Course:FNH200/2011w Team19 StoutBeer

Stout is a type of specialty beer originating from 18th century Europe. It was favoured by British workers and porters, and was originally labelled as porters after its consumers[1]. The word stout also means strong, and the term was originally used to classify alcoholic content in beverages. In the early 19th century, the Guinness brewery began to specifically produce stout porters, which eventually became their flagship beverage[1].

Stout beer is brewed with roasted malt or barley[2], and is characterized by its bitter taste and strong colour[3]. Guinness is often considered the most famous producer of stout beer[4]. Stout is smoother than other beers due to its lack of carbonation, and does not produce the stinging sensation when consumed[4]. Although this page will mainly focus on the brand Guinness as a case study, for clarity, the information presented also applies to the greater category of stout beer made by other manufacturers.

Production and Processing

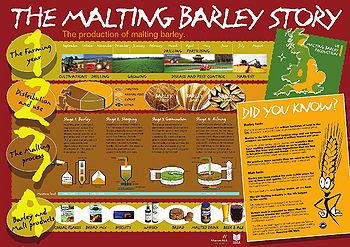

Stout production can be divided into 7 major steps: malting, milling, mashing, separation, brewing, fermentation, and maturation[2]. Malting refers to the conversion of barley into malt: barley is immersed in water, instigating sprouting, but controlled by drying to discontinue the growth when optimum levels have been achieved. Milling is the grinding of malt into grist, then, the sugars of the grist are brought out by mashing; the mixing of grist with hot water. Separation removes the larger particles and solids out of the brewed water called the “wort.” Boiling is the sterilization of the wort, converting it into an extremely concentrated form. Fermentation is accomplished by adding yeast to the wort to convert sugars to alcohol and carbon dioxide. Maturation refers to a length of time that the beer is stored to achieve its distinctive flavor[2].

Malting

Malting involves steeping, germination, and kilning of raw barley to convert it into what is known as malt. Steeping activates the enzymes in the barley to begin sprouting[2]. The barley is then steeped in cool water for about 48 hours, with dry breaks in between called air rests. Just before a new plant is formed from sprouting, the grain is kilned with heat to dry out the malt[2]. This process also preserves the malt, as the enzymes are unable to function without sufficient water activity [5].

Milling

The milling process reduces the size of the grain while keeping the outer husk intact, to be used later during the brewing process. The malt is crushed to release the inner starch while preserving the outer husk. Depending on what type of milling or to what extent the grain is compressed, the characteristics of the beer will be affected.[2]

Mashing

Mashing contributes to the distinctive taste of a specific beer, as it modifies the sugar and alcohol levels of the final product[2]. Mashing involves mixing the compressed malt with hot water and continuously heating it to a boiling point, allowing the malt enzymes to convert grains into fermentable sugars, and produces the liquid extract known as wort. The separation of small grain residues can occur in the same vessel, called a mash tun. The mash tun has a small opening at the bottom that allows the wort to flow through straining tubes and leave the grains behind[2].

Boiling and Fermentation

After mashing, the wort enters a brewhouse or brewery for boiling. Hops are added at the beginning of the boil to achieve the signature bitterness of all stout beers. The boil eliminates all the undesirable bacteria and moulds, while extracting flavor from the barley. Boiling also brings out the unique colour of the beer by concentrating the sugars and evaporating water[2].

After boiling the wort, it is cooled to a predetermined temperature for fermentation, which is around 8 to 20°C[2]. The specific temperature of fermentation depends on the strain of yeast used[6]. It is essential to cool the wort rapidly to prevent any uncontrollable color changes and to avoid contamination[2]. Metal plates are utilized for their high heat conductivity[2]. The wort is put into a chamber with metal plates chilled with cold water[2]. After the wort reaches optimal temperature, yeast is added to start the fermentation of sugar molecules into alcohol[2]. An aerobic environment is provided for the yeast to convert pyruvate into ethanol and carbon dioxide[2]. The fermentation process is approximately six days in duration[6]. Towards the end of the procedure, most of the sugars have converted into alcohol[2].

