Documentation:Open Case Studies/FRST522/The Flathead Valley - a Forest of the Ktunaxa Peoples of Canada and the Kootenai Peoples of the United States

The Flathead Valley: a Forest of the Ktunaxa Peoples of Canada and the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Peoples of the United States

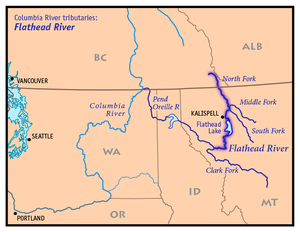

The Flathead Valley, which extends between the Province of British Columbia (BC) in Canada and the State of Montana in the United States (US), is part of the traditional and unceded territory of the Ktunaxa Peoples and the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes (CSKT). This area has faced a great deal of both natural resource extraction interest and environmental interest over the past hundred years. For the past two decades there has been a large movement to bring the area under environmental protection by designating a portion as a National Park, and the rest under other conservation designations. The involvement of both the Ktunaxa Peoples and the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Peoples has varied since the inception of colonization; however the historical and current context of the Indigenous people to the Flathead are critical to include and understand in moving forward with a vision for the pristine area.

Description

Indigenous People of the Flathead Valley

The Ktunaxa and CSKT Peoples have lived and travelled through the Flathead Valley since time immemorial, and archaeological evidence dating back over 10,000 years further supports this [1]. Although today the Ktunaxa and Kootenai Peoples are considered separate groups, especially as they reside in different countries; prior to colonization the Ktunaxa and Kootenai Peoples were considered to be from the same ethnic group – sharing one language [1]. With respect to historical context, Ktunaxa is used in this part to be inclusive of both the current Ktunaxa in Canada and the Kootenai in the US. Within what is now the BC border, Ktunaxa were known to occupy approximately 70,000 square km, not including their traditional territory in parts of current day Idaho, Montana, and Washington [1].

During the beginnings of colonization within the region, both the governments of Canada and the US split the Ktunaxa Peoples. In Canada they were split into five separate bands in the Indian Act, known today as the ?akisqnuk, ?aq’am, Tobacco Plains, Lower Kootenay, and Shuswap [1]. The Shuswap band was unique in that it consisted of both Ktunaxa and Secwepemc Peoples. The merging of two ethnic groups into one also occurred on the US side of the border. During the discussions of the 1855 Hell Gate Treaty, the Governor was ignorant to the fact that the Bitteroot Salish and Pend d’Oreille were significantly different from those of the Kootenai and thus labeling all Indian cultures alike grouped them together into the Flathead Reservation [2]. The three tribes formed the CSKT, and those of the Kootenai residing in Idaho later formed the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho [1]. Due to the mix of ethnic groups during those discussions, they were known to have been largely misunderstood due to poor translation of language and cultural meanings [2]. As the Indigenous Peoples of the Flathead Valley did not view land as property the way the settlers did, the differences in perspectives unfortunately became clear with establishment of property borders. What was lost with identifiable borders is that both Indigenous People and nature did not follow this way of thinking. Traditional trails and routes, such as the Buffalo Cow Trail, had been widely used to pass through the Continental Divide in the Flathead – but the countries of Canada and the US drew an invisible line thus preventing a large part of the traditional way of life [1].

Significance of the Flathead Valley

The establishment of borders has had unfortunate consequences for ecosystems and their ecology, as those systems extend past what one country can control: the Flathead Valley is one such example. The Flathead Valley is one of the most biodiverse ecosystems in North America and the Indigenous Peoples were not the only ones to acknowledge it. Upon arriving in the Flathead in 1901, explorer George Bird Brinnell saw the diversity in ecosystems and coined the term for the area ‘Crown of the Continent’ [3]. The convergence of ecosystems representing the boreal, grasslands, Pacific Northwest, and southern Rocky Mountains has made the Flathead Valley one of the most critical landscapes connecting migratory wildlife and genetic diversity [3] [4]. This area is home to the largest inland population of grizzly bears and one of the last wild gravel bed river basins in Canada [4].

