Housing Discrimination and Connections to Racialized Spaces

Introduction

Though much progress has been made to achieve greater equality between individuals of all backgrounds, discrimination is still ever present in housing markets. This discrimination can be based on one’s gender, race or ethnicity. Discrimination practiced in housing markets by real estate agents and rental property owners preserve patterns of housing and neighbourhood inequality that severely disadvantages minority groups (Margery et al., 2012 xi).

Definitions

Housing Discrimination occurs when an individual is discriminated against and treated unfairly on the basis of their characteristics such as class, race, gender, ethnicity or sexual orientation when it comes to buying a house, renting or leasing. Closely associated to housing discrimination is the racialization of space. Maya Wiley, founder and director of The Center for Social Inclusion provides a great definition of the racialization of space: it is a process where neighbourhoods or residential areas become identified or associated with the race of its inhabitants; the racialization of spaces entails the building of political power and to do this, “racially identifiable districts” must be established (Shiffman, 2012, p. 21). To get a better understanding of this concept, Wiley gives an easy example from the United States. When you say that someone is from the ‘hood’ everyone would assume that that you are talking about African Americans, by referring to an area as the ‘hood,’ one has racialized a space (p. 21).

Trends in Housing Discrimination

In their study of the persistence of housing market discrimination against African American and Hispanic home seekers, Ross and Turner (2005) found that “discrimination against Hispanics in access to rental housing, racial steering of African Americans, and less assistance to Hispanics in obtaining financial aid” still exists (p. 152). Racial steering is the process whereby realtors steer homebuyers towards or away from specific neighbourhoods based on their race. Studies reveal that bias is present across multiple dimensions, with blacks and Hispanics experiencing “consistent adverse treatment in their housing searches” than white people (Pager and Shepherd, 2008, p. 188). Measured discrimination took the form of less information offered about housing units, fewer opportunities to view houses, less assistance with financing and steering into less healthy communities and neighbourhoods (p. 188). An implication of these findings is that differential treatment creates barriers for minority groups. With such barriers, these groups have a much more difficult time in obtaining quality housing. Facing limited options, they are pushed into areas that are undesirable.

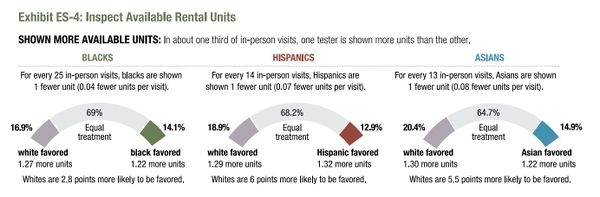

The figures on the right show that whites are significantly more likely to be favoured than minorities. Black, Hispanic, and Asian renters are all shown significantly fewer housing units than equally qualified whites. Photo is courtesy of The United States Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Effects of Housing Discrimination

Housing Discrimination can have immense negative effects on the livelihood of families and their children. Having access to quality housing and neighbourhoods is a “crucial factor in shaping the social and economic outcomes of American families and children,” but when one adds discrimination to the equation, favourable outcomes automatically decrease significantly (Ross and Turner, 2005, p. 152). Discrimination greatly undermines the life chances of minorities by reducing their access to socioeconomic opportunities and introducing mental stress to daily life (Yang, Chen, & Park, 2016, p. 789). Racial discrimination in housing markets essentially acts as a sorting process that leads minorities to reside in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighbourhoods with high poverty rates. Substandard housing conditions have been found in association with the presence of cockroaches, rats, water leaks, poor ventilation, and exposure to harmful chemicals (p. 790). This means higher rates of diseases and worse health for families. In addition, residing in low quality residential areas means that there is less access to facilities and services such as community and recreation centres, good schools, grocery stores, etc; all these amenities are important in an individual’s well-being. What is important to know about housing is that it plays a crucial role in “linking an individual or a family to the society…” (p. 790). Without fair housing opportunities, minority groups are pushed to the margins of society, isolated from the dominant groups that wish to keep them there. Furthermore, Yang et al. (2016) suggest housing discrimination can have negative consequences on an individual’s self-esteem or self-perception (p. 790). Decent housing in a stable neighbourhood provides one a sense of belonging and safety; social capital is established when people interact with each other (from simple greetings or just talking to each other about how their day went). However, the opposite occurs in those residing in underserved areas. Without the facilities, services, and schools that help people come together to interact and connect, those in underserved areas may feel alienated. Some may even feel inferior and embarrassed to live in inadequate areas.

Why Does Housing Discrimination Still Exist?

