User:CarolineFaber

Altered Tales: Fairy Tales through Oral, Literary and Cinematographic Traditions

Fairy tales have existed for many thousands of years, playing an important role in cultures around the world and across time in a variety of forms. The current cultural needs, demands and ideologies, coupled with available technology of the time have worked together as an important force in altering fairy tales over time. Fairy tales have been available to audiences in oral, literary, and cinematographic forms, differing in form and message in accordance with the technology that dictates their existence. A second important factor in the altering of fairy tales over time has been the demands of both the home and receiving cultures as crucial variation changes occur as the fairy tales are passed on to new cultures and areas. A third factor in the alteration of fairy tales has been the changing societal movements, such as the acceptance of children as developing human beings as opposed to small adults.

| Together these changes have afforded an enormous amount of change upon fairy tales from thousands of years ago until today. This essay outlines briefly the movement of fairy tales from the realm of exclusive orality, to a division into two separate forms of fairy tales in literacy, and then further division to include the world of cinema. Each change in technology has brought with it new versions and adaptations of the fairy tales together with new audiences which further affect changes depending on audience demands and pressures. How have these changes shaped not only the stories themselves, but audiences and the messages found within? This Wiki attempts to address these issues, demonstrating the interesting changes that have been brought about in the magical world of fairytales since their first appearance to their many modern adaptations.

IntroductionFairytales have become a regular part of modern culture. Cinderella, Little Red Riding Hood and Hansel and Gretel evoke images in our minds so vivid we can literally see the scene of the story through our mind’s eye. But what is a fairy tale? Historians who study fairy tales have a myriad of points of view regarding the subject of fairy tales, including a wide range of definitions for what constitutes a fairy tale. Despite the wide array of definitions there does appear to be some consensus regarding the basic definition of the fairy tale.

|

Hans Christian Anderson Fairy Tales Hans Christian Anderson Fairy Tales

|

Orality and Fairy tales

While many may equate fairytales with the world of Disney and its mass produced capitalist exploitation of simple fantastical stories, fairytales have existed long before cinema began to dictate their existence. Fairytales actually existed in oral form long before either print or screen. Fairytales were stories which lay beneath the fabric of society and were transmitted between and amongst cultures as a means to achieving cultural continuity, to pass on information, and to provide entertainment.

Folklore historians suggest that the tales may have spread between and amongst societies in a myriad of ways, including by “women compelled to marry into alien tribes; by slaves from Africa to America; by soldiers returning from the Crusades; by pilgrims returning from the Holy Land or from Mecca; by knights gathering at tournaments; by sailors and travelers; and by commercial exchange between southern Europe and the East--Venice trading with Egypt and Spain with Syria.” (Gray, 2009) Once received by a new culture in a new geographical location, or by a different sector of society, fairytales were then adapted by the receiving cultures to create cultural relevance.

The Wolf and the Seven Kids The Wolf and the Seven Kids

|

Cultural anthropologist, Dr Tehrani, offers a brief glimpse into the history of Little Red Riding Hood, suggesting the tale goes back, according to historical traces, more than 2 600 years. Tehrani has found evidence of Little Red Riding Hood in more than 35 locations around the world, with more than 70 possible variations in plots and character development. The original tales is thought to be “The Wolf and the Kids” in which a wolf dresses in female costume, assuming the role of a nanny goat as he attempts to enter a house full of young goats. As the tale passed through cultures, it was adapted in terms of plots, character and message to reflect the new cultural biases. (Gray, 2009)

|

The Grimm brothers, on discussing the historical legacy of fairy tales, argued the lengthy and diverse history of fairy tales in that “the origin is in the fancy of a primitive people, the survival is through Marchen of peasantry, and the transfiguration into epics is by literary artists. Therefore, one and the same tale may be the source of Perrault's Sleeping Beauty, also of a Greek myth, and also of an old tale of illiterate peasantry.” (Kready, 1916) Fairy tales have altered over time, and retained a large degree of flexibility in their oral form with changes occurring in accordance with the society as a whole or smaller societal group of the times:

"For the roots of stories, we must look, not in the clouds but upon the earth, not in the various aspects of nature but in the daily occurrences and surroundings, in the current opinions and ideas of savage life." (Kready, 1916)

Fairy Tale: Hind in the Wood Fairy Tale: Hind in the Wood

|

While Tehrani agrees that tales may have been transmitted from culture to culture via “trade routes or with the movement of people,” (Gray, 2009) the purpose of oral fairy tales is in constant debate. Historian of fairy tales and their origins, Professor Jack Zipes, believes fairy tales may have been passed on from generation to generation as a vehicle for transmitting survival tips. (Gray, 2009) It was through fairy tales that cultures often found the means to disseminate information regarding daily survival and ways of life.