Unfortunately, this pristine wilderness has naturally also attracted the interest of resource extraction. Despite efforts to conserve this region, the Flathead Valley continues to be threatened by plans for industrial logging, new road access, rock quarrying, mountain top removal coal mining, unsustainable forest practices, residential and recreational development, and the hunting of ecologically important species [4][5]. Although it appears that a lot of the conservation effort and work has been steered by the various levels of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), it is stated in Sierra Club BC’s website that the wishes for the Flathead Valley are in alignment with the wishes of the Ktunaxa First Nation [4].

Timeline of Resource Extraction in the Flathead Valley[3][6]

- 1950’s

- Although resource extraction interest started close after the time the explorer David Thompson had come through the area, large mining proposals are considered to have began in the early 1950’s

- 1970’s

- Assessment work for mining operations began in the area of Cabin Creek by Sage Creek Coal Ltd

- 1990’s

- Despite two decades of attempts to pursue exploration in the area, Sage Creek Coal Ltd. finally conceded and pulled out their interest due to economic circumstances

- 2003

- BC Lt. Governor speech called for BC to open up every region and economic sector to development and investment

- Cline Corporation applied for 12 coal exploration licenses through BC Ministry of Energy and Mines, for a location not far from the previous proposed site by Sage Creek Coal Ltd.

- Same month as Cline Corporation applications, BC Premier Gordon Campbell and Montana Governor Judy Martz signed Environmental Cooperation Agreement

- Later in the year, BC Government gave Cline Corporation the green light to build roads and test drill 90 tons of coal, but failed to notify the State of Montana

- 2004

- In July the BC Government put coalbed methane lease rights on the auction block

- This auction ended without attracting any bids

- 2009

- Summer of 2009 an investigative team was sent to the Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park

- This was a response to the coalbed methane leases being put on auction block, and over 53,000 people from Canada and the United States asking the United National Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) to address the environmental concerns of proposed mines

- Late 2009 the World Heritage Committee released its findings from the investigation

- 2010

- Lt. Governor Steven Point announced the Flathead River Valley would be off limits to mining and energy extraction

- Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) is signed between the Province of BC and the State of Montana with witnesses from Ktunaxa First Nation and the CSKT

- Largest leaseholder in the North Fork of the Flathead, ConocoPhillips, voluntarily gave up its interest in 108 oil and gas leases (169,000 acres)

- More leases by other companies continued to be voluntarily given up

- Allen and Kirmse, Ltd. (approximately 50,000 acres)

- Anadarko released interest with leases partially owned with ConocoPhillips

- XTO Energy (21,000 acres)

- BP (1,843 acres)

- 2011

- Early 2011, the Nature Conservancy of Canada and the United States pledged to provide funding to retire oil gas leases on the Canadian side of the border

- Four more energy companies voluntarily gave up their claims on oil and gas leases (15,000 acres)

- Approximately 215,000 acres of previously held claims of interest have been voluntarily give up

- September – Flathead Watershed Area Conservation Act is passed in BC legislature

- 2012

- Montana Senator introduced the Transboundary Flathead Basin Protection Act, although this still needed to be passed by the US Senate.

- 2014

- December - North Fork Watershed Protection Act was passed in the US Senate

Tenure Arrangements

The Flathead Valley and traditional territory of the Ktunaxa has been divided over the years between land designations of:

- International UNESCO Peace Park

- National Parks

- National Forest

- Federal and Crown Land

- Provincial Parks

- Residential Communities

- Conservation Easements and Properties

- Private Land

- and Indigenous Reservations

The land designations have specific tenure arrangements, and sometimes have multiple types of tenure arrangements for different stakeholders and type of activity. Tenure can be described as an interest or right to hold or occupy property; and can refer to rights of specific resources (timber, minerals, or water). Land can be accessed by more than one party (ex. guide outfitting, tree farm, trap line, and mineral claims), and involve license types of occupation, statutory rights of way, permits and leases, convey specific rights, privileges or obligations [7].

The tenure arrangements for the area changed upon the passing of the Flathead Watershed Area Conservation Act in 2011 for BC and the North Fork Watershed Protection Act in 2014 for Montana. The two acts both prevent mining and energy extraction within the Flathead Watershed.

International

The designation of Waterton-Glacier as the First International Peace Park through UNESCO World Heritage placed two National Parks, one in Canada and the other in the US under a higher international designation. Despite the higher designation the properties still followed National Park tenure arrangements.

