Course:ENGL419/Books/Phantastes

Introduction to Phantastes

I have chosen to write about the first edition of George MacDonald’s Phantastes: A Faerie Romance for Men and Women, published in October 1858 and available in Rare Books & Special Collections at UBC under the call number PZ6 1858 M323. The book is significant because it is George MacDonald’s first novel, and because it's an early example of a fantasy novel. While most Victorian fantasy is aimed at children, Phantastes was described by MacDonald as an adult fairy story.

I will organize my research in a roughly chronological form, moving from authorship, to book production, to the characteristics of the printed book’s interior, to the reception of the book, and finishing with information on the more recent history of this specific copy.

George MacDonald and Victorian Authorship

Although George MacDonald trained to be a pastor and worked in that job for several years, his sermons were found unsatisfactory and he was forced to find some other source of income[1] The need for money provided a strong incentive to publish: he began Phantastes in the absence of any pupils to teach, and he writes in a letter to his father than he is “writing a kind of fairy-tale in the hope that it will pay me better [...] I don’t know what it will be worth yet.”[2]

MacDonald found his publisher, Smith, Elder and Co., after fellow author F.D. Maurice had recommended the firm to him during a visit to London. Two days after submitting the manuscript, he'd been given an offer - it turned out his efforts were worth £50.[3] This compares to the £20 he received for his first book of poetry, Within and Without,[4] and the £90 for his next novel David Elginbrod.[5] Though MacDonald’s publications established him as a professional writer, the payment he received was modest compared to the most famous novelists of the day – Charles Dickens for example could receive £10,000 for a single novel.[6]

The limitations of MacDonald's publishing income meant that he sometimes had to turn to other sources to earn a living. These included going on lecture tours and participating in the theatrical productions put on by his family.[7] Even as late as 1887, when he was well established as a novelist, George MacDonald wrote to a friend asking for the “usual kind gift.”[8]

A number of factors contributed to the limited profitability of writing for authors like MacDonald. For one thing, the success and scale of publishing (particularly fiction publishing) was new for everyone, and many authors didn't understand their value to publishers. In 1850s Britain it was still the norm for authors to be paid an upfront sum for the rights to their work, which meant that they wouldn't receive any additional royalties if their book was a bestseller, or if it was published in additional editions. Authors wishing for something like the royalty-sharing contracts that were more common in America would have to work out a complicated copyright leasing agreement with their publisher, and most authors were either unable to or didn't bother.[9]

Piracy of British books in America was also a significant problem for authors for most of the nineteenth century; though MacDonald attained a reasonable level of success in America, he never saw any money from book sales there. A treaty on copyright between the British and American governments was actually signed in 1852, but it failed to obtain the necessary votes in the US Senate, apparently because British authors and publishers didn't understand the need to spend large sums of money lobbying American politicians.[10]

Book Production

Publishing

The title page of the work identifies the publisher as “London: / Smith, Elder and Co., 65, Cornhill.” At the bottom of the final page of the book, the publisher is again identified: “London: Printed by Smith, Elder & Co., Little Green Arbour Court, E.C.” Smith, Elder & Co was a respected firm known to pay generously for books with commercial potential, and it gained a reputation of being the most important Victorian publisher of fiction.[11]

Fiction itself, of course, achieved a unprecedented popularity in the nineteenth century.[12] Charlotte Bronte's Jane Eyre was a major success for Smith, Elder & Co., but it also published other prominent novelists of the day including George Eliott, William Makepeace Thackeray, Robert Browning, Alfred Tennyson, Thomas Hardy, and Arthur Conan Doyle. A growing overseas trade was also profitable, and between 1851 and 1861 the money going through the firm’s banking account increased from £57,506 to £405,163.[13]

Printing

While most English publishers of the period outsourced printing to other publishers, Smith, Elder & Co. was one of the few that owned its own printing press.[14]

Typesetting would have been done by hand, as it had been for hundreds of years; the mechanization of this process only began to occur at the end of the nineteenth century, and was introduced by newspaper printers before adopted for books.[15]