"A work of great interest might be compiled from the origin of popular fiction and the transmission of similar tales from age to age and from country to country. The mythology of one period would then appear to pass into the romance of the next century, and that into the nursery tales of subsequent ages. Such an investigation would show that these fictions, however wild and childish, possess such charms for the populace as to enable them to penetrate into countries unconnected by manners and language, and having no apparent intercourse to afford the means of transmission." (Keightly, 1834) Oral transmission was indeed sufficient in allowing the diffusion of fairy tales between and amongst cultures while allowing the necessary flexibility for cultural adaptations to shape the stories and make them culturally viable. The necessity for orality, in the absence of print, afforded a great deal of importance on the oral transmission the tales. |

Literacy and Fairy tales

Literary roots in fairy tales can be traced back to Ancient Egypt in 4000 BC where tales of magicians were recorded on papyrus. (Kready, 1916) The fairy tale, as an oral tradition, arose out of folktale and then further transformed through the literary tradition into the fairy tale. Written fairy tales, such as the Tale of Two Brothers (Egypt, 1300 BC), Cupid and Psyche (Roman, 100-200 AD) and Panchatentra (India, 200-300AD), arguably bear little resemblance to their original oral versions, having been changed for literary affect. (Wikipedia: Fairy tales) Fairy tales, transmitted originally through oral forms such as dramatic enactment and handed down through generations and across cultural lines, altered over time as a direct result of literary traditions and influences.

Teaching oral tales becomes difficult in the absence of print versions in which the alterations and origins of fairy tales is more evident. Evidence of literary versions of fairy tales can be traced back to more than 6000 years ago (Kready, 1916), and it is this movement to print that has actually enabled further exploration of the era of orality and the introduction of print. Ironically, it is the absence of print which provides evidence for the oral tradition of transmission of tales as folklore historians explore similarities and differences amongst the literary based versions as a means of arriving at rationalizations regarding the origin and history of various tales.

While the first movement towards literary in fairy tales occurred between 6000 and 500 years ago, this original print in fairy tales served only as a distant precursor to the literary versions which began to circulate 500 years ago and onwards. The tales were originally recorded as epics intended to be passed along through the new literary traditions. (Kready, 1916) During this period, fairy tales experienced a divide in product as oral traditions of transmission remained strong, in accordance with the needs of a largely illiterate society, and literary traditions utilized the forms of print to create modified versions of the tales which exemplified and experimented with the new possibilities of text.

The shift towards fairy tales as more akin to modern tales can be traced back to nearly 500 years ago. Writers around the world began to record fairy tales, as insets to other tales or as basic collections. Giovanni Straparola wrote The Facetious Nights of Straparola (Italy 1550 and 1553), containing excerpts of fairy tales in its many stories. Giambattista Basile wrote a collection fairy tales named the Neopolitan (Naples, 1634-6) and Pu Songling wrote Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio (China, 1761), showcasing various Chinese fairy tales of the time. (Wikipedia: Fairy tales) It is also during this era that the Contes of Jean de La Fontaine and Charles Perrault fixed the forms of such modern tales as Sleeping Beauty and Cinderella.

| A shift in literary recording of fairy tales occurred in the eighteenth century when collectors attempted to preserve, not only the plot and characters of fairy tales, as their literary predecessors had done, but also the oral style in which they were preserved. (Lamers) The German Brothers Grimm worked to collect fairy tales that were German and oral in origin, rejecting tales that were of other cultural origins and had been adapted for literary interests. Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm collected stories that reflected “life as generations of central Europeans knew it—capricious and often cruel.” (National Geographic, 1999) Their goal, to preserve the Germanic folktales, dictated which stories were accepted in their collections and which were rejected. Many tales of Perraault, such as Bluebeard, were rejected due to their French roots while others, such as Briar Rose, clearly related to Perraults’ Sleeping Beauty, were allowed to remain part of the collection due to intrinsic features of the text suggesting German roots. (Wikipedia: Fairy tales)

“Once they saw how the tales bewitched young readers, the Grimm brothers, and editors aplenty after them, started "fixing" things. Tales gradually got softer, sweeter, and primly moral. Yet all the polishing never rubbed away the solid heart of the stories, now read and loved in more than 160 languages.” (National Geographic, 1999) The Brothers Grimm affected a great number of changes to the nature of the tales themselves, changes which can be seen to have affected the evolution of fairy tales from this point onward. |

Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm

|

Many factors contributed to the alteration of the tales. First, the recognition of childhood as a unique stage of development opened the doors for making the fairy tales more acceptable for reading with children. (Lamers) Children’s literature as a genre did not appear until the mid-seventeenth century, until that time children were viewed as being miniature adults, and thus a separate genre of literature geared towards their needs was not inline with cultural ideas of the day. (Wikipedia: Children's Literature) The Grimm brothers worked to reduce the number of sexual references, evidenced in Rapunzel, whereby, “in the first edition, revealed the prince's visits by asking why her clothing had grown tight, thus letting the witch deduce that she was pregnant, but in subsequent editions carelessly revealed that it was easier to pull up the prince than the witch.[60]” (Wikipedia: Fairy tales)

Conversely, for a period of time, the importance of justice for the strong archetypal characters increased in terms of violence, particularly when punishing villains.

