Vocabolario History

The Accademia della Crusca is an Italian academy established in the city of Florence, Italy in 1582 in order to purify and maintain the Tuscan language. [1] The Academy was founded most notably by Giovan Battista Deti, Anton Francesco Grazzini, Bernardo Canigiani, Bernardo Zachini, and Bastiano de’ Rossi. [2]

At the time, the Tuscan language was the literary language of the Italian Renaissance, but was also used widely in school, politics and press as a spoken language. [3] However, the use of Tuscan as a spoken dialect varied greatly as each place had its own vernacular (or slang). This led to various different definitions, spellings, and phrases being used for the same word, causing a large disproportion of understanding. With the growth of the Tuscan language, there appeared to be many problems with the words being spoken: too many inappropriate words, variants, or even words that weren’t really “Tuscan”. This was seen to occur when the idea of a unified Italian nation arose with a united language, causing a decrease in local dialects. [4] However, local dialects were commonly used as a driving force for the culture of the locals, [5] and it was this that led to the development of the Academy, which was compiled of what became known as lexicographers, or those who compile dictionaries in order to maintain the structure and knowledge of languages, and the age of dictionaries had begun, which saw lexicographers from around the world attempting to stop the spread of word variations in order to create a concrete list of acceptable words. [6]

Before the Academy was created, the Tuscan language was already hailed as a classic language. [7] Even though Tuscan itself originated from Latin, it gained tremendous recognition after the publication of Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy due to the entire poem being written in the Tuscan language. This famous and long poem tells the story of a man, Dante, and his journey through Inferno (Hell), Purgatorio (Purgatory), and Paradiso (Paradise). Through the journey, he meets various souls who teach him how to be a better person and what caused them to be where they are. This publication of his poem raised the Tuscan language into that of a vehicle of literary and official status. Soon after, other writers named Petrarch and Boccaccio published their work in the Tuscan language as well, causing further spread and love of the Tuscan tongue, [8] and these three authors became known as the "Tre Corone", or the 3 Crowns. [9]

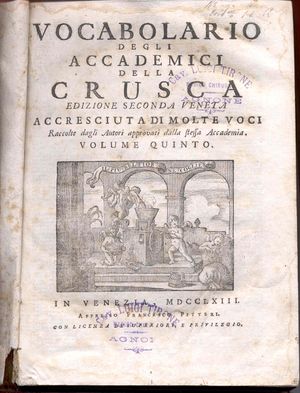

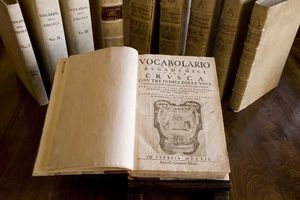

With the massive growth of admiration of the Tuscan language, the Academy set upon itself the duty to purify the Tuscan dialect and language and rid it of the vulgar words that filled the mouths of its speakers, as well as to improve the culture surrounding the Tuscan tongue. In order to do this, the Academy researched and compiled a list of both words that were commonly used and those deemed “acceptable” by the Academy, much of which came from the works of Petrarch and Dante, [10] but they also looked at modern writers (but still placing Florentine writers above all others) and at words with no ancient documented evidence. [11] Working with the model of a 14th century dictionary, which included canons and references to notable authors, the Academy attempted to showcase the continuity from ancient to modern Tuscan, with a preference for archaic authors and words because they believed that those were the purist form of the language. [12] They were able to maintain the integrity of their work and their goal by being completely self-financed by the founders, allowing for editorial freedom. [13] After years of writing and researching, the Academy published the first edition to their official dictionary, Vocabolario degli Accademici della Crusca, in 1612 in Venice.

The dictionary was a resounding success, despite conjuring up criticism for the words chosen in the dictionary. According to critics, the words were too archaic, and did not fully represent the beauty of the Tuscan language, which is used for asking for favours and returning thanks for them, excusing deficiencies, evading points, and for making love, [14] as well as the extremes on both ends of the spectrums of love, hate, politics, passions, and jealousies. [15] The critics failed to see that the words chosen were among those of which the common language which united Italy came about. [16] One point the critics made that was evident but not fixed until much later, would be the exclusion of general, every day and technical terms. [17]

The success of the first edition allowed the Academy to continue their research and compilation of words, so much so that the second edition was released in 1623 again in Venice and was edited by Bastiano de' Rossi. The second edition included more references to more authors and their works, however there were no major changes to the actual content. [18] The third edition, published in 1691, varied significantly from its two predecessors: for one, the third edition was a 3-volume set, instead of just a single volume; also the content, where an equal number of modern and ancient authors were analysed, [19] and included technical and scientific terms that were ignored in the first two editions; [20] as well as new abbreviations included, such as V.A which meant to indicate a word that was too archaic and therefore, unadvisable. [21]. Another significant aspect of the third edition is that it was the first to be published outside of Venice; this edition was published in Florence. Furthermore, it also included works of science, the arts and crafts, as well as abstract words. [22]

Then came the fourth edition, which is the largest one of those published, was released between 1729-1738 and it can be seen why the process took the longest. With the edition being a total of 6 volumes, the list of words deemed acceptable grew significantly over the course of a few decades since the third edition. However, this caused more stir of criticisms to the point where the edition was eventually abridged in 1739. [23] Shortly after the publication of the fourth edition, the Academy licensed two private reprints of the dictionary in Venice and in Naples.

