Course:FNH200/2011w Team08 Sourdough

Sourdough Bread

History of Sourdough Bread

Sourdough bread is leavening bread with a sour tang taste. Although there is no documentation on the first discovery of sourdough bread, it is thought to be one of the oldest foods known to man and was discovered completely by accident with a piece of dough from the previous baking, which soured and rose while the dough was stored.[2]

First made as early as 3000 BC by the Egyptians, lactic acid bacteria and yeast cause the leavening of the bread when left to rise, creating the characteristic puffiness and flavour that distinguishes leavening and flat breads.[3] Due to the fact that ovens did not come until much later, the bread was still fairly flat but had different flavour characteristics. [4]

By the Middle Ages commercial bakeries had tamed and collected various yeasts and it was soon after realized that it was first created by beer brewers yeast. [5] Although, it is a specific strain of wild yeast, called Lactobacillus, which creates the unique taste. Unlike regular yeast, the yeast found in sourdough cannot metabolize maltose and thrives only in an acidic environment, resulting in a sour tang taste. [6]

This process continues to be used to improve aroma, crust, and also to extend the shelf life. [7]

The Science of Sourdough

The characteristic flavour, texture and aroma of sourdough bread is due to the action of bacteria and yeast. These microorganisms oxidize organic compounds in the dough to generate energy through the process of fermentation.[8]

Lactic Acid Bacteria and Yeast

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) produce lactic acid, which decreases the pH of the dough. Yeast plays a part in the production of flavour compounds.[9] LAB require yeast, unsaturated fatty acids and maltose or glucose to grow. The yeast is important to the survival of LAB as the amino acids they produce stimulate its growth. The LAB consume maltose and produce lactic acid, carbon dioxide and glucose. The yeast uses the glucose produced by the LAB and makes carbon dioxide as a product of their metabolism. To function properly the yeast must be able to survive in the acidic environment (pH=3.5), created through the production of lactic acid by the LAB. Saccharomyces exiguus is a yeast commonly used in sourdough starters because of its ability to function in acidic conditions. Baker's yeast or Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which is commonly used in other breads, cannot tolerate the acidic conditions created by the LAB and is not usually found in sourdough cultures. [10]

Interesting fact: The lactic acid bacteria that is responsible for the famous San Francisco sourdough is unique to that area and is called Lactobacillus sanfrancisco[11]

Making a Sourdough Culture

To produce sourdough bread, a sourdough culture must be made. A sourdough culture consists of[12]:

- Water

- Flour

- Lactic acid producing bacteria

- Yeast if it is present in the environment.

Spontaneous fermentation: naturally occurring bacteria are present in the flour, which produce lactic acid and lowers the pH of the dough. This process occurs spontaneously when flour and water are left out at room temperature for one to two days. In these cultures lactic acid bacteria present is 3x109 colony forming units (CFU) per gram and the amount of yeast produced is around 106 CFU/gram[13]. Using this method can be risky as it can potentially produce a product with an undesirable flavour[14].

Cultures that begin by spontaneous fermentation but have been kept active for many years through the addition of flour and water each day are called mature sourdough. The process of adding water and flour to an existing culture is called freshening[15].

Mixing a pure culture of lactic acid bacteria and yeast with flour and water makes a starter culture. The mixture is left untouched for a couple hours allowing fermentation and multiplication of microorganism to occur[16].

Types of Sourdough Starters

There are three types of sourdough starters, type I, type II and type III.

- Type I: This is the traditional form in which flour and water are added daily to keep the microorganisms active. The lactic acid bacteria and yeast are naturally found in the air and the flour and multiply within the flour and water mixture[17].

- Type II: A semi-fluid preparation that is added to dough to acidify it. These preparations are made by a fermentation process that is carried on for 2-5 days at temperatures above 30°C. They are often used in industrial sourdough production as they give rise to an acidic product in a short amount of time.[18]

- Type III: A starter culture that is dehydrated through spray drying. It is used to acidify the dough and as a carrier of aroma. Because it has been dehydrated this culture can be stored for extended amounts of time[19].