A final important influence on literary fairy tales came as a result of the morally weighted pressures of the Victorian age. Fairy tales were often employed as a means to teaching important life lessons to children and often providing frightening lessons so they would listen to their parents and behave. (Lamers) Victorian fantasist, G.K. Chesterton, remarks in his 1908 essay that:

"If you really read the fairy tales, you will observe that one idea runs from one end of them to the other — the idea that peace and happiness can only exist on some condition. This idea, which is the core of ethics, is the core of nursery-tales…. A promise is broken to a cat, and the whole world goes wrong. . . This is the profound morality of fairy-tales; which, so far from being lawless, go to the root of all law. Instead of finding (like common books of ethics) a rationalistic basis for each Commandment, they find the great mystical basis for all Commandments." (Spitalny)

Writers such as Hans Christian Anderson, the Brothers Grimm, and many others incorporated the heavily weighted Victorian moral ideals into their tales. Fairy tales became less sexualized and violent, increasingly archetypal, heavily morally weighted, and increasingly geared towards a primary young audience. (Lamers) The modern fairy tale of the time became a tale in which the reader would be exposed to lessons of appropriate behaviour, etiquette, and values of the Victorian society. Vigen Gurgoian argues that the new literary fairy tales were so widely accepted because they “attractively depict character and virtue. In these stories the virtues glimmer as if in a looking glass, and wickedness and deception are unmasked of their pretensions to goodness and truth. These stories make us face the unvarnished truth about ourselves while compelling us to consider what kind of people we want to be.” [http//:www.catholiceducation.org/articles/arts/al0134.html Gurgoian, 1996])

From this perspective and the advent of cinema, fairy tales moved to a realm which centered primarily on the entertainment and morality of children.

Cinematography and Fairy Tales

Cinema has had an undeniable effect on the transmission of fairy tales in society, allowing for a return to dramatization while animation and special effects have created a new arena of increased plausibility. One of the original cinematographic fairy tales, 1930’s German silent film of The Wolf and the Seven Little Kids, a tale thought to be the origin of Little Red Riding Hood, (Wikipedia: Fairy tales)utilizes rudimentary pixilation techniques to animate the characters while creating a static playground for the characters who are captured on film. While many fairy tales have been captured on film by various companies and producers, Disney has captured much of the film industry’s attention in the arena of fairy tales, beginning with their 1939 release of Snow White. (Wikipedia: Fairy tales)

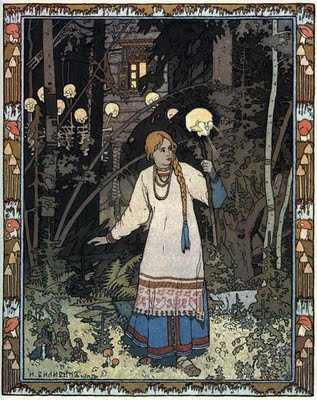

Vasilisa the Beautiful Vasilisa the Beautiful

|

While this film was originally intended for both children and adults alike, the simple tidy plot lines and happy perfect endings may have encouraged a predominantly youth audience which was later replicated in the newer versions of Disney fairy tale films. Scholars, such as Zipes, Tatar, and Filine argue that Disney has stripped the fairy tale of its moral messages and meaning, rendering the fairy tales devoid of meaning and applicability to modern culture in any way other than for entertainment value. Zipes notes that Disney’s film version of Snow White was a “story that [Walt Disney] had taken from the Grimm Brothers and changed completely to suit his tastes and beliefs. He cast a spell over this German tale and transformed it into something peculiarly American." (Jones, 2007) Bethany Jones reminds readers of the general stability of fairy tales in that from the time of “Perrault to the Brothers Grimm, much retelling is similar, with only slight variances…[while] Disney, however…alters the story not only by point of view, but also in its moral and its core message.” (Jones, 2007)

