Course:ETEC540/2009WT1/Assignments/ResearchProject/SilentReading

Lindsey Martin

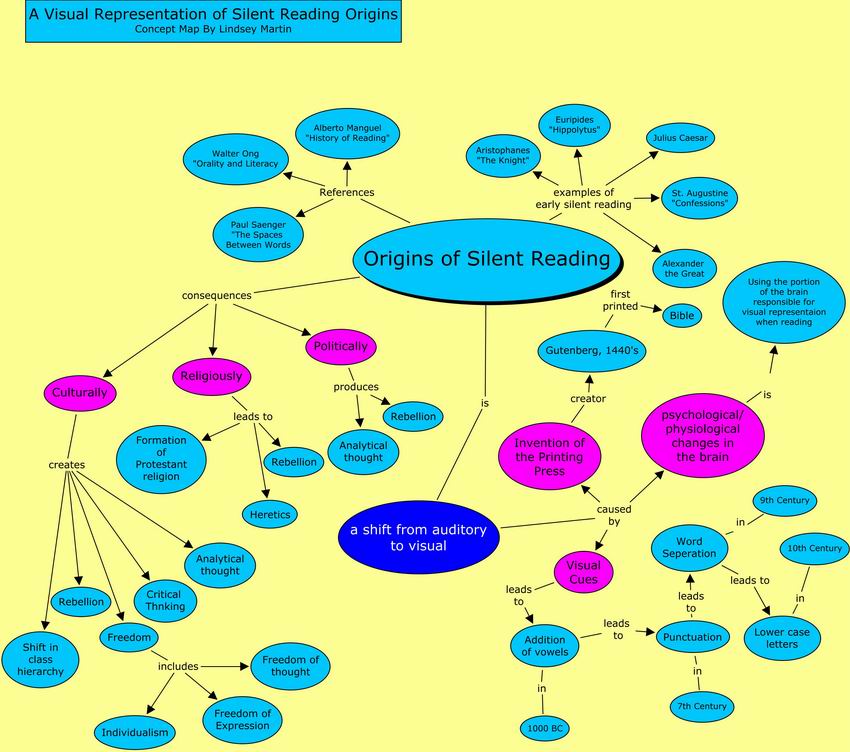

Visual Representation of Silent Reading

The Original Shift

Silent reading was a gradual procession as well as a fundamental change in the way humans thought and interpreted the written word. Walter Ong suggests that the invention of the printing press brought about the shift from oral or auditory reading towards visual and silent reading. Yet, history indicates that silent reading began a great deal earlier than Gutenberg’s invention in 1440. The first record of silent reading in the west came from 397 AD in Augustine’s "Confessions". Augustine recounts his days of observing St. Ambrose read and notes that “when he read, his eyes scanned the page and his heart sought out the meaning, but his voice was silent and his tongue was still” (Augustine, V1, 3). There are numerous points in history that indicate an earlier stance on reading where the tongue held still. Euripides’s "Hippolytus" has Theseus reading his dead wife’s letter silently on stage as well as Aristophanes’ "The Knight" in which Demosthenes reads a tablet silently to himself indicating he does not like what he sees. The greats of history also indicate that silent reading occurred before the invention of the printing press. Alexander the Great, according to Plutarch, read a letter in silence which shocked his army (Plutarch, On the Fortune of Alexander). As well, Julius Caesar has been noted to have read a letter silently in front of Cato (Plutarch, The Parallel Lines). Claudius Ptolemy in the second century AD stated that people read silently to themselves in order to study more effectively. He believed that reading aloud would be a hindrance to concentration (Ptolemy, On the Criterion). Alberto Manguel confirms that there are instances of silent reading in earlier history, but states that silent reading became a preferred tactic in the west around the tenth century (Manguel, History of Reading, Pg. 43). It is evident that silent reading occurred much earlier in history, but the widespread application of silent reading came about due to the spread of information caused by Gutenberg’s printing press.

Reading Quotes from history

Saint Isaac of Syria: “I practise silence, that the verses of my readings and prayers should fill me with delight. And when the pleasure of understanding them silences my tongue, then, as in a dream, I enter a state when my senses and thoughts are concentrated. Then when with prolonging of this silence the turmoil of memories is stilled in my heart, ceaseless waves of joy are sent me by inner thoughts, beyond expectation suddenly arising to delight my heart.”

Saint Isaac of Syria, “Directions of Spiritual Thinking” in Early Fathers from the Philokalia, Ed. & trans. E. Kadloubovsky & G.E.H. Palmer (London & Boston, 1954).

