Course:ENGL419/Books/Sesshoseki

Sesshōseki gonichi no kaidan

The Text

Sesshōseki gonichi no kaidan (Japanese 殺生石後日怪談) was written by Kyokutei Bakin (曲亭馬琴)and serialized between 1824 and 1833. In English, the title translates to something like "The Mysterious Tale of the Days After the Killing Stone." There are five parts spanning ten volumes; each part is split into a first half (J. jō 上) and second half (J. ge 下). It was printed from carved wood blocks on paper that was folded along the outside edge and bound with thread along the other edge. Along the fold of each page there is a mark indicating the title of the work and page number. It is difficult to pin down a specific genre for this work. It is a kanazōshi, a term that covers a large variety of vernacular printed books of approximately this shape, size, and length, but with different colored covers that indicate the type of content. As for the subgenre of kanazōshi, it may be a gōkan (合巻, "combined volume") or it may be a yomihon (読本, a book that emphasized the text over the pictures). A more accurate sense of the content than I have been able to provide here might help make the distinction.

Edo Literary Style

The Edo period spanned from 1603 to 1868. One of the hallmarks of Edo-period literature was the interplay between the idea of ga (雅, elegance) and zoku (俗, vulgarity). While these ideas had existed before the Edo period, Edo authors mixed classical Chinese together with classical Japanese in their writing style, and in terms of content, they were not afraid to tackle lowbrow topics in an effort to balance "high" content and introduce satire and parody into their works. In gesaku (戯作 "playful") comic literature, the author often combined a "high" writing style (classical Chinese) with a "low" contemporary setting (such as the pleasure quarters). The strange elements of folktales also became a popular topic, as we see in Sesshōseki gonichi no kaidan. Kyokutei Bakin was well-known for being an author of gesaku.[1]

Text and Image

One of the particularly interesting points about this kind of book is the interplay of text and image. If you examine the image on the left (An Example of the Interplay of Text and Image in Volume 1 of Sesshōseki gonichi no kaidan), you can see that the text has been inserted in between elements of the image. This allows the printer, author, and illustrator to make the absolute most of the available space while providing a particularly engaging reading experience for its audience. The text may contain the continuing narrative of the story, the dialogue of the characters in the image, or descriptions of what is going on in the scene, depending on the image and the work. In the image provided here, the text is primarily dialogue between the characters.

Introduction

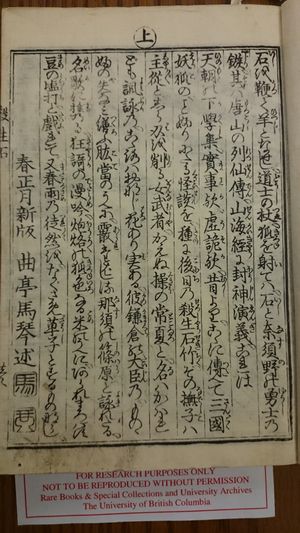

The following is a transcription of Kyokutei Bakin's introduction at the beginning of Volume 1, Part 1. The transcription is line by line, starting from the upper right part of the image in the traditional right-to-left, vertical writing style. Readings provided over the characters in the text are given in parentheses here.

石を鞭(うつ)て羊(ひつじ)となせし、道士(どうし)の杖(つゑ)、狐(きつね)を射てハ、石と奈須野(なすの)の勇士(ゆうし)の

鏃、其(それ)ハ唐土(もろこし)の列仙傳(れつせんでん)、山海経(せんかいきやう)に封神演義(ほうじんゑんぎ)、これは

天朝(ひのもと)の下学集(かかくしふ)、實事歟(まことか)、嘘詭歟(うそか)、昔(むかし)より、ここに傳(つた)へて三国(さんごく)

妖狐(えうこ)の、ことふりにたる怪談(くわいだん)を、種(たね)に後日(ごにち)の殺生石竹(せつしやうせきちく)、その撫子(なでしこ)ハ

主従(しゆうじゆう)と、しら刃(は)を削(けづ)る女武者(おんなむしや)、かえぬ操(みさほ)の常夏(とこなつ)と、名ハかハれ

ども諷詠(よミぶり)の、ここ詠ハおなじ花(はな)あり実(ミ)ある、彼(かの)鎌倉(かまくら)の大臣(たいじん)の、ものゝ

ふの矢(や)なミ繕(つくろ)ふ肱當(こて)のうへに、霰(あられ)たとばしる那須(なす)の篠原(しのハら)と詠(よま)れたる、

名歌(めいか)に携(すが)る、狂歌(きやうか)の漫吟(でたらめ)、炮烙(ほうろく)の狐色(きつねいろ)なる米(こめ)のうへに、あられまつバす

豆(まめ)の塩打(しほうち)、と戲(たハふ)れて、又(また)春雨(はるさめ)の徒然(つれづれ)を、なぐさめ草子(ざうし)とするものならし

春正月新版 曲亭馬琴述 [seal]

A direct translation would be difficult, as Bakin enjoys using alternative Chinese characters in order to create puns and references many other works, but in summary, he is discussing the precedents for the story of the Killing Stone and how he used them as a jumping-off point to create his own tale. The last line on the far left includes the phrase "newly printed at the beginning of spring" (the start of the new year by the lunar calendar) and Bakin's name and seal.

