Course:ENGL419/Books/BenJonsonMasques

Ben Jonson's Masques

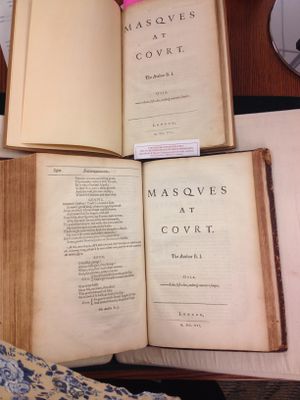

Originally printed in his first folio of 1616 by William Stansby, the collection of Masques written by Ben Jonson would have appeared at the end of the folio, after the plays and poems. However, this is not the case for UBC's copy in Rare Books and Special Collections. Instead, the Masques have been rebound separately from the rest of the collected works for reasons unknown to this amateur investigator. What is perhaps most interesting about this object is not the fact that it has been consciously separated from the first folio and bound in its own right, but rather the fact that at some point someone took the time to meticulously repair the ripped pages at the end of the text.

RBSC's copy of Masques is distinct from their copy of The Workes of Benjamin Jonson (1616) -- they were obtained from different donors and therefore the cause of the Masques separation from the rest of the first folio is indeterminate. However, this allows for a direct comparison of the ripped pages in Masques to the original pages in the copy of The Workes of Benjamin Jonson. Both were printed in 1616, with identical title pages for the Masques-- each section in the first folio had it's own title page. This is interesting because it allows the Masques to operate as their own text in some sense, despite being originally linked to the complete works.

Physical Description

While the complete first folio copy has what is likely it's original binding, the Masques have been rebound-- fairly recently by the looks of it. The inside back cover has a sticker stating "Bookbinding by Fritz Brunn: Victoria, B.C." The spine features gold detailing and lettering that indicates the content of the text: "Masques at Court" with the year 1616 at the bottom. Clearly, someone made efforts to maintain the authentic exterior of the text.

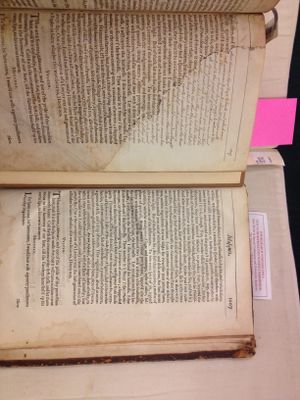

The paper in both texts is in very similar condition, although the Masques' pages are slightly yellowed. The Masques are not missing any pages in number, although several original have been ripped and/or removed and later repaired.

Typefaces

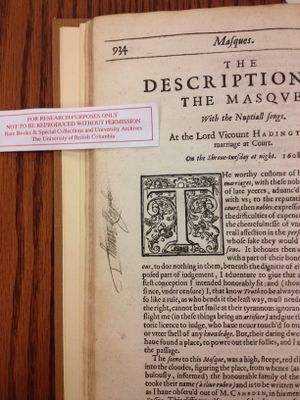

The typefaces used in both texts are identical, indicating that the Masques were originally a part of a copy of the complete Workes of Benjamin Jonson. Throughout, different sizes, features, and typefaces are used to signal headings, marginalia, character names, etc. Specifically, larger Italicized fonts are used for page headings and sub headings, whereas smaller italics are used for emphasis as well as for foreign or unusual words. Still smaller italics are used for notes/directions along the margins, in particular for the plays. Otherwise, small fonts along the margins in the Masques are used for notes and/or explanations . Capitalization of an entire word indicates character names and speakers (including the anthropomorphization of themes such as Truth and Opinion). The default or generic typeface used for the rest of the text is again identical between the Workes of Benjamin Jonson and Masques. Of interest, there is a greek typeface used on page 894 (and perhaps elsewhere). To me, this shows a concern for the readability of a text with a type of content that is generally observed, and not read. In fact, the entire collection of Masques with its extensive marginal annotations and explanations shows a general concern about presentation and readability.

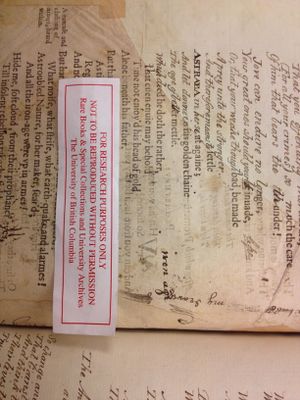

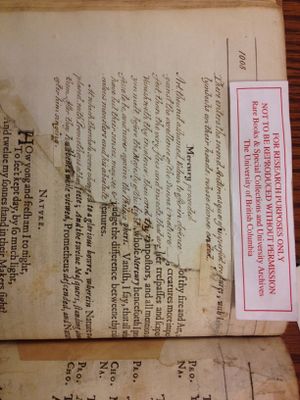

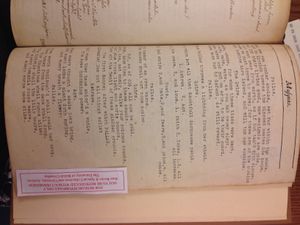

Of course, those pages that have been ripped or completely removed and replaced do not share the same typeface because the repairs have been made either by hand or by typewriter. The transgression from early print, to handwritten script, to typewritten text is compelling to consider. In particular, the typewritten pages lack any of the original variation in typeface size and style. Conversely, the handwritten script does showcase some variation in sizing and capitalization, though it does not attempt to distinguish between italics and roman script.

