Course:HIST104/Coffee

Coffee Beans in Starbucks Mug | |

| Basic Information | |

|---|---|

| Introduction as Beverage | 15th Century |

| Origins | Ethiopia |

| Arrival in Europe | Italy |

| Grown | Near Equator |

Evolution and Spread of Coffee

Arabian traders first encountered coffee in Ethiopia around 1250 CE where herders had been grinding roasted beans into fat and producing the world's first form of energy bars for the long, cold desert nights spent watching their flocks. [1] These traders figured how to infuse its properties in boiling water and invented a drink that was both pleasant to sip as well as useful as an energy boost. These traders recognized its commercial potential and transported the plant to Yemen, where it was further cultivated and processed (by slaves) for sale on the expansive caravan trails of central Eurasia.[2] Coffee was on its way to the bazaar.

The Bazaar is both a product and reflection of Islamic society. Islam has its origins in the Levant, a region of the world whose empires had practiced global trade for centuries. As traders and merchants began to adopt Islam, the religion, along with material cargo, gained access to trading posts and bazaars in distant lands.[3] Therefore, wherever the exchange of goods took place, enclaves of Islamic influences could be found. Thus, as the very place where this exchange took place, one could call the bazaar the heart of Islamic societies - whether Persian, Turkish, Arabian or Uzbeki. Once adopted as a commodity to be traded, coffee therefore had access to the entire circulatory system of Islamic societies.

Once introduced to these bazaars, coffee promoted a kind of exchange that went beyond material wares; it promoted conversations and circulation of ideas. The introduction of the coffeehouse to the Arabian peninsula in the 13th century CE is an example of the variety of interactions that took place over coffee; businessmen met with associates to discuss ventures, friends socialized over a cup of "qahwa" after a day at the market[4] and Sufis used coffeehouses as venues to preach. These establishments also emerged as a kind of impromptu showcase of Islamic culture where travelling musicians and poets could expose their work. Coffee continued to be a vehicle of social exchange ever since. Meeting with friends at a local Starbucks is just the latest manifestation of the "ritual" of coffee consumption to facilitate social interactions from literary and political discussions, to dates between tentative lovers and friends "hanging out" to catch up on gossip.

From the 1500s, however, the Islamic revitalization of the Ottoman empire increasingly imposed government as a divine authority in order to ensure that Shari'a law was obeyed. [5] Shari'a law was seen as divine; questioning any law of policy based upon it was seen as heresy. Thus, as coffeehouses had become a meeting place for educated individuals to discuss politics, the Sultanate made the consumption of coffee illegal. Coffeehouses were raided and closed by governmental decree across the empire. In spite of this, coffee consumption continued as caravan-styled coffee houses followed trade routes. Eventually, rulers realized that coffee could not be stamped out and sanctioned alcohol as a more harmful and intoxicating substance. In large cities where locations are open until midnight, Starbucks' coffee often serves the same purpose - allowing people to socialize late into the evening without resorting to drinking at a bar.

The Spread of Coffee

France

- The Turkish Court sent Suleyman Mustapha Koca as ambassador to France in 1669. In search of interest from the French court, Koca introduced the court to coffee. Although Europeans had probably heard of the beverage prior to Koca's visit, its warm reception by the French court was coffee's breakthrough into European fashion.

- Louis XIV was presented a coffee tree in 1714, for his garden in Paris.

- Gabriel Mathieu de Clieu smuggled a sprout of coffee tree to Martinique, a French colony in the Caribbean. Ultimately, the plant flourished and 18 million coffee trees were grown there.

Netherlands

- The Dutch smuggled some plants out of the Yemeni port of Mocha in 1600s and began planting coffee on the island of Java in Indonesia.

Brazil

- Lieutenant colonel Francisco de Melo dispatched to French Guiana for share of coffee plant. De Melo befriended governor's wife whom slyly gave de Melo coffee tree seeds. De Melo then brought the coffee seeds back to Brazil.

Coffee, Plantations and Fair Trade

By the 1700s, coffee was making its way into the daily lives of Europeans as they acquired "a newfound taste for coffee." [6] A coffeehouse culture was growing and found comfort in eighteenth century London.

In 1662, London harbored one solitary coffeehouse, but by 1700, the city claimed more than two thousand of them; they grew so popular that patrons often used a favorite coffeehouse as their mailing address." [7]

The phenomena abruptly ended though, as Brits switched over to tea. However, coffee was not completely ruled out. As the Industrial Revolution came about, coffee found popularity once again in factories as managers learned that coffee boosted productivity.[8] The popularity of coffee began to grow once again and "by the 1950s, coffee had become a standardized product"[9] in post-war America.