The Indigenous population of the area appeared to have limited involvement in the consultation and process of this land designation, as the original 2003 Environmental Coordination document signed between the two countries did not involve the Ktunaxa or CSKT. However, in the signing of the 2010 MOU, both the Ktunaxa and CSKT were invited to sign and participate at table discussions regarding the International Peace Park [1]. The 2010 MOU also acknowledged that the area had been important for the use of hunting, fishing, trapping, gathering, recreation and as a travel corridor and that these activities would continue for Ktunaxa and CSKT[8]

International borders also impact tenure arrangements to the currently split groups of the Ktunaxa. A Ktunaxa elder has explained that the border creation in 1861 previously meant nothing to his great grandparents who continued to cross the border to continue using traditional trade and travel routes[9]. Since the 1930s authority over border control became stricter in the region and those that used to use their right to cross have ceased not wanting to face jail time [9].

National Parks

The Flathead Valley as mentioned above has two National Parks, the Waterton National Park in Canada and the Glacier National Park in the US. As well as mentioned, there is considered a lack of involvement or consultation with respect to their original development and designation. In Canada all forms of commercial mineral activities are prohibited in National Parks[10]. In the US no grazing, mining, forestry, hunting or off-road vehicles are allowed and even regulations for visitors can be quite limited for their National Parks[11].

National Parks globally are designated under the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as Protected Area Management Categories I to II and although it does not equate for every national park – the IUCN does support a ban on mining on IUCN Protected Area Management Categories from I to IV[10].

If the interest is there to expand a National Park in Canada, the forced sale of lands needed for the purpose of expanding is possible; however, tenure arrangements for all mineral permits, claims, and lease holders – as well as big game hunting outfitters remain intact[10].

National Forest (US Only)

Only one National Forest resides within the Flathead Watershed in the state of Montana and it is aptly named the Flathead National Forest. National Forests are different designations than a National Park, despite the similar name. Hunting, logging, mining and grazing are all permitted and allowed within a National Forest[11].

National Forests can have their ownerships transferred to the individual states, however this transaction is seen as decreasing the protection[11]. There is no mention of specific tenure arrangements with the CSKT.

Specific to the Flathead National Forest, over 1 million acres is a National Wilderness Preservation System where roads, timber harvesting and motorized travel are not permitted; however the remaining 1.3 million acres are open for timber harvest, recreation-based motorized travel, and other activities [1].

Federal and Crown Land

Federal land in the US and Crown (federal) land in Canada differ on legislative tenure arrangements. In Canada for arrangements related to resource extraction they also differ on the type of resource extraction (i.e. forestry versus oil/gas/mining).

With respect to Crown land and the mining, oil, and gas industry[7]:

- Neither government or person with a non-intensive occupation or use of unoccupied Crown land is consider a land owner (as defined by OGAA and PNG Act)

- Crown owns majority of subsurface rights

- Ministry of Natural Gas Development (MNGD) responsible for PNG tenure

- Separate from Ministry of Forests, Lands, and Natural Resource Operations (MFLNRO)

For Federal land in the US much of the application for mining, oil, and gas industry is similar; however the 1872 Mining Act also gives hardrock miners the right to claim federal land for mining purpose and mine without paying any royalties[12].

Over the years, both the Federal and Provincial governments in Canada have been working with the Ktunaxa to build tenure arrangements in their traditional territory and have come together to build forestry agreements and areas of co-management. However problems still exist in the area of tenure arrangements with ongoing treaty negotiations, minimal level of revenue sharing, and minimal level of tenure available to First Nations[13]. The following is the most current list of Forestry Agreements between the Ktunaxa Nation and Province of BC with regards to Crown land[14]:

- Ktunaxa Nation Forest Consultation & Revenue Sharing Agreement (2017)

- Ktunaxa Nation Agreement to Amend the Community and Economic Development Agreement as it relates to the Forest Revenue Sharing Project Appendix (2016)

- Ktunaxa Nation Forest Revenue Sharing Project Appendix (2014)

- Ktunaxa Nation Forest Revenue Sharing Agreement (2013)

- Ktunaxa Nation Forest Tenure Opportunity Agreement (2013)

- Amendment (2007)

- Ktunaxa Nation Mountain Pine Beetle Agreement (2010)

- Ktunaxa Nation Mountain Pine Beetle Agreement (2009)

- Ktunaxa Nation Wildfires Agreement (2003)

- Amendment (2006)

- Ktunaxa Nation Interim Measures Agreement (2003)

Of special note, is the Community Forest Agreement between the Province and Nupqu Development Corporation (owned by Ktunaxa Nation). A 25 year agreement was signed for the forest management of the area known as the Dominion Coal Blocks in the Flathead.