Metal rather than wood began to be used for the hand press in the early part of the nineteenth century.[16] Steam printing was also developed. By the time Phantastes was published not only newspapers but some books, especially those with larger print runs, were printed with steam.[17]

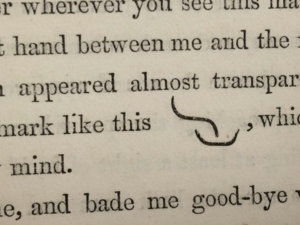

The use of lithography – writing on polished limestone – was also developed for illustrations as well as graphs, tables, certain languages in non-Latin scripts, and anything else that required similar graphics.[18] While Phantastes contains no illustration, it seems likely that the symbol contained in the text of the book (discussed below) was created with lithography.

Binding

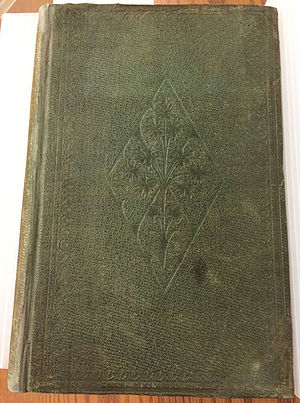

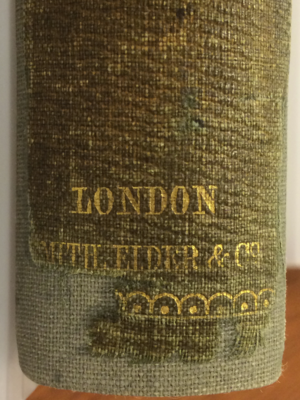

The book is bound in a subdued green cloth. The front and back covers are identical; both seem to be blind-stamped with a plant enclosed in a diamond-shaped design in the middle, with decorative edgings around the border. The spine has gold, capital lettering, with “Phantastes / A / Faerie / Romance” on the top, followed by a leaf design; the words “By Mac Donald” in the middle; and “London / Smith Elder & Co” at the bottom, followed by a border consisting of a series of half-circles.

Several features of the Phantastes design are direct results of developments made in the first half of the century. The use of cloth-covered casing was introduced around the 1830s and provided more permanence than board binding at a far lower price than leather.[19] Gold blocking on cloth was introduced shortly after cloth covers, and blind stamping or blocking – the practice of embossing or impressing without ink or foil – was inroduced soon after that.[20] Both developments were standard by the time Phantastes was published.[21]

Searching for images of the 1858 Phantastes reveal many identical bindings, which suggest that the book was produced with an edition binding – that is, the entire print run was produced with identical bindings as part of the publication process.[22]

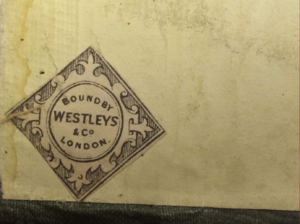

A small piece of paper attached to the inside rear cover, called a ticket, identifies Westleys & Co as the binder of this copy of Phantastes. It was common for binders to advertise their craft with tickets, which were usually rectangular but could appear as ovals or other shapes after the middle of the century.[23] Westleys & Co in particular makes ample use of binders' tickets, and the design found in Phantastes was typical from 1853-63.[24]

Even for English publishers that printed their own books, it was rare to also bind them in-house; so outsourcing the task to specialists like Westleys & Co was the standard.[25]. Many publishers had a preferred binder, although they did not stick to a single company exclusively.[26]

Interior Content

Introductory quote

A German quote from Novalis appears at the beginning of the work without translation. It is possible that some of MacDonald's more educated readers would have understood it - The Leader's review of Phantastes inserted a portion of the Novalis quote and claimed that they translated it only "for the benefit of country gentlemen" - but it is hard to believe that George MacDonald actually expected most of his readers to understand it. It is more likely that he doesn't care whether his readers understand it or not, and that the quote is present for its own sake rather than to be understood.

The paradoxical nature of text that is both meant and not meant to be read is certainly interesting, and it would seem to emphasize Phantastes as an object rather than merely a story. Several subsequent editions have changed this aspect of the text, either leaving the quotation out completely or displaying only its English translation.