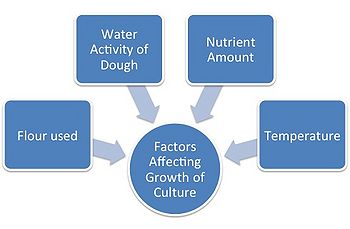

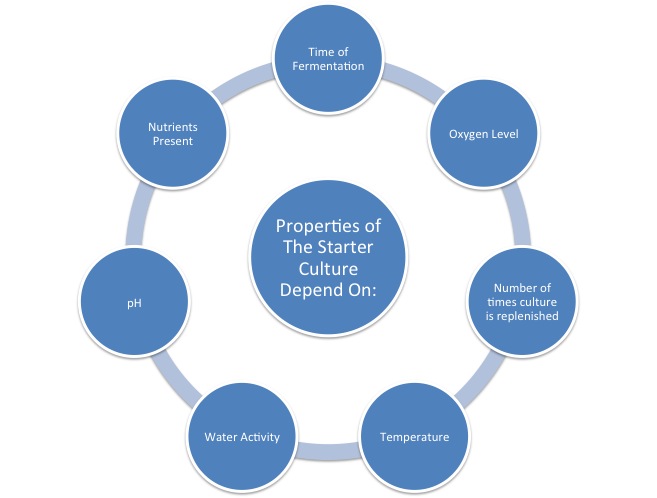

Factors Determining Outcome of Starter Culture

The properties of the starter culture depend on 7 factors[20]. These factors all affect the microorganisms that are present in the culture[21].

The Baking Process

To create the final dough mixture, the starter culture is combined with the other ingredients and optional flavourings.[22] The proportion of starter culture within the final dough may vary, but is usually not less than 30%. [23] After being kneaded, the dough is then left to ferment for up to 12 hours [24]; during this time the accumulation of lactic acid contributes acidity, and the carbon dioxide causes the dough to rise.[22] In order to speed up the process, baker’s yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) may be used to reduce the leavening time to about 1 to 1.5 hours. [24]

The following is a simple recipe using baker’s yeast (modified from Wood, 1996 [25]; cited in Wagner, 2005 [24]):

- 1. Combine the following:

- 1 cup starter culture

Kneading the dough [26] - 4 g baker’s yeast

- 9 g warm butter

- 9 g salt

- 600 g flour

- 1 cup milk

- 26 g sugar

- 1 cup starter culture

- 2. Knead the dough.

- 3. Place the dough in a greased pan and let rise for approximately 1 hour.

- 4. Bake at 350˚F for 30-45 minutes.

- 1. Combine the following:

The final product should be golden brown and should sound hollow when tapped underneath. [27] The bread must be left to cool for at least 45 minutes before slicing. [27]

Properties of Sourdough Bread

Flavour, Texture and Shelf Life

The flavour of sourdough bread can differ depending on the starter culture used. Some of the yeast found in the starter culture has been active for long periods of time, and the age of the culture gives the sourdough bread its unique and distinct taste. Some people use instant yeast as a replacement for the yeast naturally present in the starter culture. This creates a bread with a flavour close to that produced with the original method, but it defeats the purpose of making sourdough bread without buying, and storing commercially bought yeast.[28] The taste originates from the lactic and acetic acid found in the bread. These acids are produced by the bacteria Lactobacili, giving the bread its unique tangy and sour flavour and aroma.

The long shelf life of sourdough bread is due to the high water binding capacity of the flour particles, resulting in lower crumb firmness and decreased water activity, which prevents microbial growth. The lactic acid is responsible for the water binding property of the bread as it causes starch granules to swell, slowing down water loss and staleing. The bacteria, Lactobacilius plantarum prevents the growth of mould spoilage microorganisms. Due to these properties, the storage life of the sourdough bread is much longer than standard bread. [29]

How is Sourdough Different From Other Breads?