"Walt Disney's Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs has so eclipsed other versions of the story that it is easy to forget that hundreds of variants have been collected over the past century in Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Americas" (Jones, 2007) |

| While Disney has had a profound affect on the appearance of fairytales in cinema and the view of fairy tales as in the domain of children, other countries also aided in the purporting this outlook through the release of their own fairy tale full length feature films which were geared towards young audiences. In 1939, Russian Aleksandr Rou made the fairy tale Vasilisa the Beautiful into a full-length, large budget feature film in the Soviet Union, the first of its kind favouring a fantastical approach in place of the politically accepted realistic elements of style.” (Wikipedia: Fairy tales)

|

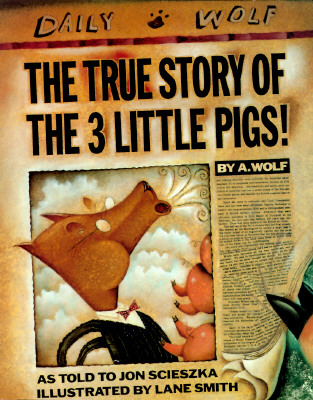

The True Story of the Three Little Pigs, by Jon Scieszka The True Story of the Three Little Pigs, by Jon Scieszka

|

Conclusion

Fairy Tales continue to evolve, whether in oral, literary, or cinematographic form. Their evolution comes as a result of changing societal demands, ideals, and notions on human behaviour and expectations. From the time of orality, fairy tales have been transmitted from one culture to another, from one era to the next, altering, reconfiguring, and adjusting to both reflect and support the culture in which they are found.

Fairy tales have progressed from being solely teaching tools and stories passed on through dialogue, to literary and cinematographic reflections of our culture. Each new change does not erase the former version, and a reintroduction of form can carry with it critical effects, such as the reintroduction of literary form in the eighteenth century and modern satirical fairy tale versions.

Fairy tales are constantly altering and adjusting in light of both societal and technological pressures. Current cultural expectations, along with the pressures of current technology create alterations in fairy tales in terms of form, message, content and context. Fairy tales continue to alter in content, often as a reaction to technological changes imposed upon them. Reflections of cultural needs and demands, fairy tales will continue to alter and respond to the ever changing expectations of our society. Perhaps the only constancy to be found in fairy tales is their ability to consistently evolve to meet the needs of the current society.

References

Chesterton, G. The ethics of fairy tales. Accessed at: http://www.readbookonline.net/readOnLine/20593/

Guroian, V. Awakening the moral imagination: Teaching virtues through fairy tales. The Intercollegiate Review (Fall, 1996). Retrieved at: http//:www.catholiceducation.org/articles/arts/al0134.html

Gray, R. (2009) Fairy tales have ancient origin: Popular fairy tales and folk stories are more ancient than was previously thought, according research by biologists. Retrieved from: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/science/science-news/6142964/Fairy-tales-have-ancient-origin.html

Heiner, H. (1999) Sur la lune fairy tales: The history of Beauty and the Beast. Retrieved at: www.surlalunefairytales.com

The History of Fairy Tales (n.d.) http://individual.utoronto.ca/h_forsythe/02_redandcindy.html

Jones, B. (2007) How Disney damages fairy tales and folklore. Retrieved at: http://www.associatedcontent.com/article/417740/how_disney_damages_fairy_tales_and_pg4_pg4.html?cat=23

Keightly, T. (1834) Tales and popular fictions: Their resemblance and trasnmission from country to country. Whitaker and Co., London. Retrieved at: http://books.google.ca/books?id=6oi81BwNMDwC&pg=PA9&lpg=PA9&dq=A+work+of+great+interest+might+be+compiled+from+the+origin+of+popular+fiction+and+the+transmission+of+similar+tales+from+age+to+age+and+from+country+to+country.+The+mythology+of+one+period+would+then+appear+to+pass+into+the+romance+of+the+next+century,+and+that+into+the+nursery+tales+of+subsequent+ages.+Such+an+investigation+would+show+that+these+fictions,+however+wild+and+childish,+possess+such+charms+for+the+populace+as+to+enable+them+to+penetrate+into+countries+unconnected+by+manners+and+language,+and+having+no+apparent+intercourse+to+afford+the+means+of+transmission&source=bl&ots=cBAYl70xkv&sig=GzZgfrNlfBCJyZST80CDlxk0w3I&hl=en&ei=eL_4SviJApK0sgP_kajGCQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CAgQ6AEwAA#

Kready, L. (1916) A study of fairy tales. Retrieved at: http://www.sacred-texts.com/etc/sft/sft07.htm

Lamers, E. Literature for children. (n.d.) Retrieved at:

http://www.deathreference.com/Ke-Ma/Literature-for-Children.html

National Geographic. (1999) Grimm’s Fairy Tales. Retrieved at: http://www.nationalgeographic.com/grimm/index2.html

Ng, A. (2006) Fairy Tales: The real deal behind their morals and character

stereotypes. Retrieved at: http://www.associatedcontent.com/article/76676/fairy_tales_the_real_deal_behind_their.html?cat=38

Spitalny, S. The path of a frog king. Acessed at: http://www.waldorflibrary.org/Journal_Articles/frogking.pdf

Wikipedia: Children’s Literature. (n.d.) Retrieved at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Children's_literature

Wikipedia: Fairy Tales. (n.d.) Accessed at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fairy_tale