Course:ENGL419/Books/Babylonian Cuneiform Tablets

UBC's RBSC library has a collection of Babylonian Cuneiform (Koo-NEIGH-uh-form) tablets. There was originally six tablets in the collection, however one is unfortunately missing. The tablets were found at Ur in Chaldea during an excavation done by Yale University in the early 1900's. The excavation was conducted by Professor Albert Tobias Clay. Each tablet is inscribed on both sides and is either a square or a rectangle. The tablets were from the third dynasty of Ur from the Babylonian Empire. Ur is a city in the region of Sumer, which is located at the South end of Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq).

Tablets A, B, C and F

Tablets A, B, C and F are from the reign of Shulgi (originally known as Dungi). They record a receipt of the rent given to the temple authorities.

Shulgi

Shulgi was formally thought to be Dungi. There was some confusion over the pronunciation of the first symbol. The reign of Shulgi was from 2456 B.C. to 2398 B.C. He was the second king of the third dynasty of of Ur. The first king was his father, Ur-Nommu.[1] During his reign, he revised the scribal schools and raised literary rates across the region.[2] In order to separate his reign from his father's and establish himself, he ran from Nippur to Ur and back (200 miles) in a day.[3] He was thought to be one of the greatest kings of the third dynasty of Ur.

Tablet A

Tablet A is a small sized square. It has an orange and brown colour to it. There appears to be little blue specks scattered along the bottom left corner on one side. The symbols on the tablet are written in horizontal lines and appear on the top, the bottom, the right side, the front and the back. The left side is blank. There are six rows of horizontal lines on the front and back and the markings are engraved or pressed into the tablet.

Tablet B

Tablet B is a larger square. It is black on the edges, fading slightly to grey as you near the center. The other side is black along the right edge and a mix of light brown and grey on the bottom left. The center of this side appears to be missing. The markings are cut off in this section and they continue on either side of the center. The center also has a rougher texture compared to the rest of the tablets. The markings at the top are engraved or pressed into the tablet. The markings in the box at the bottom of the tablet are like indents. You can feel them as you run your hand along the surface.

Tablet C

Tablet C is a medium sized rectangle. The colour is a mix of yellow, orange and tan. The tablet also has black spots and orange streaks scattered about. On one side, there are vertical columns on the left and right. The center is blank. When we flip the tablet over, there appears to be a chunk missing on the top left corner. We can assume that the tablet was written before the rest because of the vertical columns. However, the tablet could also just be sideways.

Tablet F

Tablet F is the sixth tablet in the collection and is missing. It was stolen off its display case about 19 years ago, during an open house. The tablet was made during the 45th year of Shulgi's reign and is 1 3/4 inches by 1 1/2 inches in size. It is a note on workman for agricultural work.

Tablets D and E

Tablets D and F are from the reign of Bur-Sin (also known as Amar-Sin). They record a receipt of rent paid to the temple.

Bur-Sin

Bur-Sin was also known as Amar-Sin.[4] He was the son of Shulgi and the third king of the third dynasty of Ur. There was great prosperity and much construction during his reign. Unfortunately, his reign only last for eight year (2398 B.C. to 2390 B.C.) as he died of a foot infection. He was succeeded by his brother.

Tablet D

Tablet D is a medium sized square. It has a white gray colour to it. The markings are indents and appear to be darker in colour than the tablet. There are markings on all sides (top, bottom, front, back and right side) except the left. There are two holes on the tablet. These could be from stones or plant material left in the clay.

Tablet E

Tablet E is a small square. It is brown in colour with splashes of yellow in the markings and black at the bottom. There are five horizontal rows on each side and the writing goes through the right. There is no writing on the top, the bottom or on the left side. Tablet E has King Bur-Sin's name written on it along with the year Huhnuri was destroyed. It is a receipt for one sheep and one lamb.

Cuneiform

Cuneiform comes from the Latin "cuneus" meaning wedge. This is because of the wedge shaped marks the stylus made in the clay. The stylus, which was usually made from reed, made a triangular impression in the clay that represented word signs or pictographs and word concepts or phonograms.[5] Originally, cuneiform was written in vertical lines. This was later changed to horizontal. When scribes wrote on the tablets, they would use every surface, allowing them to copy large amounts of text. For longer text, they would use multiple tablets and connect them with numbers or catch words. To see your name in cuneiform click here