These reprints differed as well from the original Academy’s work in terms of size (the Venice reprint is larger in size and the Naples is smaller) and in format, but they both remained in 6 volumes. They were also watched over carefully by the Academy, which received criticism for “ratifying archaic words and expressions to the detriment or the living language”. [24]This led to the Academy to be joined with three other Florentine academies (the Crusca, the Academia Fiorentina, and the Accademia degli Apatisti) in 1783 and became known as the Accademia Fiorentina. [25] The length of this edition coincided with the rise in the study of the everyday language in the 18th century, of which dictionaries began to include what became known as “language with no authority” into their content. [26]

The fifth, and final, edition was printed in 1863 after the Academy reopened as an independent institution in 1811 and continued their goals of revising the Vocabolario and preserving the Tuscan language. [27] Working with various new academics, the Academy included a vast new number of authors, especially in the arts and sciences, as well as split themselves into 4 different groups in order to complete the Vocabolario in a timely manner: one for Greek and Latin terms; scientific terms; examination and correction of grammatical theories; and revision of linguistic analysis [28]. Through this expansion, they included a glossary list which contained words that they deemed were foreign, corrupted, or even that they were uncertain of. [29] The first volume of the fifth edition was printed; however the subsequent volumes appeared sporadically until 1923, with the final volume not being completed.

Today, the Vocabolario is no longer being produced or researched, but the Academy is still in existence, having changed their focus to the study and promotion of the Italian language, as well as its historic knowledge. [30] They continue to analyze Italian grammar, lexicography, and philology, while maintaining contact with institutions abroad whose goal is to preserve the Italian language. The Academy is the world’s center for the scientific research into the language and offers countless Tuscan objects and services, such as a linguist advice service, for those interested in the Tuscan language. [31] Finally, they allow for public access to their Library and archive for those wondering about their history and findings since the 1570's.

- ↑ Encyclopedia Britannica: Crusca Academy http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/144822/Crusca-Academy#ref134653

- ↑ Accademia della Crusca http://www.accademiadellacrusca.it/en/accademia/history/origins-and-foundation

- ↑ Carmichael, Montgomery. In Tuscany: Tuscan Towns, Tuscan Types and The Tuscan Tongue. London: John Murray, 1901: 99.

- ↑ Coluzzi, Paolo.” Endangered Minority and Regional Languages (‘dialects’) in Italy.” Modern Italy, 14:1 (2009): 46.

- ↑ Ibid., 49.

- ↑ ouLearn on YouTube. “The Age of the Dictionary – The History of English (7/10).” Online video clip. YouTube. YouTube, 24 June 2011.

- ↑ Carmichael, Montgomery. In Tuscany: Tuscan Towns, Tuscan Types and The Tuscan Tongue. London: John Murray, 1901: 98.

- ↑ Ibid., 98.

- ↑ Beltrami and Fornara, "Italian Historical Dictionaries", 358.

- ↑ Encyclopedia Britannica: Crusca Academy

- ↑ Accademia della Crusca

- ↑ Beltrami and Fornara, "Italian Historical Dictionaries," 359.

- ↑ Ibid., 360.

- ↑ Carmichael, "In Tuscany," 105.

- ↑ Ibid., 16.

- ↑ Accademia della Crusca

- ↑ Beltrami and Simone, "Italian Historical Dictionaries," 363.

- ↑ Accademia della Crusca http://www.accademiadellacrusca.it/en/accademia/history/second-edition-vocabolario-1623

- ↑ Ibid., http://www.accademiadellacrusca.it/en/accademia/history/third-edition-vocabolario-1691

- ↑ Beltrami and Fornara, "Italian Historical Dictionaries," 362.

- ↑ Ibid., 362.

- ↑ Accademia della Crusca http://www.accademiadellacrusca.it/en/accademia/history/third-edition-vocabolario-1691

- ↑ Accademia della Crusca http://www.accademiadellacrusca.it/en/accademia/history/fourth-edition-vocabolario-1729-1738-and-suppression-accademia-1783

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Beltrami and Fornara, "Italian Historical Dictionaries," 364.

- ↑ http://www.accademiadellacrusca.it/en/accademia/history/reopening-accademia-1811-and-fifth-edition-vocabolario-1863-1923

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Accademia della Crusca http://www.accademiadellacrusca.it/en/accademia/history/accademia-today

- ↑ Ibid.