Herbivore Masculinity

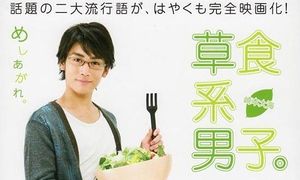

Herbivore masculinity, a term coined by Maki Fukasawa in 2006, gained prominence in 2009, as Japan saw a rise in the numbers of herbivore men (66).[2] The term comes from the Japanese translation for sex, which means “relationship in the flesh" (89).[3] As herbivore men are described as disinterested in sexual intimacy, the term presents this accordingly (89).[3] Furthermore, this term reflects the idea that herbivores are lower on the food chain and more placid and non-assertive, just as herbivore men are (70).[2]

The rising popularity of herbivore masculinity countered the hegemonic salaryman masculinity that had been dominant in Japan since post-World War II (89).[3] It is important to note that both salaryman and herbivore masculinities have been based on a heteronormative model, meaning that both of these masculinities are focused on a relationship between men and women (99).[3] Although herbivore masculinity has long existed in Japan, as a result of a shifting social and economic landscape, herbivore masculinity has gained prominence in Japan, shocking and challenging Japan's society (66).[2]

Origins

Herbivore masculinity became more prevalent after the hegemonic salaryman masculinity emerged. Therefore, to understand how herbivore masculinity came to be, the origins of salaryman masculinity must be explored.

Post-World War II in Japan, the hegemonic salaryman masculinity and the complementary, subordinate housewife femininity, became more popular and widespread (90).[3] In this post-World War II period, Japan experienced economic growth that really supported the salaryman masculinity and allowed it to prosper. It was in this period that Japan became the third largest economy in the world, after the United States and the Soviet Union.[4] As the economy boomed, Japan was able to attain pre-war production levels by 1955 and experienced record economic growth, of 10% per year, until the 1970s.[4] From the 1960s to the 1970s in particular, Japan experienced especially high economic growth (76).[2] Japan's bubble period, in the late 1980s, further supported salaryman masculinity, as the period allowed large companies to smoothly and securely provide lifetime employment to recently graduated students (76).[2]

As the salaryman masculinity became the hegemonic masculinity in Japan, the traits of salarymen became desired and respected traits for all Japanese men to acquire. These traits included absolute loyalty, diligence, dedication and self-sacrifice to their companies (91).[3] Salarymen also became notoriously known in Japan for their workaholicism, inability to express emotions and their excessive alcohol and tobacco consumption (89).[3] Marriage and work were also key aspects to the salaryman masculinity (91)[3], as salarymen were expected to be productive at work and reproductive in creating and supporting a family (92).[3].

Housewife femininity was the complementary femininity to the salaryman masculinity (90).[3] Wives of salarymen usually stayed at home, taking care of the domestic duties and children, so that their husbands could dedicate their life to work (92).[3] They were also put in a position of dependence on their husband, as their wealth and social status depended on the success of their husbands (93).[3]

In the 1990s, Japan's bubble economy burst, which left Japan in an extended period of economic stagnation that challenged the salaryman masculinity and this family model (93).[3] As a result of economic stagnation, Japan was characterized by low economic growth and rising unemployment (93).[3] Corporate restructuring and downsizing occurred alongside a nationwide decrease in the number of permanent employment positions that companies could provide (93).[3] This meant that there were less permanent positions for recent graduates, meaning that young men had to turn to other non-permanent forms of employment (93),[3] including part-time or temporary work (76).[2] This counter-acted the salaryman masculinity, as young men became less economically affluent and less focused on their full-time positions (93).[3] The rising prominence of herbivore masculinity, and subsequently the perceived demise of salaryman masculinity, has only been furthered by the spread of gender equality ideals and the passage of gender equality legislation in Japan (100).[3]

Attributes

Herbivore men are known to be the counter-masculinity to the hegemonic masculinity (89).[3] This has ultimately rendered herbivore masculinity a soft masculinity. As a result of this, there are many negative connotations associated with herbivore masculinity and the traits of herbivore men.