Maturation and Beyond

After fermentation, the beer is matured in beer barrels[2]. Maturation clears the liquid and helps to develop flavour and aroma[2]. During maturation, the beer needs to be held at a low temperature (e.g. 3°C) for approximately 14 days[6]. At the end of maturation, the beer embodies the full characteristics of stout, but it is not yet ready to be consumed. Filtration, bottling or canning, and pasteurization are the steps to follow. A pore filtration method is usually used for stout[6], whereas other beers may use cold filtration, a type of sterile filtration[5]. When pore filtration is used, pasteurization must follow bottling or canning, because pore filtration does not eliminate all spoilage and disease causing microorganisms that could affect consumers[5]. The pasteurization process usually takes place at 60°C for 15 minutes[6]. During the pasteurization process, intrinsic flavouring agents of stout may degrade, thus improvements have been made to develop an appropriate sterile filtration and packaging method to preserve as much flavour as possible[7].

To learn more about specific ways different brands of stout are brewed, check out the step-by-step brewing processes at the websites of Guinness and Murphy's.

Packaging

The functions of packaging are multi-faceted. These include: the protection of the product, a barrier between the product to reduce the risk of contamination, agglomeration or the groupings of multiple products in one package to increase transport and handling efficiency, convenience, and information transmission/marketing[8].

According to the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA), there are many regulations that beer manufacturers must follow in regards to information that must be incorporated on their labels. Material that must be provided includes: common name of the product, net quantity, alcohol content by volume, and name and address of the dealer[9]. As stout beer is a standardized alcoholic beverage, meaning it has compositional standards set out by the Food and Drug Regulations (FDR), it does not require an ingredient list.

The beer must be protected because beer is a foodstuff. "As with most foodstuffs, beer is perishable-it deteriorates as a result of the action of bacteria, light, and air”[10]. The packaging choice of the beer company can help minimize these effects, such as the popular usage of aluminum cans, which are tightly sealed, and bottles which have specialty caps to keep oxygen out[11].

Light exposure, or photodegradation, causes the MBT (3-Methyl-2-Butene-1-Thiol) in beer to create a “skunky” flavour. Hops, and ingredient in beer that causes the bitter flavour characteristic of some stouts, “contai[n] compounds called isohumulones that degrade with light, break down into free radicals, and react with sulfur-containing compounds.” These reactions can be slowed with proper packaging choices, such as packaging the beer in cans, dark bottles (usually amber or green), or using opaque secondary packaging.

Will PET plastic (polyethylene terephthalate) packaging be used for beer in the future? The benefits of plastic packaging would include increased recyclability, lighter weight, and the ability to form PET into unique shapes (without a cost increase!). The negative effect of PET would be the shortness of shelf life of the beer, as plastic is more porous than glass or aluminum. However, PET can be mono- or multi-layered in order to fit specific company’s needs for their unique formula[12].

Widget

A widget is plastic ball punctured to release pressurized nitrogen into the can of beer when opened. The nitrogen compensates for the lack of carbon dioxide in stout beer, without which the beer would produce less head, the foam at the top of the beverage. Nitrogen released from the widget produces the creamy head associated with stouts, while the lack of carbon dioxide prevents the sharp, stinging taste associated with other beers. The creamier head is due to the bubbles formed by nitrogen being smaller than bubbles formed by carbon dioxide. Since nitrogen gas does not readily dissolve in stout beer, the need of the widget becomes apparent. By opening the can of beer, loss of internal pressure forces the nitrogen gas within the widget into the beverage to form the head[13].

The cost of manufacturing and implanting widgets in cans significantly increases the overall cost of the stout. The widget must be sterilized (deoxygenated) to prevent growth of microorganisms inside the can during storage[14].

Recently, Irish scientists have discovered that plant cellulose fibers, in a concentrated pad a few centimeters across, can nucleate bubbles. Cellulose fibers are responsible for the formation of bubbles in carbonated beers as well, however, the bubbles form approximately twenty times faster with carbon dioxide than nitrogen. With a pad similar to a coffee filter, the amount of nitrogen exposed to cellulose is dramatically increased, and thus a creamy head can form at a speed comparable to other beers. This pad is cheaper to manufacture, easier to incorporate into the production process, and more environmentally friendly. Many stout brewers have already adapted it, and with it, the cost of stout should soon fall[13].

Even with the help of the widget or the cellulose fiber pad, pouring a perfect pint of stout is still an art that needs a few tips. Although the following video demonstrates how to pour stout from a tap, the same tips apply to pouring stout out of a can or bottle:

Regulations

The Canadian Brewery Industry

The Canadian Brewery Industry is the largest industry of the alcohol beverage sector, producing a wide variety of beers including lager, ale, stout, and draught. According to the North American Industry Classification System principal statistics (NAICS), in 2007, the value of exports produced by the brewery industry totalled $327 million while imports totalled $548 million[15]. The industry is regulated by a complex framework to ensure the safety and quality of their products to consumers. Various regulatory agencies include the Canadian Wheat Board (CWB), Provincial and Territorial Liquor Boards and the Agreement on Internal Trade (AIT). However, it is the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) that regulates and sets the standard for food manufacturing, production, and labelling[15].

