Gulabi Gang

Feminism in India

As scholar Geetanjali Gangoli notes, although women’s groups and questions of women’s oppression have been an element of “anti-colonial nationalist movements [since] the late nineteenth and early twentieth century” in India, only beginning in the 1970s were feminist organizations that laboured primarily for women’s welfare created (15)[1]. Emerging Indian feminist groups of the 1970s and 1980s were organized in protest against nationwide problems of “police and state initiated violence against women” (21)[2]. As Gangoli contends, this is unsurprising considering that the women’s movement in India was catalyzed by the “gang rape of a tribal girl [named] Mathura” by a number of police at a police station, an incident which was later excused by the legal system (21)[3].

Indeed, a number of feminist groups emerged across India in the 1970s and 1980s to protest solely against the injustice of custodial rapes, like the rape of Mathura, including one prominent Mumbai-based group called the FAR (Forum Against Rape) (21).[4] By 1982, the FAR turned into the FAOW (Forum Against Oppression of Women), which took up the mission of bringing many Indian women’s issues to light, such as “sexual harassment in the workplace and in public spaces, dowry related violence and murders, domestic violence, representation of women in the media, discrimination against women in civil and criminal law, rights of working class women, including sex workers, women’s health and reproductive rights, and support the work of social movements working against poverty class and caste oppression” (24).[5] A year before, in 1981, another Mumbai-based feminist group called The Women’s Centre had emerged, and as the name implies, this group was focussed on giving support to women in times of emergency (24).[6] The Women’s Centre has employed both legal and non-legal means of dealing with domestic abuse, where non-legal modes of action can entail launching public protests outside the residences of violent, abusive men in order to embarrass them and produce a community atmosphere of intolerance towards maltreatment of women (24).[7]

According to Gangoli, many feminist groups in India “have an important, though troubled relationship with the law,” (30) and often do not trust “legal methods or the legal system, choosing to use non-legal methods of negotiation” (26).[8] To be sure, the judiciary system and its tendency towards corruption, as seen in the Mathura rape case, has been challenged by Indian feminists in the women’s movement from its beginning (30).[9] Given that this is the case, it is not shocking that the vigilante Indian feminist group Gulabi Gang was formed and has risen to international visibility. Non-legal methods of resolution have become a part of the feminist tradition in India, and indeed have grown out of a dire need to combat injustice, which primarily involves fighting back against men who threaten women’s basic survival.

Gulabi Gang

The Gulabi (a Hindi word for pink) Gang was founded in 2006 by Sampa Pal Devi. Also known as ‘Pink Vigilantes,’ the group is comprised of hundreds of women in India, and members dress in pink saris to be easily identified as defenders of disadvantaged women (312).[10] One of the primary aims of the group’s so-called vigilantism is to target abusive husbands and unethical authorities by “beating [them] up or [threatening them with] whatever weapons are available including walking sticks, iron rods, axes, and even cricket bats” (312).[11] The group has halted child marriages, coerced policemen into monitoring domestic abuse cases, and caused roads to be constructed by pulling the administrator in charge “from his desk to the dust track in question” (312).[12] In interview, the leader of the group has illuminated their cause, stating that “Nobody comes to [womens’] help in these parts. The officials…are corrupt and anti-poor. Sometimes we have to take the law in our hands. At other times, we prefer to shame the wrongdoers...Village society in India is loaded against women. It refuses to educate them, marries them off too early, and barters them for money. Women need to study and become independent to sort it out” (318).[13]

Although media sources often sensationalize the type of vigilantism at work in the Gulabi Gang, feminist scholars White and Rastogi posit that “women’s movements, like most social movements, should make use of diverse tactics including reformist, radical, non-violent and, yes, even violent tactics depending on the sociopolitical context” (318).[14] As they note, most of the women who the Gulabi Gang defend are “already excluded from the barely functioning aspects of the judicial systems in their localities” (318).[15] Despite local and international laws, the civil liberties of men are prioritized over those of lower-caste women due to cultural norms that allow for sustained prejudice against them (318).[16] Whether women in the Gulabi Gang choose to retaliate or not, it is certain that their lives are already defined by violence, as “multiple patriarchies inadvertently and repeatedly condone men’s violence against women” (318).[17] In response, some women have decided to interrupt these toxic power relations by reclaiming their rights to defend themselves with violent means (318).[18] As White and Rastogi note, while the use of violence alone will not fully halt male-domination in India, it can be a valuable tool for liberation and self-defence alongside the pursuit of more possibly lasting means of female freedom (318).[19]

Domestic Violence in India

According to the Encyclopaedia of Domestic Violence and Abuse, women in India suffer from high incidence of domestic violence (242).[20] In 2002, the International Center for Research on Women reported that “45 percent of Indian women are slapped, kicked, or beaten by their husbands,” and that half of abused women were injured when pregnant (242).[21] About 75 percent of women who reported being abused have tried to commit suicide. Significantly, violence against women has been reported by women of all areas of India, all spiritual affiliations, and all classes (242).[22] Scholar Laura Finley notes, “As in some other third world countries, there are numerous economic, political, and social factors that contribute to rates of domestic abuse” (242).[23] He continues, “In addition to limited economic, political, and social resources, women in India experience institutional oppression in the form of traditional, patriarchal family structures; the caste system; and in their religious freedom” (242).[24]