In relation to salarymen, herbivore men are less luxurious consumers, less professionally ambitious, less interested in romantic relationships and more emotional and passive (89).[3] Furthermore, although grooming and personal care regimes are central to both salarymen and herbivore men, these regimes are more emphasized and central to herbivore masculinity (95).[3] While the salaryman spends an excessive amount on tobacco and alcohol consumption (89),[3] herbivore men usually do not spend any or much on this, as they prefer to drink tea over alcohol (73).[2] Also, while salarymen only really form relationships with women based on sexual desire and are emotionally inarticulate in these relationships, herbivore men are able to form meaningful platonic friendships with women that are not centered around any romantic interest (95).[3] Salarymen are also more aggressive and assertive in their daily life and pursuit of women, while herbivore men are more passive and shy (71).[2]

Other typical and notable characteristics of herbivore men are their slim physique, disinterest in forming romantic relationships (89),[3] increased fashion consciousness (73),[2] and increased interest in cosmetics, grooming and personal care (97).[3]

Scrutiny in Japan

Society and the government have increasingly blamed the rising number of herbivore men for recent issues in Japan.

According to the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, Japan has seen a decrease in population, with only 1.03 million births in 2013 (75).[2] With a rapidly aging society and birth rates that are too low for demographic replacement,[4] it has been predicted that Japan could lose a third of their current 127 million population by 2060 and could also be reduced to a population of 42.9 million by 2110 (75).[2] Therefore, with Japan's declining birth rate, the government has vilified herbivore men, scapegoating them as a contributing factor to the country's declining birth rates (75).[2] The government has enacted policies, including payouts and free healthcare for couples having children, in hopes of increasing Japan's birth rates and also combating the phenomenon of herbivore masculinity (75).[2]

Furthermore, as a result of their less affluent economic status, herbivore men have been blamed for low sales in certain industries, like the automobile and alcohol industry (77).[2] When car sales in the country dropped in 2008 and as alcohol sales fell, the media and industries blamed herbivore men, as herbivore men are considered to be poor consumers (77).[2] This connotation, a contrast from the salaryman's luxurious consumption, is due to the idea that herbivore men only spend money on practical items because of their less affluent positions (77).[2]

Canadian Masculinity

Research indicates that there are three prominent types of masculinity present in the West (64).[5] The three masculinities include muscularity, metrosexuality and laddism, which all contribute to hegemonic masculinity in some way (64).[5]

The history of muscularity is described to have began with fur traders in Canada, who were required to do a lot of heavy lifting and paddling (65).[5] These aspects of the fur trade promoted a strong and tough image of masculinity (65).[5] Muscularity remained prominent, as there was a movement of remasculinization after the Vietnam War that was displayed through violent and aggressive behavior (65).[5] This was a way for men to compensate due to the fact that women were beginning to have a more dominant role in society (65).[5] This remasculinization has extended to gym culture, which has been perpetuated by increasingly muscular action figures and in movies with lead actors like Arnold Schwarzenegger (65).[5]

Metrosexuality emerged in the 1970s and developed in the 1980s (65).[5] Rather than focusing on dominance over women, children, and other men, this form of masculinity involves paying closer attention to fashion and how one grooms themselves, maintaining one's self-presentation (65).[5]

Laddism is said to have come from the United Kingdom in the 1990s (65).[5] This type of masculinity emerged as a response against feminist movements (65).[5] Laddism encourages sexist behavior, which includes sexually objectifying women, and living a lifestyle filled with fast cars, heavy drinking, and promiscuity (65).[5]

Regardless of how these masculinities differ, each is displayed in a way that complies with the image of hegemonic masculinity. Research on various publications indicated that metrosexual magazines represented men as having more money and status, while laddist magazines focused on men's sexual dominance over women (73).[5] This research proved the idea that different forms of masculinity used different elements of hegemonic masculinity to assert power and dominance over women (73).[5] Therefore it is evident that although Canada is portrayed as more egalitarian, hegemonic masculinity still dominates, as masculinities have shifted over the years but have still continued to promote the power and dominance over women that are characteristic of hegemonic masculinity.

The formation of the Western masculinities described have largely been attributed to the gay and feminist movements (65).[5] This differs from herbivore masculinity, which was more so related to economic stagnation and partially a result of shifting social landscapes (66).[2] Out of these three masculinities, herbivore masculinity in Japan is most comparable to metrosexuality.