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency

Under the Food and Drug Regulations B.02.130/B.02.131, the CFIA has regulated the standards of beer, ale, stout, porter and malt liquor:

- It shall be the product of an alcoholic fermentation by yeast of an infusion of barley or wheat malt and hops or hops extract in potable water[16].

- It may be added with, during manufacturing, ingredients such as cereal grain, salt, carbohydrate matter, carbon dioxide, dextrin, food enzymes and stabilizing agents, etc [16]. Check out the complete list of acceptable ingredients online at the Food and Drug Regulations web page regarding beer.

Ireland’s Brewing Sector

Ireland’s beer industry is regulated by the European Union (EU) and the Food Safety Authority of Ireland (FSAI). These bodies determine the standards for alcoholic beverages, including food legislation for additives, production, and specific labelling requirements.

The FSAI regulates food production in the State, food marketed or distributed in the State, and any legislated food safety and hygiene standards[17]. Under the Council Regulation (EC) No 834/2007 Act, agricultural products either processed or unprocessed intended for human consumption and yeast are subject to production rules[18]. This indicates that all forms of genetically modified organisms are prohibited as well as treatment by ionizing radiation[18].

Along with ingredient regulations, there are also packaging and labelling requirements. Under the Commission Directive 87/250/EEC, the labelling of alcoholic beverages containing more than 1.2% by volume must indicate the alcoholic strength by volume showing the word “alcohol” or the abbreviation “alc” followed by the "% vol."[19]. Alcohol strength shall be determined at 20°C. For imported beer, products must include name of importer, local administrative area preceded by the word(s) “imported by” as well as allergenic ingredients[19].

Interestingly, both brewing industries contribute largely to their national economy through both exports and imports of various beer products. In 2009, the Irish brewing industry generated €200 million (approximately $260 million USD) in exports [20], which is quite comparable to the Canadian brewing sector.

Sensory Aspects

Sensory perception of stout beer is an important determinant in consumer choice. Besides flavour, appearance, and mouthfeel, individuals may also perceive orosensation of stout differently due to psychological and genetic differences [7]. Nonetheless, most brewers want to keep the image of beer as a natural product, so additives, including preservatives and colors, are added with restraint[7].

Flavour

The flavour of stout beer is composed of a bitter taste laced with sweetness and a "hoppy" aroma. The bitter taste is mainly caused by isoalpha acids, the precursor of which is alpha acids, present in the lupulin glands of flowers on female hop plants ("Humulus lupulus")[21]. Surprisingly, alpha acids are not bitter: but after heating in a kettle, isomerization takes place. The resulting product, isoalpha acids, are bitter[22]. Thus, longer boiling time of wort results in more isoalpha acids that contribute to a more bitter taste.

The hint of sweet taste in stout is associated with carbonyls (e.g. 3-methylbutanal and i-butanal)[23]. The source of these compounds is dark malt, released during kilning[23].

The lupulin glands also contain hop oils, which are responsible for the "hoppy" aroma[21]. Because hop oils are evaporated or thermally degraded during wort boiling, hop dosage at the end of wort boiling is used to ensure the amount of aromatic compounds in the final product[21]. An alternative to hop has also been identified: "bitter leaf" (Vernonia amygdalina), a plant native to Nigeria[24].

Instead of additives, brewers influence flavour by controlling the raw materials, the fermentation conditions and packaging techniques. Some examples of the raw materials that have effects on the flavour of stout are yeast strains, hop varieties and mineral content of water[7]. Changing conditions for each of the stages discussed in the section of Production and Processing of Stout can change the flavour significantly. Similarly, packaging techniques such as aseptic filling and use of different pasteurization systems also influence the flavour by controlling the amount of oxidants in the stout[7]. By lowering the oxygen content in the wort, flavour stability of stout was shown to be improved[25].

An example of altering stout flavour by changing the raw materials is creating new hop and barley varieties from cross-breeding of existing cultivars of the plants, i.e. biotechnology. However, the process is not easy, and viable new cultivars are the result of many years of breeding program and progeny testing[7].

