Low Income Among Immigrants in Canada

Measurements of low income in Canada

Canada uses three types of indicator to define low income: Low-Income cut offs, Market Basket Measure and Low-income measure. The Low Income cut offs considers a family low income when it spends 20% more on basic necessities compared to the average family. Meanwhile, the Market Basket measure takes into account whether the individual has enough to purchase services and goods that represent the basic standard of living. The Low Income Measure compares the income to a fixed percentage. If it falls below 50% of the median household, it would be considered low income[1].

Trend among immigrants

The low income rates among immigrants in Canada throughout the past decades had varied depending on the economic conditions, but it continues to be relatively high[2]. Among recent immigrants, the rate increased from 25% to 36% from 1980s to 2000s. Among the immigrants who have resided in Canada for 11 to 15 years, the numbers rose from 15% to 23% between 1980 to 2000 and slightly declined by 2010[3].

In regards to low-income rates relative to Canadian-born, the numbers have steadily risen among immigrants. In the 1980s the rate of low income among recent immigrant was 1.4 times higher in comparison to Canadian- born. This number has increased to 2.7 times. Unemployment leading to poverty is also higher by 3% among immigrants[4].

Among immigrants in low income, 51% are in chronic low income which is higher in comparison to the numbers of Canadian-born in chronic low income. This pattern is seen in both long tenured and recent immigrants[5]. Although the absolute rate of chronic low income has fallen over the years, its relative rates have increased.

Education

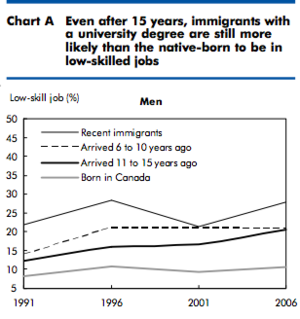

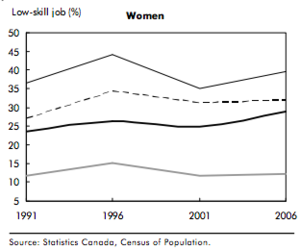

In recent years, immigration policies have changed, becoming more selective, allowing entry to those who meet the skill and educational credentials. This has created a population of recent immigrants that are highly skilled and educated. Approximately one-half of the working-age immigrants have a university-level qualification. Since the 1990s, the growth in the number of immigrants with at least a bachelor’s degree was comparable to the rise in the level of education among native-born Canadian. Despite the increase in educational attainment, earning gap between immigrants and Canadian born persist in today’s society. University degree and work experience from outside of North America tend to be undervalued, placing these people at a disadvantage in the job market. The effect is evident in the difference in employment opportunity and income. Immigrants who possess a university degree, earn a slightly lower median earnings in contrast to domestic-born educated individuals. The impact is also more prominent in Canada in comparison to the U.S. Immigrants in Canada are more likely to equally as high educated, while in U.S, they are less educated than the native-born Americans[6]. Over the past years,the earning gap between the two groups in Canada has widened, with immigrants falling further behind[7].

The likelihood of falling into chronic low-income is not significantly affected by the level of education. According to data in 2012, those with a postsecondary education were only 1.1 times lower than those who possess a secondary school degree[8]. Although educational attainment among recent immigrants has over time, largely increased, the challenges of finding a high-income occupation that reflects their level of knowledge and skills.

Employment opportunity

Today’s immigrants are, on average more likely to have appropriate knowledge of an official language and be graduates from a high in demand fields such as applied science, computer science, and health sciences. However, a large proportion is over-represented in jobs that require low educational requirements[9]. These people often find and remain in work known as “survival jobs” with minimum wage, no benefits, and work stability. These include jobs such as security guards, gas station helpers, cashiers and customer service [10]. In the past twenty years, the count of skilled and highly educated immigrants in these low-income jobs have been steadily rising from 26% to 28%. Within this group, South Asian and Southeast Asian males are the largest groups representing 38% and 42%[11]. In contrast to native-born Canadians who also have a specialized degree, immigrants representation in low educational occupations is relatively higher, while recent immigrants are even higher[12].

As foreign training are generally not recognized in Canada, professional individuals from abroad have to build up their career from the bottom, placing them at the initial level with lower pay.This issue is also more predominant among East Asian countries such as China and India. Their skills are less accepted and work experiences from their home country are less transferable when compared with individuals moving from the U.S, Britain or France with similar qualifications[13].

The hardship with integration into the job market and finding occupation relevant to their knowledge and ability impedes many immigrants from catching up to canadian-born workers in terms of work stability and earnings.

Among those who manage to acquire a position in their field of study are paid less than their native-born counterpart and are more likely to struggle with mobility from technical skills work to management jobs[14].

Gender difference

Participation in the labour force among immigrant women and men vary to a great extent, leading to differences in income. Women are more likely to take longer to integrate into the labour force than men[15]. They have to take into account various responsibilities such as family care and settlement issues. Education -to-job mismatch is also more common among immigrant women. A majority of them work in positions that do not require a post-secondary degree when many possess higher education credentials[16]. The mismatch between skills and occupation is less prominent in men with 41% of males reporting this discrepancy while 48% to 60% of female experience this incongruence[17]. The income of low-income rate is moderately higher than male by 1.3 times. This is likely the result of the type of work. In comparison to men, women, especially, recent immigrants tend to settle for part-time work as opposed to full time. Women who work full time or part time are generally wage earners, very few are self-employed. A small number of approximately 9.2% of them work in self-employment, in contrast to 16% of immigrant men. Many women gravitate towards traditional gendered occupations, such as sales and administrative field[18]. This pattern is also seen among Canadian-born women. However, those born in Canada are more likely to achieve managerial positions. A greater fraction of immigrants works in manufacturing and utilities[19].