Provincial and State Parks

The only Provincial Park in BC is located on the upper corner of the Waterton National Park, and is called the Akamina-Kirshenina Provincial Park. This area was acknowledged as being part of the traditional territory of the Ktunaxa/Kinbasket Tribal Council; however, limited consultation and involvement occurred in the development of the Provincial Park[15]. No information on First Nations traditional uses could be listed for this area due to the lack of consultation and involvement.

Provincial Parks do not have the same tenure arrangements as National Parks do. Provincial Park lands can split into two categories of Class A and Class B, where Class A prohibits all forms of mining[10]. Mineral exploration and development is permitted within some provincial parks, and if not permitted can get around this by designating a portion of the park as Class B.

There are several state parks within the Flathead Valley: Flathead Lake, Lake Mary Ronan, Whitefish Lake, Placid Lake, and Salmon Lake [1]. The Montana state government runs the State Parks; currently an arrangement exists between the state and private landowners to cease further development access [1]. The Trust Lands Division allows timber harvesting, grazing, recreational use, commercial leases, and cabin site leases in order to generate revenue [1].

Residential Communities

A few small communities reside within the Flathead watershed within the State of Montana, but are also located within the boundaries of the Glacier National Park and therefore would be subjected to similar tenure arrangements as the National Park.

A greater amount of communities and cities reside just outside the Flathead watershed in both BC and Canada, but as these are not directly in the watershed they have not been included.

Conservation Areas

Many conservation easements and properties exist within the Flathead Valley, however each have their own tenure arrangements to suit the needs and wants of those involved. Considering that a great deal of the objectives is suited towards conservation and preservation, tenure arrangements with respect to resource extraction or damage are unlikely to exist for these properties.

Private Land

While some private land has entered into easement agreements with NGOs, the private land is also subject to treaty negotiations on the Canadian side. There are ongoing Ktunaxa treaty negotiations, which would change the tenure arrangements for these areas. Tenure arrangement for these areas is also subject to whether extension of a National Park occurs as mentioned in the National Parks section. The establishment of the Glacier National Park continues to have 418 acres of privately owned parcels due to the prior ownership in the area.

Reserve Lands

Reservation lands on the Canadian side have no been included in this section as they are not within the Flathead watershed. The Flathead Reservation for the CSKT in Montana is located at the end of the Flathead River. The original treaty land in 1855 has since been fragmented due to the Flathead Allotment Act that opened up the reservation to non-tribal members in 1910[16]. The CSKT has developed their own resource agreements for both tribal members and non-tribal members for the reservation area. One of the principles sources of income for the Tribe are from timber industry sales[16].

Administrative Arrangements

In this context administrative arrangement refers to the management control and decision-making power for the specified land designation.

International

In regards to the International Peace Park, the administrative arrangement is still held by both Countries National Park arrangements. The MOU signed by both countries recognized that the Flathead River is within the Ktunaxa territory and that they have a documented historical connection to the area[8]. Also noted in the MOU is that the CSKT have effectively managed the areas water and land sustainably for thousands of years [8]. Although acknowledgement is given regarding the territory, ultimate authority still lies within National Park arrangements.

The IUCN designation of the International Peace Park doesn’t change the administrative arrangement, but if management recommendations are not followed the designation could be lost.

National Parks

Administrative authority for Waterton National Park in Canada is held by Parks Canada and for the Glacier National Park in the US the National Park Service holds the authority.

National Forest (US Only)

The US Forest Service, apart of the federal Department of Agriculture, manages the Flathead National Forest. The Flathead National Forest is 43% of the lands within the Flathead watershed, meaning that a lot of nearly half the land decision lies within the US Department of Agriculture[1].