The function and use of yeast in sourdough bread is the main cause for its variation amongst other risen breads. Today, most bakers use store bought cultivated yeast (occasionally called dry active yeast).[30]

This yeast is granulated to form tiny yeast particles which are then dried and vacuum sealed. While the yeast remains dormant in the package, it can successfully be activated to produce a leavened bread or bread product [31]. Its activation is typically carried out through the addition of water which re-activates the yeast fungi that feed on the sugar and starch to make the bread rise [32]. Sourdough bread however deals with yeast in a completely unique manner. Unlike other yeast based breads, the sourdough yeast fungi are actually kept alive in a liquid medium called a starter [33]. In addition, the eating habits of the yeast in sourdoughs and other raised breads differ from one another. The predominant yeast in sourdough, Saccharomyces exiguus, cannot metabolize one of the sugars that is present in the flour; maltose. However, Baker’s yeast, can easily feed on this sugar. Since the bacteria that give sourdough bread its taste is dependent on maltose to function and reproduce, they thrive much better in the company of sourdoughs yeast where they don’t have to compete with this sugar [34].

Packaging of Sourdough Bread

One desirable property of Sourdough Bread which the consumer looks for upon purchase is a crispy crust. To be able to successfully reach this property, Sourdough Bread is often packaged in a brown paper bags with one end exposed to the surrounding environment. The exposure to the surrounding environment, allows the bread to gradually lose its moisture and form the desirable crispy crust. On the contrary, bread that is packaged in plastic bags, with both ends sealed is able to retain it's moisture which leads to the formation of a product with a tough and chewy crust. [36]

References

- ↑ Hasan, Beni. (2010). Woman Grinding Grain. retrieved from http://teachmiddleeast.lib.uchicago.edu/historical-perspectives/the-question-of-identity/before-islam-egypt/image-resource-bank/image-13.html

- ↑ Hansen, A. and P. Schielberle. (2005). Generation of Aroma Compounds During Sourdough Fermentation: Applied and Fundamental Aspects. Trends in Food Science and Technology. Vol. 16, Iss. 1-3. pp. 85-94.

- ↑ Hansen, A. and P. Schielberle. (2005). Generation of Aroma Compounds During Sourdough Fermentation: Applied and Fundamental Aspects. Trends in Food Science and Technology. Vol. 16, Iss. 1-3. pp. 85-94.

- ↑ Mariani, J. (1997). Sourdough bread. Restaurant Hospitality, 81(7), 86-86.

- ↑ Mariani, J. (1997). Sourdough bread. Restaurant Hospitality, 81(7), 86-86.

- ↑ Hansen, A. and P. Schielberle. (2005). Generation of Aroma Compounds During Sourdough Fermentation: Applied and Fundamental Aspects. Trends in Food Science and Technology. Vol. 16, Iss. 1-3. pp. 85-94.

- ↑ Hansen, A. and P. Schielberle. (2005). Generation of Aroma Compounds During Sourdough Fermentation: Applied and Fundamental Aspects. Trends in Food Science and Technology. Vol. 16, Iss. 1-3. pp. 85-94.

- ↑ Jespersen, L., Josephsen, J. (2004). Starter cultures and fermented products. In Handbook of food and beverage fermentation technology. CRC Press.

- ↑ Meignen, B., Onno, B., Gelinas, P., Infantes, M., Guilois, S., Cahagnier, B. (2001). Optimization of sourdough fermentation with Lactobacillus brevis and baker’s yeast. Food Microbiology, 18, 239-245.

- ↑ Gobbetti, M., Corsetti, A. (1997). Lactobacillus sanfrancisco a key sourdough lactic acid bacterium: a review. Food Microbiology, 14, 175-187.

- ↑ Gobbetti, M., Corsetti, A. (1997). Lactobacillus sanfrancisco a key sourdough lactic acid bacterium: a review. Food Microbiology, 14, 175-187.

- ↑ Vuyst, L., Neysens, P. (2005). The sourdough microflora: biodiversity and metabolic interactions. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 16, 43-56.

