Course:ECON371/UBCO2010WT1/GROUP2/Article7

Back to

Group 2: The Environmental Impacts of Natural Gas Extraction

Article 7: Study: Gas drillers to damage state's 'iconic forests'

Summary

Most of the news articles analyzed previously have been focused on the pollution of water or air from the process of natural gas drilling; however, this article looks at the biodiversity at the fracking sites. The non-profit organization Nature Conservancy stated that over the next twenty years, 35,000 to 95,000 acres of forest could be destroyed from meeting the demand for natural gas and other new energy developments. In Pennsylvania alone, natural gas producers are expected to eliminate 3.1 acres of trees per well pad, plus an additional 5.7 acres for access roads. An estimated 60,000 more wells will be drilled in the next 20 years. Considering the rate at which forests are being destroyed, the organization wants producers to protect habitats for birds and other wildlife animals. The state of Pennsylvania has some solutions for dealing with deforestation. It requires drillers to report which species would be potentially affected by the clearing of forests. In addition, some drilling companies share access routes with competition to reduce tree cutting for road construction, which accounts for almost two thirds of forests cleared by natural gas industry. Natural gas pooling is also becoming common. This allows drillers to extract gas under multiple properties from one well, redistributing the profits proportionally. The method of pooling reduces surface area disturbances, such as deforestation.

Analysis

Considering Pennsylvania has very high pollution, the loss of 3.1 acres of forest per well pad and an additional 5.7 acres for access roads and pipelines will contribute significantly to an increase in the levels of carbon dioxide with the addition of more effluent-producing wells. Allowing natural gas companies to clear-cut forests is also detrimental to the Pennsylvanian forestry industry, which contributes roughly $6 billion ([1]). Excessive clear-cutting would reflect negatively on the regeneration process for forests. Furthermore, tourism would likely reduce if the natural environment lost its “iconic” forests.Some of Pennsylvania’s prime natural gas drilling zones happen to lie under the state’s deep forests, which are the habitat of many birds and other wildlife. As the industry continues to grow, the issue of habitat protection is becoming increasingly important. The Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources conducted an investigation of the impacts of additional natural gas development on forest lands, the results of which can be viewed at their website. ([2]) They have concluded that additional leasing of forest lands for natural gas extractions would destroy the majority of ecologically sensitive areas, which are home to many species of plants and animals, provide wildlife travel corridors, and have a scenic or aesthetic value. In their mapping analysis they argue that no more forest land should be leased for natural gas development. While it is true that large habitats may be destroyed by natural gas extraction, from an economic standpoint it is important to evaluate the costs and benefits of forest protection in monetary terms. Since no market exists for species diversity, evaluating the benefits of habitat preservation is not as straight-forward as evaluating its costs, which can be deduced from lost sales of natural gas.

Regulators have several options for deducing an estimate of people’s willingness to pay for biodiversity. These include the travel-cost approach, hedonic estimation, and contingent valuation. In the travel-cost approach, regulators would deduce people’s willingness to pay for biodiversity from the amounts they pay to visit Pennsylvania’s forests. For example, they could consider prices at nearby recreational resorts, as well as travel costs of visitors from other regions. However, if a particular visitor is making a trip to Pennsylvania’s forest for reasons other than admiring biodiversity and scenery, then the amount he paid for the trip will not accurately reflect his willingness to pay for species protection. In hedonic estimation, regulators would look at prices of houses near the forests in question, and break these down into components to determine people’s willingness to pay for forest preservation. The problem with this method lies in the fact that the greatest variety of wildlife is generally found deep in the forest, removed from human activities and housing. Contingent valuation, in which regulators ask people for their willingness to pay, may seem like the easiest method to use. However, its hypothetical character may lead to people expressing a very high willingness to pay for preserving biodiversity, even if they do not enjoy it directly, simply because of its existence value.

The costs of habitat preservation can be determined from people’s demand for natural gas. If people’s demand for gas is high, they will likely accept some damage to forests in order to maintain a supply of natural gas. Their demand for gas will be reflected in gas prices. In the end, regulators can compare demand for biodiversity preservation with demand for natural gas to arrive at an efficient equilibrium at which no person can be made better off without making somebody else worse off.

The benefit-cost analysis of preserving forests and biodiversity is further complicated by the local nature of the issue. People in Pennsylvania may care strongly about preserving their forests; however, somebody living in another part of USA may be more concerned with low prices of natural gas. To this person, the benefits of natural gas extraction will far exceed the benefits of habitat protection, while the opposite is likely to be true for a Pennsylvanian. If a decision about further development on Pennsylvanian forest lands is to be made at the state level, the impact on habitat will likely be incorporated into the benefit-cost analysis.

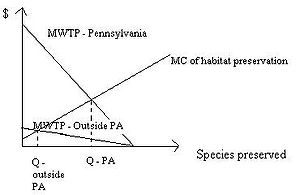

Figure 1 demonstrates how the equilibrium between benefits and costs of habitat

preservation would change if a decision about further natural gas development on Pennsylvania forest lands was made at the federal or the state level. Assuming that demand for natural gas is uniform throughout USA, all regions would suffer equally if natural gas production was reduced in an attempt to preserve forests and biodiversity. Thus, the marginal cost curve will be the same for a person in Pennsylvania as for a person in any other state. However, a person living far away from Pennsylvania’s forests may not receive much benefit from preserving its biodiversity, and therefore their benefit curve will be much lower than that for a Pennsylvanian, who enjoys walks in the to-be-affected forests for their aesthetic values and biodiversity. As such, the federal level, which will consider the opinions of all Americans, will preserve fewer species and fewer habitats than the Pennsylvanian state government, which will consider primarily the local opinions.

As a result, the federal government has very little incentive to enact regulation which aims to protect biodiversity in Pennsylvania. Such a move would likely cause the current government to lose the support of voters who are not interested in protecting biodiversity in another state in a forest which they never visit. Therefore, if wildlife is to be protected, the state government will have to enact regulation limiting new natural gas development in Pennsylvania. Issuing a certain amount of permits may be an efficient way to achieve this; however, it will likely have to be based on a zonal permit trading system, since certain areas will be more affected if higher species diversity is located in these areas. For example, a producer will have to hold a permit to build a well near the outskirts of a forest, but will require multiple permits to undertake production in the more sensitive areas deep in the forest.

Another way to limit the number of forests cleared is for the Pennsylvanian government to sign more executive orders that prevent certain natural gas development activities, which it has done recently. The natural gas extraction companies will be forced to adapt to a changing perspective in the Pennsylvanian resident base. There is an increasingly growing concern over the extraction methods used, that, tied into the possible loss of tens of thousands of acres of iconic forest, could cause great social unrest and force companies to subdue their drilling.

Prof's Comments

Some interesting stuff here. You have not dealt with existence value though. While people outside of PA may care less about the PA forests, in terms of their use of those forests, they may still have an existence value for it. Also, the benefit from lower natural gas prices is felt through the market price, and thus is easy to measure economically. From a political perspective though, you are right that people outside of PA may be less inclined to vote for measures that protect PA forests.