While Europeans and Americans alike were sipping away on their morning coffees, not much thought was given to the origins of coffee. Situated largely in Latin America, coffee plantations depended on the labor of African slaves until slavery was abolished in Brazil in 1888.[10] After slavery was outlawed, immigrants took their places and continued to work in the plantations under terrible conditions for very poor wage. By the second half of the twentieth century, reports on the conditions of plantations are being brought to attention. The people who worked in them were living in poverty. The workers were paid by piece rate which amounted to often less than subsistence wages. Despite reliance on employers for housing, medical, education and food, workers' wellbeing was not a pressing matter to employers. One example in 1977 was that for every pound of coffee (which equates to about thirty minutes of labor by one worker), the wage was about thirteen cents. Migratory workers would be herded into vehicles, housed in sheds without walls, received no sick leave or medical attention and were fed tortillas and occasionally beans, while working for subsistent pay.[11] To make matters worse, any efforts on behalf of the workers to unionize were thwarted by owners by getting rid of jobs, denying access to water and firewood, and sometimes going as far as issuing death threats.[12] As people became increasingly aware of the situation in coffee plantations, there was a push for the betterment of working conditions of coffee workers and farmers.

By the late 1900s, "a movement was growing among coffee consumers to demand justice" for workers on coffee plantations.[13] The movement was called Fair Trade and the goal of the activists was to put "grassroots pressure on the big coffee retailers such as Starbucks to buy directly from cooperative farmers and pay a price that represents a living wage."[14] The concept of mainstreaming Fair Trade took off in the United States in 1998 with the formation of TransFairUSA, a third-party certifier of Fair Trade products.[15] Global Exchange, involved with TransFairUSA, is an organization that

"values the rights of workers and the health of the planet, prioritizes international collaboration as central to ensuring peace, and that aims to create a local, green economy designed to embrace the diversity of our communities."[16]

One of Global Exchange's most dramatic campaigns focused on Starbucks, specifically chosen because they were the largest coffee retailer in the United States, owning one fifth of all cafes in the country.[17] In 1999, Global Exchange approached Starbucks' then CEO Howard Schultz with a request for Starbucks to use Fair Trade coffee, but the company was hesitant. In response, Global Exchange organized several peaceful demonstrations in front of Seattle Starbucks stores. Then, in 2000, ABC TV did an expose on child labor and terribly low wages on Guatemalan plantations. After it aired, Global Exchanged petitioned Starbucks stockholders at an annual meeting in Seattle. That week, Starbucks announced that they would make an one-time order of 75,000 pounds of Fair Trade coffee. Thinking that it was not enough, Global Exchange presented a letter signed by eighty four organizations asking Starbucks to use Fair Trade coffee and planned thirty demonstrations for 13 April, 2000 at various Starbucks locations. Three days before the demonstrations, Starbucks announced to TransFairUSA that they would offer Fair Trade Certified coffee in all of its locations.[18] The key to Starbucks' success has been its adaptation to consumer demands, and introducing fair trade coffee is an example of how the company has capitalized on consumer trends.

History of Starbucks

The history of Starbucks is one that is well documented. At first the simple company was started with a few friends that had a love for coffee: Jerry Baldwin, Gordon Bowker and Zev Siegl. However, the Starbucks brand started from a vision that Howard Schultz had as the marketing and operational manager of Starbucks in 1982. He envisioned coffee as he witnessed it in Italy; this vision came to him while he was on a business trip in Milan. Because of this vision, Schultz launched a rollercoaster ride that took a small Seattle company to the multi-billion dollar apex of the coffe industry it is today. From the start, he wanted to recreate the Milan coffeehouses in the United States, exploit consumer trends in coffee consumption, make a logo that could be world renowned and to reinvent Starbucks coffee as an ethically responsible company.

Schultz's idea was to copy what he saw in Milan espresso bars and to recreate an environment that would produce the same results as a hospitable and comfortable environment for the enjoyment of coffee in the United States.

"Coffeehouses in Italy are a third place for people, after home and work. There's a relationship of trust and confidence in that environment." -Schultz

He had become a general manager for a Swedish drip coffee maker manufacturer Hammerplast in 1979; in a business trip to Seattle, he visited Starbucks, then a relatively popular local cafe chain. In 1982 he then joined Starbucks as the Director of Marketing. During a trip to Milan, he noted the existence of coffee bars on every street, which served not only coffee but the space as meeting grounds for people. Upon his return to Seattle, he tried to persuade the owners of Starbucks to try a new coffeehouse concept which included espresso, but was unsuccessful. Carrying frustration, Schultz opened his own coffeehouse called Il Giornale in 1985. In 1987, the original Starbucks management decided to focus on another venture, thus selling the Starbucks company to Schultz for $3.8 million. After purchasing the brand, Schultz joined his coffee ventures and named it Starbucks, serving coffee and espresso much under the influence of his cafe experiences in Milan.