History

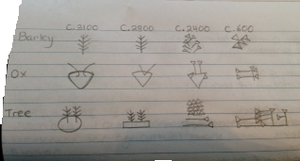

Cuneiform was developed in the lower Tigris and Euphrates valley [6] by the Sumerians of Mesopotamia. It was developed because temple officials were looking for a way to keep track of the products (such as animals) that entered and left their supplies.[7] The earliest form was proto-cuneiform.[8] This was characterized by pictures of items or pictographs being pressed into clay with a stylus (sharp tool). Objects or ideas in proto-cuneiform were more concrete. Proto-cuneiform later gave way to cuneiform as it was becoming apparent that some object were hard to depict. It was easier to use representations for objects rather than drawing the actual thing.[9] A wedge shaped stylus was used to make triangular marks in clay. The symbols were less complex in cuneiform. The triangular symbols represented word concepts rather than word signs ('Honor' instead of 'the honorable man').[10] Cuneiform was replaced by Rebus, in which signs could mean either the intended meaning or sounds/sound groups.[11] An example of this is a picture of an eye meaning either 'eye' or 'I'. Rebus started being used in 3200 B.C. but was mostly used after 2600 B.C. It was later replaced by the alphabet.[12]

Formation of Clay Tablets

The clay used to make tablets came from sediment, which could be found in riverbanks.[13]Once the clay was collected, it was levigated in order to remove inclusions, which would make it hard to write.[14] When clay was levigated, it was mixed with water and left to stand. In this process, the coarser materials in the clay would sink to bottom and the plant materials floated to the top. The material at the top would then be removed. Plant material that wasn't removed would leave holes in the clay.[15] The clay that was found in the middle is what as used to make the tablets. Once levigated, the clay would be kneaded, mixing the wet clay with the dry clay. Kneading also removed air bubbles. After the clay was kneaded, it was shaped by hand molding pieces of clay or by using the envelope method. In this method, pieces of clay were folded over each other and water was used to put them together.[16] Some tablets also had slips on the surface to make them look nicer. Slips were made from diluted clay that was applied to the surface of a tablet.[17] While the clay was wet, scribed would use a stylus to write on the clay. The clay would then be baked in the sun. To make your own cuneiform tablet click here

References

- ↑ Mark, Joshua J. Shulgi of Ur. "Ancient History Encyclopedia". 17 June 2014. Web. http://www.ancient.eu/Shulgi_of_Ur/l

- ↑ Mark, Joshua J. Shulgi of Ur. "Ancient History Encyclopedia". 17 June 2014. Web. http://www.ancient.eu/Shulgi_of_Ur/l

- ↑ Mark, Joshua J. Shulgi of Ur. "Ancient History Encyclopedia". 17 June 2014. Web. http://www.ancient.eu/Shulgi_of_Ur/l

- ↑ Amin, Osama S.M.. Mud-Brick of Amar-Sin. "Ancient History Encyclopedia". 10 April 2015. Web. http://www.ancient.eu/image/3779/

- ↑ Mark, Joshua J. Cuneiform. "Ancient History Encyclopedia". 28 April 2011. Web. http://www.ancient.eu/cuneiform/

- ↑ Duschens, "Philips C. Medieval Miniatures and illuminations". New York, New York. Print.

- ↑ Historic Writing. "The British Museum". Web. http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/themes/writing/historic_writing.aspx

- ↑ Mark, Joshua J. Cuneiform. "Ancient History Encyclopedia". 28 April 2011. Web. http://www.ancient.eu/cuneiform/

- ↑ Historic Writing. "The British Museum". Web. http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/themes/writing/historic_writing.aspx

- ↑ Mark, Joshua J. Cuneiform. "Ancient History Encyclopedia". 28 April 2011. Web. http://www.ancient.eu/cuneiform/

- ↑ The Origins of Writing. "The Metropolitan Museum of Art". Web. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/wrtg/hd_wrtg.htm

- ↑ The Origins of Writing. "The Metropolitan Museum of Art". Web. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/wrtg/hd_wrtg.htm

- ↑ Taylor, Johnathan. The Making and Re-making of Clay Tablets. "academia.edu". 2011. Web. http://www.academia.edu/2225793/The_making_and_re-making_of_clay_tablets

- ↑ Taylor, Johnathan. The Making and Re-making of Clay Tablets. "academia.edu". 2011. Web. http://www.academia.edu/2225793/The_making_and_re-making_of_clay_tablets

- ↑ Taylor, Johnathan. The Making and Re-making of Clay Tablets. "academia.edu". 2011. Web. http://www.academia.edu/2225793/The_making_and_re-making_of_clay_tablets

- ↑ Taylor, Johnathan. The Making and Re-making of Clay Tablets. "academia.edu". 2011. Web. http://www.academia.edu/2225793/The_making_and_re-making_of_clay_tablets

- ↑ Taylor, Johnathan. The Making and Re-making of Clay Tablets. "academia.edu". 2011. Web. http://www.academia.edu/2225793/The_making_and_re-making_of_clay_tablets