Federal and Crown Land

Canada’s National Parks are run by Parks Canada, this federal department has administrative arrangement for the Waterton National Park. Similar to Canada, the National Park Service out of the US Federal Department of the Interior has administrative authority for the Glacier National Park.

As mentioned in the Tenure Agreements, there are current ongoing treaty negotiations and these would change administrative authority on the Canadian side. However, under section 35 of the Constitution Act of 1982, the government still holds the right to encroach on Aboriginal Title if they can justify broader public interest[13].

Provincial and State Parks

The Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development (MFLNRO) manage BC Provincial Parks in accordance with the Canadian Forest Practices Code with respect to timber, mining, grazing, wildlife, watershed protection, and recreation[1]. The Akamina-Kishinena Provincial Park has been managed mostly for backcountry recreation and wildlife habitat[1].

The Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks along with the Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation manage several state parks and the Trusts Lands Division (Flathead Watershed Sourcebook, 2016).

Residential Communities

Although residential communities must comply with regulations of the National Park, County Parks are managed and maintained by the Flathead Department of Parks and Recreation[1].

Conservation Areas

Administrative authority is largely dependent on location, type, and NGO for the conservation properties. Many are co-managed between multiple groups, or are easements on private land.

Private Land

A large portion of the private land in the Flathead Valley is used for timber production, with the three largest owners being: Plum Creek Timber Company, F.H. Stoltze Land and Lumber Company, and Montana Forest Products[1]. The largest private owner, Plum Creek Timber Company, manages their 256,000 acres through the Sustainable Forestry Initiative, Montana Forestry Best Management Practices, and the Native Fish Habitat Conservation Plan[1].

With private land, eminent domain has the potential to be applied in both Canada and the United States. Application of eminent domain would require compensation and reason for the purpose of benefiting the general public, but would remove the private owner from administrative authority.

Reserve Lands

The Flathead Reservation was established by the Hellgate Treaty, however over half a million acres were lost and passed out during the ownership land allotment[17]. The land and natural resources are managed by the CSKT with comprehensive resources plans since 1996[1]. The CSKT also established 92,000 acres of the reservation to be managed as the Mission Mountains Tribal Wilderness: the first wilderness to be formally reserved and protection by a tribe[1].

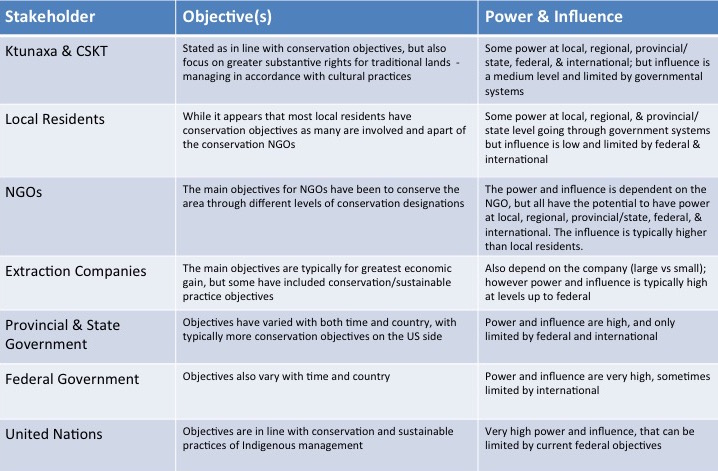

Stakeholders

The stakeholders involved with the Flathead Valley, can be split into those affected and those interested.

The affected stakeholders are the Indigenous Peoples of the area and the current local population of those in and near the Flathead Valley. The Indigenous Population in Canada is said to have recognized Aboriginal rights, but there have been debates on the power as Canadian law continues to be held supreme (Hanson, 2009). So while Indigenous Peoples of the Flathead hold power at all levels – their power is considered relatively low compared with that of federal law. The local residents who have since moved into and near the Flathead Valley have formed many of the existing NGOs and associations that are heavily involved in the conservation actions. Due to the relationship and connection between local residents and conservation NGOs and associations their power and influence are elevated. Local residents individually have low power, where they can vote or contact government officials for greater influence; together in large groups they have increased that power and influence.