One of the possible reasons for this discrimination is simply prejudice (Ross and Turner, 2005, p. 153). In the housing market, a realtor may provide less service and information to a well-qualified minority homebuyer than to “an equivalent home homebuyer in order to avoid contact with the minority” (p. 153). Or, “the agent may provide minority homebuyers information on different housing units and neighbourhoods due to a prejudiced belief concerning where minorities should or should not reside” (p. 153). The holding of inaccurate stereotypes, expectations and assumptions concerning minority groups plays a huge role in discrimination; some individuals may act on them unconsciously without even realizing it. Though it can be tempting to view discrimination in terms of solely based on an individual's attitudes, prejudices and biases, it is also important to be to examine society as a whole; particularly, the structures and beliefs that make up society. Members of racial minority groups may be systemically disadvantaged not only by the willful acts of particular individuals, but because the prevailing system of opportunities and constraints favours the success of one group over another (Pager and Shepherd, 2008, p. 197). Broader structural features of society can contribute to unequal outcomes that minorities face through the ordinary functioning of its cultural, economic, and political systems (p. 197). These structures become embedded in the workings of society and when they become embedded, we often forget about their presence and act unconsciously on them. When discrimination becomes institutionalized, individuals in that society internalize them and come to see them as real and unchanging, thus contributing to systematic disadvantage of minorities. A point can also be made about history. African Americans have had a long history wherein they were viewed as inferior and deviant beings. The involvement of the American Federal Government and interest groups like the National Association of Real Estate Boards in promoting suburbanization prior to and following World War II is something to focus on. When African Americans migrated to urban areas, local and national relator associations disseminated an ideology that “associated the presence of Africana Americans in residential areas with moral decay, crime, and diminishing poverty values” (Shircliffe, 2004, p. 2).This ideology associating race with space became embedded in the development of the real estate industry and the policies of the federal housing administration; thus, the racialization of space promoted by real estate practices fuelled anti-black violence as white homeowners saw Africana American residents as threats to their livelihood and property values (p. 2). Fast forward to today, there is no doubt that improvements have been made since the passing of the Fair Housing Act in 1968, but more work needs to be done. History shapes societal structures and these structures (which includes attitudes, norms, beliefs) become ingrained. This is very difficult to change. When ideas become entrenched and stay for a very long time, people come to view them as something that is true and natural; they do not question it since it has always been there. Racism is no exception. Things may appear to have progressed greatly, but as Shircliffe quotes in her article, “the ways in which residential segregation is maintained are part of the new racism in which racialized meanings are embedded in seeming non-racial or race neutral categories” (p. 2). The structural mechanisms and ideologies that perpetuate segregation are indeed still intact and much work needs to be done to eliminate them.

The Link Between Race and Space

Characteristics of Space

Neely and Samura (2011) investigate how one can understand the connection between race and space. They identify four characteristics of space: it is contested, fluid and historical, relational and interactional, and characterized by difference and inequality (p. 1939). Space is not fixed, it changes, hence why they characterize it as fluid. The fluidity of space is a result of the relational and interactional processes that occur and sometimes, the social actors (i.e. individuals, groups, governments) involved in these interactions can “create, disrupt, and recreate spatial meaning through interaction with one another” (1939). With this in mind, Neely and Samura (2011) put forth the idea that spaces reinforce power structures (1940). Space can serve as a means for the creation and maintenance of social inequality and a manifestation of systemic racial inequalities. Think of residential segregation, and the land theft of Canada’s Aboriginal people’s. Looking at history, particularly, from the perspective of First Nations in Canada, they have had their land taken away from them and forced to moved onto reserves. Their sacred land has been turned to a space for economic purposes and the reserves on which they live are often neglected by the government. They have been displaced from the natural land that gives them their livelihood and forced to relocate into spaces that have low quality housing and lack facilities such as community centres. By forcing First Nations into these kinds of spaces, the government has reinforced the power structure. First Nations are marginalized and kept at the bottom of the hierarchy while the government pursues policies that are antithetical First Nations needs.

How Housing Discrimination Creates the Racialization of Space

When minorities are confined to spaces, the spaces they become confined to are racialized. The space that they are forcibly moved to come to be known as a space for African Americans, Hispanics, or Asians, in which some of the words used to describe these spaces are ‘hood’ or ‘ghetto.’ Lipsitz (2007) states that race acts as a key variable in determining who has the ability to own homes that appreciate in value; it “decides which children have access to education with experienced and credentialed teachers in safe buildings with adequate equipment, and it shapes differential exposure to polluted air, water, food, and land” (p. 12). Opportunities in society are both spatialized and racialized, so, what arises when spaces become racialized on the basis of discrimination is a cycle of inequality that is hard to break out of. If housing ownership is based on race, then minority groups considered inferior are at the bottom of the hierarchy and are kept in disadvantaged positions. Stuck in underserved and low quality homes and neighbourhoods, notions of superiority and inferiority are perpetuated where the idea being presented is that minorities are not working hard enough to move themselves out of this situation when in fact, it is discrimination that is preventing them from doing so.