Title page

Phantastes appears in bold capital letters at the top, followed by the subtitle in a gothic or blackletter font. The format of the subtitle stands out by being the only instance of the font on the page or indeed in the entire book, and it seems to emphasize the old-fashioned Romance aspect of the text.

The author is listed next. The title of his previous work and short quotation beneath both point to the role that the title page plays in selling the book to the reader and in informing them about the type of story contained within.

The publisher and publication date appears at the bottom of the title page, followed by the words “[The right of translation is reserved]” in italics. An explanation for this statement appears in an 1885 edition of The Publishers’ Weekly: “in England the right of translation may be reserved under the international copyright provisions, notice being given on the title page.”[27] By the 1850s, England had signed reciprocal copyright protection agreements with a number of European states that would have protected translation rights.[28]

Chapter headings

Chapters are numbered with roman numerals and contain short quotes, or multiple quotations, from other sources. The practice seems to emphasize the intertextuality of Phantastes - and while almost all books are inspired by other work, the process of borrowing material seems more obvious in a fantasy novel that is more obviously separated from daily life. Several of the quotations are in German, but here translations are provided next to the original text.

Interior text characteristics

The font appears similar to Caslon, although identifying a precise font is difficult.

The text is frequently broken up with songs, some of which run to several pages. The text of these is printed in a smaller size and is indented, and the unique song formatting is used even for a snatch of song that consists of a single line and could easily be included as a quotation in the main text. While some of this formatting might be in line with conventions of the time, the way that songs are presented emphasizes their importance.

Another notable feature of the text occurs on page 235. Here, as shown in the image, the the narrator describes seeing a "mark like this,” followed by a small sketch of the shape within the text itself, followed by a comma. The use of an in-text symbol as though it were a word seems unusual in any period, and it stands out all the more because there are no other symbols or even illustrations elsewhere in the book. A similar technique is used almost a century later in the first chapter of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Fellowship of the Ring.

Phantastes and Victorian Readership

Sales and Distribution

Upon publication, Phantastes was advertised in The Morning Post through October and November 1858. The initial advertisement included the text “Just ready, 1 vol., post 8vo.,” followed by the title, author, and publisher. “8vo” refers to the octavo size of book, and “post 8vo” refers to a specific size of octavo, 8”x5”.[29] Given the limited space of the advertisement, it's reasonable to assume that the readers of The Morning Post were expected to both know and care about these sizes.

Several variations on this initial advertising copy appear in subsequent editions. The November 30 edition includes a critical quote about the work, and also lists a price of 10s. 6d, which was the standard for a traditional one-volume work of fiction.[30]

The November 10 edition includes the text “now ready, at all libraries.” Many middle class readers joined a subscription library like Mundie's rather than purchasing the books themselves, and library sales could be significant for publishers. The advertisement suggests that the publisher wished to encourage demand for the book in lending libraries, in addition to spurring more direct sales.

Reception of Phantastes

The reception of Phantastes among book reviewers was mixed.

Phantastes is advertised with other new publications in the back of an unrelated pamphlet in 1859, and it includes positive review excerpts from the Globe, New Quarterly, Daily Telegraph, Leader, and Literary Gavette.[31]

On the other hand, the Morning Chronicle published a particularly negative review in its November 10 edition. The reviewer writes that the lesson of the piece “has been conveyed in a much smoother and much better constructed sentence many times before, and it hardly required a visit to fairyland to obtain it for the benefit of mortals.” In closing, the reviewer says “we cannot but regret that one who had given such good promise in his previous work […] should, by the present publication, have afforded evidence that genius is no exception to the fairies’ ballad, ‘Alas, how easily things go wrong.’”

The Leader review, though somewhat lukewarm, talks of "quaint merits" and praises the "fancy" displayed in the "very fanciful work" while denying it any seriousness.