Some of the large NGOs have been around since the early 2000’s to focus on strategic land conservation for the area (The Brainerd Foundation, 2017). Not all NGOs have the same objectives, but collectiveness have provided and even greater impact on influence and power for conservation. The NGO influence has a large part to do with extraction companies taking on more conservation objectives or releasing their interest and claims. The NGO power was comprised by the party in power for BC at many occasions and thus, it was the not the federal, but the international influence that changed the objectives of the province.

Discussion

Aims and Intentions

The aims and intentions for the land of the Flathead have varied between stakeholder groups and across time. There has been a large interest in extraction since the mid 1900s that increased in BC after economic downturn in the 1980s. The increased interest in extraction provoked a response in those wanting to preserve the area.

Over the past two decades the large aim of the Ktunaxa, CSKT, conservation NGOs, conservation associations, and local residents has been to designate the Flathead area with both preservation designations and others that would still satisfy the majority with activities of limited hunting, fishing, hiking and recreation. The aims are also in line with the Untied Nations international perspective that has given recommendations of looking at greater protection for the Flathead watershed.

Success and Failures

The failure in the Flathead Valley began with the beginning of colonization and the resulting stolen land of the Indigenous People. The failure continued with the continuation of colonization processes, such as the land allocation in the US and the residential schools in Canada. While success in this area is starting to be seen through more procedural rights being established by the Ktunaxa and CSKT; as well as, the moves towards gaining substantive rights, especially for the CSKT on their reservation land.

Unfortunately, despite the CSKT growing collaboration between the timber industry and sustainable practice and conservation – the rest of the Flathead had difficulties catching on. The failure by BC moving towards opening up and encouraging resource extraction in the early 2000s lead to one of the greatest successes. BC actions towards supporting resource extraction in the Flathead got the attention at the international level from United Nations. Canada was quick to address the report recommendations put forward from the assessment in 2009. Early in 2010 Canada submitted that they had addressed the issues raised and that resource extraction from mining would not occur in the Flathead Valley[18]. This success was later won in legislation nearly two years later for Canada, however a greater success was the backing and support by resource extraction companies. One of the highlights from extraction companies coming out in support of conserving areas of the Flathead was Teck Resources Ltd. purchasing 17,668 acres of private land for $19 million for conservation purpose[19]. The property will be co-managed between Teck Resources Ltd. and the Yellowstone to Yukon initiative for conservation, however there is still a way to go in order to the achieve the aims and intentions.

Issues and Conflicts

The greatest area of conflict for the Flathead Valley would be in the area of tensions between the economic benefits and conservation preservation. Economic benefits were directly pitted against environmental concerns in areas of water quality, and species protection [3]. Although the MOU took nearly 30 years to achieve, this provided some solutions to the area of conflict [3]. Removing future access to proposed coal bed methane, mountaintop removal coal strip mining, and oil and gas development in the Flathead was considered a large success; however, there is still uncertainty about the future[3]. The sudden shifts in politics have been found to have large impacts to conservation areas, such as the Flathead. Political changes at all levels can affect change, but the greatest impacts are felt from those with high levels of power: federal and provincial/state. Changes in these political levels have had a great deal of impact on the Flathead, as heated confrontations have even occurred between BC and Montana political officials pre-MOU[9].

Recommendations

The case of the Flathead Valley is hard to compare to other case studies as the unique dynamics between the Indigenous Peoples, dual countries, and international interests will be found no where else. An example in Brazil with the Caboclos people has been found to have similar aspects of colonization and land value; however, solutions from this case would still need to be adapted to the situation. Despite potential solutions in areas of Indigenous involvement, further conservation designations, and legislation changes; it remains difficult to evaluate as most of the information remains as government documents with limited public access[3].

Greater Indigenous Involvement

Indigenous involvement in government decision-making has been fairly limited globally, especially when it has come to land and natural resources. Like North America, areas in Brazil have faced similar types of colonization while their traditional land attracted commercial resource extraction interest, and international biodiversity concern. In the Varzea forests of Mazagao, Brazil the similarities between the Caboclos people and the Ktunaxa and CSKT of the Flathead Valley go beyond their colonization and land interest similarities. Both populations have had forest associations emerge from their local groups and have had little influence in the history of large over-arching decisions regarding their land[20]. The case of the Caboclos people have shown though the benefits of having those capable of doing specific task is better than having an over-arching body attempting to organize all aspects of forest management[20]. With the Flathead there has been many large NGO groups and a large over-arching government approach; identifying locals both Indigenous and non-Indigenous that have specific knowledge about the land should be a priority, so that the established skills can be utilized.