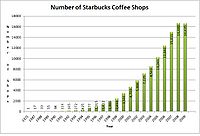

However, the rise of Starbucks did not come about without looking at the trends and the statistics of the time. Jospe L. Rotman School of Management reports that there were "four underlying issues" that were happening in the 1990s that produced the rise of coffee drinkers. One, people were seeking healthy alternatives to alcohol. Secondly, people (particularly youth) were in need of a place to socialize in places other than bars and clubs. Third, coffee was seen as what Rotman calls "an inexpensive luxury". Four, people were becoming aware of coffee based drinks such as lattes and realizing that gourmet coffee could be enjoyed as something more than an energy boost. The coffee culture of the Araabian peninsula and the London coffeehouse was being reborn. As tea had replaced coffee consumption in England before large scale emigration took place to North America, coffee's niche in North America was a beverage to refresh mental concentration, not as a social tool. All Business' website reports that in 1990, about 52% of the population drank coffee with the majority being adults over the age of thirty. The increase of European-style coffee consumption in North America can be seen in the sheer amount of coffee importation to the United States in 2009, at 23 million bags of coffee imported. (Coffee consumption historical data) The entrepreneurial mind of Schultz is in large part responsible for this expansion; sensitive to consumer demand for an alternative to alcohol and increased disposable income among teens, he created a brand that would be marketed as what coffee has always been as its essence - the symbol of social exchange.

The Starbucks brand has come a long way from a small Seattle company to a multi-billion dollar corporation. A simple cup of coffee has come to be seen as a sophisticated trend. Starbucks is world renowned today, placing on the highest of market levels along with other major corporations like Nike and Coca-Cola. The impact that Starbucks has had on the world is immense, with a franchise store found literally on every other street corner and few are ever quiet.

References

- ↑ Brooks, C. "Coffee Cultivation and Exchange 1400 - 1800." University of Santa Cruz, n.d. <http://people.ucsc.edu/~cbrooks/coffee/1400-1800.html>

- ↑ Thruber, Francis. Coffee from Plantation to Cup. 6th ed. New York: American Grocer Publishing Corporation, 347. 1884. eBook.

- ↑ Ios Research Network. "The Bazaar in the Islamic World." Ios Minaret 16 Aug 2007: n. pag. <http://www.iosminaret.org/vol-2/issue8/bazaar_Islamic_World.php>

- ↑ Ios Research Network

- ↑ Seidl, Dave. "coffee - the Wine of Islam." Superluminal, 1999. <http://www.superluminal.com/cookbook/essay_coffee.html>

- ↑ Clark, Taylor. Starbucked: a Double Tall Tale of Caffeine, Commerce and Culture. NY: Little, Brown. 2007.

- ↑ Clark, 26

- ↑ Clark, 25

- ↑ Clark, 28

- ↑ Gervase, 8

- ↑ Berryman, Phillip. "The Cost of Coffee." Environment 19.6 (1977), 14.

- ↑ Laslett, Michael. "A Bitter Taste." NACLA Report on the Americas 34.6 (2001). 10.

- ↑ James, Deborah. "Justice and Java: Coffee in a Fair Trade Market." NACLA Report on the Americas 34.2 (2000). 11.

- ↑ James, 11

- ↑ James, 13

- ↑ Global Exchange website

- ↑ James, 14

- ↑ James, 14

Other Works Cited

- CoffeeResearch Organization. Market. 2006. <http://www.coffeeresearch.org/market/usa.htm>

- International Coffee Organization. Importing Members. <http://www.ico.org/historical/2000+/pdf/importsimcalyr.pdf>

- International Coffee Organization. Importing Members. <http://www.ico.org/historical/2000+/pdf/consumption.pdf>

- Joseph L. Rotman School of Management. "The Starbucks Brand". <http://www.rotman.utoronto.ca/bic/case%20series/pdfs/starbucks.pdf>

- Mullins, John. "Howard Schultz and the Coffee Experience". August 2007. <http://www.venturenavigator.co.uk/content/159>

- Starbucks. "A Brief History of Starbucks" 2005. <http://www.starbucks.ca/en-ca/_about+starbucks/history.htm>

- Tea & Coffee Trade Journal. "1990 US Winter Coffee Drinking Survey" 1 May, 1990. <http://www.allbusiness.com/manufacturing/food-manufacturing-food-coffee-tea/162933-1.html>

- Thompson, Arthur A., John E. Gamble. Starbucks Case Study. 1997. <http://www.mhhe.com/business/management/thompson/11e/case/starbucks-2.html>