Isidore of Seville’s take on silent reading: “reading without effort, reflecting on that which has been read, rendering their escape from memory less easy”

Isidoro de Sevilla, Libri sententiae, III, 13:9, quotes in Etimologias, ed. Manuel C. Diaz y Diaz (Madrid, 1982-83).

Silent Reading and Religion

Silent reading had profound implications for many aspects regarding religion. It provided people with an involvement with their faith that had not occurred in the past. Silent reading allowed for the inward meditation of religious ideas providing common people to think and react on religion as opposed to accepting an authority figures’ interpretation. The shift was primarily for average lay people to have the ability to reflect on their own thoughts about religion. In fact, the first mass produced item created by Gutenberg’s printing press was a bible. The argument that ensued from this would change the face of religion in western cultures.

The origins of silent reading had profound implications for Christianity. After the creation of the printing press in the western world the amount of heresy went up exponentially. Before the average citizen had access to books or access to reading material, leniency existed for unbelievers. However the establishment of reading quietly without thought interuption saw an increase in the numbers of punishments. A correlation exists between the first burning at the stake for heresies and the popularity of reading silently. The first burning occurred in 1022 with a group of Canons and lay nobles, proving that independent readers were a threat to religious standards (Manguel, Pg. 55). The concern for most religious figure heads was that people would begin to question the authority of the church. Some, like Roman Theologian Silvester Prierias, regarded reading as an oral practice and petitioned for it to remain an oral practice within the church. Consequently, Prierias thought the book of the church should be read only by the authority of the Pope. Others like Martin Luther went down a different path. Luther’s private studies led him to the conclusion to question the church and its role. Luther’s legacy became the origins of the Protestant religion. The very shape of Christianity changed with the expansion of silent reading. Paul Saenger indicates that “a foreign text could be read even during the performance of public liturgy. Private, visual reading and private composition thus encouraged individual critical thinking and contributed ultimately to the development of scepticism and intellectual heresy” (Saenger, pg. 264).

However, there are some religions that to this day do not differentiate between reading and speaking. The primordial languages of the bible, Aramaic and Hebrew, do not differentiate between reading and speaking, indicating that religion and reading in the oral sense are related. The sacred text of the bible would require not just the eye, but the whole body. Many people would sway and speak aloud as they or someone else read so as nothing divine could be lost ( Manguel, Pg. 46). Another example is the Muslim faith, which also has a tendency to use the whole body as part of the reading process. In fact, the Islam rules for reading the Koran indicate the oral nature of reading. Rule number nine for reading the Koran states that reading and hearing are the same act, one must read “loud enough for the reader to hear it himself, because reading means distinguishing between sounds” (Bruns, 1992).

The Process of Silent Reading

The story of Saint Augustine and his process of silent reading:

Saint Augustine (354 - 430), Bishop of Hippo, experienced an ecstatic conversion to Christianity and a discovery of being able to read silently for the first time in the late summer of 386. His book, "Confessions", describes the experience: Augustine frustrated by being confined in the house ran outside and threw himself under a fig tree, where he burst into tears and spoke out to God. Unexpectedly he began to hear a voice commanding him to "Take up and read. Take up and read." Augustine seized a Bible opened it and read in silence the passage from the Epistle to the Romans (xiii, 13, 14) "Not in rioting and drunkenness, not in chambering and wantonness, not in strife and envying. But put ye on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make not provision for the flesh to fulfill the lusts thereof." Augustine adds to this account. "I had neither desire nor need to read any further." (Confessions, VIII. xi. 30). What Augustine did for the first time was startling. People could not figure out the trick. How could he understand without hearing the words? Was he reading or pretending to read? The idea then was that the book spoke to the reader, much as one person spoke to another. Silent reading was a surprise.

Picture of St. Augustine Source: http://www.flickr.com/photos/glennl/3864546134/

The Psychology of Silent Reading

The establishment of silent reading created a cultural shift and with it a fundamental change in human brain function. Manguel indicates that words were not sounds when the eye perceived them, but rather they were sound themselves (Manguel, 1996). The history of writing and ultimatley reading, changed with the creation of punctuation, word spaces, and the invention of the printing press. Yet, what happened to the physical brain? The American psychologist Julian James stated that humans have a bicameral mind in which one hemisphere of the brain is more suited to read silently (James, 1996). James also concluded that the method of brain interpretation of words changed from an aural to visual form. “Reading in the third millennium BC may therefore have been a matter of hearing the cuneiform, that is, hallucinating the speech from looking at its picture-symbols, rather than visual reading of syllables in our sense” (James, 1976). Sebastian Wren wrote a short paper for SEDL entitled Understanding the Brain and Reading.