Another option taken from global Indigenous initiatives is that of Indigenous and Community Conserved Areas (ICCAs)[21]. Although ICCAs are not the only name for similar type set-ups, these areas give decision-making responsibility to Indigenous or local communities[21]. This type of management is supported both through the IUCN guidelines of protected areas, and by the Convention of Biological Diversity to which Canada has signed and ratified[21].

The supreme court of Canada has affirmed the importance of Indigenous perspectives in many of the legal proceedings that have been won in the past few decades; in addition they are internationally supported through the United Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP)[22]. Specifically in regards to the land, UNDRIP outlines free, prior, and informed consent ensuring space for Indigenous legal orders to influence decisions[22]. Indigenous perspectives and decision-making is imperative to the future of North America's environmental management, and this can be partially addressed through acknowledgement of Indigenous rights by implementing UNDRIP into law and legislation.

Supporting Designations

As has been stated in NGO websites, such as Sierra Club BC, the Ktunaxa supports the Flathead Valley being covered under multiple conservation designations. While designating a portion of the Flathead Valley, as a National Park appears to be a great option there have been debates on the effectiveness of National Parks for conservation objectives.

Despite the protection by Canada’s National Parks Act, human activities have been encroaching on National Parks and have been considered as severely threatening a large number of current parks[10]. In addition to human activities, mining activities are also occurring in close proximity to National Parks in Canada[10]. A need to address what is occurring outside the borders of parks is evident, especially in areas of possible spatial spillovers and non-randomly distributed protection[23].

Those in the Varzea Forests have looked at diverse ventures, to keep large economic interests at bay, which appears to be the similar strategy for the future of the Flathead Valley[20]. Implementing the desired designations looks to spread out human activities, resource extraction, and traditional use in different areas of the Flathead that appear likely to have a positive overall impact for conservation protection.

Legislation Changes

Changing the designation of the area by extending the National Park in Canada, or by establishing other Wildlife Management Areas in the US requires changes in legislation. However to ensure these designations do not fall victim to the poor conditions many parks are facing, transformative changes may require institutional change, technological innovation, behavioural shifts, and cultural change[24].

These transformative changes should be applied to looking at the ways in which ICCAs could be further supported. Currently legislation is considered a limitation in terms of support for voluntary designation and protection of terrestrial and marine ICCAs on Indigenous land and waters[25]. Australia has adopted laws that enable recognition and support of these protected areas, instead in Canada and the US only a degree of involvement from the Ktunaxa and the CSKT is considered for the future designations in the Flathead Valley. Giving de facto control to the Indigenous communities is in accordance with adaptive management strategies, and the Flathead Valley needs adaptive management, adaptive governance, and adaptive co-management in order to successfully achieve the desired aims[25][24]. The Flathead Valley is a complex problem where no optimal or single solution exists, but adaption is a problem-solving process that fosters the capture of learning needed in situations where the uncertainty of solutions are high [24]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 Flathead Watershed Sourcebook. (2010-2016). Brief history of the people. Web. Retrieved from http://www.flatheadwatershed.org/cultural_history/history_people.shtml

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Ojibwa (2011). The 1855 Hell Gate treaty. Web. Retrieved from http://nativeamericannetroots.net/diary/908

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Soucek, N. (2009). Trading off the benefits and burdens: Coal development in the Transboundary Flathead River Valley. (Unpublished Master of Science thesis). The University of Montana, 2009

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Sierra Club BC (n.d.). Flathead River Valley. Web. Retrieved from http://sierraclub.bc.ca/campaigns/flathead/

- ↑ Flathead Wild (n.d.). Protect it. Connect it. Defend it. Web. Retrieved from https://flathead.nationbuilder.com/

- ↑ Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (CPAWS) (2014). U.S. senate passes watershed legislation affecting B.C.'s Flathead River Valley. Web. Retrieved from http://cpawsbc.org/news/watershed-legislation-passed-affecting-flathead