Critical Notes

Attributes that have been attached to herbivore masculinity have been applied inconsistently among various scholars, as scholars have portrayed herbivore men as sexually active, yet inactive, and disinterested in marriage and relationships, yet also having long-term girlfriends (96).[3] While some researchers focused heavily on their increased fashion consciousness (73),[2] and grooming and personal care regimes (97),[3] others completely discount these aesthetic factors as crucial to herbivore masculinity (36-37).[6] Furthermore, of these attributes associated to herbivore men, most people in society found that what constituted a herbivore man was in fact his shyness and his disinterest for a relationship at that time in his life (37-38).[6] This is contradictory of what researchers have been focusing on in their study of herbivore masculinity, which includes largely the aesthetics of herbivore men and their disinterest for sexual intimacy and relationships in general.

Additionally, while all researchers tend to characterize herbivore men as young men in their 20s or 30s, most researchers do not address what happens to herbivore men as they age. It is evident that many herbivore men give the future serious thought, including future family planning, which goes against the suggestion that herbivore men are ambiguous about starting families (42).[6] This proves that herbivore males display the core ideas that make up the ideals of hegemonic masculinity, indicating that herbivore masculinity may actually just be a phase in one's life (42).[6]

Furthermore, there are other inconsistencies in this research, as the phenomenon of herbivore masculinity is reliant on the disinterest of Japanese men to pursue romantic relationships. Research does not focus on the interest of women and how this has shifted with the increase of herbivore men. This leads to the belief that even with this phenomenon, women are still pursuing romantic relationships with herbivore men. However, this is incorrect, as there is actually an increasing number of younger urban women who, like herbivore men, are refusing to marry and/or choosing not to have children.[4] Therefore, it can be understood that the change in attitudes of young men, regarding relationships, is also occurring in young women as well, but is seen as less of a phenomenon for them.

These inconsistencies could be largely due to a gap in existing research, as studies focus more on the phenomenon of herbivore masculinity rather than lived realities of actual herbivore men (98).[3] In relation to Canadian masculinity, it is evident that studies around herbivore masculinity dismiss the agency of herbivore men. Studies disregard the idea that Japanese men nowadays may not be interested in romantic relationships because they are too time and work intensive, as this is a rising reason as to why people in the U.S. are not pursuing monogamous relationships at the moment (97).[3]

Lastly, it is important to understand that a large proportion of studies on herbivore masculinity have broadly homogenized the masculinity and ideas of what constitutes a herbivore man (98).[3] Although many scholars make it seem as though herbivore masculinity is on it's path to taking over as the hegemonic masculinity in Japan, it is crucial to understand that it is not (46).[6] Just like the salaryman masculinity, herbivore masculinity includes utilizing different elements of hegemonic masculinity to assert power and dominance over women and reify the subordination of women (73).[5] Therefore, although herbivore masculinity is subordinate to salaryman masculinity, it is understood that on a hierarchy of gender relations, herbivore masculinity is still above any other femininity, including the housewife femininity (99). [3] This makes it evident that although herbivore masculinity may be a scrutinized form of masculinity, it is still considered more prestigious and socially above any form of femininity. Hence, just like salaryman masculinity, herbivore masculinity does not promote gender equality and instead sustains the unequal relationships between men and women (100).[3]

References

- ↑ Eigapedia. "Soshokukei Danshi (2010)." 2014. <https://eigapedia.com/movie/soshokukei-danshi>.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 Nicolae, Raluca. "Soshoku(Kei) Danshi: The (Un)Gendered Questions on Contemporary Japan." Romanian Economic and Business Review 9.3 (2014): 66-81.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 3.21 3.22 3.23 3.24 3.25 3.26 3.27 3.28 3.29 3.30 3.31 Charlebois, Justin. “Herbivore Masculinity as an Oppositional Form of Masculinity.” Culture, Society & Masculinities 5.1 (2013): 89-104.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Columbia University. "Japan's Modern History: An Outline of the Period." Asia for Educators. New York, 2009.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 Ricciardelli, Rosemary, Clow, Kimberly A. and White, Philip. "Investigating Hegemonic Masculinity: Portrayals of Masculinity in Men's Lifestyle Magazines." Sex Roles: A Journal of Research 63.64 (2010): 64-78.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Smitsmans, Jef, and Lund University. "The Resilience of Hegemonic Salaryman Masculinity: A Comparison of Three Prominent Masculinities." Centre for East and South-East Asian Studies 51.51 (2015):1-55.