Appearance

The dark colour of stout beer is achieved by colored Maillard compounds (melanoidins) and caramelization products, both of which are produced by heating carbohydrates and proteins[3]. These compounds are released during malt roasting and wort boiling[26]. In addition, the color of stout can be darkened further by adding caramel color (class III; E150C), which is also a source of Maillard compounds and caramelization products[27].

Mouthfeel

Other than flavour and appearance, mouthfeel also contributes significantly to consumer sensory perception of stout beer. The mouthfeel of stout includes temperature, fullness and carbonation. It is no coincidence that all stout packages advise consumers to "serve extra cold." The coolness of chilled stout is proven to better quench thirst than un-chilled stout, and thus consumers prefer to drink chilled stout[4]. In a study that compares the mouthfeel elicited by seven types of beer including stout (Guinness Extra Draught stout as the representative stout sample), stout was consistently rated lowest on carbonation but highest in fullness[4]. Fullness depends on density and viscosity of the stout, whereas the carbonation depends on sting, bubble size, foam volume and total carbon dioxide[28]. The low carbonation of stout gives rise to the smooth sensation of the beer in mouth. In fact, Guinness has made a commercial to show just how "smooth" the stout is:

Variety

Dry Stout

Modern stout beers come in many different varieties. When the word "stout" is used, however, it is usually referring to the famous Guinness beer, which is a dry stout. The Guinness breweries labeled their dark porters with Single Stout and Double Stout to differentiate their strength, but eventually their popular beverage became known simply as "stout."

Guinness was not only one of the largest overall brewers in Ireland, they had also pioneered many quality control methods. In 1899, the brewery hired statistician William Sealy Gosset as a quality control expert[29]. Due to previous employees publishing academic literature, which disclosed the brewery's trade secrets, the company mandated that all employees must adopt a pseudonym to prevent competitors from tracing publishing back to the brewery[29]. Gosset adopted the pseudonym "Student"[29], and went on to author the Student's t-distribution and the Student's t-test while working for the brewery[30][29]. The t-distribution is a derivative of the normal distribution, with which one can estimate the mean of a population when the sample size is extremely small, and the standard deviation of the population is unknown[31]. This worked particularily well for the Guinness brewery, as they can only provide very limited information during the production process and barley harvest to be analyzed for quality control and yield optimization[29]. Both the Student's t-distribution and the Student's t-test had become fundamental statistical principles still in use today.

Other Available Flavours

There are many other available specialty flavours of stout that have received much attention, such as "oatmeal stout, milk stout, imperial stout, bourbon barrel-aged stout, cherry stout, chocolate stout, coffee stout and oyster stout"[32].

Trivia

- American brewers annually produce more than 66 billion 12-oz servings of malt beverages, including beers, ales, lagers, and stouts [7].

- The lupulin glands also contain another group of compounds that have proven to inhibit aromatase activity in humans, which results in lowered estrogen levels[33]. This finding relates hop-containing beer, such as stout, to breast cancer prevention[33].

Summary

Stout is relatively new with respect to beer types, despite being nearly three hundred years old (Guinness was established in 1759, making this brand alone 253 years old as of 2012)[34]. Stout is a dark, heavy beer, and is in fact so thick and filling that it has been long since referred to as "a meal in a cup"[35]. While stout is produced in a manner similar to other beers, the nitrogen content of stout separates it from other beer, and has led to a unique packaging process that incorporates a widget that releases pressurized nitrogen. The enduring popularity of stout beers has led to brands like Guinness becoming one of the most successful brewing companies worldwide.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Jackson, M. 1998. Porter Casts a Long Shadow on Ale History. Retrieved 13 Mar 2012.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 Priest, F.G., & Stewart, G.G. 2006. Handbook of Brewing. Second Edition. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Coghe, S., Adriaenssens, B., Leonard, S., & Delvaux, F.F. 2004. Fractionation of Colored Maillard Reaction Products From Dark Specialty Malts. Journal of American Society of Brewing Chemists 62:79-86.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Pickering, G.J., Bartolini, J-A., & Bajec, M.R. 2010. Perception of Beer Flavour Associates with Thermal Taster Status. Journal of the Institute of Brewing and Distilling 116: 239-244.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Beadle, L.P. 1973. Brew It Yourself: A Complete Guide to the Brewing of Beer, Ale, Stout and Mead. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux Press.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Biendl, M., Methner, F.J., Stettner, G., & Walker, C.J. 2004. Brewing Trials with a Xanthohumol-Enriched Hop Product. Brauwelt International 3:182-184.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 Hermelstein, N.H. 1998. Beer and Wine Making. Food Technology 52: 84-90.

