Course:ECON371/UBCO2010WT1/GROUP5/Article 3

Back to:

Legal Opinion: Brazil's Amazon Tribes Own Carbon Trading Rights

Summary

The article discusses the legality of carbon trading rights in reference to the Brazilian Amazon tribes. It refers to the findings of the international law firm Baker & McKenzie, commissioned by Forest Trends, which were presented at Copenhagen on 2009 (ENS). After years of eroded rights by the numerous international agreements on climate change, the indigenous groups of the Brazilian Amazon have ‘the right to the carbon in their standing forests’. This inference is based on the actual Brazilian Constitution and legislation, which "reserves to the Brazilian Indians.. the exclusive use and sustainable administration of the demarcated lands as well as the economic benefits that this sustainable use can generate."

This finding was thought to not only prevent deforestation, in turn maintaining one of the world’s critical carbon reservoirs, but also to promote the rights of the indigenous people and safeguard the existence of the Surui tribe population, which has dropped from nearing 5,000 to 1,200 members.

However, during the Copenhagen climate summit, the REDD (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation) text removed several numeric targets for reducing current deforestation levels and weakened safeguard language by moving it from operational text into the preamble to the REDD section. This, as stated by Alistair Graham of Humane Society International, “weakens the agreement and deprives it of any assurance of compliance".

All in all, suggesting that although there is a general agreement that the world’s rainforests require protection, there seems to be very little action upon doing so.

Analysis

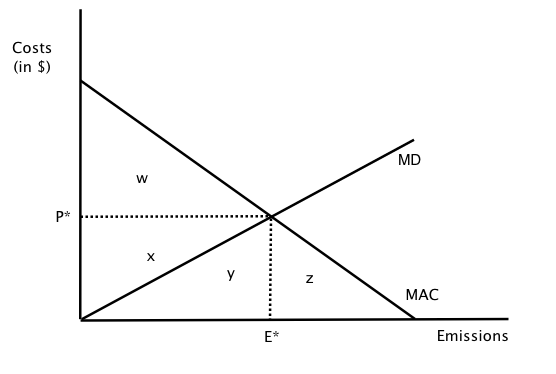

This article has liability issues at the heart of the issue. The Native Surui population have the intent of seizing their property rights in relation to the emission of carbon in their government-assigned territory, which amount to a sizeable 600,000 acres, and turning a profit. The issue has many faces. On one hand, it finally recognises that the lands are actually the property of the native populations, who are responsible for their keeping and rightfully deserve to reap the benefits of its exploitation, to whichever degree. For the sake of comparison, let us assume that the collection of firms interested in purchasing carbon rights from the Surui are represented by a single firm, and that the entire carbon rights belong solely to the Surui. Holding externalities at zero (assuming everyone knows everything that is going to happen in the world at period t.) Suppose, finally, that the firm is to compensate the Surui at the level of abatement cost for total carbon emissions per month. Refer to the diagram below:

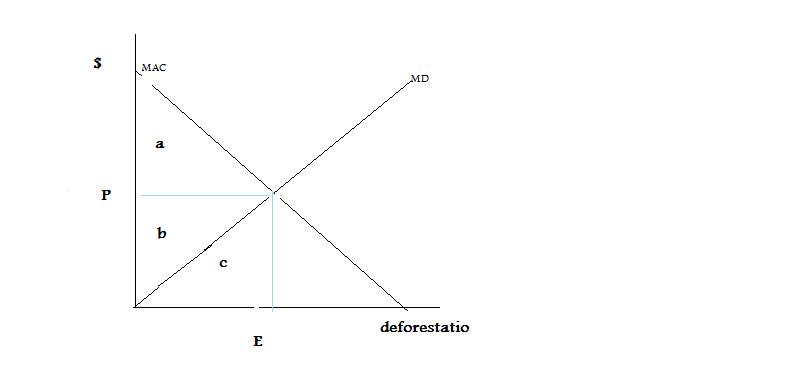

The Surui would accept a level of emissions of carbon equal to the equilibrium emissions, E*, and be recompensed at a price of P* at that level. The firm would accept this level of emissions, if it were seeking to minimise costs, as any more emissions beyond E* that would not interest the Surui, and any emissions beneath E*'s level would incur a higher cost than a benefit. The net benefit the firm would incur would be the area denoted by a, which corresponds to the monetary value that the firm accrues for activity at that level of pollution. It does not incur the whole benefit, as it must recompense the Surui areas b and c- the damages and property rights that belong to them. Likewise, the Surui would accrue a net benefit b, as they sustain damages equal to the area c, and are recompensed a total of area b+c. Illustrated in pretty colours, in terms of deforestation, is the diagram below:

As we can see, the total amount paid by the firms, b+c, is always bigger than the total damage c caused. Deforestation in their acres is reduced to a socailly efficient level. At this level, it might even be the case that the practise is sustainable due to trees' reproduction. This social efficient level can also be achieved by letting firms purchase the rights to emit carbon- indigeous people are not paying for the destruction of the rainforest but the firms are. This is more ethical in this particular case, since the indigeous people may not have the money to pay the cost and drive to the efficient point.

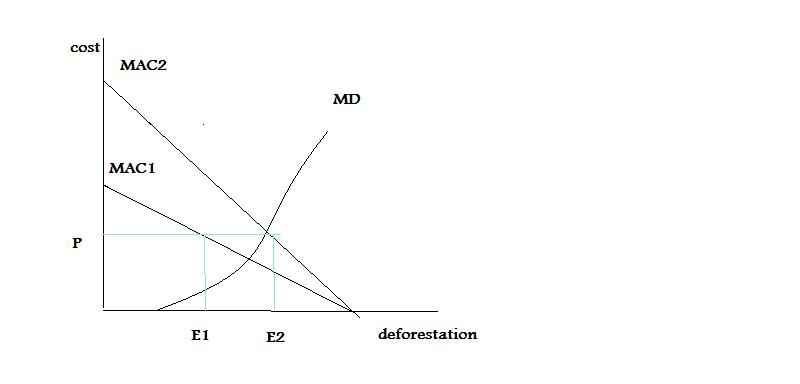

This is a highly idealised case. In reality, externalities are not truly ever known or inexistent- in particular with pollution and large portions of the land. Moreover, it is often the case that the amount firms pay for carbon emission rights undermine the true costs of deforestation, which are long termed and usually overreaching in their effects. In addition to the uncertainty associated with any policy, the framework wherein the natives' rights are enforced is being weakened by the very organisations who sought to institute the protection of the rainforest— namely, the REDD text during the last climate meeting. This means that enforcing the natives' rights to their property becomes more difficult, and the real cost curve would most likely alter slope and be located in an outward shift of the MAC.

In the article, previous emission standard is erased from the REDD text which causes concern about the power of it. The social efficient standard graph should look like this:

there should be a threshold since a proper amount of logging would do no harm to our environment. When comes to a certain amount it would goes up with a flatter slope,and when it goes up higher meaning the deforestation speed is over the recovery speed that the rainforest can take, the MD rises steeper. It's also important for REDD to come with a total deforestation target. Because different firms have identical MAC curves, we can apply the equimarginal principle here by equalizing the marginal abatement cost therefore minimizing the total deforestation amount. Without setting a total target, firms may have the incentives to cut more trees.

Conclusion

It is a recurrent theme with environmental policy that things are not always what they seem. The issuing of property rights to the Amazon Surui tribe is certainly a step towards social equality and efficiency- recognised even in the geo-political legislature of the region. Despite this, as noted in earlier articles, the issuing of carbon rights and subsequent selling of them to firms for pollution rights—even at the socially-efficient level of emissions and recompense (unlikely on its own) does not constitute a sufficient, "radical" decrease in emissions, which is what the Amazon truly needs. It is a start towards social equity, though one salient with political setbacks from the start.

Prof's Comments

Nice work, attempting to squeeze this issue into the framework we have developed so far.

The clarification of property rights really enters into using some sort of trade to achieve efficiency, and the article talks about carbon trading. With the benefits accruing to the indigeneous peoples, then they have an extra incentive to protect the forest. Their traditional way of life may therefore enhance their financial welfare, rather than leaving them worse off.

In a couple of lectures, we will cover this issue in more depth.