Course:ECON371/UBCO2010WT1/GROUP5/Article 7

Back to:

Ecotourism Brings Home the Bacon in the Peruvian Amazon

Summary

The article details that in the Peruvian southern region of Tambopata, there has been a positive economic influx from eco-tourism, as an alternative for employing the land for cattle-ranching and logging purposes. A study conducted for the journal PLoS ONE. The study considers the effect of a piece of legislature that was effected in 2002 by the Peruvian government which enables the usage of the region for tourism purposes, in the hopes of encouraging the preservation of the area as part of the tourist attraction.

Some critics of the movement were hesitant about eco-tourism's effectivity in comparison to other (more destructive) activities, according to the article, which prompted the authors of the study to calculate revenues for the different usages of land and comparing them. The report found that eco-tourism was second only to "non-sustainable timber harvesting." Eco-tourism is economically tractable, according to one of the authors of the study, Douglas Yu of the University of East Anglia. Even ignoring the benefits of carbon sequestration and the preservation of biodiversity, maintaining the Tambopata region as an eco-tourist zone makes sense, as it does garner some revenue, and can be linked to other tourist activities such as the Inca Trail in the neighbouring city of Cusco. This creates an attractive portfolio of activities that exploit the land without really damaging it.

Yu did warn that the eco-tourist places have to be sensibly placed– anything near a coral reef is bound to create more damage than it abates. The authors of the study believe that it is one of the first studies to analyse the profitability of tourism as an incentive to protect regional biodiversity, and to compare the economic gains from this activity in comparison to less sustainable ones such as logging.

[Photo by Chris Kirkby]

[Photo by Chris Kirkby]

Analysis

The article makes reference to a method for assessing costs and benefits for particular activities, specific to regions. In this case, assessing the market value of the Amazon rainforest has been done by employing a combination of direct and indirect method approaches. Actual revenues for eco-tourism are taken into consideration, as well as the surrogate market approach, where an area is worth at least however much individuals are willing to pay to visit it. Aggregating this to the previous method derives a demand curve that can be readily compared to demand curves of other activities that employ the same amount of land- like ranching, logging, or planting soy beans for biofuel.

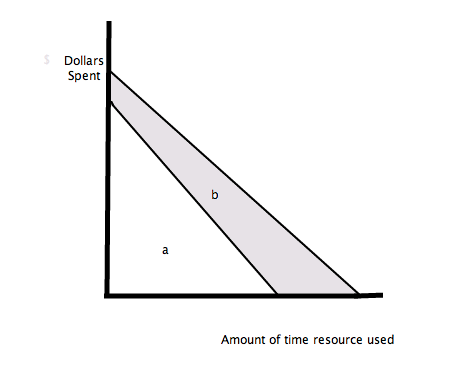

The study points to the effectiveness of eco-tourism in the region as the source of income. it indicates that, after harvesting for logging, eco-tourism garners the most profit in terms of efficiency and gross revenue. If these were the only two factors, it would seem that the socially efficient activity would be to engage in logging- even if the costs incurred are high. However, the study is not blind to the benefits accrued by the tourism approach. Aside from the revenue that is is capable of generating (by the tourists flocking into the region and using the resources) there are some added benefits to the practise. These include services by the region, not exploited for their minerals of trees, such as carbon sequestration and the preservation of biodiversity. If these things are given a market value (proportional to the travel costs that people are willing to incur for visiting the region, as well as decreases in abatement costs) a nice demand curve can be generated and compared to other activities that would be substitutes to eco-tourism. In other words, the study assesses not only the direct economic impacts of eco-tourism, but also takes into consideration the positive externalities that the activity generates. A set of demand curves- or better put, willingness to pay, with the added externalities in the light pink region, is shown below.

This is, of course, an over-simplified model, but it does not mean that the model is not effective at describing the industry's gains. In an intertemporal setting, where future gains are discounted and some externalities are made evident, the situation would still hold. Presuming that the goal is to both incur some revenue from the practises of exploiting the Amazon region and, at the same time, preserving the rainforest (or we can think of the situation as decreasing depreciation across the entire Amazon) this alternative does seem tractable. It is region-sensitive, just as geothermal energy exploitation is, but it does preserve the land and is growing more as a credible and viable alternative to logging the Amazon flat. Governments can further this commitment to the environment by making the activity seem attractive to investors and to tourists. A multitude of tools are in their service: they can insert some sort of tax break for firms willing to invest in eco-tourism and land preservation- such as regional travel agencies that make the land available for eco-tourism. Governments can declare certain areas as eco-tourist areas only, and/or make it really expensive for other activities to take place by heavily taxing other practises. The tax level would be set at least where marginal abatement costs (for society) would equal marginal damages. The last approach is a very centralised method of inducing policy, but it would probably work best (granted that the government is not in shambles and is actually able to enforce the policy.) By declaring a region as designed only for eco-tourism, the areas are preserved and there is less depreciation of the capital stock- The Amazon in our case- at extremely low emission levels.

Conclusion

This is one of the rare cases where using surrogate markets is actually relatively easy for assessing market values of abstract assets, such as the rainforest. The study presents us with a positive picture of eco-tourism, which allows for some relatively straightforward assessment of revenues at low costs. In addition, the externalities (granted, hard to measure) seem to be mostly on the positive side, and increase the market value of the asset. Taking into consideration that eco-tourism is region-sensitive, governments should look into this alternative, as the study does present a good case for it in comparison to other activities which generate a lot more emissions and degenerate the rainforest. A centralised approach of altogether banning the active exploitation of the rainforest in these tourist-worthy areas would help achieve more efficiently a social equilibrium of costs and benefits, while at the same time show some serious commitment with the environment.

Prof's Comments

Ecotourism is next to logging in terms of profitability. Absent a policy to support ecotourism, which activity will dominate? It seems ecotourism varies as well by location, as more remote areas don't get as much ecotourism. What would the efficient mix be? Is there any interaction between ecotourism and forestry?