- ↑ Hansen, A.S. (2004). Sourdough bread. In Handbook of food and beverage fermentation technology. CRC Press.

- ↑ Hansen, A.S. (2004). Sourdough bread. In Handbook of food and beverage fermentation technology. CRC Press.

- ↑ Hansen, A.S. (2004). Sourdough bread. In Handbook of food and beverage fermentation technology. CRC Press.

- ↑ Hansen, A.S. (2004). Sourdough bread. In Handbook of food and beverage fermentation technology. CRC Press.

- ↑ Corsetti, A., Settanni, L. (2007). Lactobacilli in sourdough fermentation. Food Research International, 40, 539-558.

- ↑ Vuyst, L., Neysens, P. (2005). The sourdough microflora: biodiversity and metabolic interactions. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 16, 43-56.

- ↑ Vuyst, L., Neysens, P. (2005). The sourdough microflora: biodiversity and metabolic interactions. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 16, 43-56.

- ↑ The Fresh Loaf. (2005). Outline of the sourdough process. Retrieved March 3, 2012, from http://www.thefreshloaf.com/lessons/advanced/sourdoughoutline#culture.

- ↑ Hansen, A.S. (2004). Sourdough bread. In Handbook of food and beverage fermentation technology. CRC Press.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Harris, L. (2003). Sourdough culture. Gastronomica: The Journal of Food and Culture, 3(3), 76-79.

- ↑ Diowksz, A., & Ambroziak, W. (2006). Sourdough. In Y. H. Hui (Ed.), Bakery Products: Science and Technology (pp. 365-380). Ames, Iowa: Blackwell Publishing.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Wagner, S. C. (2005). From starter to finish: Producing sourdough breads to illustrate the use of industrial microorganisms. The American Biology Teacher, 67(2), 96-101.

- ↑ Wood, E. (1996). World Sourdoughs from Antiquity. Berkeley, California: Ten Speed Press.

- ↑ Mayble Rose. (2010). Retrieved from http://mayblerose.wordpress.com/2010/07/11/

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Reinhart, P. (2001). The bread baker's apprentice: Mastering the art of extraordinary bread. Berkeley, California: Ten Speed Press.

- ↑ Nelson, Pamela. "How Sourdough Bread Works" 17 November 2000. HowStuffWorks.com. http://science.howstuffworks.com/innovation/edible-innovations/sourdough.htm 18 March 2012.

- ↑ Sadeghi, A. (2008). The Secrets of Sourdough. A Review of Miraculous Potentials of Sourdough in Bread Shelf Life , 2-3.

- ↑ Nelson, Pamela. "How Sourdough Bread Works" 17 November 2000. HowStuffWorks.com. http://science.howstuffworks.com/innovation/edible-innovations/sourdough.htm 18 March 2012.

- ↑ Nelson, Pamela. "How Sourdough Bread Works" 17 November 2000. HowStuffWorks.com. http://science.howstuffworks.com/innovation/edible-innovations/sourdough.htm 18 March 2012.

- ↑ Nelson, Pamela. "How Sourdough Bread Works" 17 November 2000. HowStuffWorks.com. http://science.howstuffworks.com/innovation/edible-innovations/sourdough.htm 18 March 2012.

- ↑ Nelson, Pamela. "How Sourdough Bread Works" 17 November 2000. HowStuffWorks.com. http://science.howstuffworks.com/innovation/edible-innovations/sourdough.htm 18 March 2012.

- ↑ Decock, Pieter; Cappelle, Stefan (January–March 2005). "Bread technology and sourdough technology" (PDF). Trends in Food Science & Technology 16 (1-3): 113–120.doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2004.04.012. Retrieved 2011 Dec 17.

- ↑ StockFood. (2012). Retrieved from http://international.stockfood.com/image-picture-Rustic-Loaf-of-Potato-Bread-on-Brown-Paper-Bag-00651984.html

- ↑ Karel, K. (2003). Handbook of Dough Fermentations. 72(13), 132-133