Course:ECON371/UBCO2010WT1/GROUP5/Article 6

Back to:

Amazon Rainforest Will Bear Cost of Biofuel Policies in Brazil

Summary

The article discusses the biofuel expansion targets for 2020 and the negative impacts this will ensue for Brazil’s Amazon rainforest. The recent paper, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), suggests that the costs of the transition from fossil fuels to biofuels undermines the emissions savings of the conversion altogether. David M. Lapola of the University of Kassel (Germany), found that the change to biofuel although directly requires little land, it will generate a huge indirect impact on large areas of the rainforest. Lapola suggests this will occur through displacement of cattle ranching, the current dominant land use, pushing rangeland to expand by an estimated 167,970 sq km into the frontier of the forested areas and other native habitats.

The findings propose the integration of Soy biodiesel as a biofuel, will incur a carbon payback time for direct impact emissions of 35 years, but when including the indirect impact emissions, the payback time leaps to 211 years.

The evidence in the article concludes that oil palm fulfils Brazils biofuel demands with much less land use and carbon debt than soy biodiesel and sugarcane ethanol. Lapola also suggests that reinstating the use of disposed rangelands instead of venturing into native lands would reduce the potential damage caused by the indirect emissions. To overcome these problems the article heavily suggests ‘an increased interconnection between land-use sectors’, ensuring cooperation’s between the two sides and guaranteeing that emissions are minimised.

Analysis

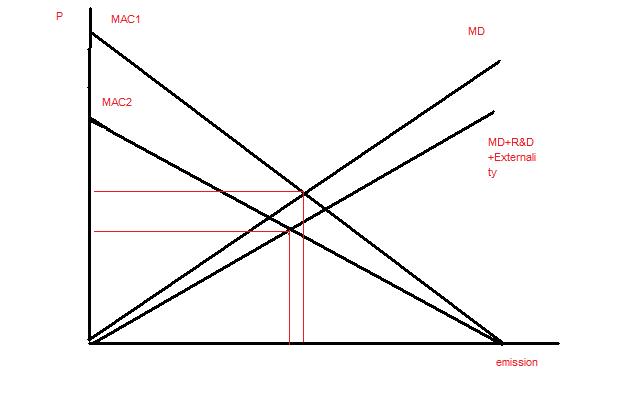

This article introduces some basic ideas of sustainable biofuels, but when an incorrect approach is used, R&D improvement may lead to a flawed result. Compared with fossil fuels, the new promotion in Brazil of using biofuel such as soybean and sugarcane can, at a first glance, reduce the green house gas emission. What's more, the new development of biofuel can lighten the reliance on fossil fuel energy,and it appears the carbon payback time for biofuels is far less that that of fossil fuels, 4 years for sugarcane and 35 years for soybean. However, when we think deeper into the indirect land use effect, the story changes dramatically. Due to the forced expansion of biofuel cropland and rangeland, a large area of forest is destroyed. Referring to the graph, one can see that the shift of the Marginal Damages Curve, even taking into consideration the reduced effect of innovation of technology, actually decreases the amount of emissions reduced at the equilibrium point, under the Marginal Cost Curve 1. This is actually an ambiguous movement, as we have no reason to believe that the Marginal Cost Curve stays the same (innovation would likely make the abatement costs slightly cheaper.) For simplicity, the change is deemed negligible, and the levels stay the same. Adopting the Soy Bean Biofuel, once externalities (such as direct deforestation) are considered, turns out to be more damaging in comparison to other alternatives. In other words, adopting that technology causes further deforestation.

In the article, David M. Lapola from the University of Kassel offers an alternative solution for this. He suggests that planting oil palm instead of soybean for stockfeed for the biofuel quota. Although planting oil palm incurs a higher level of direct deforestation,its high yield per square kilometre as well as the carbon payback time, in the long run oil palm, actually incurs in a less severe tree loss than using soybean cultivates. It is more effective at meeting the quota, as evidenced by the graph. The new Marginal Cost Curve, #2, corresponds to the adoption of this technology. For simplicity, the new MD curve will be the same as the curve for Soybean (though it admittedly is not the same, for the tree loss is not equivalent.) The MAC curve is where it is, on the basis of a much diminished Carbon Payback time in comparison to the Soybean MAC. One can see that under this technology, emission decrease (in the form of less trees being felled) is actually greater under equilibrium.

Conclusion

If the information reported on the article is to be believed, oil palm is undoubtedly the better alternative. One possible way for the government of Brazil to go along this line of thought is to apply a system of transferable discharge permit, or possibly tax incentives on select technologies on the different biofuel producers. Under this policy, producers that are using the land use would have a strong incentive to innovate, by planting the high-yield oil palm.

Prof's Comments

Your final comment about tradable permits should be explained. What would the permit be for? Is this perhaps a situation where taxes and subsidies for particular activities may be a more effective approach?