A typeset edition of the full text of Sesshōseki gonichi no kaidan, with the exception of the introduction and image text, is available on Japan's National Diet Library website: http://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/878824. The text has not yet been translated into English.

The Author

Kyokutei Bakin (J. 曲亭馬琴) (1767-1848) is also known by the name Takizawa Bakin (滝沢馬琴). He was born and raised in Edo (modern Tokyo) Japan as the son of a samurai. In 1790 he began working with the writer and artist Santō Kyōden (1761-1816) and began writing various yomihon. He became a very popular author, and is best known for yomihon such as the Eight Dog Chronicles (J. Nansō satomi hakkenden 南総里見八犬伝) which, at 106 volumes, is one of the world's longest novels.[2]

Precedents: Otogi-zōshi, Noh Plays, and Legends

Tamamo no mae

Tamamo no mae (玉藻前)is an otogi-zōshi or "companion tale," a genre of short story from the Muromachi period (1337-1573). These tales are generally found either in small books called Nara ehon (奈良絵本) or in small scrolls. The content of these tales vary widely, but are generally humorous and entertaining and intended for a wide audience.

In Tamamo no mae, retired Emperor Toba (1103-1156) falls in love with a mysterious woman and then becomes gravely ill. The woman's name is Tamamo no mae, and a diviner informs the emperor that she is actually an eight hundred year old fox spirit who has already caused trouble in both India and China, and is now making Emperor Toba sick. Tamamo no mae is killed and turned into a stone that emits toxic gas and kills whoever comes near.[3]

Sesshōseki

The plot of Bakin's tale appears to be based on the plot of the Noh play Sesshōseki (殺生石, The Killing Stone). According to Shimazaki and Comee's work on Noh plays and their classifications, this play is either classified as an ingyō-mono (a strange-apparition piece) or as a type of action-dance play known as a kaijin-mono (a non-human spirit play). As of the publication of Shimazaki and Comee's book Supernatural Beings from Japanese Noh Plays of the Fifth Group in 2012, this play was still part of the active repertoire of all five schools of Noh theater (Hōshō, Kanze, Kongō, Kita, and Konparu).[4]

In the play, a priest and his attendants are crossing Nasu Plain when they see a bird die while flying over a rock; when they go to investigate, a woman tells them that the rock is a fox spirit known as Princess Tamamo in her human form. She was once in love with the Emperor, but was sent away from him and so turned into a rock that would kill any who passed by. The woman then admits that she is in fact the spirit of the rock. When the priest and his attendants pray and make offerings, the rock splits in two and a fox comes out and dances, showing that the priest's actions have saved its soul.[5]

The Source of the Legend

The Sesshōseki, or Killing Stone, appears in legend as a stone with the ability to kill anything that comes near it. There may, however, be a real-life origin for this legend. The Noh play refers to the Nasu Plain, which is near the volcanic Nasu Mountain in Tochigi Prefecture. Hot springs in the town of Nasu are fueled by magma from the mountain. Thus, it is not a toxic stone, but rather the toxic sulfurous gases that likely spawned this legend.[6] In Tochigi Prefecture, there is even an actual stone believed to be the Sesshōseki.[7]

Further Reading

For more information on Edo period print culture:

Jones, Sumie and Watanabe Kenji. An Edo Anthology: Literature from Japan's Mega-City, 1750-1850. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2013.

For information on the various genres of kusazōshi, particularly kibyōshi, including lots of images and translations:

Kern, Adam. Manga from the Floating World: Comic Book Culture and the Kibyōshi of Edo Japan. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2006.

For information on otogi-zōshi, see:

Ruch, Barbara. "Origins of the Companion Library: An Anthology of Medieval Japanese Stories." The Journal of Asian Studies, 30:3 (May 1971).

Skord, Virginia. Tales of Tears and Laughter: Short Fiction of Medieval Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 1991.

References

- ↑ Jones, Sumie and Watanabe Kenji. An Edo Anthology: Literature from Japan's Mega-City, 1750-1850. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2013, pp. 21-22.

- ↑ Shirane, Haruo. Early Modern Japanese Literature: An Anthology, 1600-1900. New York: Columbia University Press, 2002.

- ↑ Reider, Noriko T. "Animating Objects: Tsukumogami ki and the Medieval Illustration of Shingon Truth." Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 36:2, 2009, p. 248

- ↑ Shimazaki, Chifumi and Stephen Comee. Supernatural Beings from Japanese Noh Plays of the Fifth Group. New York: Cornell University East Asia Program, 2012.

- ↑ Maruoka, Daiji and Tatsuo Yoshikoshi. Noh, trans. Don Kenny. Osaka: Hoikusha, 1983.

- ↑ Watanabe Shōgo 渡邊昭五. "Sesshōseki." JapanKnowledge Database. Accessed April 22, 2015. http://japanknowledge.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/lib/display/?lid=1001000132790.

- ↑ "Sesshō." JapanKnowledge Database. Accessed April 22, 2015. http://japanknowledge.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/lib/display/?lid=2001010401900