Read Wren’s paper and look at the images of the active brain while engaged in silent reading: http://www.sedl.org/reading/topics/brainreading.html

Wren provides an explanation for silent reading from a physiological perspective, he states:

What seems to be happening is that the brain is analyzing text at three major levels - the visual features of the words and letters, the phonological representation of those words, and the meanings of the words and sentences. There are other parts of your brain that are also quite active when you are reading (e.g. parts of the cerebellum controlling automatic eye movements, parts of the reticular formation responsible for attention, etc.), but the most significant activity is that associated with these three areas of processing. (Wren, http://www.sedl.org/reading/topics/brainreading.html ).

Wren concludes that the parts of the brain responsible for visual analyzation are active during silent reading, which reinforces the notion that we perceive the written word in a visual form. It is impossible to provide brain scans of those from the past, therefore we can only speculate that the brains of those who read in an auditory form would have had different areas of their brains activated.

Visual Cues – Punctuation & Word Separation Resulting in Silent Reading

A differing perspective for the switch from oral/auditory reading to silent, visual reading comes primarily from Paul Saenger and his work "The Space Between Words The Origins of Silent Reading". Saenger contends that it was not the invention of the printing press alone that caused the shift in reading aloud to reading silently, but a form of visual cue in the structure of writing that resulted in the shift. Saenger attributes the introduction of punctuation and word separation, which greatly aided mental visual recognition of words, as the origin for silent reading. It began with adding vowels which then led to word separations, capital letters, punctuation, and resulted in the ability to read silently. The evolution occurred overtime. The 7th century saw the high dash as a comma, a series of points and dashes which indicate stops in the written document. By the 9th century scribes were separating each word, most likely for aesthetic reasons and not convenience. Soon after the Irish created punctuation which leads to the 10th century use of new paragraphs as indicated by a larger letter (Manguel, pg. 46). Saenger realizes the importance of the spaces of words for reading and our ability to do so silently. He calls this “aerated script” and stresses that the shift to spaces in words enabled us to look upon written text in a visual sense and led to our ability to read it without the use of sound (Saenger, pg. 32).

Visual Representation - Pictures That Tell A Story

The outbreak of the visual and silent reading can also be seen through Medieval churches. The stained glass images are pictures that tell a story, indicating, perhaps, a start to silent reading as onlookers would gaze at the images and "read" the story the images convey.

A Medieval Church in Prauge.

Source: http://www.flickr.com/photos/tjflex/2149749662/

A Medieval Church in Prauge.

Source: http://www.flickr.com/photos/tjflex/2149749662/

Table - The Origins of Silent Reading

| In 2000 BC, the Phoenicians developed the first methods to represent spoken language - an alphabet consisting entirely of consonants | SPKNWRDSRTHSYMBLSFMNTLXPRNCND

WRTTNWRDSRTHSYMBLSFSPKNWRDS. |

| In 1000 BC, the first major upgrade occurred in the technology of representing language - the Greeks added vowels to the alphabet. This is essentially the same alphabet we use today - and it is considered one of humanity's greatest inventions. | SPOKENWORDSARETHESYMBOLSOFMENTALEXPERIENCEAND

WRITTENWORDSARETHESYMBOLSOFSPOKENWORDS. |

| About 1000 years later, in 200 BC, the next major upgrade in writing appeared: punctuation marks. Punctuation was first observed in Alexandrian manuscripts of plays written

by Aristophanes. |

SPOKENWORDSARETHESYMBOLSOFMENTALEXPERIENCE,AND

WRITTENWORDSARETHESYMBOLSOFSPOKENWORDS. |

| Yet another 1000 years passed before the next improvement in text, namely the invention of lower case characters by Medieval Scribes. | Spokenwordsarethesymbolsofmentalexperience,and

writtenwordsarethesymbolsofspokenwords. |

| About 1000 years ago, in 900 AD, the last major upgrade in text took place: the insertion of spaces between words. Also developed by Medieval Scribes, this invention made

it possible, for the first time, for the vast majority of readers to be able to read silently. Prior to this, most readers had to read out loud in order to be able to read at all. |