- ↑ Louw, A. & Kimber, M. 2012. The Customer Equity Company. Retrieved 12 Mar 2012.

- ↑ Canadian Food Inspection Agency. 2011. Ch. 10: Labelling of Alcoholic Beverages. Retrieved 01 Mar 2012.

- ↑ Beverage Tasting Institute. 2012.Beer is a Perishable Product Retrieved 12 Mar 2012.

- ↑ Food Science Secrets. 2012. Wassup with Beer? Retrieved 12 Mar 2012.

- ↑ Packaging Gateway. 2004. PET: The Shape of Things to Come Retrieved 12 Mar 2012.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Devereux, M.G. & Lee, W.T. 2011. Mathematical Modelling of Bubble Nucleation in Stout Beer and Experimental Verification. Proceedings of the World Congress on Engineering.

- ↑ Lee, W.T. & Devereux, M.G. 2011. Foaming in Stout Beers. American Journal of Physics 79:991-998.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. 2011. The Canadian Brewery Industry. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Department of Justice of Canada. 2012. Food and Drug Regulations C.R.C., c. 870. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- ↑ Food Safety Authority of Ireland. 2001. Guidance Note on the EU Classification of Food. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Food Safety Authority of Ireland. 2009. Legislation. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Europa Summaries of EU Legislation. 2011. Alcoholic strength by volume ‘% vol.’. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- ↑ Alcohol Beverage Federation of Ireland. n.d. The Irish Beer Industry and its Importance to the Irish Economy. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Wunderlich, S., Zurcher, A., & Back, W. 2005. Enrichment of Xanthohumol in the Brewing Process. Molecular Nutrition and Food Research 49:874-881.

- ↑ Fritsch, A., & Shellhammer, T. 2007. Alpha-acids Do Not Contribute Bitterness to Lager Beer. Journal of the American Brewing Chemists 65:26-28.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Foster, C., Narziss, L., & Back, W. 1998. Investigations of Flavor and Flavor Stability of Dark Beers Brewed with Different Kinds of Special Malts. Convention of the Master Brewers Association of the Americas 35:91-107.

- ↑ Lasekan, O.O., Lasekan, W.O., & Babalola, J.O. 1998. Effect of Vernonia Amygdalina (Bitter Leaf) Extract on Brewing Qualities and Amino Acid Profiles of Stout Drinks From Sorghum and Barley Malts. Food Chemistry 64:507-510.

- ↑ Unichida, M., & Ono, M. 2000. Technological Approach to Improve Beer Flavour Stability: Analysis of the Effects of Brewing Processes on Beer Flavour Stability by the Electron Spin Resonance Method. Journal of the American Society of Brewing Chemists 58:8-13.

- ↑ Noddekaer, T.V., & Andersen, M.L. 2007. Effects of Maillard and Caramelization Products on Oxidative Reactions in Lager Beer. Journal of the American Society of Brewing Chemists 65:15-20.

- ↑ Kamuf, W., Nixon, A., Parker, O., & Barnum, G.C., Jr. 2003. Overview of Caramel Colors. Cereal Foods World 48:64-69.

- ↑ Langstaff, S.A., Guinard, J-X., & Lewis, M.J. 1991. Sensory Evaluation of the Mouthfeel of Beer. Journal of the American Society of Brewing Chemists 49:54-59.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 Hotelling, H. 1930. British Statistics and Statisticians Today. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 25:186–190.

- ↑ Fisher, R.A. 1926. Review of Statistical Methods for Research Workers. Eugenics Review 18: 148–150.

- ↑ Gosset, W.S. 1908. Probable Error of a Correlation Coefficient. Biometrika 6: 302–310.

- ↑ Jensen, D. 2011. All About Stout.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Monteiro, R., Becker, H., Azevedo, I., & Calhau, C. 2006. Effect of Hop (Humulus lupulus L.) Flavonoids on Aromatase (Estrogen Synthase) Activity. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 54:2938-2943.

- ↑ Guinness. 2009. The Story of the Beer Retrieved 22 Mar 2012.

- ↑ What is Guinness? 2012. Food Reference - A Meal in a Cup Retrieved 22 Mar 2012.