Women’s advocates assert that the dowry system is one of the primary reasons women face high levels of violence in India (243). The system was established around year 100 BCE to encourage gift and property exchange from females’ families to males’ families in marriage, enabling patriarchal control of resources, but evolved into “a system of…negotiation and bargaining, rather than [promoting]…voluntary gift[s]” (243).[25] The system has endured and puts women at risk, as grooms’ families frequently mistreat wives when they receive what they judge to be dowries of insufficient value (243).[26]

Pink Saris (2010)

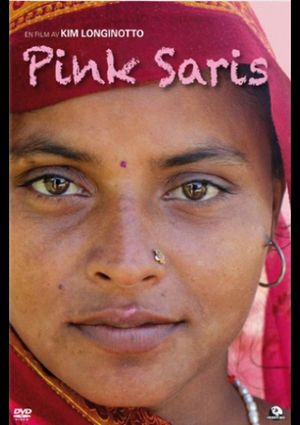

In 2010, director Kim Longinotto made the film Pink Saris documenting the work of the Gulabi Gang and Sampat Pal Devi.

References

- ↑ Gangoli, Geetanjali. Indian Feminisms: Law, Patriarchies and Violence in India. Abingdon, GB: Routledge, 2007. ProQuest ebrary. Web. 7 August 2016. http://site.ebrary.com/lib/ubc/reader.action?docID=10211388&ppg=28

- ↑ Ibid. http://site.ebrary.com/lib/ubc/reader.action?docID=10211388&ppg=28

- ↑ Ibid. http://site.ebrary.com/lib/ubc/reader.action?docID=10211388&ppg=28

- ↑ Ibid. http://site.ebrary.com/lib/ubc/reader.action?docID=10211388&ppg=28

- ↑ Ibid. http://site.ebrary.com/lib/ubc/reader.action?docID=10211388&ppg=28

- ↑ Ibid. http://site.ebrary.com/lib/ubc/reader.action?docID=10211388&ppg=28

- ↑ Ibid. http://site.ebrary.com/lib/ubc/reader.action?docID=10211388&ppg=28

- ↑ Ibid. http://site.ebrary.com/lib/ubc/reader.action?docID=10211388&ppg=28

- ↑ Ibid. http://site.ebrary.com/lib/ubc/reader.action?docID=10211388&ppg=28

- ↑ White, Aaronette, and Shagun Rastogi. "Justice by Any Means Necessary: Vigilantism among Indian Women." Feminism & Psychology, vol. 19, no. 3, 2009., pp. 313-327. Web. 7 August 2016. http://fap.sagepub.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/content/19/3/313

- ↑ Ibid. http://fap.sagepub.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/content/19/3/313

- ↑ Ibid. http://fap.sagepub.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/content/19/3/313

- ↑ Ibid. http://fap.sagepub.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/content/19/3/313

- ↑ Ibid. http://fap.sagepub.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/content/19/3/313

- ↑ Ibid. http://fap.sagepub.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/content/19/3/313

- ↑ Ibid. http://fap.sagepub.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/content/19/3/313

- ↑ Ibid. http://fap.sagepub.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/content/19/3/313

- ↑ Ibid. http://fap.sagepub.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/content/19/3/313

- ↑ Ibid. http://fap.sagepub.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/content/19/3/313

- ↑ Finley, Laura L. "India and Domestic Abuse." Encyclopedia of Domestic Violence and Abuse. Ed. Laura L. Finley. Vol. 1. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2013. 242-246. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 7 Aug. 2016. http://go.galegroup.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CCX3161600089&sid=summon&v=2.1&u=ubcolumbia&it=r&p=GVRL&sw=w&asid=016ed0b68a8d6762bbd2271d8eb77c98

- ↑ Ibid. http://go.galegroup.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CCX3161600089&sid=summon&v=2.1&u=ubcolumbia&it=r&p=GVRL&sw=w&asid=016ed0b68a8d6762bbd2271d8eb77c98

- ↑ Ibid. http://go.galegroup.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CCX3161600089&sid=summon&v=2.1&u=ubcolumbia&it=r&p=GVRL&sw=w&asid=016ed0b68a8d6762bbd2271d8eb77c98

- ↑ Ibid. http://go.galegroup.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CCX3161600089&sid=summon&v=2.1&u=ubcolumbia&it=r&p=GVRL&sw=w&asid=016ed0b68a8d6762bbd2271d8eb77c98

- ↑ Ibid. http://go.galegroup.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CCX3161600089&sid=summon&v=2.1&u=ubcolumbia&it=r&p=GVRL&sw=w&asid=016ed0b68a8d6762bbd2271d8eb77c98

- ↑ Ibid. http://go.galegroup.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CCX3161600089&sid=summon&v=2.1&u=ubcolumbia&it=r&p=GVRL&sw=w&asid=016ed0b68a8d6762bbd2271d8eb77c98

- ↑ Ibid. http://go.galegroup.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CCX3161600089&sid=summon&v=2.1&u=ubcolumbia&it=r&p=GVRL&sw=w&asid=016ed0b68a8d6762bbd2271d8eb77c98