Spoken words are the symbols of mental experience, and

written words are the symbols of spoken words. |

Private Reading and Personal Expression: A Cultural Shift

The conversion to silent reading has had an acute reaction for the majority of western culture. In the beginning, many nobles and Kings did not read for themselves but were read to instead. As it became more apparent that reading could be done silently, nobles around the 14th century began to accept it as a viable form of information gathering. Reading silently became particularly popular when Kings themselves began to read using their internal voice. The growing practice of silent reading by the aristocracy created major changes for the general population. It provided the lower classes with the opportunity to read more and more often due to the availability of printed books all because more nobles were taking up reading independently. The aristocracy made reading, as Ong suggests, a commodity (Ong, pg. 127) which meant more books were available and in turn filtered down to the average citizen. The ability for the masses to learn independently causes revolution, diverse opinions, deeper thoughts, and inventions of all kinds. Saenger shows the consequences of silent reading on the general public and the scholastic culture: “Alone in his study, the author, whether a well-known professor or an obscure student, could compose or read heterodox ideas without being overheard. In the classroom, the student, reading silently to himself, could listen to the orthodox opinions of his professor and visually compare them with the views of those who rejected established ecclesiastical authority” (Saenger, pg. 264).

The cultural shift included other institutions besides academia. The nature of the library changed due to the shift towards silent reading. Saenger observes that the physical design of libraries changed drastically. This design transformed from a forum for listening to a private world with tables and individual cubicles for study. Libraries also made a transition from a place of sound to a silent and quiet atmosphere. Silent reading created the library of today, one with silence and is visually formatted. The visual format is most evident with the creation of reference tools and the structure of displaying books.

Yet the critical changes to culture due to silent reading resided within the self. With the onset of silent reading the incidences of cynicism and scepticism went up. The occurence of silent reading fostered an individuals ability to make intellectual judgements. Silent reading creates for the first time a method of gaining information where no one can see or hear you obtaining that informaiton. Accountability for what one is reading is on the individual instead of the group. The privacy of reading fosters personal expression and the freedom of exploration into topics considered taboo. In fact, with the onset of silent reading comes an increase in books that deal with human sexuality. Silent reading also allows the reader more time to think and reflect upon information, making it a medium for subversive political thought. More people interpreting and reflecting on ideas is the result of much political change within the western world. The Reformation period being the greatest example of political change as a result of the implementation of new ideas. Reading in silence, as suggested by Walter Ong, provides the “drift in human consciousness towards greater individualism” (Ong, pg. 129). Private reading creates the need or desire for more reflective thinking and more privacy in general.

Conclusions

Religiously, politically, and historically, it is evident that the shift into silent reading played a role in the shaping of human nature in the western world. The shift from oral to visual reading caused changes physically in the brain, and psychologically with the turn towards the self and privacy. The new interpretation of the written word could not have been read silently without major changes to the look of medieval manuscripts. These words would never have made it to the masses without the invention of the printing press. Silent reading fostered independent learning and the beginnings of critical thinking. Questioning authority and challenging ideas creates many political and cultural changes. The origins of silent reading indicates changes in interpretation of words, the spaces between words, and how we physically see those words. The origins of silent reading also provides us with an indication of where we are heading. The future with digital mediums as a norm will change our outlook both internally and within the structure of western culture.

References

Bruns, Gerald L. (1992). Hemeneutics Ancient and Modern. London: New Haven.

Jajdelska, Elspeth (2007) Silent Reading and the Birth of the Narrator. Toronto: University of London Press.

James, Julian. (1976). The Origins of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind. Princeton.

LiveInk (2008). A Brief History of Reading. Retrieved from http://www.livebook.com

Manguel, A. (1996). A History of Reading . New York: Viking Penguin.

Ong, Walter (1982) Orality and Literacy. London and New York: Routledge.

Plutarch “Brutus”, v, in The Parallel Lives, ed. B. Parrin (1970). London: Cambridge.

Plutarch, “On the Fortune of Alexander”, Frangment 340a, in Moralia, Vol. IV, ed. Frank Cole Babbitt (1972) . London: Cambridge.

Ptolemy, Claudius. On the Criterion. Discussed in The Criterion of Truth, ed. Pamela Huby & Gordon Neal (Oxford, 1952).

Saenger, P. (1997). Space Between Words: The Origins of Silent Reading . Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Saint Augustine (397 AD) Confessions. Paris, 1959 V, 12.

Wren, S. (2009). Understanding the Brain and Reading . Retrieved from http://www.sedl.org/reading/topics/brainreading.html