated destination for western tourists (Islam, 224) [3]. Moreover, fashion enthusiasts travel to India for Indian fashion and other beauty industries (Islam, 222) [3]. Due to this, Western fashion trends have now become popular among middle-class Indians, because Indians look towards their Western counterparts for influence. This shows us that Westerners have authority over Eastern culture.

However, as mentioned in Rajiv Malhotra’s The Battle For Sanskrit, there are a multitude of consequences involved in Self-Orientalism (Malhotra, 12) [4]. Malhotra refers to Orientalism views on India as a dangerous phenomenon as it devalues Indian scholars and narratives (Jagannathan) [5]. This page will examine the relevance of Edward Said’s Orientalism in India and how the country practices self-Orientalization for its benefits while damaging its reputation.

Said’s Critique on Orientalism

Edward Said was an influential scholar in the late 20th century who created the foundation of post-colonial studies and changed the viewpoints of the Middle East. In his published work Orientalism, Said argued that North American and European scholarly research about the East was erroneous, and misleading. This was because Western scholars in North America and Europe confined the Eastern part of the world as an exotic and mysterious region without properly understanding it (Said, 73) [1]. Due to the authority of Western scholars, and how much Eastern culture deviated from their own culture, their viewpoints felt reasonable, despite their biased perspective. Furthermore, Said also believed the West may be purposely positioning themselves as far more superior to their Eastern counterparts for political gain and to colonize Eastern countries. Said’s viewpoint challenged the views of many at the time, however, due to his powerful argument, Orientalism’s definition has changed significantly in present day, now pertaining to a patronizing attitude towards Eastern culture.

Orientalism in India

Although Said’s focus was on European Orientalism on the Arab Middle East, his critique on Orientalist discourse is relevant to other Eastern parts of the world as well, such as India. Said briefly mentions India in his academic work, stating how British scholars and political economists such as John Stuart Mill, claimed India was racially and socially inferior and would not be able to create and hold a proper government.

In present day, Western societies have become inspired by India’s ‘rich cultures’ and ‘ancient wisdom,’ but also look down on India’s ‘absurd religions’ and ‘slow progression’ (Said, 1) [1]. These positive and negative prejudices and stereotypes on India have shaped its social and economic elements for the better.

Scholars and Academics

Rajiv Malhotra, influential author and Hindu activist, believes Indian studies, including its history and culture, has become overtaken by North American academics. In his book The Battle for Sanskrit, Malhotra claims these academics unknowingly disrespect India’s traditions as it devalues Indian scholars and narratives and Indian culture as a whole. When North American academics dissect Indic traditions, for example, the research could be too detached from its living tradition and sacred roots (Jagannathan) [5]. Additionally, India provides the West with resources and acknowledgment, while Indian scholars and academics struggle with the same recognition and resources (Jagannathan) [5].

Feminism

Feminist issues in India such as honor killings, unfairness in caste systems, and forced arranged marriages have severely stunted the country’s social and economic potential (Jani and Felke) [6]. India’s practice of Self-Orientalism is currently aiding in a major push for reform. Indian women have allowed Western women to become ambassadors of global feminism, which has made female empowerment a hot topic in India (Liddle and Rai, 496) [2].

However, North American feminists have continuously looked down on the women of India, claiming they are helpless and unable to create change due to strict culture. For example, Katherine Mayo, well-known feminist journalist, claimed in her book Mother India that India had “little ambition to raise or to change actual living conditions” and “they are content with their mud huts…rather than work harder for more food” (Mayo, 74) [7]. Mayo also describes Indian women as weak victims of social discourses and therefore are too ignorant to solve feminist issues (Mayo 75) [7]. Even though Indian women are following Western feminism as inspiration to their own social fallbacks, it is apparent that Indian feminism is disrespected among some Western feminists. Therefore, universally, the people of India are looked down upon for their ‘barbaric’ and ‘archaic’ livelihoods (Mayo, 74) [7].