Is interesting to consider these reviews in light of Karen Michalson's book Victorian Fantasy Literature. She makes the point that novels in general were criticized for being fanciful and untruthful, something that Dickens seems to parody in Hard Times: "Now, what I want is Facts. Teach these boys and girls nothing but Facts. Facts alone are wanted in life. Plant nothing else, and root out everything else." If these attitudes appear in relation to realistic fiction, they are even more applicable to fantasy, and some of the scornful or deprecating content in the above reviews seems aimed specifically at the fantasy element.

Recent History

A card on the inside front cover of Phantastes notes that it is a part of the Arkley Collection of Early & Historical Children’s Literature. The Library and Archives Canada website gives some background information on the history of the collection:

The collection was established in 1963. The initial collection, the Malin-Edmonds Collection, was purchased from the duplicate collection of the Free Library of Philadelphia. In 1966, a collection of Lewis Carroll material was added. In 1976, the Arkleys donated their collection of nineteenth and early twentieth century books. Since then, the collection has been loosely called the Arkley Collection. [32]

The collection continuously accepting donations, however, so it is difficult to say exactly when Phantastes was added.

The fact that the book is a part of the Arkley collection at all is somewhat odd. George MacDonald published several popular children’s fantasies such as The Princess and the Goblin in his lifetime, but Phantastes is a book for adults, something that both the author and publisher are explicit about - even the subtitle indicates that it is for "men and women" as opposed to "boys and girls."

Writing in pencil on the first page states that the book is a first edition, describes some minor damage, and lists a price of $45. A search of used booksellers AbeBooks and Alibris suggest that a similar copy would cost a minimum of $1,500 as of April 2015.

Conservation Treatment

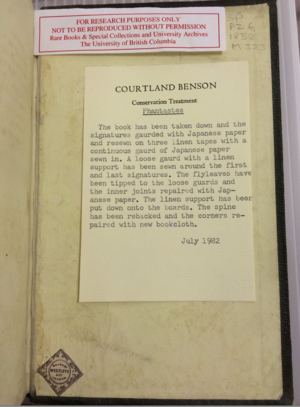

A card attached to the rear inside cover of the book, dated July 1982, describes the conservation treatment provided by Courtland Benson:

The book has been taken down and the signatures guarded with Japanese paper and resewn on three linen tapes with a continuous guard of Japanese paper sewn in. A loose guard with a linen support has been sewn around the first and last signatures. The flyleaves have been tipped to the loose guards and the inner joints repaired with Japanese paper. The linen support has been put down onto the boards. The spine has been rebacked and the corners repaired with new bookcloth.

Courtland Benson is a bookbinder residing in Victoria, BC who specializes in period-style binding and restorations.[33]

The description of the repairs seems thorough, but some of the terms may require further explanation for those not experienced in bookbinding and restoration techniques.

The term “take down” here appears to be used in the sense of “To take apart; dismantle.”

A signature is defined as a section or gathering of a book to which a signature mark is applied, to assist in the binding process. (A signature mark, in turn, is a letter and/or number applied to a section to help in the process of gathering the sections together. Phantastes' signature marks take the form of letters and numbers together.)[34]

The act of guarding refers to placing a strip of cloth or paper into a section of the book, in order to reinforce the paper and prevent the thread from tearing through. Guards refer to the strip of cloth or paper in question.[35]

Japanese paper, also known as Japanese tissue or Japanese copying paper, is a thin and strong paper useful to book repair. Among other things, it is used to reinforce the folds of sections, to repair the hinges that attach the endpaper, and to reattach signatures.[36]

Linen tapes are pieces of linen cloth to which the sections or “signatures” of a book are sewn, and which are attached to the boards at the ends.[37]

Fly leaves refer to the leaves at the beginning and end of a book that are not pasted to the boards or covers.[38]

Tipping is pasting the edges of a section to an adjacent section.[39]

Rebacking is “the renewal or replacement of the material covering the spine of a book” and can also refer to the replacement of the original spine material after repair or restoration. The photo of the bottom of Phantastes' spine appears to show the original, worn-away cloth cover in green, with the lighter cloth used it the restoration showing through beneath it.[40]

Bookcloth is a term for the fabric used to cover books, usually woven cotton fabrics.[41]