An Intersectional Analysis

Though housing discrimination can happen on the basis of race, it may also happen on the basis of gender, class and sexual orientation. For example, Kattari, Whitfield, Walls, Magruder, & Ramos (2015) in their study find that members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) community experience higher rates of discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity than their heterosexual and cisgender counterparts (p. 441). Likewise, Ahmed and Hammarstedt's (2009) findings show that homosexual males are discriminated against in the Swedish housing market, since the homosexual couple gets far fewer call-backs and fewer invitations to showings of apartments than the heterosexual couple (p. 588). What these findings demonstrate is that race does not act alone in bringing people disadvantages. One’s sexual orientation, class, and gender can too. When one looks back at history, heteronormativity has long been held as the normal and correct way of acting; the belief that people fall into distinct categories of gender (male or female) and that heterosexuality is the norm was the widely held belief. This is perhaps why the nuclear family was considered as the ideal family type with a man and a woman getting married and having kids. Associated with the nuclear family is the expectation that the woman stays home and while the man is the breadwinner. Also, in the past women were seen as not being able to hold property. As times have changed, such thinking has mostly been stamped out but not completely. When an individual deviates from the norm, they can be seen as threats to the overall well-being of a neighbourhood and deliberately be kept out of these neighbourhoods by others due to the traditional beliefs that are still prevailing. For example, a homosexual couple may want to move into a predominantly heterosexual neighbourhood but may be prevented from doing so due to the belief that if a homosexual couple moves in, then they will taint the neighbourhood. For some, homosexuality threatens the nuclear family model while others do not want their children to be exposed to homosexual ideas. In addition, labels given to certain races and ethnicities play a role; too often white people are seen as intelligent, and hardworking, while blacks are seen as lazy, not hard working and delinquents. When they are ascribed these assumptions, they have less of an ability to move up the ladder as they constrained by these negative views that others have of them. Taken all together, race, gender, and sexual orientation can generate exclusivity that functions as a mechanism for skewing the opportunities and life chances for others. A lower class, homosexual woman from a minority group for example would have a harder time looking for adequate housing than a white, middle or upper class heterosexual woman. The current norms, beliefs, and attitudes about categories of people all have a hand in keeping her in the disadvantaged situation.

References

Ahmed, A. M., & Hammarstedt, M. (2009). Detecting discrimination against homosexuals: Evidence from a field experiment on the internet. Economica, 76(303), 588-597. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0335.2008.00692.x

Calmore, J. O. (1995). Racialized space and the culture of segregation: hewing a stone of hope from a mountain of despair. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 143(5), 1233-1273.

Kattari, S. K., Whitfield, D. L., Walls, N. E., Langenderfer, L., & Ramos, D. (2016). Policing gender through housing and employment discrimination: Comparison of discrimination experiences of transgender and cisgender LGBQ individuals. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 7(3), 427-447. doi: 10.1086/686920

Lipsitz, G. (2007). The racialization of space and the spatialization of race: Theorizing the hidden architecture of landscape. Landscape Journal, 26(1), 10-23. doi: 10.3368/lj.26.1.10

Margery, T., Santos, R., Levy, D., Wissoker D., Aranda, C., Pitingolo, R. (2012). Housing discrimination against racial and ethnic minorities 2012. Retrieved from U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Website: https://www.huduser.gov/portal/Publications/pdf/HUD-514_HDS2012.pdf

Neely, B., & Samura, M. (2011). Social geographies of race: Connecting race and space. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 34(11), 1933-1952. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2011.559262

Pager, D., & Shepherd, H. (2008). The sociology of discrimination: Racial discrimination in employment, housing, credit, and consumer markets. Annual Review of Sociology, 34(1), 181-209. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131740

Ross, S.L., & Turner, M. A. (2005). Housing discrimination in metropolitan America: Explaining changes between 1989 and 2000. Social Problems, 52(2), 152-180. doi: 10.1525/sp.2005.52.2.152

Shircliffe, B. (2004). Review of Gotham, Kevin Fox, race, real estate, and uneven development: The Kansas City experience. H-Education, 1900-2000.

Shiffman, R. (2012). Racialized public space: an interview with Maya Wiley. Race, Poverty, and the Environment, 19(2), 21-23.

Yang, T., Chen, D., & Park, K. (2016). Perceived housing discrimination and self-reported health: How do neighborhood features matter? Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 50(6), 789-801. doi: 10.1007/s12160-016-9802-z