Tourism

Self-Orientalization in India allows for greater tourism, which therefore provides a lot of economic value for the country (Nash, 467) [8]. India markets itself as a romantic, tribal, and antiquated destination because this is how Western tourists imagine India (Said, 11) [1]. India’s National Museum, for example, shares similar Oriental elements to entice the Western tourist, and seldom displays modern art outside of traditional Indian culture (National Museum, New Delhi) [9]. Even though India’s tourism industry takes advantage of Orientalist discourse, its tweaks to change their identity to fit Western viewpoints hinders their independence and reinforces colonial discourse (Nash, 468) [8].

Fashion

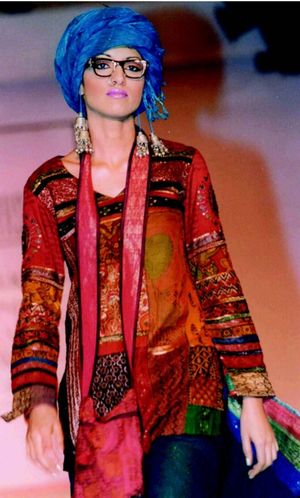

Fashion studies have always focused on a Western society’s perspective (Nagrath, 366) [10]. Indian fashion designers learn to “internalize this oriental glaze…” (Nagrath, 362) [10]. Indian fashion designers have taken this discourse to their advantage by self-Orientalizing fashion and focusing on traditional Indian garments to appear ‘exotic’ (Nagrath, 362) [10]. This has helped India become a fashion influencer, as Western fashion revolves around Indian-influenced fashion such as the ‘hippie chic’ look as well as luxury clothing and accessories such as silks, jewelry and shawls (Nagrath, 367)[10].

However, India’s willingness to conform to Oriental stereotypes in the fashion industry harms the country in the long run. For example, fashion stylist Sabyasachi Mukherji was praised for his Indian-inspired fashion at Fashion Week 2002 (Nagrath, 362) [10]. His work was described as ‘fresh’ and ‘innovative,’ however, his collection consisted of modern Indian fashion (Nagrath, 362) [10]. Therefore, India’s fashion radar is ignored and insignificant until Western society promotes it. Moreover, during India’s Fashion Week in 2001, its press releases explained, “India has long been the source of beautiful fabrics and embroidery. But its own high-fashion design industry has been virtually nonexistent-- until now” (Newsweek International). This statement supports the idea that Indian fashion required Western acceptance to be recognized.

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Said, Edward W. Orientalism. Vintage Books, 2004.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 Liddle, Joanna, and Shirin Rai. “Feminism, imperialism and orientalism: the challenge of the ‘Indian woman’.” Womens History Review, vol. 7, no. 4, 1998, pp. 495–520., doi:10.1080/09612029800200185.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 Islam, Nazrul. “New Age Orientalism: Ayurvedic ‘wellness and spa culture’.” Health Sociology Review, May 2012, pp. 1339–1360., doi:10.5172/hesr.2012.1339.

- ↑ Malhotra, Rajiv. The battle for Sanskrit: is Sanskrit political or sacred, opressive or liberating, dead or alive? HarperCollins Publishers, 2016.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 5.2 Jagannathan, R. “'American Orientalism' As The New Macaulayism, And What We Need To Do About It.” Swarajya Read India Right ATOM, 26 Jan. 2016, swarajyamag.com/culture/american-orientalism-as-the-new-macaulayism-and-what-we-need-to-do-about-it.

- ↑ Jani, Nairruti, and Thomas P Felke. “Gender bias and sex-Trafficking in Indian society.” International Social Work, vol. 60, no. 4, 2015, pp. 831–846., doi:10.1177/0020872815580040.

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 7.2 Mayo, Katherine. Mother Earth. University of Michigan Press, 2000.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 Nash, Dennison. “The Context of Third World Tourism Marketing.” Annals of Tourism Research, vol. 31, no. 2, 2004, pp. 467–469., doi:10.1016/j.annals.2003.12.012.

- ↑ “About the National Museum.” National Museum, New Delhi, www.nationalmuseumindia.gov.in/collections.asp.

- ↑ Jump up to: 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Nagrath, Sumati. “(En)Countering Orientalism in High Fashion: A Review of India Fashion Week 2002.” Fashion Theory, vol. 7, no. 3-4, 2003, pp. 361–376., doi:10.2752/136270403778052005.