Inauthentic Marginalia

Several instances of doodles and pen-and-ink marginalia were haphazardly recorded out of interest. For example, on page 934 there is a shaky handwritten signature. While there is virtually no handwritten marginalia in the RBSC copy of Ben Jonson's complete Workes, the copy of Masques contains several intriguing bits of handwritten script aside from the obvious attempts to repair ripped pages. Many of the doodles and handwritten blurbs are concentrated towards the final pages of the Masques. It was thought that this could suggest a disregard for the preservation of the text. Could this be the same owner who directly or indirectly damaged the text? Compellingly, some of the doodles do seem to resemble a youthful or inexperienced hand.

Print and Publishing

Ben Jonson's first folio was printed by printer and publisher William Stansby in 1616. William Stansby is most well known for the production of this particular text. It has been said that Ben Jonson selected Stansby to publish his Workes because of the quality of his work and his reputation (Wikipedia). Before the printing of the complete works, Stansby published Certayne Masques in 1615, also by Ben Jonson. Jonson took an active interest in managing the rights to his works which was not very common in the 1600s before the establishment of authorial rights and copyright (Bland 1998).

Ben Jonson was directly involved in the printing and publishing of his works, devoting much time to the editing process (Bland 1998). A quantity of proof-corrections, notes, and other revisions demonstrates the intimate interaction of Ben Jonson with his text and those responsible for bringing it into print. In fact, Ben Jonson apparently lived a few hundred yards from the printing house.

Ben Jonson was unusual, or at the very least pioneering in the sense that he viewed his literary work as his own intellectual property, and sought to generate an undoubtedly modern authorial identity (Donaldson 2013). For this reason he sought to control the dissemination and publication of his work to subsequently be able to control its readership and reception (Loewenstein 2002). In the case of his masques, printing a traditionally temporary text allowed Jonson to minimize and control variation (Loewenstein 2002). The thorough descriptions in small text along the margins are not expressly for those who may intend to reproduce his entertaining performances, but rather to clarify and delineate the purpose and intent of each scripted moment.

Hymenaei

Intriguingly, in the notes and descriptions of several of his Masques are references to the print and performative aspects of masques. Specifically, in the Preface to Hymenaei (performed and first printed in 1606) Jonson makes an analogy between the body as performance, and the text as soul (Donaldson 2013; Wikipedia).

So short-liv'd are the Bodies of all Things, in comparison of their Souls. And though Bodies oft-times have the ill luck to be sensually preferr'd, they find afterwards the good fortune (when Souls live) to be utterly forgotten. (Masques 911)

In this way, we see Jonson's self-consciousness about the significance of the text as representing the meaning of a work. Jonson's extensive revisions of his plays and masques for print are justified in this sense: he intended for these performances to be read to allow for both a deeper understanding of his literature and a greater sense of control as an author (Bland 1998).

For example, the following excerpt demonstrates Jonson's usage of parenthetical explanatory notes to clarify the meaning of the nuances of his performances:

Hereat, Reason, seated in the top of the Globe (as in the braine, or highest part of Man) (Masques 914)

Fixing the Text

The attempts made to complete or repair the text are distinct in their obvious efforts to recall the original typeface styles, pagination, and format of the text. Despite these grand efforts, the job done is not a professional one. A comparison between those charged with professionally restoring texts, and those amateurs who sought to complete texts for personal or nostalgic reasons reveals interesting differences in intent and modus operandi.

Professional Restoration

The 19th century saw an increasing interest in the resurrection of incomplete manuscripts or early print texts. Books with missing pages often had facsimiles of the original pages inserted to re-complete the text. Wealthy book collectors were dissatisfied with books bought in imperfect condition, and were therefore willing to pay for the restoration or re-authentification of their incunables and early print books (Takamiya). It is perhaps telling that most of these so-called facsimilists were anonymous; they might be supposed to have humble intentions in repairing damaged texts, or otherwise to have a lesser skill in restoration. There is only one 'fixer' who achieved a certain level of notoriety: John Harris. The phrase "facsimiles by Harris" is indicative not only of the quality of his replications of early print pages, but also of his singularity as a professional facsimilist.

John Harris, born in 1811 into an artistic family, developed into an artist himself before pursuing an interest in reproducing early print facsimiles and wood cuts (Takamiya). Harris went blind in 1857 and died in 1873.