References

- ↑ Robb, David. MacDonald. p. 8

- ↑ Raeper, William. George MacDonald. p. 143

- ↑ Raeper, William. George MacDonald. p. 144

- ↑ Raeper, William. George MacDonald. p. 117

- ↑ Raeper, William. George MacDonald. p. 181

- ↑ Raeper, William. George MacDonald. p. 181

- ↑ Robb, David. MacDonald. p. 16

- ↑ Robb, David. MacDonald. p. 8

- ↑ Law, Graham. “The Professionalization of Authorship.” The Nineteenth-Century Novel 1820-1880. Eds. Kucich and Taylor. p. 39

- ↑ Feather, John. A History of British Publishing. p. 136

- ↑ Weedon, Alexis. "12 The Economics of Print." In The Oxford Companion to the Book. : Oxford University Press, 2010. See also: "Smith, Elder & Co." In Oxford Reader's Companion to George Eliot, edited by Rignall, John. : Oxford University Press, 2001.

- ↑ Shattock, Joanne. “The Publishing Industry.” The Nineteenth Century Novel 1820-1880 ed. Kucich and Taylor. p. 3

- ↑ Glynn, Jenifer. Prince of Publishers. p. 113

- ↑ Ball, Douglas. Victorian Publishers’ Bindings. p. 101

- ↑ Feather, John. A History of British Publishing. 2nd ed. p. 88

- ↑ Feather, John. A History of British Publishing. 2nd ed. p. 89

- ↑ Feather, John. A History of British Publishing. 2nd ed. p. 89

- ↑ Feather, John. A History of British Publishing. 2nd ed. p. 89

- ↑ Ball, Douglas. Victorian Publishers’ Bindings. p. 15

- ↑ Ball, Douglas. Victorian Publishers’ Bindings. p. 15

- ↑ Ball, Douglas. Victorian Publishers’ Bindings. p. 42, 50

- ↑ "edition binding." In The Oxford Companion to the Book, edited by Suarez, Michael F., and H. R. Woudhuysen. : Oxford University Press, 2010.

- ↑ Ball, Douglas. Victorian Publishers’ Bindings. p. 117

- ↑ Ball, Douglas. Victorian Publishers’ Bindings. p. 191

- ↑ Ball, Douglas. Victorian Publishers’ Bindings. p. 101

- ↑ Ball, Douglas. Victorian Publishers’ Bindings. p. 106-7

- ↑ The Publishers’ Weekly, Volume 28 - August 29, ’85 p. 245

- ↑ Feather, John. A History of British Publishing. p. 135

- ↑ http://www.trussel.com/books/booksize.htm

- ↑ Feather, John. A History of British Publishing. 2nd ed. p. 123

- ↑ ”Speech of the Right Hon. Lord Stanley” http://www.jstor.org/stable/60245672

- ↑ http://www.nlc-bnc.ca/collectionsp-bin/colldisp/1=0/c=88/

- ↑ “Courtland Benson Bookbinder Victoria, British Columbia Canada” http://www.bjarnetokerud.com/2010/03/blog-post.html

- ↑ Roberts, Matt. Bookbinding And the Conservation of Books: a Dictionary of Descriptive Terminology.

- ↑ Roberts, Matt. Bookbinding And the Conservation of Books: a Dictionary of Descriptive Terminology. p. 124

- ↑ Roberts, Matt. Bookbinding And the Conservation of Books: a Dictionary of Descriptive Terminology. p. 105.

- ↑ Roberts, Matt. Bookbinding And the Conservation of Books: a Dictionary of Descriptive Terminology. p. 105.

- ↑ Roberts, Matt. Bookbinding And the Conservation of Books: a Dictionary of Descriptive Terminology. Washington: Library of Congress , 1982. p. 132. See also http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_tissue

- ↑ Roberts, Matt. Bookbinding And the Conservation of Books: a Dictionary of Descriptive Terminology. p. 265.

- ↑ Bookbinding And the Conservation of Books: a Dictionary of Descriptive Terminology. p. 213.

- ↑ Bookbinding And the Conservation of Books: a Dictionary of Descriptive Terminology. p. 32.