Immigrant class differences

There are different types of immigrants: family class, refugees, and economic class. Those who are refugees and family class immigrants have a slightly higher chance of being low incomes. Individuals from economic class are often skilled workers with the better ability to enter and succeed in the labour market[20]. They also have qualifications and higher language proficiency allowing them to overperform the other two groups in the work sector[21]. A similar trend appears when comparing rates of chronic low income in which refugees and family class immigrant have marginally higher percentage of representation[22].

References

- ↑ Government of Canada. (2016). A Backgrounder on Poverty in Canada. Ottowa, ON: Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/poverty-reduction/backgrounder.html#h2.1

- ↑ Picot, G. & Hou, F. (2014). Immigration, Low Income and Income Inequality in Canada: What's New in the 2000s?. Social Analysis and Modelling Division, Statistics Canada, Ministry of Industry. Ottawa, ON. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/11f0019m/2014364/mi-rs-eng.htm

- ↑ Picot, G. & Lu, Y. (2017). Chronic low Income Among Immigrants in Canada and its Communities. Statistics Canada, Ministry of Industry. Ottawa, ON. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/11f0019m/11f0019m2017397-eng.htm

- ↑ Government of Canada. (2016). A Backgrounder on Poverty in Canada. Ottowa, ON: Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/poverty-reduction/backgrounder.html#h2.1

- ↑ Picot, G. & Lu, Y. (2017). Chronic low Income Among Immigrants in Canada and its Communities. Statistics Canada, Ministry of Industry. Ottawa, ON. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/11f0019m/11f0019m2017397-eng.htm

- ↑ Picot, G. & Hou, F. (2014). Immigration, Low Income and Income Inequality in Canada: What's New in the 2000s?. Social Analysis and Modelling Division, Statistics Canada, Ministry of Industry. Ottawa, ON. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/11f0019m/2014364/mi-rs-eng.htm

- ↑ Stanford, J. (2008). Work and labour in canada: Critical issues

- ↑ Picot, G. & Lu, Y. (2017). Chronic low Income Among Immigrants in Canada and its Communities. Statistics Canada, Ministry of Industry. Ottawa, ON. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/11f0019m/11f0019m2017397-eng.htm

- ↑ Galarneau, D. & Morissette, R. (2008). Immigrants’ Education and Required Job Skills. Statistics Canada. Ottowa, ON. https://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/75-001-x/2008112/pdf/10766-eng.pdf

- ↑ Blasio, S.D. (2014, April 30th). Working Poor? Immigrant survival jobs and poverty. Canadian Immigrant. http://canadianimmigrant.ca/living/community/working-poor-immigrant-survival-jobs-and-poverty

- ↑ Galarneau, D. & Morissette, R. (2008). Immigrants’ Education and Required Job Skills. Statistics Canada. Ottowa, ON. https://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/75-001-x/2008112/pdf/10766-eng.pdf

- ↑ Bonikowska, A., Hou, F. & Picot, G. (2011).Do Highly Educated Immigrants Perform Differently in the Canadian and U.S. Labour Markets?. Social Analysis Division. Statistics Canada. Ottowa, ON. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/11f0019m/11f0019m2011329-eng.pdf

- ↑ Stanford, J. (2008). Work and labour in canada: Critical issues

- ↑ Galarneau, D. & Morissette, R. (2008). Immigrants’ Education and Required Job Skills. Statistics Canada. Ottowa, ON. https://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/75-001-x/2008112/pdf/10766-eng.pdf

- ↑ Hudon, T. (2017). Immigrant women. tatistics Canada, Ministry of Industry. Ottawa, ON. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-503-x/2015001/article/14217-eng.htm#a23

- ↑ Galarneau, D. & Morissette, R. (2008). Immigrants’ Education and Required Job Skills. Statistics Canada. Ottowa, ON. https://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/75-001-x/2008112/pdf/10766-eng.pdf

- ↑ Hudon, T. (2017). Immigrant women. tatistics Canada, Ministry of Industry. Ottawa, ON. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-503-x/2015001/article/14217-eng.htm#a23

- ↑ Galarneau, D. & Morissette, R. (2008). Immigrants’ Education and Required Job Skills. Statistics Canada. Ottowa, ON. https://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/75-001-x/2008112/pdf/10766-eng.pdf

- ↑ Hudon, T. (2017). Immigrant women. tatistics Canada, Ministry of Industry. Ottawa, ON. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-503-x/2015001/article/14217-eng.htm#a23

- ↑ Picot, G. & Lu, Y. (2017). Chronic low Income Among Immigrants in Canada and its Communities. Statistics Canada, Ministry of Industry. Ottawa, ON. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/11f0019m/11f0019m2017397-eng.htm

- ↑ Hou, F., and G. Picot. 2016. Changing Immigrant Characteristics and Entry Earnings. Analysis Branch Research Paper Series, no. 374. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 11F0019M. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

- ↑ Picot, G. & Lu, Y. (2017). Chronic low Income Among Immigrants in Canada and its Communities. Statistics Canada.