It seems that Harris' work went beyond restoration, so that his productions of Caxton and other famous printers became more desireable than the original texts themselves, thus transcending the line between authenticity and artistry. It has been said that his work is so precise that it may be difficult to distinguish between the original leaves, and the facsimiles (Takamiya).

Amateur Restoration

The anonymous facsimilists who make up the majority of such vary widely from those able to reproduce precise pen-and-ink facsimiles, to those amateur restorers who neatly repaired their own books for purposes of enjoyment and satisfaction. The latter is most probably the case with RBSC's copy of Ben Jonson's Masques.

At some point in this particular item's codicological history, someone took the time to meticulously repair and complete the damaged and missing pages in a beautiful handwritten script. These repairs were done in ink, and strive to emulate the formatting, alignment, and general appearance of the other original leaves.

Throughout the repaired or re-inserted pages, typographical elements of the original leaves are conserved such as the s long, the fonts, and other nuances of lettering including the interchangeability of 'v' and 'u'. Moreover, the style of pagination and headings are maintained. The pages themselves are stitched together expertly, in some places overlaid with strips of paper of the same material to hold the segments.

Most enthralling is the apparent evolution from half-ripped leaves to whole page facsimiles to typewritten pages, whereby the lattermost conserve virtually nothing about the typeface and headings of the original leaves. This evolution in remediation is analogous in some sense to the modernization in thought of the relative significance of typeface in considering a text accurate or authentic. In other words, to what degree is a paperback edition of Macbeth a true rendition of Shakespeare? How does the assembly of a Norton Anthology affect the meaning or readership of the texts contain within?

The jarring contrast between the original leaves and the beautiful handwritten script, and even further between the former and the typewritten pages is an experiment in the effect of typeface. Since first laying eyes on these three different versions, so to speak, of Ben Jonson I have wondered at the decision to abandon the hand written script for the typewriter. The typewriter would certainly be faster. Additionally, I have considered the possibility that the typewritten pages were perhaps placeholders for a later restorative effort. Another possibility is that the typewritten pages were inserted by another owner or restorer. Knowing more about the style and function of typewriters at different points in history might give an indication of when these repairs were done -- this example of typewritten script seems particularly neat and of good quality.

Short of identifying the ownership of the book during its restoration, we may never know. Either way, there was clearly a decision made about the degree of faithful conservation: a shift from preserving the style and appearance of the original pages (true facsimiles) to a preservation of the words and basic format (content facsimiles).

Masques

Fundamentally, the masque was a form of courtly entertainment popular in the 16th-17th centuries. Music, dancing, singing, and acting were all involved at various levels, bolstered by the ostentatious set designs, costumes, and number of performers. The performances were often allegorical or historically relevant (Wikipedia). Performers were a mixture of professionals (actors and singers) and courtiers (from Henry VIII to ladies of the court).

Ben Jonson's masques were famous for being similarly elaborate both in performance and metaphorical significance. The famous set architect and costume designer Inigo Jones collaborated with Jonson on multiple occasions. Jonson is one of the only writers of masques to have his masques printed (multiple times), and is even more atypical for his efforts to sequester the rights to these masques for bargaining and control purposes (Bland 1998).

Works Cited

1. "Hymenaei." Wikipedia. 15 Mar. 2014. Web. 20 Mar. 2015. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hymenaei>.

2. "Masque." Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 14 Mar. 2015. Web. 1 Apr. 2015. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Masque>.

3. "William Stansby." Wikipedia. 30 Nov. 2014. Web. 1 Mar. 2015. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Stansby>.

4. Bland, Mark. "William Stansby." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford UP. Web. 23 Apr. 2015. <http://www.oxforddnb.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/view/article/64163>.

5. Donaldson, Ian. "Jonson, Benjamin." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford UP, 1 Sept. 2013. Web. 10 Apr. 2015. <http://www.oxforddnb.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/view/article/15116?docPos=1>.

6. Jonson, Ben. The Workes of Ben Jonson. London: William Stansby, 1616. Print. Bland, Mark. "William Stansby and the Production of The Workes of Beniamin Jonson," 1615-16." The Library 20.1 (1998). Academia. Oxford University Press. Web. 15 Mar. 2015. <http://www.academia.edu/4064302/William_Stansby_and_the_Production_of_The_Workes_of_Beniamin_Jonson_1615-16>.

7. Leed, Drea. "Examples of Masque Costume in the Late 16th & Early 17th Centuries." Elizabethan Costume Page. Web. 7 Apr. 2015. <http://elizabethancostume.net/masque/index.html>.

8. Loewenstein, Joseph. Ben Jonson and Possessive Authorship. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UP, 2002. 167-9. Web.

9. Takamiya, Toshiyuki "2. John Harris and the Facsimile Pages." British Library Treasures in Full: Caxton's Chaucer. British Library. Web. 3 Apr. 2015. <http://www.bl.uk/treasures/caxton/johnharris.html>.