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 BC Oil & Gas Commission (2015). Land owner's information guide for oil and gas activities in British Columbia. (Information Guide). BC Oil & Gas Commission.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Province of BC and State of Montana. (2010). Memorandum of understanding and cooperation on environmental protection, climate action and energy between the province of British Columbia and the state of Montana. Retrieved from http://www.gov.bc.ca/igrs/attachments/en/MTEnvCoop.pdf

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Kirkby, B. (April 6, 2010). Could Flathead Valley be Canada’s next National Park?. Web. Retrieved from https://www.theglobeandmail.com/life/travel/travel-news/could-flathead-valley-be-canadas-next-national-park/article4266390/

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Carey, P. (2008). Mining and Canada's National Parks - policy options: A case study of Nahanni National Park Reserve. (Unpublished Master of Environmental Studies thesis). Queen's University, 2008 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Carey" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Siler, W. (2015). Why congress can sell off our national forests, but not national parks. Web. Retrieved from https://gizmodo.com/national-park-vs-national-forest-your-public-land-expl-1697581346

- ↑ Shogren, E. (2016). A coalition hopes to halt gold mine proposals near Yellowstone. High Country News. Web. Retrieved from: http://www.hcn.org/articles/montana-businesses-want-washingtons-help-to-defeat-gold-mines-near-yellowstone

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Vancouver Island University. (2015). Statement of law regarding First Nations and forestry. Retrieved from http://www.fnforestrycouncil.ca/downloads/statement-of-law-re-first-nations-and-forestry.pdf

- ↑ Province of BC (2017). Ktunaxa Nation. Retrieved from Province of BC (2015). Ktunaxa nation. Retrieved from https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/environment/natural-resource-stewardship/consulting-with-first-nations/first-nations-negotiations/first-nations-a-z-listing/ktunaxa-nation

- ↑ Province of BC (1999). Management direction statement for Akamina-Kirshenina. Retrieved from http://www.env.gov.bc.ca/bcparks/planning/mgmtplns/akamina/akamina.pdf?v=1513306625615

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Natural Resources Department of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes (2017). Featured documents. Web. Retrieved from http://nrd.csktribes.org/

- ↑ Confederated Salish & Kootenai Tribes (2017). History and Culture. Web. Retrieved from http://www.csktribes.org/history-and-culture

- ↑ United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (2010). Convention concerning the protection of the world cultural and natural heritage: Item 7B of the provisional agenda: State of conservation of world heritage properties inscribed on the world heritage list (pp. 32). Web. Retrieved from: whc.unesco.org/document/104453&type=doc

- ↑ Yellowstone to Yukon (2017). Two wins for BC’s Flathead Valley. Web. Retrieved from https://y2y.net/news/updates-from-the-field/two-wins-for-bcs-flathead-valley

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Menzies, N. (2007). The Varzea forests of Mazagao, Amapa State, Brazil. Our forest, your ecosystem, their timber: Communities, conservations, and the state in the community-based forest management (pp.50). New York: Columbia University Press.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Smyth, D. (2015). Indigenous protected areas and ICCAs: Commonalities, contrasts, and confusions. Parks, 21(2), 73-84

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 The First Nations Leadership Council. (2013). Advancing an indigenous framework for consultation and accommodation in BC. Retrieved from http://www.fns.bc.ca/pdf/319_UBCIC_IndigActionBook-Text_loresSpreads.pdf

- ↑ Joppa, L. & Pfaff, A. (2010). Reassessing the forest impacts of protection. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, Ecological Economic Review.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Berkes, F. (2017). Environmental governance for the anthropocene? Social-Ecological systems, resilience, and collaborative learning. Sustainability, 9(1232). doi: 10.3390/su9071232

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Herrmann, T.M., Ferguson, M.A., Raygorodetsky, G., & M. Mulrennan (2012). Recongnising and supporting territories and areas conserved by Indigenous peoples and local communities: Global overview and national case studies. Web. Retrieved from: https://www.iucn.org/theme/protected-areas/about/protected-area-categories/category-ii-national-park

| This conservation resource was created by Braydi Rice. |